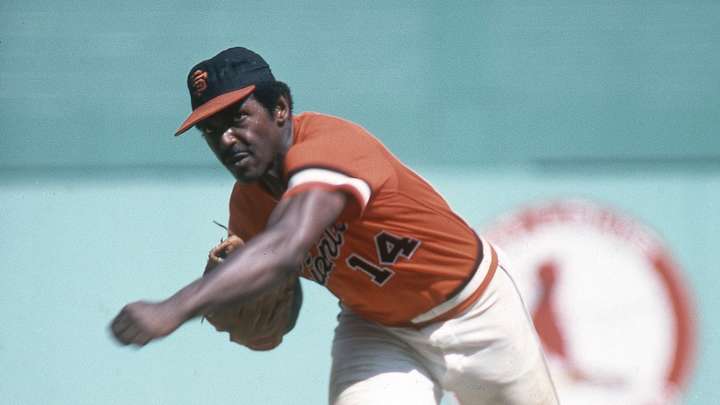

Former SF Giants LHP, Bay Area legend Vida Blue passes away at 73

Former SF Giants, Oakland Athletics, and Kansas City Royals starter Vida Blue passed away on Saturday night at the age of 73. A hard-throwing lefty at the peak of his career, Blue is one of the best pitchers in MLB history who has not been inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame. During his MLB career, which spanned from 1969-1986, Blue had a pair of stints with the Giants, reaching three All-Star games in his six seasons with the team.

“Vida Blue has been a Bay Area baseball icon for over 50 years,” said Giants president and CEO Larry Baer in a team press release. “His impact on the Bay Area transcends his 17 years on the diamond with the influence he’s had on our community. For many years, he was such an integral part of our Junior Giants program. Our heartfelt condolences go out to his family and friends during this time.”

Blue was drafted in the second round of the 1967 MLB Draft by the Kansas City Athletics out of his hometown of Mansfield, Louisiana. Despite his youth, Blue breezed through the minor leagues and made his big-league debut in 1969, just over a week before his 20th birthday.

In 1971, Blue's first full MLB season, the southpaw had one of the best seasons in league history. He finished the campaign 24-8 with a league-leading 1.82 ERA across 312 innings pitched with 301 strikeouts. He threw complete games in 24 of his 39 appearances, recording nine shutouts. Even by modern metrics like FIP and WAR, Blue was the best pitcher in the league that season. He won the Cy Young and Most Valuable Player awards.

During his MVP season, Blue's annual salary was so low that he qualified to live in West Oakland's publicly subsidized housing. So, on the heels of such a great season, Blue went to the negotiating table with then-A's owner Charlie Finley seeking a raise.

MLB was in the middle of a transformational period for player compensation. While players only signed one-year contracts with their teams each season, the reserve clause prevented them from negotiating with other organizations even after their deals expired. Outfielder Curt Flood became the first player to challenge the reserve clause in decades after refusing a trade to the Philadelphia Phillies in 1969. As Blue began negotiating with Finley, Flood's case was being heard by the Supreme Court.

Blue and his attorney were seeking a $92,500 salary, significantly less than the highest salary in the league (Carl Yastrzemski's $167,000). Still, Finley, a notoriously cheap owner, refused to meet Blue's incredibly reasonable demands. While Blue threatened to retire from baseball to pursue a career as a plumber, he ultimately settled for a $63,000 salary.

“It left a sour taste in my mouth, and who knows how that one year — and the incident itself — changed my attitude about my job and the game that I loved,” Blue told the Washington Post in a 2021 interview. “It created this issue with me that I never had let go of.”

While the Supreme Court ruled against Flood in a 6-3 decision, the labor movement among MLB players was gaining steam. In fact, for the first time in league history, MLB players went on a strike that led to the cancellation of games at the start of the 1972 season.

Blue remained one of the best starters in the game for the remainder of his tenure with the A's, but he was traded across the Bay to the Giants prior to the 1978 season. Blue posted a sub-3.00 ERA in three of his four seasons with the Giants before he was traded, this time to the Kansas City Royals. Blue faded over his two seasons with Kansas City.

Off the field, however, as Blue's career came to a close, he was one of several players caught in the crosshairs of the United States' failed War on Drugs.

Blue struggled with substance abuse, particularly alcoholism, throughout his life and was arrested for driving under the influence on at least three occasions, once as recently as 2005. During the 1980s, he had also used cocaine. In 1983, Blue was one of four players on the Royals who were sentenced to federal prison time stemming from drug charges. He was banned from baseball for the 1984 season and rejoined the Giants in 1985 on a minor-league contract. He made the team and had a pair of resurgent seasons before he hung up his cleats.

“It’s not embarrassing, but it tarnished my image,” Blue told the Washington Post. “Not that I was squeaky clean. I didn’t have a halo and [stuff], but I had a reputation of being a respectable, reputable person. I worked my tail off to polish that image back up and renew the name Vida Blue Jr. But it’s a constant battle to do that every day.”

While drug usage was rampant throughout the United States, particularly among MLB players, in the eighties, Blue was one of many Black players who faced much larger consequences than most of their peers. The suspension and damage to his reputation stemming from the 1983 drug case likely prevented him from reaching the Hall of Fame.

“Dammmmn. And I blew it,” he told the Washington Post. “That Hall of Fame thing, that’s something that I can honestly, openly say I wish I was a Hall of Famer. And I know for a fact this drug thing impeded my road to the Hall of Fame — so far.”

Despite his struggles with addiction following his playing career, Blue became an active philanthropist and often spoke publicly about his struggles. He was also a TV analyst for SF Giants games on NBC Sports Bay Area.

The entire Giants Baseball Insider team sends our condolences to Vida Blue's friends and family. He is survived by his son Derrick, and daughters Alexis, Valerie, Sallie, and Evelyn.