JAWS and the 2014 Hall of Fame ballot: The All One-and-Done Team

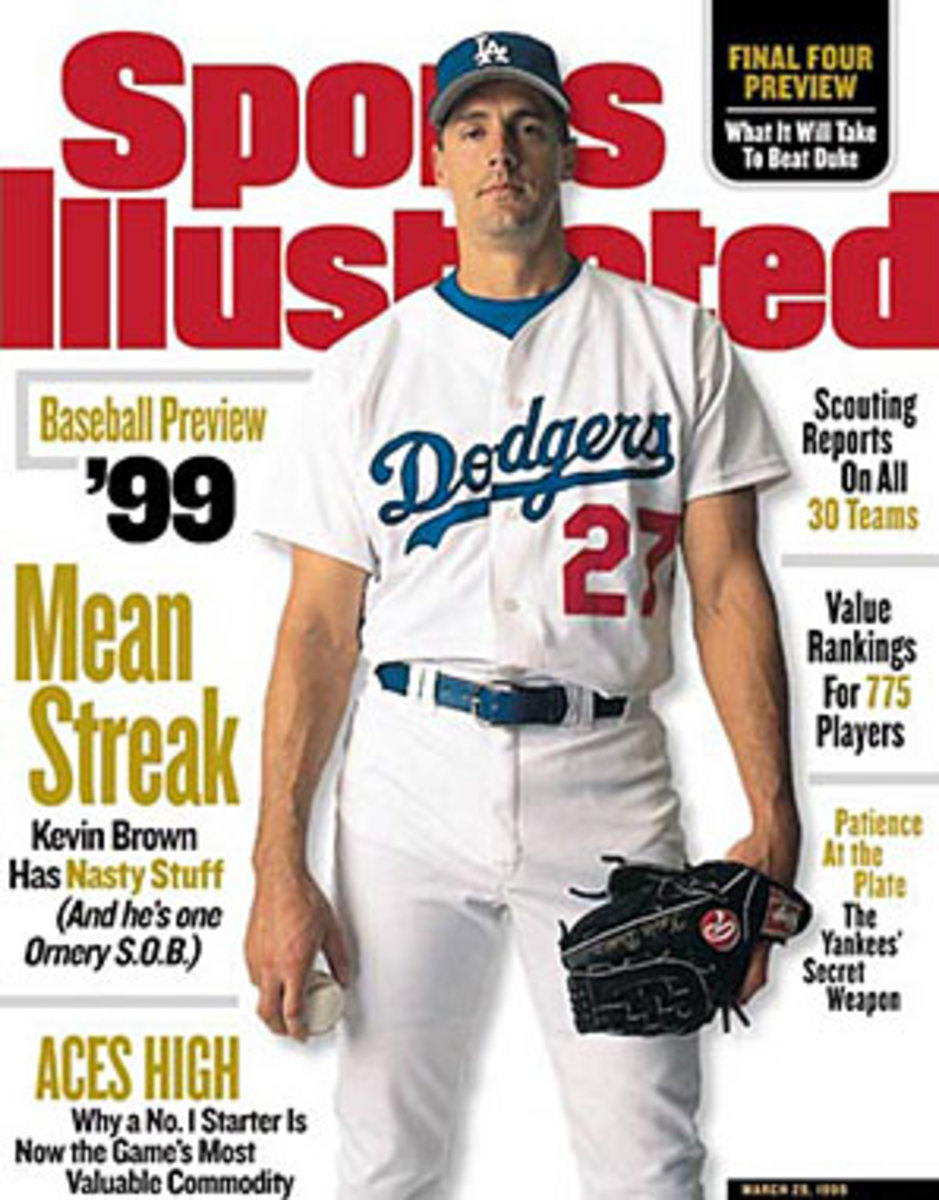

Kevin Brown, baseball's first $100 million man, won 211 games in his 19 seasons. (Walter Iooss Jr./SI)

The following article is part of my ongoing look at the candidates on the BBWAA 2014 Hall of Fame ballot. For a detailed introduction to JAWS, please see here. For the breakdowns of each candidate and to read the previous articles in the series, see here.

One fear regarding the crowded Hall of Fame slate and the limit of 10 votes per ballot is that worthy first-time candidates might not even get a second look from voters. That's what happened to Kenny Lofton last year; the six-time All-Star, owner of 2,428 hits, 626 steals and a lifetime .372 on-base percentage received just 3.2 percent of the vote. By failing to garner even five percent, he fell off the ballot. Not only is he no longer eligible for election by the BBWAA, but under current rules he'll have to wait until at least 2028 for consideration by the Veterans Committee.

The five percent rule didn't even come about until 1979; prior to that, candidates remained eligible to receive votes, though voters seldom paid them any mind. For example, in one of the most pathetic examples of BBWAA ignorance, Larry Doby — who broke the color barrier in the American League on July 5, 1947 — received just 2.3 percent of the vote in 1966, his first year on the ballot, and then 3.4 percent the following year. He didn't receive any BBWAA votes after that, and it took until 1998 before the Veterans Committee elected him.

In 1980, the rule was revised so that candidates had to receive five percent in one of the previous two elections, though in 1985, it was changed back to five percent in the previous election. At that point, a handful of players who had previously gone one-and-done had their eligibility restored. From among that group, longtime Cubs third baseman Ron Santo eventually gained election, but it came via the Veterans Committee in December 2011, a year after his death.

Via the 133 ballots publicly revealed thus far, two candidates whom Hall of Fame researcher Bill Deane predicted would finish in single digits, Mike Mussina and Jeff Kent, appear to be safe from single-ballot ignominy; the former is at 31.6percent and the latter at 14.3 percent, so both have significant cushions when it comes to the as-yet-unrevealed ballots.

That's great news, if only because it means they won't join this lineup, which highlights the best of the one-and-done players using JAWS. Because there's some crossover with my previous post on the most overlooked players at each position, I'll highlight a different candidate at those positions, including centerfield, where Lofton would otherwise reign. These players may not belong in the Hall of Fame but they certainly should have gotten longer looks from the voters.

Catcher (52.4 Career WAR/33.8 Peak WAR/43.1 JAWS): Ted Simmons (50.2/34.7/42.5)

As I noted in conjunction with his Expansion Era Committee ballot appearance, Simmons was an outstanding catcher who earned All-Star honors six times in his 13 seasons with St. Louis (1968-80), though his career went downhill quickly upon being traded to Milwaukee and shifting to DH and the infield corners. He ranked among the league’s top 10 in batting average six times, was in the top 10 in on-base or slugging percentage nine times and was among the top 10 in position player WAR five times. For his career, he hit .298/.366/.459 with 2,472 hits and 248 homers, good for a 118 OPS+.

Alas, Simmons received just 3.7 percent of the vote in 1994, his lone year on the BBWAA ballot. The showing may have had something to do with lingering resentment over the fact that in 1972, in the wake of former teammate Curt Flood’s challenge to the Reserve Clause, he became the first playing holdout in baseball history, playing well into the season without a signed contract before the Cardinalsgave in to his demands. Particularly considering that he ranks ninth at the position in terms of JAWS — ahead of the peak standard and just six runs shy of the overall standard — he deserved better not only there but in this year's Expansion Era election.

First Base (65.7/42.3/54.0): John Olerud (58.0/38.8/48.4)

Though not blessed with tremendous power, Olerud was a very patient hitter with a sweet swing, a keen batting eye and defensive skill at first base. Due to a brain aneurysm he suffered in college, he wore a batting helmet onto the field for protection while playing defense — a distinction that became the subject of an amusing but apocryphal Rickey Henderson anecdote.

Olerud hit .295/.398/.465 in his 17-year career with the Jays, Mets, Mariners, Yankees and Red Sox, serving as Toronto's starting first baseman during its back-to-back World Series wins; in the latter, season, he led the American League in batting average and OBP as he hit .363/.473/.599 with 54 doubles (also a league high), 24 homers and 114 walks. He made another run at a batting title with the Mets in 1998, finishing second in the National League in both on-base and slugging percentages while hitting .354/.447/.551. Because he wasn't blasting 40 homers, he struggled to stand out in his time, so despite five seasons with at least 5.0 WAR, he earned All-Star honors just twice, though he did win three Gold Gloves.

Retiring at age 37 left him with 2,239 hits and 255 homers, numbers that caused voters to completely overlook him; he garnered just four votes (0.7 percent) on the 2011 ballot. He's short on all three JAWS fronts, but does rank 20th at the position, ahead of eight enshrined first basemen including Tony Perez and Orlando Cepeda.

Second Base (69.5/44.5/57.0): Lou Whitaker (74.8/37.8/56.3)

Having highlighted Bobby Grich (71.0/46.3/58.6 but just 2.6 percent of the vote in 1992) last time around, I turn my attention here to Whitaker, who spent all of his 19 years (1977-95) with Detroit and partnered with shortstop Alan Trammell for the longest running double-play combo in the game's history. The two even debuted in the same Sept. 9, 1977 game. They were part of the backbone of the 1984 World Series-winning Tigers and the 1987 AL East champions, and as Whitaker himself recently pointed out, they were a big part of the reason Jack Morris has anything close to a Hall of Fame case.

Whitaker won AL Rookie of the Year honors in 1978, was a five-time All-Star and a three-time Gold Glove winner. He racked up 2,369 hits and 244 homers while hitting .276/.363/.426 (117 OPS+) for his career. Yet he received just 2.9 percent of the vote in 2001, and like Grich, hasn't even received a sniff from the Veterans or Expansion Era committees. He ranks 11th at the position in JAWS, ahead of the career standard by more than five wins, and within one point of the overall standard.

Third base (67.4/42.7/55.0): Buddy Bell (65.9/40.2/53.1)

No position has been more mistreated by the BBWAA than third base. Pie Traynor was the only one the writers elected through 1977, and that came way back in 1948. When Eddie Mathews and his 512 homers were elected in 1978, it marked his fifth go-round on the ballot; today he ranks second at the position in JAWS (96.2/54.2/75.2).

Among those who were quickly disposed of include Ken Boyer, Ron Santo, Ron Cey and Darrell Evans. Boyer was an MVP and a seven-time All-Star with a score near the standard (62.9/46.4/54.6), but he didn't receive even five percent of the vote in his first five tries (1975-79). He fell off when the five percent rule went into effect and never got higher than 25.5 percent once his eligibility was restored in 1985. Santo, who ranks sixth at the position — well, you've heard his tale of woe already. Cey, a six-time All-Star with 316 homers and a part of the Longest Running Infield that anchored four Dodger pennant winners, fell off after receiving just 1.9 percent in 1993. And Evans, who hit 414 homers, received only 1.7 percent of the vote in 1995.

Those last two have to stand behind Bell, who tied Evans at 1.7 percent in 1995 and who ranks 15th at the position in JAWS, a bit short on all three fronts but no slouch. Though lacking the power of the aforementioned hot cornermen, he hit .279/.341/.406 for a 109 OPS+, with 2,514 hits and 201 homers. He was even better defensively; his 167 runs above average (via Total Zone) ranks fourth behind Brooks Robinson, Adrian Beltre and Scott Rolen, which is how he managed to win six Gold Gloves despite playing in the same league as Graig Nettles (+134 but a stronger case on both JAWS and traditional fronts).

Shortstop (66.7/42.8/54.7): Bert Campaneris (53.3/36.7/45.0)

Campaneris spent the first 13 seasons (1964-76) of his 19-year career with the A's, covering both their lousy years in Kansas City and their three straight World Series wins in Oakland. A slick fielder (+71 Total Zone for his career), he never won a Gold Glove, mainly because Luis Aparicio and Mark Belanger combined to win 17 out of 21 from 1958 through 1978. Campaneris wasn't much of a hitter (.259/.311/.342 for an 89 OPS+) but his offense was on par with the expectations of the day, and he did have speed; he led the AL in steals six times in an eight-year span from 1965-72 and racked up 649 steals for his career, good for 14th all-time. That package helped him make six All-Star appearances, three (1973-75) as a starter.

Thanks to his defense, Campaneris ranked in the league's top 10 in WAR among position players four times from 1968-74. He ranks 20th in JAWS at the position, ahead of the enshrined Aparicio (55.7/32.7/44.2) and six other Hall of Fame shortstops. Still, he received just 3.1 percent of the vote in his lone appearance in 1989.

Leftfield (65.0/41.5/53.2): Jose Cruz (54.3/36.2/45.3)

A tremendously underrated player who was by far the best of three brothers to make the major leagues, Cruz spent 13 of his 19 years (1975-87) with the Astros, helping to put them on the map with three playoff appearances in 1980, '81 and '86. He didn't have a ton of power, never reaching 20 homers and finishing with just 165 in his career to go with 2,251 hits, but he did hit .292/.359/.429 during his Houston days, which once properly translated for the run-suppressing Astrodome was good for a 125 OPS+.

Cruz made just two All-Star teams during his career, a low total given that he accumulated seven seasons of at least 4.0 WAR across a nine-year span (1976-84) and ranked in the league's top 10 three times. His 41.6 WAR during that timeframe ranked eighth in the majors, topped by five Hall of Famers and outdoing several others; he's nestled between Andre Dawson and Dave Winfield in those rankings. Overall, he's 21st among leftfielders all-time in JAWS, six spots above the enshrined Jim Rice (47.2/36/41.7). The underappreciation of Cruz continued when he received all of two votes (0.4 percent) on the 1994 Hall of Fame ballot.

Centerfield (70.4/44.0/57.2): Jimmy Wynn (55.7/43.3/49.5)

"The Toy Cannon" was a 5-foot-10 sparkplug with power, outstanding control of the strike zone and good defense, a player whom Bill James compared to early-career teammate Joe Morgan in The New Bill James Historical Abstract while ranking Wynn 10th all-time among centerfielders. He spent the first 11 years of his career (1963-73) playing in the Astrodome, the game's toughest pitchers' park, then another two in Dodger Stadium, which wasn't much easier. His career line of .250/.366/.436 doesn't look tremendously impressive, but it translated to a 129 OPS+.

Because of his low batting averages and high walk totals, Wynn was not given proper due in his time — he made just three All-Star teams — but he did reach 20 homers eight times and 30 homers three times. He also walked more than 100 times in a season six times, leading the league twice. In 1969, he had more walks (148) than hits (133) to go with his 33 homers en route to a .269/.436/.507 line, a 166 OPS and 7.1 WAR, one of three seven-win seasons and four in his league's top 10.

Alas, shoulder woes cut his career short after a combined .198/.352/.328 showing in 1976-77, his age 34-35 seasons, so he finished with just 291 homers and 1,665 hits along with his 1,224 walks. He was shut out entirely when he appeared on the BBWAA ballot in 1983, yet another player whose broad skill set was underappreciated by voters. He ranks 16th among centerfielders in JAWS, with a significantly higher peak than 15th ranked Willie Davis (60.7/38.9/49.8), a fielding whiz and staple of three pennant-winning Dodgers teams.

Rightfield (73.3/42.9/58.1): Reggie Smith (66.7/37.0/51.8)

"The Other Reggie" during the time of Jackson, Smith was a switch hitter with power (314 career homers), patience (11 percent walk rate) and a rifle arm. He was also a seven-time All-Star who served as the Red Sox centerfielder during the "Impossible Dream" season of 1967 and reached his height as a member of the late-1970s Dodgers after a brief but productive stay in St. Louis.

Smith placed in the league's top 10 in on-base percentage four times, leading the NL with a .427 mark in 1977, and in the top 10 in slugging percentage eight times, including four years where he was either second or third. He reached the 20-homer plateau eight times, and the 30-homer plateau twice, with the 1971 Red Sox and the 1977 Dodgers. He racked up five seasons of at least 5.0 WAR and another four of at least 4.0; via JAWS he ranks 16th among rightfielders, just below Tony Gwynn and Dwight Evans, and above Sammy Sosa, Ichiro Suzuki and Winfield.

Injuries got the better of Smith late in his career; he made just 1,074 plate appearances from 1979-82, his age 34-37 seasons, then split for a disastrous stint in Japan where he battled with umps, brawled with fans, got hurt frequently and earned the nicknames "Giant Human Fan" and "Million Dollar Bench-Warmer" despite productivity in limited doses. Had he stayed healthy on this side of the Pacific Ocean, he'd have ended with far more than 2,020 career hits and 8,050 plate appearances, just above the thresholds where voters tend to disregard any post-1960 expansion player. As it was, he received just 0.7 percent of the vote on the 1988 ballot and has never gotten a sniff from the Veterans Committee.

Starting Pitcher (72.6/50.2/61.4): Kevin Brown (68.3/45.4/56.9)

A wiry, ornery sinkerballer who spent 19 years in the majors pitching for six teams, Brown was the ace of two pennant winners, the 1997 Marlins and 1998 Padres. He earned All-Star honors six times, and while he never won a Cy Young award, he placed in the top three in both 1996 and '98. He led the NL in ERA and WAR twice, finishing in the top five in the former category six times. From 1996 to 2000, he ranked in the league's top three in WAR every year, topping 7.0 WAR four times; over that five-year span, only Pedro Martinez outdid his 37.0 WAR.

Outside of that concentrated peak, Brown is mostly remembered for becoming baseball's first $100 million dollar player, signing a seven-year, $105-million deal with the Dodgers in December 1998, at age 34. The contract painted a target on his back, and neither the deal nor the pitcher aged well. After a strong first two years, he made only 96 starts over the next five, topping 30 just once due to back and elbow woes, both of which required surgery. After a solid comeback in 2003, the best of that late stretch, he was traded to the Yankees, but was limited to 22 starts in 2004 by further back troubles, broke his non-pitching hand punching a clubhouse wall and gained further infamy with a terrible showing in the ALCS against Boston, where he was tagged for nine runs in 3 1/3 innings over two starts. The second of those came in Game 7, helping the Red Sox to complete their miracle comeback from a 3-games-to-0 deficit.

Brown's career 3.28 ERA and 127 ERA+ are impressive given the period that he pitched, but because he finished with just 211 wins and a middling record (5-5, 4.19 ERA) in postseason play, he never got a second look from the BBWAA voters. He fell off after managing just 2.1 percent on the 2011 ballot.

Relief Pitcher (40.6/28.2/34.4): John Hiller (30.9/26.9/28.9)

The southpaw Hiller spent all of his 15-year career (1965-80) with the Tigers, transitioning from a swingman role to a fireman-type relief ace after missing all of the 1971 season and part of 1972 due to a heart attack. He recovered to enjoy a monster 1973, throwing 125 1/3 innings of 1.44 ERA ball, leading the league with 65 appearances and 38 saves and finishing with 8.1 WAR, the league's second-highest total among pitchers.