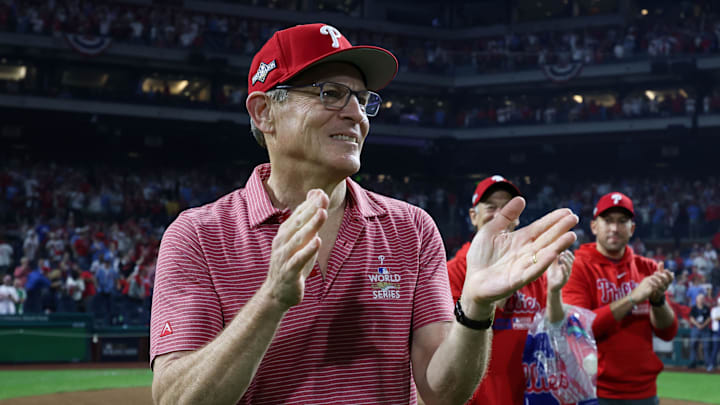

Phillies Owner John Middleton Provides an Unsparing Blueprint for His Peers

In this story:

The Philadelphia Phillies were a first-class organization in every way when catcher J.T. Realmuto arrived in February 2019—except one.

“I wouldn’t say I asked for a new plane,” he says. “But I did say there were better planes out there.”

For example, the Miami Marlins, the team that had traded Realmuto, flew a Delta Boeing 757 that had been fitted with custom card tables and extra first-class seats. The Phillies were flying a standard commercial United jet. So when he signed a five-year, $115.5 million deal to stay with Philadelphia in 2021, Realmuto casually mentioned the difference to president of baseball operations Dave Dombrowski. Dombrowski called his boss, team owner John Middleton. The next season, the Phillies were on the same type of plane Miami had.

So what did the change cost?

Middleton, taking a break from gathering balls during batting practice and handing them to fans, shrugs. “I don’t care,” he says. “I really don’t care. I do care if the players get on the plane and they’re like, ‘Aw man, look at these cheap SOBs.’”

No one would accuse Middleton of stinginess. The Phillies carry the fourth-highest payroll in the sport this season, at $242 million, according to Baseball Prospectus, the fifth straight year they’ve ranked in the top 10. But players and staffers say that what makes Middleton among the best owners in the game, and the man with whom they ultimately credit a sustained stretch of success that has them taking aim at a third straight deep October run, is his willingness to spend in areas other than player salary.

“This isn’t a job or an asset in his portfolio,” says right fielder Nick Castellanos. “He really wants to win. He’s not Santa Claus. But I think that he uses some really good judgment, and if our wants are valid and justified, he comes up [with it].”

As the collective-bargaining agreement works to restrict big market teams’ financial advantage when it comes to payroll, Middleton—the 69-year-old heir to a tobacco fortune—has redirected funds off the field.

“That was a big thing when I signed here,” says first baseman Bryce Harper. “Whatever is going to help this team be successful: training staff, food, clubhouse stuff, travel, anything you could really think of. He does just a very good job of understanding what guys need, what the team needs, what the staff needs as well. Not just players, but staff as well. Anything you really need, he’s going to deliver the best in the game.”

When Harper’s wife, Kayla, became interested in nutrition a few years ago, he began asking the team chefs to bring in pasture-raised, grass-finished beef and raw milk, much of it from Amish country. When players expressed frustration about the aging batting cages and interest in a new pitching machine that simulates pitchers’ deliveries, upgrades came quickly. When designated hitter Kyle Schwarber mentioned a craving for hibachi in Pittsburgh, “Sure enough,” he says, “We show up after the game and they have the spread and there’s hibachi there, too.”

In many cases, Dombrowski signs off on the changes without even going up the ladder. “It’s easy, if we’re doing something for them that maybe costs a little bit more, it’s not something we’ve got to run by John,” he says, “Because I already know what his mindset is.”

Middleton is matter-of-fact about the improvements. “I told Dave, since the day he arrived here: ‘Your job is to figure out what you have to do to put a championship team on the field,’” Middleton says. “‘My job is to figure out how to get you the money to put the championship team on the field.’

“But that championship team goes beyond just the player. You buy the batting cages and the players walk in and go, ‘Wow, O.K., I like this. We were unhappy. We now have new batting cages. I’m happy. I feel better.’ ‘We’re now wearing red jerseys. I feel better.’ ‘We have a new plane. I like that. That’s really nice.’

“All those things just make people feel comfortable where they are. It makes them like where they are more. I love when people are happy and contented. They can focus on their job. You know, we’re not just throwing money at them because we just like throwing money at them. It means there’s a reciprocal obligation, which is: I’m trying to remove impediments to your happiness, so you can focus on what I want you to focus on, which is winning. And I want you to come back as hard and fast as you can if you're injured, and I want you to play as hard as I can every day. That’s what I expect. And I don’t want you grousing to your former teammates, ‘This guy’s a real cheap guy who flies a lousy plane and we eat peanut butter and jelly sandwiches.’”

He has always liked the term “management by wandering around,” which he learned about reading Tom Peters and Robert H. Waterman’s 1982 management tome, In Search of Excellence: Lessons from America’s Best-Run Companies.

“The best CEOs don’t hide behind a desk in an office,” he says. “They're out in their business. They're talking to customers and talking to employees.”

Does picking up balls after batting practice fall into that category? He grins. “Yeah, doing that,” he says. “But the book made a big impression on me, and [especially] that particular aspect, management by wandering around. So I’ve been doing that all my business life, and there’s so much you can get out of it. My dad always taught me that the best ideas aren't limited to a few people. You can get great ideas throughout the organization. He literally would take important letters or memos out to the bullpen [where the assistants sat] and ask people to read this letter and say, ‘When you finish it, come on in and tell me what you think.’”

So he chats with players and helps staffers with small tasks. “It’s kind of crazy,” says shortstop Trea Turner. “He’s, like, never in the way. He’s in the middle of everything, but you don't necessarily notice him unless you look for him.”

Middleton sees the benefit of his involvement every time the organization considers acquiring a star player. In those moments, he says, “You need a lot of feedback. And I think the thing that we're most looking for is questions about the players’ character, and whether they’ll fit into the clubhouse. We can see whether somebody hits .320 or .280. The issue is: What else do they bring to the party? I think in order to have those conversations that are really truthful and insightful, you’ve gotta have a relationship. You can’t just walk into a stranger’s locker and start asking those questions.”

He used to worry that he might undermine his baseball operations people, but he has learned when to stay out of the way—and to take their advice. One year players asked to move the annual family trip from one city to another. Middleton checked with Dombrowski, who explained that they’d chosen the date on purpose because they did not want players distracted down the stretch. They kept the family trip where it was.

“I have to be part of that overall effort to support it,” he says. “Because you can get a situation where you've got a really good manager, a really good general manager and the owner’s not, and it's kind of like, O.K., we have to fight for everything. You like us and you like us, and you try to help us, but that person over there is always saying no.”

So he tries to say yes as often as possible. For the annual alumni weekend, Middleton buses all the former Phillies and their families—a few hundred people—to his house and sets up a tent and tables. He covers the cost personally. “I think it’s good, and the alumni like it, and they feel appreciated,” he says. “And they should. I want them to.”

When the team won the National League pennant in 2022, he bought the nicest rings he could, and handed them out to everyone in the organization and to everyone on the team’s wall of fame. He also paid for each player to have a second copy of the ring made as earrings or a pendant for an important person in their lives.

“Could we have saved a bunch of money by making a less nice ring, by not giving the wives or significant others [gifts]?” he says. “It’s money, but it’s not that much money. I know a little bit here and there can add up. Senator [Everett] Dirksen had that great quote. (On the subject of federal spending, the Republican of Illinois is said to have said, ‘A billion here, a billion there, and pretty soon you’re talking real money!’)

“But I think it’s part of building the culture of an organization, that people really want to come here. In the long run, we’re gonna be remembered for whether we win pennants and World Series titles or not. If you can make decisions to spend this money and make players happier and bring players here, it’s special. You know, Zack Wheeler gave up money to pitch here. Cliff Lee gave up $26 million to pitch here rather than somewhere else! That’s important. And by the way, I like these players as human beings. They’re nice people. I genuinely like them.”

And he believes his legacy will be measured in trophies, not dollars. He thinks back to the juggernauts in baseball history such as the 1927 Yankees.“Did they make money?" he says. "They probably did. I’m guessing. I don’t know. Do you really care? Not even a little bit. Nobody cares whether I make money or not.”

Apparently, including him.

He shrugs. “My great-great grandchildren might be angry at me,” he says. “But I’m not going to know them!”

Stephanie Apstein is a senior writer covering baseball and Olympic sports for Sports Illustrated, where she started as an intern in 2011. She has covered 10 World Series and three Olympics, and is a frequent contributor to SportsNet New York's Baseball Night in New York. Apstein has twice won top honors from the Associated Press Sports Editors, and her work has been included in the Best American Sports Writing book series. A member of the Baseball Writers Association of America who serves as its New York chapter vice chair, she graduated from Trinity College with a bachelor's in French and Italian, and has a master's in journalism from Columbia University.

Follow stephapstein