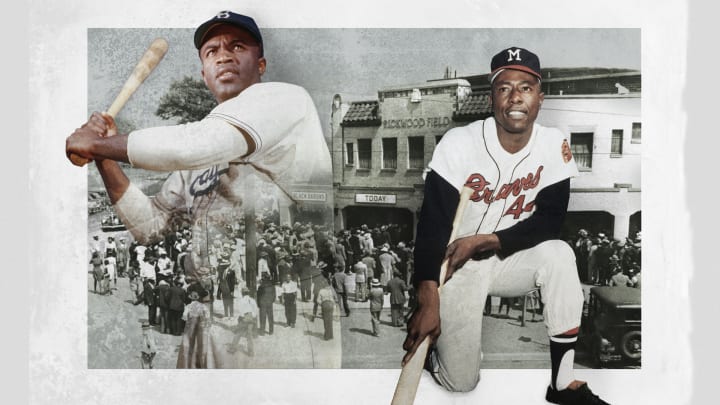

Rickwood Field Was a Scene of Change for Jackie Robinson and Hank Aaron

The small room will have to do. The most famous ballplayer chasing the most famous sports record and his attendant crowd of reporters squeeze into the office of Glynn West, the general manager of the Double A Birmingham Athletics. Rickwood Field was built in 1910, before electric traffic lights, the Titanic, commercial radio and the American media circus. It wasn’t built for this. West’s walls are covered with photos of other minor leaguers who made their way through Rickwood, some of them while West was working the manual scoreboard in ’48.

Henry Aaron, in full uniform, holds a press conference less than 30 minutes before the last full baseball game he will play with fewer home runs than Babe Ruth. “Hank, is it tough to answer the same question over and over?”

“It’s easy. No, it’s not tiring either.”

It is Tuesday, April 2, 1974, just past 6 p.m. Aaron and the Braves are about to play the Orioles in a final exhibition game before their opener Thursday in Cincinnati. The air is charged with controversy. Aaron has 713 career home runs, one short of Ruth’s record. Three weeks earlier, commissioner Bowie Kuhn rejected the Braves’ plan to sit Aaron in Cincinnati so he could try for the record-tying and record-breaking home runs in front of his home fans. Kuhn ordered Aaron to play in at least two of the first three games.

“Hank, what do you think of the commissioner’s ruling?”

“I’ve never talked to Mr. Kuhn ... I think this whole thing has been blown out of proportion. I’ve always said, and I have mixed emotions about it, that a ballplayer wants to do what is right ... Certainly I would like to hit the two in Atlanta.”

Aaron fidgets in his seat. Game time is approaching. A columnist will bang out on his typewriter that Aaron looks like “an old fire horse when the alarm sounds.”

Aaron makes his way to the field. The dugouts at Rickwood are subterranean, waist-deep, like an archeological dig. The exit is up a small staircase at the far end of the dugout. Suddenly, as if appearing from a trap door in stage floorboards, the broad back of the familiar No. 44 in Braves’ blue emerges into the dreamy watercolor pool of dusk and stadium lighting. The sellout crowd erupts. The roar can be heard by reporters lingering in West’s office. This is Hank Aaron night at Rickwood, a tribute to the home-run-king-in-waiting, who grew up 250 miles away in Mobile.

A microphone is set up behind home plate. Alabama governor George Wallace is running for a third term after first gaining office on a “segregation forever” platform, but he had a previous commitment. Wallace in his stead sends Travis Tidwell, a former Auburn football star. Tidwell presents Aaron with a commission in the Alabama navy. Next, the mayor of Birmingham, George Siebels Jr., hands Aaron the key to the city.

Then Braves announcer Milo Hamilton introduces the man of the hour. Aaron has turned 40 years old. His belly presses against his polyester jersey. His puffy eyes are weary. The past year has been hell, with hundreds of letters filled with racial insults and death threats that had to be vetted by the FBI. He left ballparks by back exits. He needed police escorts. His children lived under threat of kidnapping. He said he felt “like a pig in a slaughter camp.”

He steps to the microphone, facing the single-level grandstand of Rickwood. Not much has changed since Henry played his first game here in 1952 with the Indianapolis Clowns of the Negro American League. He looks up and sees the grandstand’s kite-shaped canopy, held up by steel beams and a web of muscular steel trusses. Atop the roof he sees the same five 75-foot-tall steel light stanchions that since ’36 have stood watch omnipotently over Rickwood, which still stands today and was chosen by Major League Baseball to host a regular season game this summer between the St. Louis Cardinals and San Francisco Giants.

On the roof directly in front of him is a wooden gazebo, looking to most people as quaint as a steeple atop a church. When Henry sees it, he knows its dark history.

The gazebo was the original press box. It launched the career of Theophilus Eugene “Bull” Connor, popular play-by-play radio announcer for the Birmingham Barons in the 1930s. So popular was Bull that he ran for state legislature in 1934 “just for the fun of it.” He won. From that day until his death just 13 months before Hank Aaron night, Bull, an avowed segregationist and the most powerful man in Birmingham, personified the Jim Crow South.

Henry scans the crowd, which numbers more than the official count of 9,140. He sees people standing and sitting in the aisles. He sees Blacks and whites sitting side by side. He sees Blacks and whites together in each dugout. In this way Rickwood is nothing like the Rickwood he knew as a young man. The idea that a Black man would be honored with the key to the city—of all cities, Bull’s city, known as “Bombingham” for how whites clung violently to segregation—was unfathomable then.

Hands on hips, Henry leans into the microphone.

“I first played in this park almost 20 years ago against the Birmingham Black Barons,” he says, though it’s been 22 years. “I played here with the Indianapolis Clowns in those days 20 years ago. I never suspected then what was in store for Hank Aaron.”

The Kuhn “controversy” is nothing. It is nothing compared to the racial animus Aaron endures. Nothing compared to the segregated history of Rickwood, where the Ku Klux Klan held huge rallies in the 1920s, where Negro League players like Hank were forced to dress in Black-owned motels because they were barred from using the clubhouses, and where Blacks who attended Barons games and whites who attended Black Barons games could sit only in a quarantined section of the farthest right field bleachers, a chicken-wire partition separating them.

Birmingham was, in the words of Martin Luther King Jr., “the most segregated city in America.” Not until 1963—16 years after Jackie Robinson debuted with Brooklyn and seven years after he played his last game—did Birmingham allow Blacks and whites to play together in any kind of game. Even a mixed-race game of checkers was unlawful, which is how the local ordinance became known as the Checkers Rule.

There was, however, one brief, serendipitous exception to the ordinance. Over a seven-day span in April 1954, Rickwood hosted five exhibition games involving integrated major league teams making their way north for Opening Day. It happened in a rare sliver of time when Bull let his guard down.

The Brooklyn Dodgers played the Milwaukee Braves in the second and third of those games. The starting left fielders were Robinson, then 35, and Aaron, then a 20-year-old kid just 11 days away from making his major league debut.

And then segregationists like Bull quickly restored the Checkers Rule. It would be another 10 years before Rickwood hosted another mixed-race game.

But for those two days in 1954, Hank got to play on the same field in the most segregated city in America with Jackie, the man who inspired him, in a color-blind, almost ethereal world of equality. How those games came about—and how the Bull Connors of the world fought this integrated American future to their last breath with legislation, bombs, dogs, water cannons and burning crosses—is the incredible story of how baseball, as Aaron liked to say, pressed the issue of integration in a very public way.

“It was,” he said, “our civil rights laboratory.”

It is 20 years to the day after the first of those historic, mixed-race Dodgers-Braves games. Bull is dead. Hank is exalted. Many of the people here at Rickwood are the children and grandchildren of those who saw the Babe play exhibitions here. They heard the legend of how Ruth hit the “longest” homer ever at Rickwood: a blast over the right field wall that landed in a passing train car, never to come to a stop until the train pulled into Atlanta.

A chilly wind blows in from right field. As he always does, Henry chooses his words carefully and purposefully. They leap from the microphone, clatter and echo around the concrete and steel skeleton of old Rickwood and land softly on the souls of anyone with a shred of empathy.

The Babe is right in front of him. But because this is Birmingham, tonight is more about what is behind him.

“I didn’t know what was in store ... but I’ve worked very hard to get there. And thank you.”

The face of segregation was a one-eyed, bespectacled sallow mien with a high forehead and turned-down mouth, topped usually by a straw hat. Bull Connor looked exactly like his name sounded. Born in Selma in 1897, he never graduated high school. He preferred playing baseball and traveling with his father, Hugh King Connor, a telegrapher for the Great Northern Railroad. He learned his father’s trade well enough to land dispatcher jobs around the country before returning to Birmingham to work in radio.

He quickly became known as Bull, partly because of Dr. B.U.L. Conner, the cartoon character under which editor E.T. Leech wrote for the Birmingham Post in the 1920s, but also partly because of his booming voice. Connor used it like a bullhorn as he shouted telegraphic baseball reports through a megaphone into the pool halls of Birmingham.

At the dawning of its golden age, radio made him a star. Fans loved the way he would butcher the English language with homespun charm and the way he would draw out his calls for dramatic effect, especially his signature “o-uuuuu-t.” From that gazebo, Bull was an unabashed showman.

“Pretty good announcer, too, although I think he used to get too excited,” recalled a young listener in nearby Fairfield who would grow up to become a pretty good center fielder himself: Willie Mays.

(Mays died at age 93 on Tuesday, just two days before he and his fellow Negro Leaguers are to be honored at a game between the Giants and Cardinals at Rickwood. Mays was born nine miles away from Rickwood in Westfield, he attended many games there with his father and at 17 he debuted there with the Birmingham Black Barons, playing only in weekend home games because his dad did not want him missing high school classes. Rickwood is the cradle of the career of the greatest all-around player who ever lived. Two days after his death, it is where the world says goodbye.)

Power was Bull’s sustenance. He leveraged his popularity into his seat in the Alabama House of Representatives in 1934 and then in ’37 as Birmingham’s Commissioner of Public Safety, which gave him command of the police and fire departments, schools, parks, public health services and libraries. He was unapologetic about what he believed in: ridicule over logic, intransigence over compromise and, most of all, white over Black.

Even as the civil rights movement gained strength in America, Bull made certain nothing much changed in Birmingham for the next 15 years. But the status quo could not last. Led by Jackie Robinson, the “civil rights laboratory” of baseball helped fuel the inevitable reckoning not even Bull could stop.

A boy sitting with his father on the back porch of their Mobile, Alabama, home looked up in wonder at a plane traversing the sky.

“When I grow up, I’m going to be a pilot,” the boy said.

His father shook his head.

“Ain’t no colored pilots.”

“Then I’m going to be a ballplayer.”

“Ain’t no colored ballplayers.”

Then in 1947, Jackie made his debut with the Brooklyn Dodgers. Later, Herbert Aaron would take his son to see Robinson when he came to Mobile for an exhibition game. Henry remembered it as taking place in ’48, but more likely it was Oct. 31, 1950, when Robinson brought his barnstorming all-star team to Mobile to play the Indianapolis Clowns. The game was played at 1:30 p.m. on a Tuesday afternoon, which would have required an absence from school for Hank to attend.

Well before the game that day, Robinson, dressed in a suit and tie, spoke to a crowd of mostly young Black men in front of the Davis Avenue Pharmacy. Perched on the edge of Mobile, and just a half mile from Aaron’s home, Davis Avenue—officially and ironically, Jefferson Davis Avenue—was the heart of the Black community. The Avenue, as the locals called it, thrived with Black-owned businesses and shops. Hank was in the crowd as Jackie told the young men they could dream of playing baseball but advised them to stay in school because not all would be good enough to make it.

“If it were on videotape, you’d probably see me standing there with my mouth wide open,” Hank later recalled. “I don’t remember what he said. It didn’t matter what he said. He was standing there. [Then] my father took me to see Jackie play in that exhibition game.”

Herbert and Hank were among the 7,000 or so people, most of them Black, who filled Hartwell Field. (White fans were given access to reserved seats.) They were treated to pregame entertainment from comedians King Tut and Spec Bebop and then a thrilling game that featured Black stars such as Robinson, Roy Campanella, Larry Doby, Don Newcombe and Ernie Banks. Robinson singled, tripled and scored twice in a 3–2 win by his all-star team. Hank and his father returned home with a new idea of what was possible. “After that day,” Hank said, “he never told me ever again that I couldn’t be a ballplayer. I was allowed to dream after that.”

On Sept. 9, 1950, the Chicago Cardinals played the Detroit Lions at Legion Field in Birmingham as part of an annual NFL showcase game known as the Pro Bowl. Wally Triplett, a Black halfback with the Lions, was allowed to warm up with this team but was not permitted to play in the game.

A year later, the New York Giants played the Washington Redskins at Legion Field. Defensive back Emlen Tunnell and fullback Stonewall Jackson, Black players for the Giants, had to watch the game from the stands. The Pro Bowl was then suspended.

Five months later, on Feb. 8, 1952, a Jefferson County grand jury released a 15-count impeachment recommendation of Connor—whose brashness rubbed wrong many underlings and fellow city government officials. The grand jury cited him for “commission of offenses involving moral turpitude, corruption in office and incompetency,” including the assault of a City Hall switchboard operator, his arrest after being caught in a downtown hotel room with his secretary (who was not his wife) and the use of prisoners to do his yard work.

The grand jury concluded, “He listens to no advice and learns neither from his friends, his enemies nor experience; he cracks the whip of authority but uses no persuasion, logic or reason, if any he has.”

Bull fought back. A month later, a judge threw out the two morals charges, arguing that even if they were true, they were not impeachable offenses. Bull’s impeachment trial ended in a mistrial when the jury could not reach a verdict. He was impeached again. Another mistrial. More impeachment proceedings were planned.

More than any city, Birmingham stridently if awkwardly maintained legal separation of races in almost all walks of life, including bathrooms, restaurants and ball games. Section 597 of the 1944 city code was titled “Negroes and Whites Not to Play Together.” It stipulated, “It shall be unlawful for a Negro and White person to play together or in company with each other in any game of cards or dice, dominoes or checkers.” Section 597 was supplemented in 1950 with Ordinance 798-F, which added to the list of named games “baseball, softball, football, basketball or similar games.” Violators were charged a misdemeanor and fined up to $100 and jailed up to six months.

Meanwhile, as 1953 began, Connor ran for another term as commissioner. He promised he would never allow Blacks on the police force, and he would never allow whites and Blacks to play baseball together.

“If they play together, you’ll have to let them sit with you in the stands,” he told his white audience.

On Feb. 28, Connor, then 56, suddenly announced he was dropping out of the race for a fifth term. The move had one obvious benefit: He could finish out his term while the third impeachment trial became moot. It was dropped.

Meanwhile, the success of the Barons created a potential problem for Connor and the other two commissioners, mayor James Morgan and Robert Lindbergh. If the Barons won the championship of the all-white Southern Association, they would then host the Texas League champions—who would have Black players—in the Dixie Series.

On Sept. 17, Morgan announced that the commissioners would repeal Ordinance 798-F at their meeting five days later. Morgan explained he understood the Checkers Rule to be unconstitutional and that a repeal “will be in keeping with the attitudes of citizens throughout the South, Southeast and Southwest.” He noted Blacks were allowed to play on teams throughout the South and a repeal would allow Birmingham to host MLB exhibitions the next spring.

But when the meeting began, 90 people were on hand to protest the repeal. The commissioners suddenly changed their minds. They decided not to repeal it. Connor was not in attendance. He was in Canada on vacation.

The threat to Ordinance 798-F was avoided when the Barons lost in the finals. But another threat was around the corner. Robinson’s barnstorming all-star team slated to play at Rickwood in October had three white players: Gil Hodges, Ralph Branca and Al Rosen. Bull would have none of it.

“There is a city ordinance that forbids mixed athletic events,” he said.

Robinson sat his white players, explaining that the tour’s promoter was responsible for arrangements, not him. About 6,000 people watched Robinson’s all-stars beat a team of Negro League all-stars, 10–4. Robinson had two hits. Mays, home on Army furlough, had two hits and a steal of home.

The Birmingham World, a Black-owned newspaper, reacted with incredulity: “If Birmingham does not want mixed sports competition, and Jackie has such a team, why would he allow it to be booked in this city? Why would Jackie bow to bigotry? Why would he bring three white players here to be benched by bigotry?”

The great Red Smith wrote in the New York Herald Tribune, “It was a mistake on his part. Robinson is keenly and properly conscious of his importance in the Negro’s struggle for recognition. Here was an opportunity to dramatize the cause in far more sympathetic circumstances than Jackie has encountered on other occasions. He blew the chance.”

Upholding the Checkers Rule against Robinson’s team was one of Bull’s final acts as commissioner. Two weeks later, on Nov. 2, 1953, Wade Bradley, a 38-year-old former preacher, Marine and Air Force veteran, police officer, FBI agent and deputy sheriff, was sworn in to replace Connor. Bull was given a silver tea set as a going-away present. Ever the showman, he gave three farewell speeches. In one of them he said, “All my success I owe to the city employees—from the Negro who paints the street signs on up to the mayor.”

Just two months after Bull was gone, the three commissioners voted to allow Blacks and whites to play baseball and football together. Morgan, Lindbergh and Bradley did not abolish the Checkers Rule, but dropped from the ordinance the words “baseball,” “football” and “or similar games.” The rest of the prohibitions stood. On that same day, it was announced that the Braves would play the Dodgers on April 2 and 3 at Rickwood.

Resistance quickly formed. A group calling themselves the Citizens Segregation Committee took out ads in local newspapers urging citizens to pack a city commission meeting. On the day of the meeting, a crowd about 200 strong demanded a repeal of the repeal. They erupted in a chant of “Put Bull Connor back in here!”

Morgan kept pounding his gavel, trying to silence them. “Order! Order!” he demanded, but to little effect.

A 69-year-old attorney named Hugh Allen Locke—the progeny of the reconstructed South, a man whose father served four years as a Confederate soldier—came forward to speak for the group. In words that in some form had been spoken ever since Appomattox, Locke pleaded to the commissioners, “Just put things back where you found them.” He demanded the repeal of the Checkers Rule be put up for public referendum.

“If you get 5,000 people to sign a petition,” Morgan told Locke, “you can get a referendum.”

Locke got 10,000 signatures, which just happened to match the estimation of Klan members in the city. The referendum was scheduled for June 1, 1954. It was known as the Locke Recall Petition. In the meantime, across the miracle of seven days of suspended segregation, baseball would be played in Birmingham like no one had ever seen.

Jackie and Hank had known each other since 1952, two years after Hank skipped school to hear Jackie speak on The Avenue. Hank was a skinny, cross-handed hitting teenage shortstop with the Clowns when he happened to room with Jackie during an exhibition tour. In ’54, they drew closer as the Dodgers and Braves played a six-game exhibition series from Jacksonville to Mobile to Birmingham to Nashville to Chattanooga leading to Opening Day.

Because of segregation laws, the Black players stayed at separate hotels from their white teammates. And within those hotels, the Black players of both teams spent many hours together: Robinson, Roy Campanella, Don Newcombe, Joe Black, Sandy Amoros and Junior Gilliam of Brooklyn and Bill Bruton, Jim Pendleton, Charlie White and Aaron of Milwaukee. They played pinochle, talked baseball and discussed the survival strategies that a Black man needed on and off the field. “Jackie Robinson was about leadership,” Aaron would recall. “When I was a rookie with the Braves and we came north with the Dodgers after spring training, I sat in the corner of Jackie’s hotel room, thumbing through magazines, as he and his Black teammates ... played cards and went over strategy: what to do if a fight broke out on the field; if a pitcher threw at them; if somebody called one of them ‘n-----.’ ”

The game in Jacksonville on March 31 was a 10–7 shootout won by the Braves that took so long the teams agreed to end it after eight innings so they could catch their trains to Mobile. While the Braves and Dodgers played at Hartwell on April 1, the White Sox and Cardinals played at Rickwood in the first integrated game in Birmingham’s history at 2 that afternoon.

In the Birmingham Post-Herald that morning, Naylor Stone wrote, “This afternoon will be the first time in our town that white and Negro players have performed at the same time. And when games to follow this Spring are completed, our fans will have seen some of the greatest Negro players.”

Over the next seven days, a Birmingham fan could watch Robinson, Campanella, Newcombe, Aaron, Bruton, Mays, Monte Irvin, Larry Doby and Minnie Miñoso, not to mention white future Hall of Famers Stan Musial, Gil Hodges, Pee Wee Reese, Duke Snider, Eddie Mathews, Warren Spahn and Richie Ashburn.

History was made in Birmingham on April 1 in the top of the first inning when Bob Boyd, a former Negro League player with the Memphis Red Sox, jogged to left field for the White Sox, and Miñoso, who was signed off the New York Cubans, ran to third base. Tom Alston, a 28-year-old Cardinals rookie first baseman from Greensboro, N.C., was the first Black player to come to bat in Bull Connor’s worst nightmare. He reached on an infield single. The Cardinals won, 7–4, in front of 2,950 people.

“There were almost 1,000 Negro spectators at yesterday’s game, most of them interested in watching Negroes play with white players in the first ‘mixed’ baseball game at Rickwood,” the Post-Herald reported. “And the first ‘mixed’ game went off without a hitch. There were no boos, and applause was heard when the Negro batters came to the plate.”

The Dodgers and Braves played the next two days. Because of Jackie, the crowds were much bigger, and, according to Aaron, not as benign as what the Post-Herald had reported.

In an oral interview Aaron provided for Baseball Has Done It, a 1964 book by Robinson, Aaron said: “The last time a major league team was in Birmingham was when the Braves played the Dodgers one spring. I never heard so many curses in my life. The Dodgers had seven or eight Negro ballplayers, all very good. Campy, Newcombe, Joe Black, Jackie, to name a few. I don’t think Jackie or Campy played the whole game—about four or five innings, that’s all. And Newcombe came in in the sixth inning. I never heard such filth in my life. They wasn’t giving it to us. They was giving it to Jackie and Campy and Newcombe.”

The Braves routed the Dodgers on Friday afternoon, 17–2, in front of 4,823 fans. A lefthander named Tommy Lasorda pitched the final three innings for Brooklyn. Aaron, wearing No. 5, had three hits, backing up the pregame boast of his manager, Charlie Grimm, who said, “He’s bound to become a great star.”

Brooklyn bounced back on Saturday afternoon with a 9–1 win. Dave Anderson reported in The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, “The crowd was 10,474 with Negro fans overflowing against the outfield walls.” More than two-thirds of the crowd were Black. They saw Jackie get two hits, Campanella get three, Gilliam make three circus catches, including one that robbed Aaron of a hit, and Bruton take a home run away from Carl Furillo while falling into the crowd in center field.

The games were a success, at least in the eyes of the whites who organized them, leaving many to believe they had watched Birmingham’s halting first step toward joining the integration of America.

“However,” the Wisconsin State Journal wrote after the game Friday, “a die-hard element has petitioned for a referendum on the subject, and it is to be voted on in the spring. Those who should know say that the petition to reinstate the sport segregation law will be defeated in the spring.”

Two months later, Birmingham, a city of about 200,000 whites and 120,000 Blacks, voted on the Locke Recall Petition. The voters overwhelmingly chose segregation, by a margin of more than 3 to 1. The vote, Locke said, “indicates that the people of Birmingham are not going to take [the end of segregation] lying down. And it tells that to the people of the United States.”

Only upon the outcome did Morgan explain that he had offered the repeal of 798-F only as it pertained to pro sports.

“I now and always have been for segregation of races,” he said. “I’m definitely and emphatically against intermingling of races in such places as swimming pools, parks, schools, theaters and other places.”

The vote signaled that segregation would remain in Birmingham for years.

So did the return of Bull Connor.

After the end of his term Nov. 2, 1953, Connor operated a service station in Avondale. His thirst for power did not abate. In May 1954 he ran for Jefferson County sheriff. He lost by nearly a 2-to-1 margin. In ’56, he ran for City Commissioner of Public Improvements, taking out ads that announced, “Eugene (Bull) Connor believes in the segregation of races ... Bull Connor will not tolerate ‘meddling’ of outside interests in the most serious problem of our time.” He scored a narrow win over Lindbergh.

Returned to power, Bull found himself confronting a new adversary: Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth, who in 1956 founded the Alabama Christian Movement for Human Rights, which took dead aim at Bull’s beloved segregation laws. The next year Shuttlesworth teamed with King and Rev. Joseph Lowery to establish the Southern Christian Leadership Conference.

Few men bore the wrath of segregationists like Shuttlesworth. His home was bombed on Christmas 1956 (from outside his bedroom, with him in the bed), he was beaten in ’57 by thugs with baseball bats and bicycle chains when he tried to enroll two of his daughters in a white elementary school and his church was bombed three times, the last while children were rehearsing a Christmas pageant. Nothing stopped him.

“I think God created Fred Shuttlesworth to take on people like Bull Connor,” Lowery said.

In May 1963, Shuttlesworth, then 41 years old, was hospitalized after being struck by a blast from a high-pressure fire hose.

“I waited a week to see Shuttlesworth get hit with a hose,” Connor sneered. “I’m sorry I missed it.”

Connor was told Shuttlesworth had been taken away in an ambulance.

“I wish they’d carried him away in a hearse,” Bull scoffed.

By then, television had long replaced radio as the dominant American medium. The news footage of Connor’s tactics of deploying police dogs and fire hoses against peaceful protesters was so abhorrent that Bull gave unintended Godspeed to the civil rights movement.

Meanwhile, Shuttlesworth fought Connor in the courts, not just the streets. In 1961 he was one of 15 people to file suit seeking to desegregate the city’s parks and recreation facilities. They won. U.S. District Judge H. Hobart Grooms ruled the ordinance unconstitutional. He ordered the immediate desegregation of Birmingham’s 67 parks, 38 playgrounds and four golf courses.

“If that is true,” Connor said, “then I will never appropriate a dime more than what the law says must be appropriated to the Parks Board. ... There’s never been any doubt in my mind that you would have bloodshed if you allow both races to use the same pools, parks and golf links.

“Therefore, as public safety commissioner of the City of Birmingham, I think it is my duty to close all of them.”

The city filed an appeal Nov. 29, an act that kept the Checkers Rule in place and the parks closed. On that same day, Barons owner Arthur Belcher pulled the Barons out of the Southern Association, ending a membership that dated to 1901. Birmingham chose to shutter its baseball team rather than integrate.

“I never regretted anything so much in my life,” said Belcher, “but I felt there was nothing else I could do.”

Bull said he was prepared to fight “all the way to the Supreme Court if necessary. If people want the law changed, let them change it. But as long as it is on the books it will be enforced.”

Rickwood stood empty in 1962. Legion Field was one of the few public parks that remained open. Georgia played Alabama there in a football game on Sept. 22, 1962. As the fourth quarter began, two Black men left their seats in the south end zone. According to a local report, these men were “apparently the first of their race to integrate a public sports event here.” By the time the men arrived outside the stadium gate, a crowd of 100 white men stood waiting for them. One man was able to escape on foot. The other was badly beaten.

Six weeks later, citizens of Birmingham made a massive change in how the city should be run. They elected to end the commission form of government and adopt a mayor-council structure. On Jan. 5, 1963, a judge upheld the vote, whereupon Bull announced, “I’m a candidate for mayor.”

Running against Albert Boutwell, also an avowed segregationist but who indicated a willingness to work with local leaders, Connor doubled down. He said he would close the schools before he would integrate them.

“I will never as long as I am in City Hall integrate them,” he promised.

On April 3, 1963, in the biggest voter turnout in Birmingham city history, Boutwell won, 29,630–21,648. Boutwell carried the predominantly Black polling places of Legion Field and Washington School by a count of 2,527–5. Boutwell won virtually every district, including Bull’s home district. Connor effectively was finished as a political power broker, though he would serve as president of the state public utilities agency until a year before his death in 1973.

Without him, a new era was about to begin, though slowly, painfully and violently. The tinderbox that was Birmingham exploded in 1963. King was jailed in April for peacefully protesting, whereupon he wrote his famous “Letter from Birmingham Jail.” In May, as children joined the protest movement, Connor ordered local officials to use force to stop them, including fire hoses and police dogs. Wallace and Connor spoke at a Labor Day rally and defended segregation as Klansmen set off several bombs timed around the opening of schools. Two weeks later, four children were killed at the bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church. Amid the strife, the new nine-member city council embraced change. On July 23, 1963, it unanimously repealed all segregation ordinances, including the Checkers Rule.

The Barons returned the following year. On April 17, 1964, they opened the season against the Asheville Tourists. It was the first integrated baseball game at Rickwood since Jackie’s Dodgers and Hank’s Braves played in that spectacular but brief week of hope 10 years earlier.

Aaron awoke for the first time as the new home run king around 9 a.m. He had slept only three hours.

“When I got home, I was the most relaxed I’ve been in the last year and a half,” he said. “I was just grateful that it was over with. I slept well.”

Aaron hit number 715 against Dodgers pitcher Al Downing on Monday night, April 8, 1974, in Atlanta—50 years ago. Thirty-five million people watched on television. President Richard Nixon, who 22 days later would give a televised address about the Watergate scandal, immediately placed a phone call to congratulate Aaron.

Kuhn wasn’t there. The commissioner had skipped the historic event to speak at a private event in Cleveland. Two days after Hank spoke at Rickwood, Aaron had tied Ruth with his first swing on Opening Day in Cincinnati. His manager and former teammate, Eddie Mathews, decided to sit Aaron for the next two games to ensure that he would chase the record at home. But after the second game, Kuhn telephoned Mathews and ordered him to play Aaron in the third game.

“I resent that, yeah,” said Mathews, who grudgingly followed orders.

Aaron went hitless on Sunday in Cincinnati. It chafed him that pundits accused him of not trying his level best. He wanted this damn chase over. After a first-inning walk, he smashed 715 in the fourth inning at 9:07 p.m. with his first swing of the night.

Asked to address the crowd, the first thing that came out of his mouth was, “Thank God it’s over!”

He spent that night at home with friends and family. They stayed up chatting until 4 a.m. Hank finally went to bed at 6.

By the time Hank reported to the stadium for the next game—he was not in the lineup; manager’s decision stuck this time—he was exhausted.

“Just tired. All I felt was tired. And relieved,” he said when asked how he felt. “The average person doesn’t realize what a nightmare this has been, the same questions every day, the controversy ...”

The enormous effort under unrelenting pressure and prejudice is what Aaron was trying to convey when he spoke at Rickwood six days earlier: “I didn’t know what was in store ... but I’ve worked very hard to get there.”

Twenty years earlier, as the 10 Black players from the Dodgers and Braves bonded over their six-game tour of the Jim Crow South, Hank gained a deeply personal appreciation of Robinson’s contribution to baseball and social justice. The lesson would inform Aaron’s pursuit of Ruth. Through Jackie, young Hank learned that true success for a ballplayer was different for Blacks than for whites. For Blacks, it could never be measured in individual achievement, even the biggest of them all, the home run record. It was bigger than that. It was measured in how you represented your people.