JAWS and the 2014 Hall of Fame ballot: Most overlooked at every position

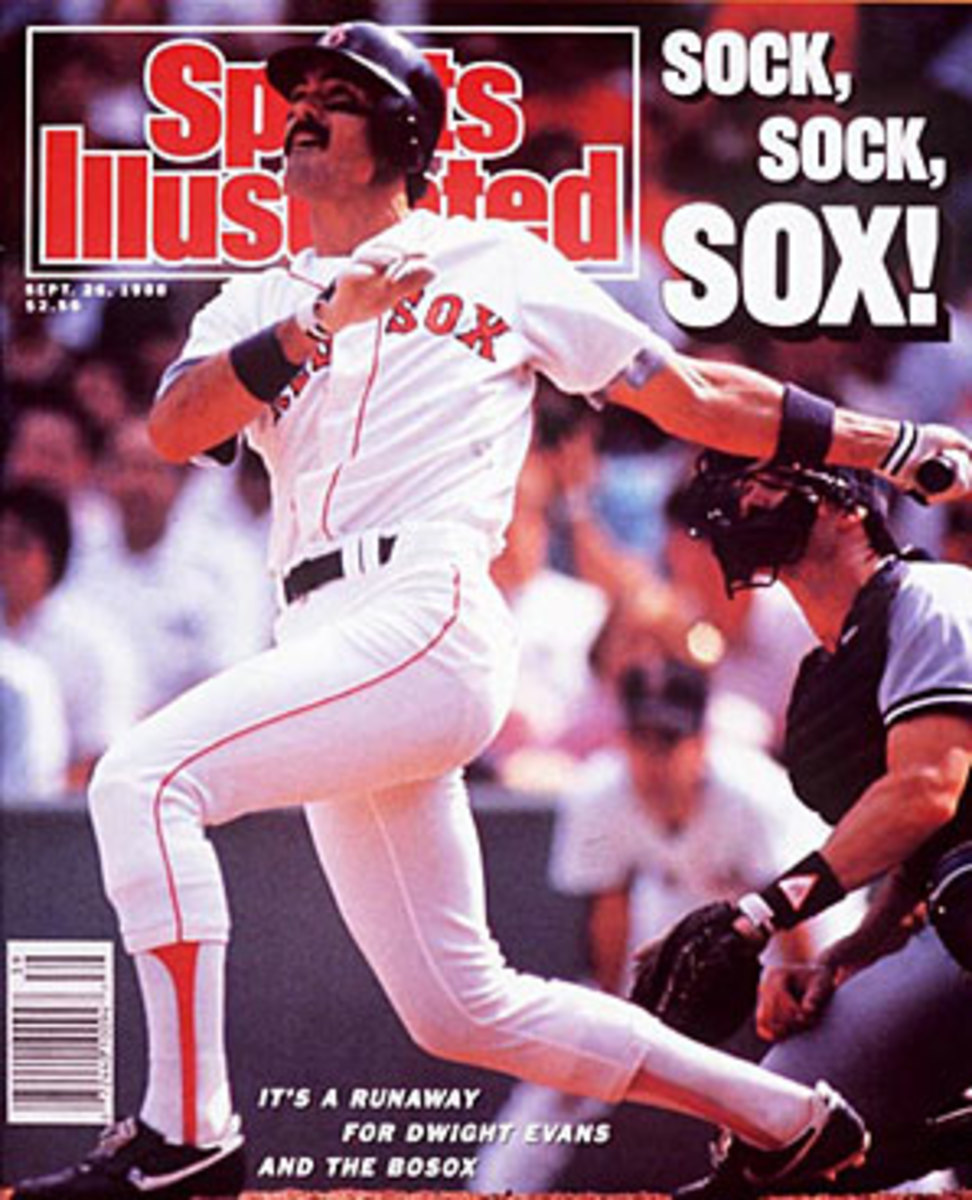

Dwight Evans made three All-Star teams and won eight Gold Gloves in his 20-year career, 19 with the Red Sox. (John Biever/SI)

The following article is part of my ongoing look at the candidates on the BBWAA 2014 Hall of Fame ballot. For a detailed introduction to JAWS, please see here. For the breakdowns of each candidate and to read the previous articles in the series, see here.

Normally at this time of year, I tend to revisit an idea inspired by Bill James, identifying the top players at each position who remain outside the Hall of Fame. The concept is a nod to James’ systematic Keltner Test, named for former Indians third baseman Ken Keltner, a seven-time All-Star best known for his defensive work in helping to end Joe DiMaggio’s 56-game hitting streak in 1941. James’ test is a set of 15 questions that can be used to frame a player’s case for Cooperstown. One of the most important (emphasis in original) is: “Is he the best player at his position who is eligible for the Hall of Fame but not in?”

The answers to those questions form what I refer to as the Keltner All-Stars, the best player outside the Hall at each position. However, because of the current ballot backlog those answers haven't changed much since I addressed the topic a year ago. Mike Piazza, Jeff Bagwell, Alan Trammell, Barry Bonds, Larry Walker and Roger Clemens remain on the ballot, eligible for election but likely to fall short this year, either by a little or a lot.

Given that by now you've heard my spiel on each, I figured it would be more illuminating to dig a bit deeper and highlight the best eligible player (retired for at least five years, and not banned for life) at each position who's not on the current ballot, and thus likely to remain in limbo for at least a few more years. So let's take a trip around the diamond.

Catcher (52.4 Career WAR/33.8 Peak WAR/43.1 JAWS): Thurman Munson (45.9/36.9/41.4)

Munson accumulated a boatload of Cooperstown-worthy credentials during an 11-year career (1969-79) that was tragically cut short by his death in a plane crash. He won the 1970 AL Rookie of the Year award, the 1976 AL MVP award and three Gold Gloves while earning All-Star honors seven times. He did all of this while leading the Yankees out of their 1965-75 Dark Age; they won three straight pennants from 1976-78 and back-to-back World Series titles in the latter two years. What's more, he hit a sizzling .357/.378/.496 in 135 postseason plate appearances.

Munson's untimely death leaves him understandably short on the career JAWS standard, but even so, he surpasses the peak standard by a full three wins. That's mainly due to defense; he was 34 runs above average for his career according to Total Zone. While his bat was in decline over his final two seasons (.293/.335/.373, down from .309/.352/.441 from 1975 through 1977), he was still getting on base enough to provide above-average offense for the position.

Given all of that, I think it's reasonable to consider him for Cooperstown. I tabbed him here instead of the longer-lasting Ted Simmons (50.2/34.7/42.5), who's two rungs above him in the overall JAWS catcher rankings (11th versus 13th) and who was just passed up for election by the Expansion Era Committee despite strong credentials himself. Munson has been passed over by the VC several times, but he deserves another look.

First Base (65.7/42.3/54.0): Keith Hernandez (60.1/41.0/50.6)

Hernandez didn't have the power that we normally associate with modern first basemen, hitting just 162 homers in his 17-year career from 1974-90. Nonetheless, he was an on-base machine (.296/.384/436 career) who not only won a batting title but had seven years among the league's top three in OBP because he was also good for 80-plus walks per year. On top of that, he was an elite defender according to both traditional and advanced measures; he won 11 straight Gold Gloves from 1978-88, and his 117 runs above average according to Total Zone ranks second among post-1900 first basemen.

In all, Hernandez ranked among the league's top five in WAR four times and among the top 10 in six seasons; when he shared the 1979 NL MVP award with Willie Stargell, he bested him in WAR 7.5 to 2.5. He won world championships with the Cardinals in 1982 and the Mets in 1986. Because his career ended at age 36, after three years of playing less than 100 games, neither his traditional nor advanced stats measure up; he's 18th at the position in JAWS.

Hernandez never got the time of day from BBWAA voters, topping out at 10.8 percent in nine years on the ballot; his early career cocaine problems probably didn't help. He'd probably fare better in front of a more modern electorate given an increased appreciation for just how good his glovework was. I'd be surprised if he doesn't gain entry via a VC-style committee sometime over the next decade or so.

Second Base (69.5/44.5/57.0): Bobby Grich (71.0/46.3/58.6)

For stat-minded fans of a certain age, Grich’s absence from Cooperstown ranks among the great injustices of the universe, making him the keystone equivalent of long-neglected, belatedly enshrined third baseman Ron Santo. From 1970 through 1986, Grich combined good power with excellent plate discipline and outstanding defense (+71 runs) while playing on five division-winning teams in Baltimore and Anaheim. He earned All-Star honors six times, won four Gold Gloves and led the AL in homers and slugging percentage during the strike-shortened 1981 season.

Unfortunately, injuries — including a herniated disc caused by carrying an air conditioner up a stairway — cost him about a season’s worth of playing time and forced him into retirement after his age-37 season. Between that and his 13 percent walk rate (en route to a .371 on-base percentage), he finished his career with just 1,833 hits, a total that appears to be an impediment to election, given that no player from the post-1960 expansion era with fewer than 2,000 hits has been elected. Even so, he ranks seventh at the position in JAWS, above the standard on all three fronts.

The injustice took place in 1992, when Grich debuted on the BBWAA ballot and received just 2.6 percent of the vote, less than the 5.0 percent needed to stick around. Since then, he has yet to appear on a Veterans Committee ballot, and he was bypassed for the 2014 Expansion Era ballot. So was another lamentably one-and-done second base contemporary, Lou Whitaker (74.8/37.8/56.3), whose credentials aren't quite as strong.

Third base (67.4/42.7/55.0): Graig Nettles (68.0/42.2/55.1)

Like Grich, Nettles is another holdover from last year's team, and another contemporary as well. He spent the bulk of his 22-year career (1967-88) in the shadow of fellow third baseman Brooks Robinson, so despite elite defense (+134 runs), he won just two Gold Gloves. Get a highlight film of Game 3 of the 1978 World Series and you'll see the impact one infielder can have on a game; his leaping stops kept the Dodgers at bay and turned the series in the Yankees' favor.

Though he didn't hit for high averages, Nettles had plenty of power (390 career home runs) and a decent walk rate. He earned All-star honors six times and played on five pennant-winning teams for the Yankees and Padres, with additional stops elsewhere. Thanks to his glovework, he led his league in WAR twice (1971 and '76) and ranked in the top 10 five times. Overall, he ranks 12th in JAWS, within a few runs in either direction of all three standards.

Nettles lasted just four years on the BBWAA ballot, peaking at 8.3 percent, but particularly given the shortage of third basemen in the Hall (just 13, compared to as many as 24 in rightfield), he has a solid case for induction someday.

Shortstop (66.7/42.8/54.7): Bill Dahlen (70.3/44.6/57.5)

Dahlen spent 21 years of the Deadball Eria (1891-1911) with four different National League teams, three of whom played under different nicknames than they carry now: the Chicago Colts (briefly named the Orphans, and now the Cubs), Brooklyn Superbas (now Dodgers), New York Giants and Boston Doves (now Braves). He was a heady player known more for his fielding, his temper and his carousing than his hitting, but he was quite good at the plate for the day, racking up 2,461 hits with a 110 OPS+. In the 2000 New Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract, Dahlen ranked 21st among shortstops, with James calling him "a high-living, hard-drinking player with a great fondness for horse races," who would regularly get ejected so as to hit the track.

Dahlen never led his league in WAR, but despite his detours to play the ponies, he ranked in the top 10 eight times and in the top five six times. His career WAR total ranks seventh among shortstops and is above the Hall average at the position. His peak score, which ranks 21st, is slightly below, but his overall JAWS ranks 10th and is above the standard. It's also above the scores of Hall of Fames Barry Larkin, Bobby Wallace, Lou Boudreau, Joe Cronin, Pee Wee Reese and eight other enshrined shortstops, and it's also ahead of Derek Jeter and Alan Trammell.

Dahlen fell short on the 2008 Veterans Committee and 2013 Pre-Integration Era Committee votes, but he was a much stronger candidate than the elected Deacon White.

Leftfield (65.0/41.5/53.2): Sherry Magee (59.1/38.5/48.8)

With Barry Bonds (first in JAWS among leftfielders) and Tim Raines (eighth) both on the ballot but not getting elected this year, Pete Rose (fifth) serving a lifetime ban for gambling and Manny Ramirez (10th) waiting out his five-year retirement before being pelted with rotten eggs by PED-minded voters, the best available leftfielder who is eligible for consideration here is an obscure one to modern baseball fans.

Magee was a Deadlball Era star who spent the first 11 years of his 16-year career (1904-19) with the Phillies, hitting .291/.364/.427 for a 137 OPS+. He led the NL in WAR in 1910 and cracked the top 10 seven times; he won the slash-stat Triple Crown in that 1910 season for a .331/.445/.507 line, numbers he would never approach again save for a .509 slugging percentage in 1914. He ranks 14th at the position in JAWS, and while he doesn't surpass any of the JAWS standards, he outdoes 10 of the 19 enshrined leftfielders, including Joe Medwick, Stargell, Zack Wheat and Ralph Kiner (ranked 15th-18th), not to mention Jim Rice (27th)

Centerfield (70.4/44.0/57.2): Kenny Lofton (68.1/43.2/55.7)

Lofton was a stellar leadoff hitter with a career .372 on-base percentage, six All-Star appearances, five Gold Gloves and 11 trips to the postseason (where, alas, he hit just .247/.315/.352 in 438 PA). He ranks ninth among centerfielders in JAWS, just a bit below the standards on all three fronts. A first-time eligible candidate last year, the well-traveled Lofton got lost in the shuffle; I couldn't find room for him on my virtual ballot, and I wasn't alone, for he fell off after receiving just 3.2 percent of the vote. He deserved far better than that.

Rightfield (73.3/42.9/58.1): Dwight Evans (66.7/37.0/51.8)

Evans spent 19 of his 20 years in the majors (1972-1991) with the Red Sox, the bulk of them in the shadow of Hall of Famers Carl Yastrzemski and Rice, not to mention 1975 AL Rookie of the Year and MVP Fred Lynn. Evans was a stud in his own right, however. He had a career .272/.370/.470/127 OPS+ line with 2,446 hits and 385 homers, though he made just three All-Star teams. Because he was an excellent defender (+82 runs, not to mention eight Gold Gloves), he was far more valuable than Rice (47.2/36.1/41.7), though he only cracked the AL top 10 in WAR twice, leading it in the strike-shortened 1981 season.

Back when JAWS was based on Baseball Prospectus' version of Wins Above Replacement Player, Evans was above the bar, but that's no longer the case. Still, it's a shame that he fell off the ballot after just three years with a high of 10.4 percent of the vote.

Starting Pitcher (72.6/50.2/61.4): Wes Ferrell (61.6/54.9/58.3)

If you exclude the pitchers on this year's ballot, the ones who will soon be there and those whose careers didn't cross into the 20th century, the top-ranking pitcher outside the Hall according to JAWS is Ferrell. He sits at number 39, well ahead of the peak standard but short on career due to arm troubles that turned him into a palooka by his age-30 season and knocked him out of the majors by age 33. Still, the younger brother of Hall of Fame catcher Rick Ferrell is arguably the one more qualified to be enshrined.

In his heyday with the Indians (1927-33), Ferrell was regarded as the equal of the great Lefty Grove, and research has shown that at his peak he faced much tougher competition than Grove, who consistently feasted on the league’s lesser teams. From 1929 through 1936, Ferrell won 161 games with a 3.72 ERA, which in that high-scoring era was still 28 percent better than the park-adjusted league average. He finished second in the AL MVP vote in 1935 on the heels of a monster 11.0-WAR season in which he won 25 games while pitching 322 1/3 innings of 3.52 ERA ball (34 percent better than league average) and hit an insane .347/.427/.533 with seven home runs in 179 plate appearances as a pitcher.

On that note, Ferrell was an outstanding hitter who batted .280/.351/.446 with 38 homers for his career (his brother hit just 28, and had lower a batting average and slugging percentage), numbers that chip away at the fact that his 4.04 ERA would be the Hall’s high were he to gain entry. The 12.7 WAR he generated with the bat — including over 150 pinch-hitting appearances, and a brief stint in the outfield, is about 11 wins more than the average Hall of Fame hurler. He was on last year's Pre-Integration Era ballot, but he fell short; his case figures to be taken up again the next time around, simply on the strength of that peak.

Relief Pitcher (40.6/28.2/34.4): Bobby Shantz (34.8/25.1/29.9)