Rickwood 101: Everything to Know Before MLB’s Negro League Tribute Game

In the last hour of sweltering daylight and the promise of cooler evening air, in a place of gargoyles and ghosts, shame and strife and the story of 20th century America writ in hallowed ground, Major League Baseball will stage one of its most important regular-season games ever on Thursday in Birmingham, Ala. The San Francisco Giants and St. Louis Cardinals are playing at Rickwood Field, America’s oldest ballpark, which turns 114 years old next month.

Rickwood is the Mother Church of Baseball. She looks more spectacular than ever thanks to a $5 million facelift for this game. Age alone does not make her sacred. The game Thursday is a tribute to the Negro Leagues and to Willie Mays, who was as a 17-year-old high schooler debuted in 1948 with the Birmingham Black Barons, who from 1920 to ’60 called Rickwood home. After Mays’s death on Tuesday, the game at Rickwood will seemingly feel even more meaningful.

Baseball succeeded wildly with its Field of Dreams games in Dyersville, Iowa, in 2021 and ’22. Those games were eye candy, as well staged as a movie set. They tapped into the romance of baseball as captured in a movie script.

MLB at Rickwood is bigger. It taps not into fiction but into real American history, especially the kind that needs to be remembered. American pride and prejudice echo within an ancient ballpark.

Rickwood was home to both the Barons of the all-white Southern Association and the Black Barons, though fans and players were segregated by Jim Crow laws. It wasn’t until 1963 that it was legal in Birmingham for Blacks and whites to play a game of baseball together.

Rickwood holds no secrets, but the stories it holds must be remembered and told. More than one-third of the players in the Baseball Hall of Fame played on this field. Christy Mathewson, Walter Johnson, Satchel Paige, Whitey Ford, Jim Palmer and Rollie Fingers pitched on its mound. Ty Cobb, Oscar Charleston, Babe Ruth, Hank Aaron, Mickey Mantle and Reggie Jackson all roamed the enormous outfield.

Stories. What is a revered place without the stories? Rickwood bursts with stories.

Stories like the time the Babe hit a home run that traveled 147 miles, or the single by the 17-year-old Mays in the last Negro World Series, or Jackie Robinson and Aaron being the starting leftfielders in the same game, or the one spring when Ted Williams, Joe DiMaggio and Mays played at Rickwood just weeks apart … or how the face of racial segregation in Birmingham, city commissioner Eugene “Bull” Connor, developed his popularity first from the press box gazebo atop the Rickwood roof as the play-by-play voice of the Barons.

RELATED: SI’s Best Stories About Willie Mays

No ballpark is older. No ballpark has seen so much baseball history. When you watch the game, you will be struck by the 75-foot tall, cantilevered iron light towers that hang over this wonderful stage like five deus ex machina. But there is no plot device here, no divine intervention, no “if you build it …” memorable scripted line to capture the event. This is pure history, the good and the bad.

To understand why this game and this ballpark are so important, here is your field guide to Rickwood: everything you need to know about the Mother Church of Baseball, an honorarium that traces to Chris Fullerton, who spearheaded a renovation to save a decaying ballpark in the 1990s.

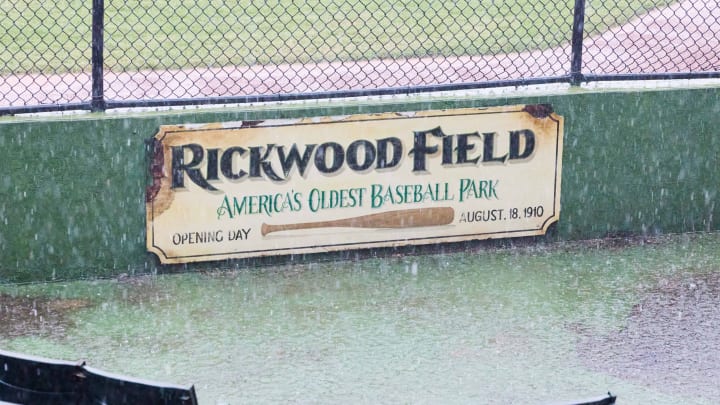

• Rickwood Field opened on Aug. 18, 1910, thanks to Alabama industrialist A.H. “Rick” Woodward, who had purchased the Birmingham Coal Barons after the ’09 season and wanted a ballpark befitting Magic City, so named because of how fast it was booming due to its rich iron and coal resources.

• Woodward threw out the first pitch. The actual first pitch. Woodward, a former catcher at Sewanee College, put himself on the roster, donned a uniform and took the mound for the start of the game between the Barons and Montgomery. His first pitch was called a ball. Woodward argued and was ejected. The Barons won, 3–2, on a walkoff squeeze.

• Rickwood has been America’s oldest ballpark since 1991, with the demolition of Comiskey Park in Chicago. Two years later it was recognized by the National Register of Historic Places.

• More than one-third of the members of the Baseball Hall of Fame have played at Rickwood (107 by one recent count), including Negro League legends Josh Gibson, Charleston, Buck Leonard, Paige, Robinson, Aaron and Mays. Ruth, Ty Cobb, Lou Gehrig, Stan Musial, Mathewson and DiMaggio are the many who played exhibition games at Rickwood.

• MLB spent $5 million renovating Rickwood for this game under the direction of its field czar, Murray Cook.

• Home plate was moved back because it was too far from the stands. The distance from home plate to the backstop is 63 feet. It was 85 feet.

• Moving the field back left much less foul territory. The bullpens had to be moved from the field to beyond the outfield wall.

• The original dugouts were built three feet below grade and accommodated only about 12 players. They were completely rebuilt.

• The field had a two-foot crown to it, or “turtleback” style to accommodate drainage (runoff). Workers took away 5,000 tons of material to install a state-of-the-art drainage system and to regrade the field.

• The chalk outfield foul lines were dug up. Layer upon layer of chalk had accumulated over 100 years—so much chalk that they had to dig down 18 inches to remove it all. The lines are now spray painted on.

• The dirt is from Slippery Rock, Pa., the same place that supplies the dirt for 25 major league parks.

• A Bermuda grass called Tahoma 31 was installed. It’s the same blend used at Dodger Stadium and Angel Stadium.

• The rightfield alley is only 370 feet, which is not to MLB specs. So they built a wall 20 feet high to mitigate the short distance.

• The lights on the iconic light towers do not work. They were built in 1936 by Truscon Steel of Youngstown, Ohio, while Birmingham was climbing out of the Great Depression. Truscon went out of business in the ’70s. Rickwood was one of the first minor league parks with night games. The electronic systems were shot beyond repair and the wiring is not up to code. MLB took out the glass and bulbs (for the safety of fans in the event the lights get struck by foul balls). The field will be lit by portable installments from Musco Lighting, like what was used at the Fort Bragg game.

• During the excavations, workers found a fire pit in right field and pieces of thick glass and intact bottles used for soda in the 1920s.

• The two-story entranceway at the corner of 2nd Avenue West and 12th Street West was added as part of a 1928 renovation. With its colored tilework, gargoyles and barrel roof tiles, it was done in the same Hollywood-inspired Spanish Mission motif as Woodward’s ridgetop estate on Red Mountain.

• The original outfield fence was constructed of wood. The outfield was enormous. Distances were 470 feet to the left field foul, 478 to center, 448 to the right field alley and 335 to right. During the 1928 renovation a 10-foot concrete wall was built where the wooden one stood. But it was so far that home runs were darn near impossible, so an inner wooden fence was built. The concrete wall remains, with distance markers still visible.

• The Black Barons rented the park when the Barons were on the road, though they were barred from using the locker facilities. Black Baron players dressed for games in Black-owned downtown motels.

• During Barons games up until 1963, Black patrons were required to sit in reserved right field bleacher seats just behind the “Arrow Shirts” ad and in an area cordoned off by chicken wire. These were about 500 uncovered seats exposed to the hot sun. During Black Barons games, white patrons would sit in this section.

• Up until 1963, it was illegal for Blacks and whites to play on the same field in Birmingham. According to a local Jim Crow law, “It shall be unlawful for a Negro and a white person to play together, or in company with each other in any game of cards, dice, dominoes, checkers, baseball, softball, football, basketball or similar games.” It became known as The Checkers Rule.

• The Checkers Rule was amended briefly in the spring of 1954 to allow AL and NL teams to play exhibitions at Rickwood. The first integrated baseball game in Birmingham took place April 1, 1954, between the Chicago White Sox and St. Louis Cardinals. Wrote Birmingham News columnist Naylor Stone, “This afternoon will be the first time in our town that white and Negro players have performed at the same time. And when games to follow this Spring are completed, our fans will have seen some of the greatest Negro players.” The next day the Brooklyn Dodgers played the Milwaukee Braves. The starting left fielders were Robinson, then 35 years old, and Aaron, a 20-year-old rookie who would make his major league debut 11 days later.

• The Checkers Rule was restored in full just weeks later. Integrated baseball would not return to Rickwood until 1963.

• Rickwood hosted Klan rallies. A Klan rally there in 1924 drew an estimated crowd of 23,000, including 7,000 robed Klansmen, 1,000 new members who were initiated at the event, a drill team from the Women of the Klan and a Klan band. The rally was capped by an elaborate firework display featuring special Klan pieces.

• Babe Ruth played several times at Rickwood as the New York Yankees played annual exhibition games there in the 1920s.

• Visiting Rickwood in 1921, Ruth, who was 30 pounds overweight after a 54-homer season, said, “You can tell the world I’ll smash out more than 54 homers this year. Every time I swing I try to knock the ball a mile. That’s what the fans want and Babe isn’t going to disappoint them.” He hit 59 that year.

“I can’t help it if I’m fat,” the Babe said while in Birmingham. “I’m certainly trying to work it off and I’ll probably get down to playing weight one of these days. If I don’t—well, I’ll hit homers anyway!”

Ruth went 0-for-4 in a game stopped in the ninth inning when fans threw seat cushions on the field.

• In 1925 Ruth hit three homers in two days, including two in a 4-for-5 day. The next week, Walter Johnson, then 37 and still pitching for the Washington Senators, received an even bigger ovation than Ruth did.

• In 1929 the right field area around Ruth at Rickwood became so packed with kids eager to be around him that the Yankees took him out after the eighth inning, fearful he would be mobbed after the last out.

• What’s the longest home run ever hit at Rickwood? There are four contenders:

- Walt Dropo hit a 467-foot homer over the wooden scoreboard in left. It struck the outer concrete barrier halfway up. The wall has an X marked on it.

- In the first integrated game ever played at Rickwood, Musial hit a 484-foot homer over the roof in right field.

- Reggie Jackson once hit a two-out, walk-off grand slam well over the wall in right center, where the distance was 390 feet.

- How about 147 miles? Ruth hit a home run over the rightfield wall that landed in a passing train car. The ball “did not stop” until the train pulled into Atlanta.

• Mays went to Rickwood Field as a child with his father. He attended high school five miles from Rickwood. Mays played football and basketball in high school, but not baseball because the school did not field a team. He played in the Fairfield Industrial League with his father, Cat. As he turned 17 years old, and still in high school, Willie signed to play with the Black Barons. He could play only home games because his parents did not want him to miss school.

• Mays was still only 17 when he played in the last Negro World Series, in 1948 against the mighty Homestead Grays. The only win for the Black Barons came in Game 3, when Mays stroked a walkoff single.

RELATED: Willie Mays Brought Unrivaled Style to America’s Stuffy Pastime

• Mays played in seven home ballparks. Dunn Field (Trenton), Nicollet Field (Minneapolis), The Polo Grounds (New York), Seals Stadium (San Francisco), Candlestick Park (San Francisco) and Shea Stadium (New York) are all gone. Only Rickwood remains.

• The year 1948 was a momentous year for Rickwood. Not only did the Black Barons reach the Negro World Series, but also the Barons won the Dixie Series. In April of that same year, the Red Sox and Yankees each visited Rickwood for exhibition games, which means in the spring of ’48 Ted Williams, DiMaggio and Mays all played at Rickwood.

• Fifty years ago, on April 2, 1974, Rickwood hosted Hank Aaron Day. Aaron’s Braves played an exhibition game against the Baltimore Orioles. Sitting on 713 home runs, this was the last game Henry played when he trailed Ruth in career home runs. A few days later, on Opening Day, he hit No. 714. Aaron first played at Rickwood in ’52 while with the Indianapolis Clowns.

• The movies Cobb (1994), Soul of the Game (1995) and 42 (2012) were shot at Rickwood. Cobb director Ron Shelton had period ads painted on the walls. Some remain.