The Baltimore Orioles Have a ‘Type’

Every so often, the Baltimore Orioles call up a prospect, and catcher James McCann does a double take.

There he is again, he thinks.

“It's almost like, in the dating world, when you look at all the people you’ve dated, they all have similar characteristics,” he says. “You're like, yeah, I guess I have a type. I guess the Orioles have a type.”

For the most part, that means a young, athletic position player who controls the strike zone well and hits for some power. That combination is working out well for the Orioles, whose 49–25 record is tied for second best in the sport. But as many fans—and the players themselves—have noticed, those traits have recently manifested themselves in a few young men who bear a striking resemblance to one another.

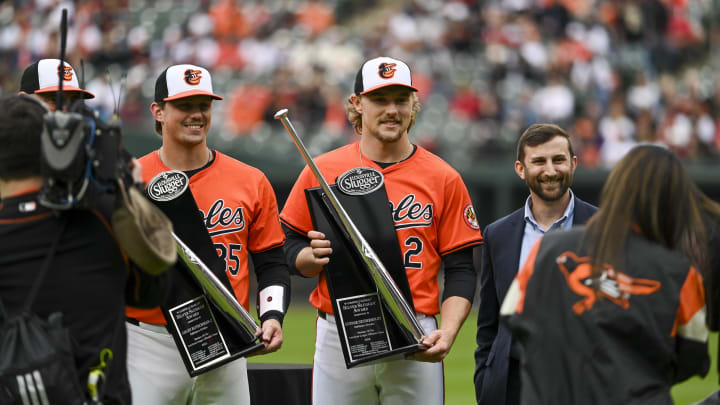

The four main lookalikes are 22-year-old shortstop Gunnar Henderson, 26-year-old catcher Adley Rutschman, 25-year-old outfielder Heston Kjerstad and 20-year-old second baseman Jackson Holliday. Kjerstad and Holliday, both 2023 Futures Game alumni who struggled in their recent call-ups, are currently at Triple A. Henderson and Rutschman are currently the Orioles’ best players.

All four stand a bit over 6 feet tall, all wear their light hair curled around their ears, all boast high cheekbones and the bright eyes of someone who watched the 115-loss 2018 Orioles only from afar. Until Henderson began experimenting with facial hair this year, all were clean-shaven.

Most people around the team insist that the resemblance is superficial. “They’re all young guys,” says 30-year-old lefty Cole Irvin. “They don’t know what they want to do yet for a mustache or a beard.”

Still, Irvin admits that from behind, he has occasionally mixed up Rutschman and Kjerstad. (Manager Brandon Hyde says his bigger problem is that 24-year-old lefty Cade Povich is a dead ringer for Hyde’s 16-year-old son Colton.)

Players and coaches can tell them apart. Fans can’t always. Last year, when the rookies dressed up as Mr. Splash, a be-snorkeled team employee who celebrates Orioles extra-base hits by spraying water at the crowd in the Bird Bath section, a fan got Henderson’s attention. “Adley!” the person screamed. So Henderson dutifully scrawled Adley Rutschman. “It wasn’t even a signature,” he says now, with a grin.

One official, in a nod to the Orioles’ reputation as cutting edge, jokes that the team used artificial intelligence to select players based on the idea that facial symmetry implies good genes, which implies physical health, which implies exit velocity.

Not everyone finds the idea so funny. Vice president of communications Jennifer Grondahl, who overheard one of the interviews for this story, took exception to the premise, insisting that she did not see the resemblance and that the Orioles have many prospects who look different.

This story does provide a window into more than just a shared barber and skincare routine. The young Orioles look similar because they mostly took a similar path to the big leagues, starting with being white kids born in the United States. That population is overrepresented in the Baltimore organization as a consequence of a longstanding policy of late former owner Peter Angelos, who viewed Latin American prospects as a risky investment. Only when his son John Angelos took over the day-to-day operations of the team, around the time GM Mike Elias was hired in November 2018, did the organization begin taking the international market more seriously.

According to Spotrac, the Orioles did not spend more than $800,000 on an international prospect until they gave catcher Samuel Basallo $1.3 million and shortstop Maikol Hernández $1.2 million in 2021. (Ten teams, including the famously thrifty Tampa Bay Rays, were doling out seven-figure deals as early as ’12, which is as far back as Spotrac’s data goes.) That ’21 signing class, to which the Orioles paid roughly $5.75 million, made more than the classes of ’12 through ’18 combined. Today nine of Baltimore’s top 30 prospects, according to MLB.com, hail from abroad, but in ’20, when today’s major leaguers were farmhands, that number was only two.

Most of those Latin American players, in their teens and early 20s, are still working their way through the lower minor leagues. In the meantime, while the team built its international system, it leaned on the draft, where Black players are underrepresented. (Black players are underrepresented everywhere in baseball, where they make up only 6.0% of rosters despite comprising some 14% of the U.S. population.) Because the team was so bad for so long, the Orioles picked at the top of the first round, which is where they found Rutschman (No. 1 in 2019), Kjerstad (No. 2 in ’20) and Holliday (No. 1 in ’22). (Henderson had to wait for the second round in ’19.)

And so in a league in which 27.5% of players were born outside the U.S., the Orioles’ roster is only 19.5% international, and the prospects who have graduated together and who form the Orioles’ young core are fairly homogeneous. The plan is for that to change soon—Basallo in particular looks promising, and he could debut next year.

He will join a team full of diamond doppelgangers who laugh at their facial similarity but take pride in another resemblance, summed up by Elias: “The way they look alike is they’re all damn good ballplayers.”