JAWS and the 2014 Hall of Fame ballot: Don Mattingly

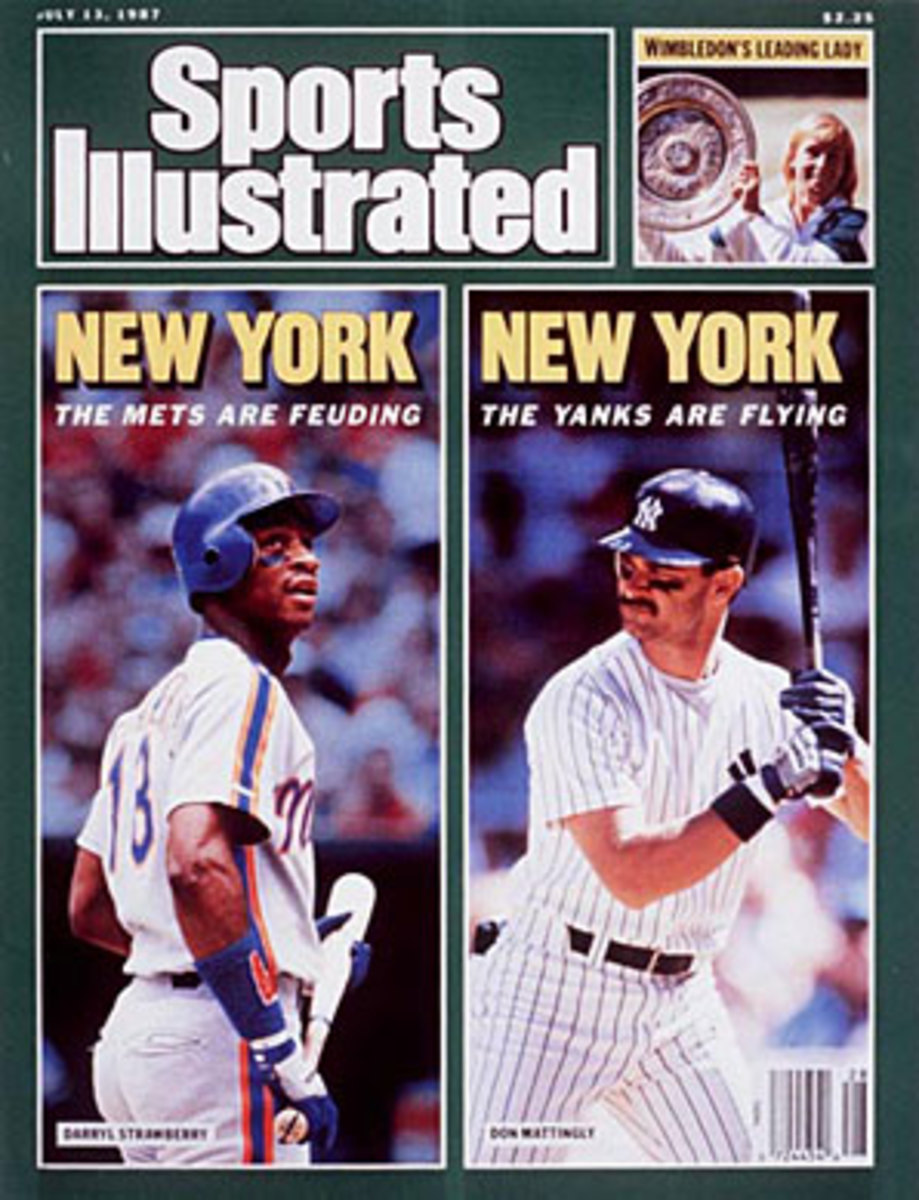

Like fellow New York icon Darryl Strawberry, Don Mattingly was often considered a lock for the Hall of Fame in the 1980s.

The following article is part of my ongoing look at the candidates on the BBWAA 2014 Hall of Fame ballot. Originally written for the 2013 election, it has been updated to reflect last year's voting results as well as additional research and changes in WAR. For a detailed introduction to JAWS, please see here. For the schedule and an explanation of how posts on holdover candidates will be presented, see here.

Beyond his considerable skill against American League pitchers, Don Mattingly was not blessed with the gift of great timing. He was the golden child of the Great Yankees Dark Age that stretched between the Billy Martin/Bob Lemon teams of the late 1970s and early '80s and Joe Torre's end-of-the-millennium dynasty. He debuted in 1982, the year after the Yankees finished a stretch of four World Series appearances in six seasons and retired in 1995, one year before they kicked off a run of six trips to the Fall Classic in eight years.

At his peak, "Donnie Baseball" was both an outstanding hitter and a slick fielder, but a back injury sapped his power, not only shortening that peak but also bringing his career to a premature end at age 34, too soon to enjoy the ensuing celebration in the Bronx.

Mattingly debuted on the 2001 Hall of Fame ballot, the last one before I began my own annual reviews, but it was quickly clear that he didn't have the raw numbers or the support of enough voters to gain entry to Cooperstown. After receiving 28.2 percent of the vote his first time around, he dipped to 20.3 percent in 2002. He's continued to linger below even that mark, coming in with a meager 13.2 percent in 2013. At this point, his candidacy is basically playing out the string, but it deserves a review nonetheless.

Player | Career | Peak | JAWS | H | HR | SB | AVG/OBP/SLG | OPS+ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Don Mattingly | 42.2 | 35.7 | 39.0 | 2153 | 222 | 14 | .307/.358/.471 | 127 |

Avg HOF 1B | 65.7 | 42.3 | 54.0 |

A native of Evansville, Ind., Mattingly was not only naturally talented when it came to baseball, he was ambidextrous. In Little League, he switch-pitched occasionally, throwing three innings righty and three more lefty. By the time of the 1979 draft, he had committed to attend Indiana State University on a scholarship, but the Yankees chose him in the 19th round, and he surprised his family by deciding to sign. Early on during his minor league tenure, his lack of speed and power concerned the Yankees to the point that they considered moving him to second base because of his ability to throw righthanded. Even so, it was abundantly clear that Mattingly could hit, as he topped .300 at every stop in the minors, with good plate discipline and outstanding contact skills even if he never exceeded 10 homers.

Mattingly was just 21 when he made his major league debut on Sept. 8, 1982, but he played sparingly that month, mostly in leftfield. While he broke camp with the Yankees the following spring, he was back at Triple A Columbus by mid-April, as Ken Griffey Sr. held down first base. Recalled in late June, Mattingly spent more time in the outfield than at first and showed little power; in 305 plate appearances, he hit .283/.333/.409 with four homers.

When he took over regular first base duties the following year, he broke out in a big way: .343/.381/.537 with 23 homers and 110 RBIs. He led the league in batting average, hits (207) and doubles(44), ranked fifth in WAR (6.3) while making his first All-Star team and finishing fifth in the AL MVP voting. Thanks to a whopping 145 RBIs the following year, he earned AL MVP honors for a season that actually wasn't radically different: .324/.371/.567 with 35 homers, 48 doubles and 6.4 WAR, again fifth in the league. He also took home the first of nine Gold Gloves that he'd win in a 10-year span. The Yankees won 97 games that year, the most they ever won during his 14-year career, but they finished two games behind the Blue Jays in the AL East standings.

In 1986, Mattingly racked up a league-leading 238 hits, 53 doubles and 31 homers en route to a monster .352/.394/.573 line; his slugging percentage led the league, his batting average ranked second to Wade Boggs' .357 and his 7.2 WAR placed third behind Boggs (7.9) and Jesse Barfield (7.6). His numbers took a dip the following year when he missed nearly three weeks due to a back injury suffered while wrestling teammate Bob Shirley in the clubhouse. Though he was diagnosed with two protruding discs, he actually hit better after returning (.336/.371/.601 with 24 homers) than before (.311/.390/.485 with six homers).

In the coming years, Mattingly would battle back problems with increasing frequency. He dipped from 30 homers and a .559 slugging percentage in 1987 to 18 and .462 in 1988, and while the MLB-wide dropoff in slugging percentage after an uncharacteristically homer-saturated year was part of that — from .415 to .378 — it was a sign of things to come. After rebounding to 23 homers and a .303/.351/.477 showing in 1989, his last season as an All-Star, he would never reach 20 or slug even .450 again, nor would he have a season worth more than 2.7 WAR.

By that point, Mattingly was battling George Steinbrenner as much as his own back. When he set a record with an arbitration award of $1.975 million in 1987, the New York owner quipped, "The monkey is clearly on his back. He has to deliver a championship like Reggie Jackson did. [Mattingly's] like all the rest of 'em now. He can't play little Jack Armstrong of Evansville, Indiana, anymore." Furthermore, Steinbrenner called him "the most unproductive .300 hitter in baseball," a ridiculous thing to say in an industry where RBI totals were viewed as productivity. Nobody was within 50 RBIs of Mattingly's 1984-87 total at the time Steinbrenner said that.

When Mattingly responded by talking about how many unhappy players the team had, Steinbrenner pressed for an apology behind the scenes and put him on the trading block. At one point Mattingly was rumored to be part of a deal that would have sent him to the Giants for Will Clark. Eventually, he buried the hatchet and remained a Yankee, signing a five-year, $19.3 million extension in April 1990.

Which alas, didn't work out all that well for the franchise. Mattingly hit just 14 homers and slugged .370 over the next two seasons combined, missing seven weeks of the 1990 season due to further back troubles. He rebounded somewhat in 1992 and '93, reaching double digits in homers in each year, but he was never again a true offensive force. After hitting .327/.372/.530 and averaging 27 homers and 5.5 WAR from 1984-89 — making him the seventh-most valuable position player in the game during that span — he slipped to .286/.345/.405 with an average of 10 homers and 1.5 WAR over his final six seasons.

In a bittersweet coda to his career, the Yankees finally reached the playoffs on his watch in 1995; he hit a sizzling.417/.440/.708 during the Division Series against the Mariners, but New York lost an agonizing five-game series. Mattingly retired after the season, while in 1996 his replacement, Tino Martinez, helped power the Yankees to their first world championship since 1978.

Given the emphasis voters place on career totals and milestones, it is almost impossible for a player to make the Hall of Fame if his career ends before age 35. Since the end of World War II, pitchers Sandy Koufax, Don Drysdale and Catfish Hunter have been elected by the BBWAA under such circumstances, and among position players, Lou Boudreau stands as the only one. Kirby Puckett and Larry Doby played through their age-35 seasons before calling it quits, while Ron Santo and George Kell, who last played at age 34, didn't gain entry until the Veterans Committee took up their cases. Unlike Puckett or Koufax, Mattingly doesn't even have the advantage of walking away when he was still at his peak; his play had been subpar for more than half a decade when he left.

Thus it's not surprising that Mattingly falls far short on the JAWS front, ranking 35th among first basemen, above only two Hall of Famers: "Sunny Jim" Bottomley and George "High Pockets" Kelly. He has received little support from the voters, falling below 25 percent in his second year, below 20 percent in his third and ranging between 9.9 percent (2007) and 17.8 percent (2012) since with no clear pattern to his support beyond its lack. While he may remain above the five percent minimum for his final two cycles, that's about the best he can hope for.

Still, Mattingly's case may not be entirely closed when it comes to Cooperstown. While he has fallen into his share of tactical traps as a manager in three years at the helm of the Dodgers, he has shown some degree of promise in guiding the team to a .535 winning percentage amid the team's bankruptcy, sale and a seemingly endless barrage of injuries and other distractions — including his most recent wavering on a return. In 2013, Los Angeles came within two wins of a trip to the World Series, and it appears to be armed to challenge again. Like mentor Joe Torre, who was just elected to the Hall of Fame by the Expansion Era committee this week, Mattingly could augment his case considerably via the dugout, though he probably needs his own Don Zimmer to avoid future pitfalls.