Happy 50th, 1970 White Sox!

A half-century ago today, the White Sox began a spiral down to the cellar of the AL West, below two second-year expansion teams, with a 12-7 loss to the ("first in war, first in peace, last in the American League") Washington Senators, kicking off a 6-19 run that would end in a doubleheader sweep by expansion Milwaukee July 7, the nightcap lost 1-0 on a throwing error on a sacrifice bunt. The streak was emblematic of the season. By July 19, the team had sunk to season-worst 31-62 (.333), virtually assured of immortality for its ineptitude.

Yep, 50 years since the White Sox set their record for losses, 106 of them. For half a century, 1970 has served as the "at least" season for Sox fans — as in, "at least it's not as bad as 1970," which we've had to fall back on for a long time now.

When there's such a grim occasion in sports, there's a natural fan reaction to believe things weren't as bad as they seemed. But in this case, yeah, they were, if anything, worse than they seemed, absolutely. It's not easy to go from a 17th straight winning season to 56-106 in just three years.

There was a light at the end of the tunnel, though, and it didn't turn out to be an oncoming train. Still, it was one nasty tunnel to get through.

To try to understand the total collapse of both the team and the whole Sox organization, let's go back to look at a bunch of bad things that came together. Forgive the use of virtually every synonym for "awful" in the thesaurus. When it comes to numbers, including player evaluations, I'll stay with those from Baseball -Reference, both for consistency and to try to keep the statistics from being completely overwhelming.

Things outside White Sox control: way, way, out of control

The last years of the '60s weren't just bad years for the White Sox, they were seriously horrible years for Chicago. Racial tensions turned volcanic after the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr., in April 1968, leading a large portion of the white population to strictly avoid the south side, even Mayor Daley's home enclave of Bridgeport.

A few months later, the entire nation was treated to the Kafkaesque horror of what was happening outside the Democratic National Convention. Anyone thinking Chicago would be a nice place to visit on their vacation turned toward somewhere more peaceful, less like a militarized police state — maybe, say, Saigon.

White Sox attendance fell precipitously. It hadn't been less than a million in the 162-game era, until going barely under in 1966 and '67. Then it plunged to 800,000 in 1968 and 538,000 in '69, both of those figures considerably influenced by Chicago playing several home games in Milwaukee, where the Braves were gone with the wind after '67. The 495,000 total in '70, with Milwaukee taken by the flight of the Seattle Pilots, was fewer than 6,000 per game, given the Sox somehow had 84 home games.

To make matters worse, That Other Team in Town, with four future Hall-of-Famers, was actually pretty good in those years, so people seeking a baseball fix had an alternative.

The man at the top: Allyn, Allyn, in free

John Allyn had taken over the main ownership role of the Sox from his brother, Arthur, in 1969. Theoretically, this was to prevent the team from being sold to people who would move it to Milwaukee or Kansas City ... which doesn't explain why the Sox played home games in Milwaukee in '68 and '69, or why the people who actually owned the Sox didn't have control over a sale. Sure seems like the real reason there was no move was that the new Seattle Pilots franchise bolted to cheeseland first.

That bit of possibly twisted history, that Allyn saved the team from a move, doesn't jive with the constant floating of rumors that the Sox were headed to just about any large city between Vancouver and Buenos Aires, a sort of Threat-of-the-Month club. I moved to Chicago after getting out of the Navy in 1971, and the general feeling, right or wrong, was that Allyn had total disdain for Chicago and Chicago fans, a disdain fully reciprocated.

Hence the horrible attendance figures — well, those things and the dreadful team.

The organization: Coming up Short and into the Gutter(idge)

Ed Short had been the general manager since 1961, so there were some good years with him in the front office, even though he was from the paper-pushing side of the company, not the baseball side. After 1967, though, it was another Short story. Well, actually beginning in 1965 — see the draft bit below.

What to say about manager Don Gutteridge? Let's put it this way — being a major league manager is usually a job for life, just one where you have to change outfits every few years. No matter how bad you are, some other team will take a chance on you. Gutteridge never had another managing job. 'Nuff said.

The longtime Sox coach had taken the helm early in the 1969 season, after Al Lopez, who was coaxed out of retirement late in '68, had to retire again with health problems. Gutteridge lasted until Sept. 1, 1970, ending up with a 109-172 record. (Per managerial WAR, Gutteridge cost the White Sox 3.5 wins per season, ranking 26th of 32 all-time South Side skippers.)

Gutteridge's main accomplishment was to be so bad he got fired during the season, giving way briefly to coach Bill Adair, who in turn gave way to Chuck Tanner. Tanner, perhaps the best manager ever to have a losing career record, did even worse with the 1970 team (3-13), but he didn't just see he light at the end of the tunnel, he was the light at the end of the tunnel.

Do you feel a draft in here?

The Sox made their terrific 17-year winning run when they were the second-largest market in the American League, and behaved like they were. Had it not been for the bottomless pockets of the Yankees, the GuRF would be lined with pennants from those days.

Then came the draft — the baseball one — in 1965, which meant it started to have an impact at the big league level a few years later. Suddenly, you had to make smart decisions when it came to the acquisition of young talent. Teams could no longer just outbid other, smaller-market teams, because free agency was just a gleam in Curt Flood's eye.

Smart decisions have seldom been part of the White Sox DNA.

Now, to be fair, the baseball draft is pretty much a crapshoot. Even today, with all the data available, teams make lousy picks, and bypass greatness on good ones. The White Sox were just one of 24 teams who took a pass on Mike Trout in 2009, though going for Jared Mitchell may have been a particularly awful decision, fitting into traditional Sox drafting.

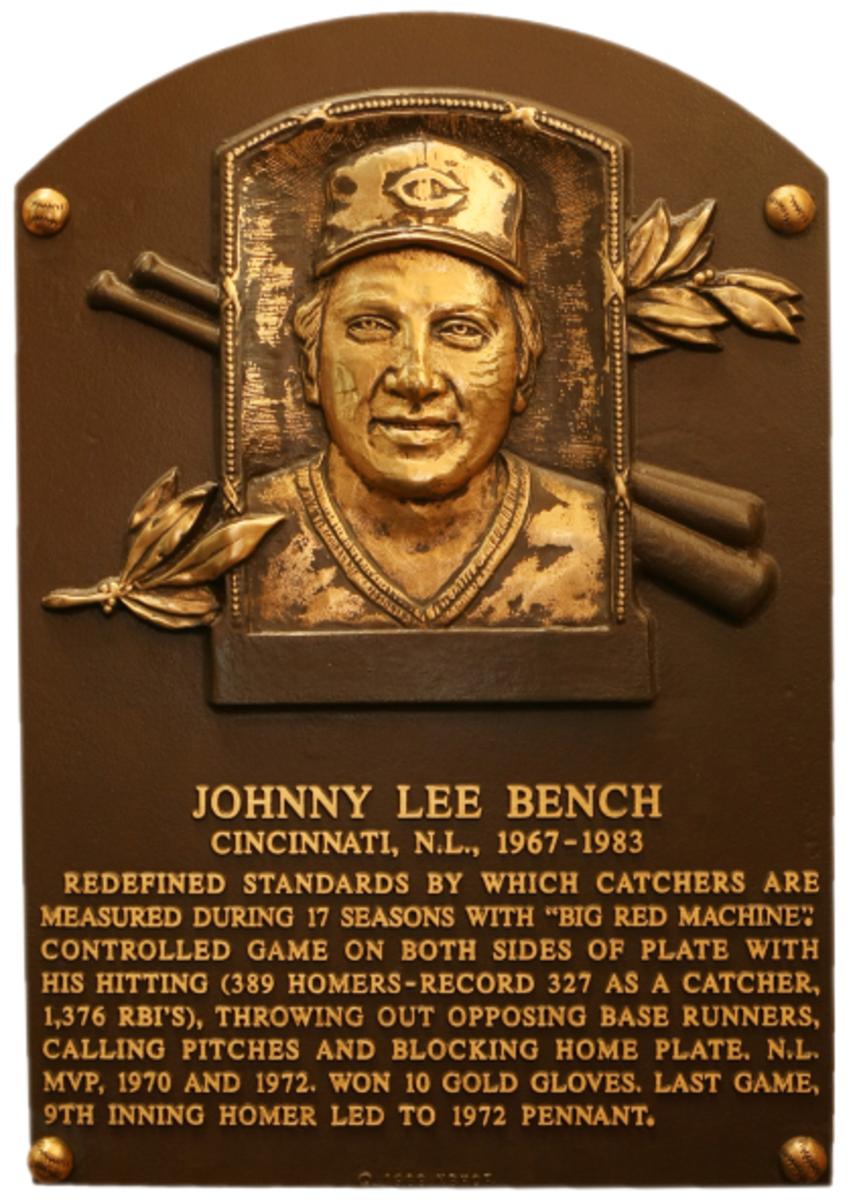

In 1965, it was even more of a matter of luck. Still, the Sox were particularly terrible at it. In the first round they picked Ken Plesha out of Notre Dame. Now, Plesha turned out to be a fine gentleman and a leading citizen of his home town of McCook, to which he got to return quickly, because he never made it past an A-ball shot in 1966. Because the Sox went for a catcher, perhaps it would have been better to choose some other backstops still available, such as, oh, say, a kid named Bench.

Making a mistake with Plesha was a mere trifle compared to the disaster of the rest of the draft. The Sox made 41 picks, of which only five had so much as a sip of coffee in the majors, let alone a cup. The only one who went beyond a sip was pitcher John Montague, who, beginning another Sox tradition, didn't sign with them, but did with the Orioles two years later ... and turned out to be a negative-WAR player, anyway.

The Sox did a shade better in 1966, in the first round picking Carlos May, who had 10.5 WAR career. They made a really nice choice of 20.3 WAR Geoff Zahn in the 34th round, but, of course, he didn't sign. Their best pick in '67 was Jim Norris, in the 31st round, but, again — please join in on the chorus — he didn't sign.

The 1967 draft, you ask? Don't. Of just three picks who made it to the bigs at all, the only one to actually sign with the Sox was pitcher Denny O'Toole, of the no-major-league-wins, 5.04 ERA, 0.2 WAR O'Toole's.

I believe you get the picture.

Enough background, let's head on out to the park — the one with a fake turf infield

The 1970 season was the second of the bizarre combination of an artificial turf infield and real grass outfield, reportedly because the Sox couldn't afford a full turf job. It was the ballfield equivalent of wearing plaid pants and a striped shirt, so it was really appropriate for the 1970 team.

In keeping with a then-recent big movie hit, Comiskey had the good (rookie organist Nancy Faust), the bad (the field and the ugly (the team).

And, since we can't very well avoid it, on to the team

Part 1: the offense

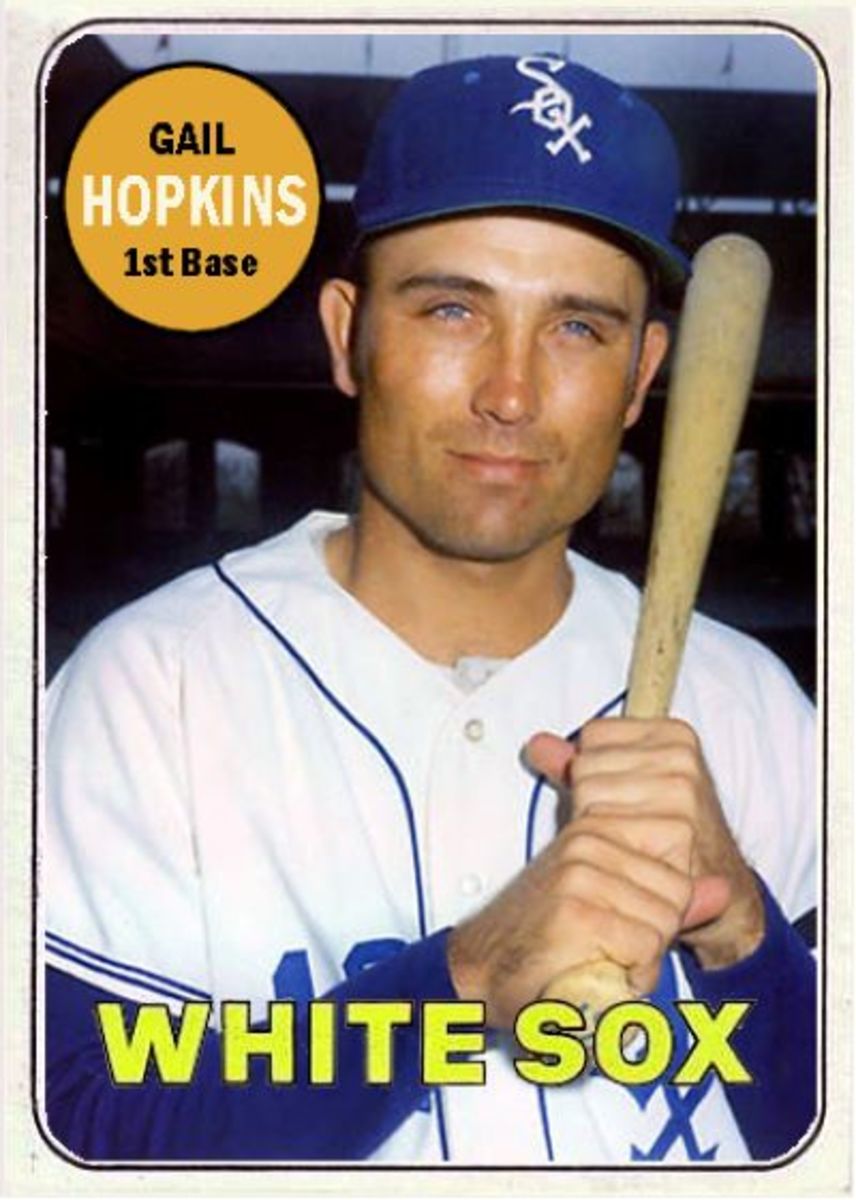

The offense was by no measure the worst aspect of the 1970 White Sox, despite severe weaknesses. In the ultimate evaluation of an offense, they scored 633 runs, good enough for eighth in the 12-team league ... albeit two of those 12 were second-year expansion teams.

MLB had made changes in 1969 to increase offense, particularly in lowering the mound, and it worked. Teams averaged 555 runs in 1968, 703 in 1970. The Sox increased even more, going from 463 to 633. It wasn't enough.

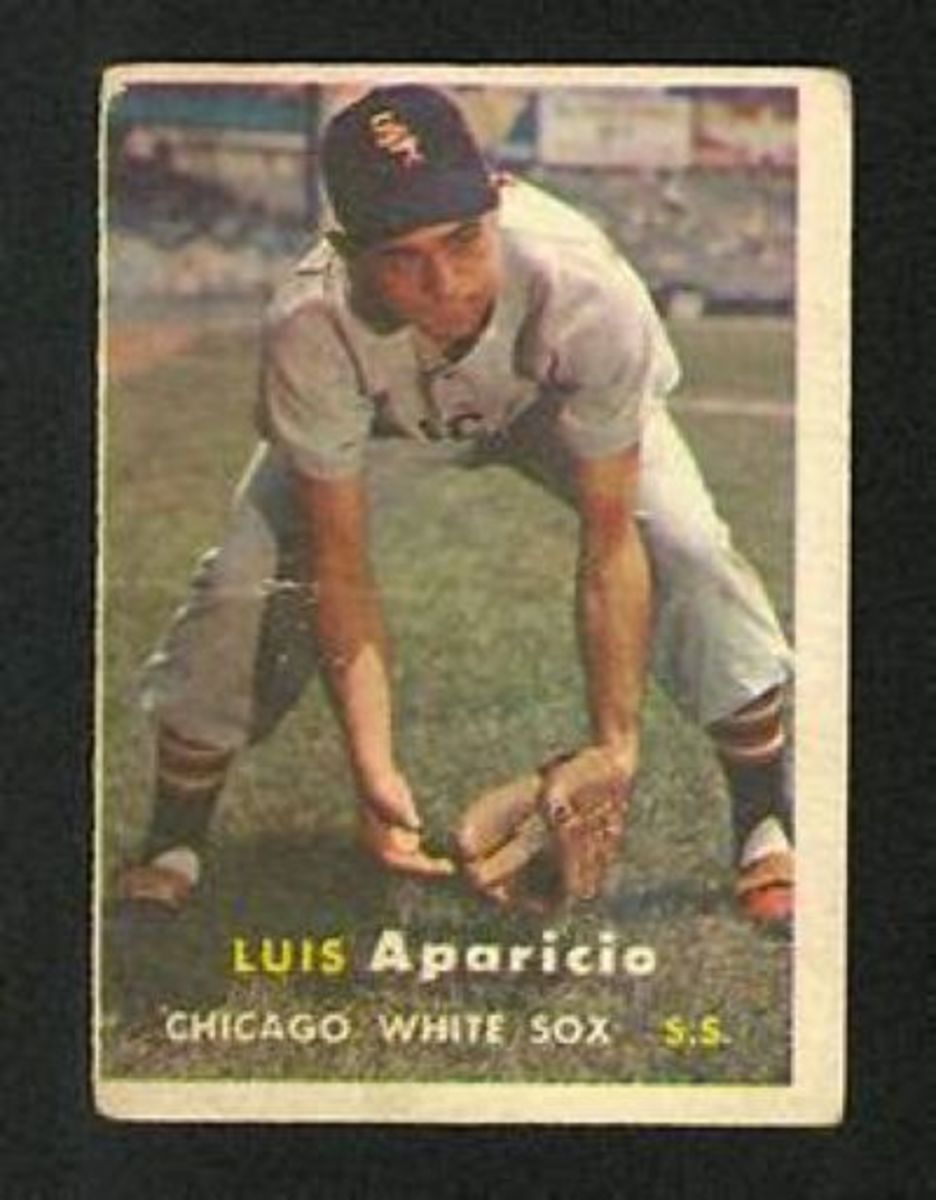

The batting average was fine, a fourth-place .253, but the problem with refusing walks that has plagued recent editions of the White Sox showed up then as well — 11th in free passes, so down to ninth in on-base percentage. Luis Aparicio, at age 37, led the team by far with a .313 average, but most starters were also respectable (Little Looie was among the team leaders in walks as well with 53, despite hardly being an extra-base threat). They weren't as bad as recent squads in striking out, coming in ninth.

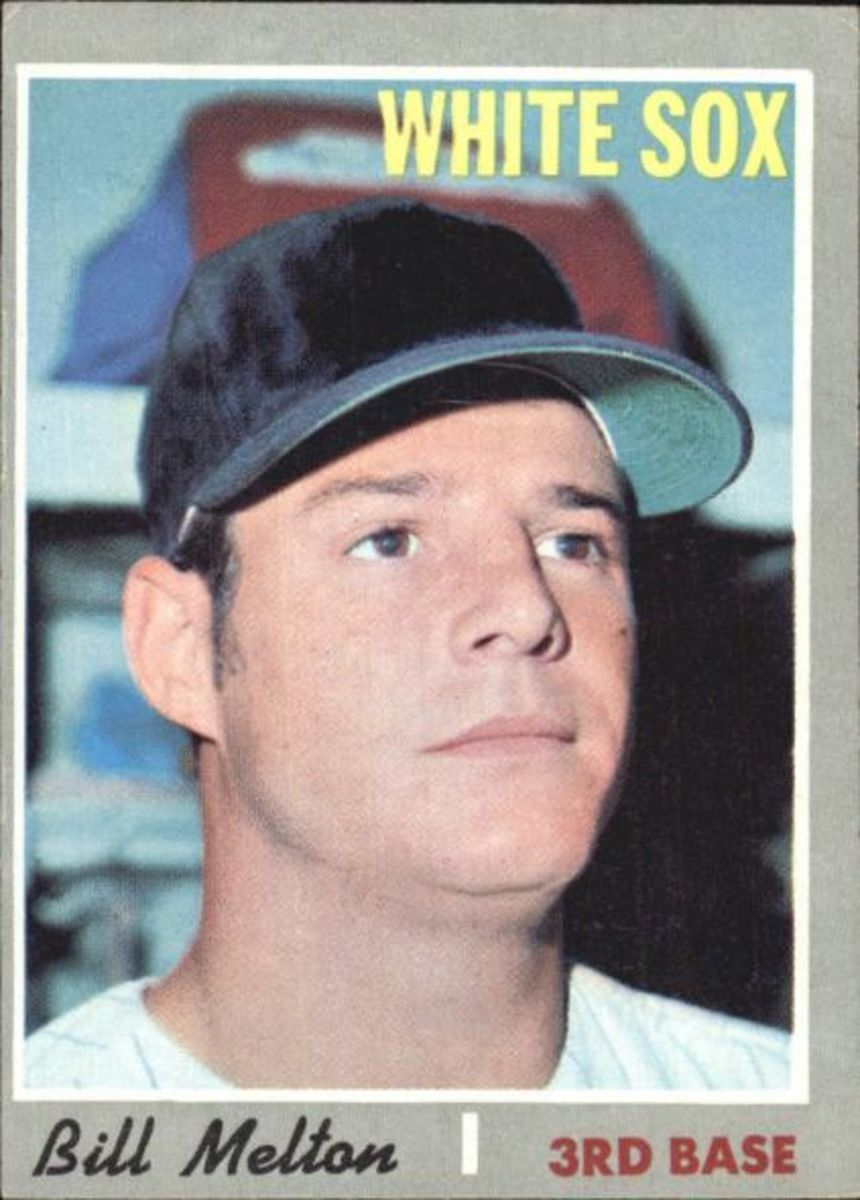

There was a definite lack of power, though — ninth in homers, slugging and total bases. Bill Melton's 33 dingers — the same number with which he'd lead the league the next year — were more than a quarter of the team total, with Ed Herrmann next with 19, and only May among the rest reaching double-figures, with 12.

The 17-year winning streak never depended on power, though — it relied on speed and smarts. Unfortunately, the 1970 team made up for a definite lack of power with an absolute lack of speed. Not only were they ninth in the AL with 29 stolen bases, but they got thrown out more than they succeeded. Aparicio's major league-leading years were behind him, as this first season in single digits, and nobody picked up the slack.

Now, maybe you're thinking, "Perhaps they were merely ahead of Moneyball and did not care for the philosophy of stolen bases." OK, then let's look where they placed in the other major speed-dependent category, triples — hmm, last in the league. Case closed.

So the offense was weak, but not disastrous — what about the D?

Funny you should ask. This is where the real ghastliness begins.

Let's start by saying the White Soxwere first in the league in errors, with 165 — nine more than anyone else. Even the 2019 team didn't come close to that, with 118.

True, there sure seems to have been a major change in official scoring since 1970. Back then, if somebody booted a ball or threw it wildly, it was an error, period. You touched it, you didn't catch it, you were going down with an E. Now, players have to drop the ball multiple times and throw into at least the upper deck — then both the fielder and hitter have to not bother to complain to the scorer. Influence of big money, and all that.

Still, the 1970 Sox were awful defensively, with -67 runs saved, worst in the league by a dozen. Catchers Herrmann and Duane Josephson racked up -16 all by themselves, Melton was at -8, May -7, and so on.

And the awfulness was despite some really good play up the middle. The Sox led the league in assists (by a mile) and double plays, thanks to Aparicio, who won his umpteenth Gold Glove, and second baseman Bobby Knoop, who had a shiny metal mitt collection of his own. Ken Berry in center was no slouch, either. But if you hit anywhere else, just keep on running.

Sure, assists are largely a function of ground balls and a pitching staff that doesn't strike people out (check!), and DPs are partly a function of having guys on first with fewer than two outs a lot (check!), but still, those guys were good. They were just stuck with the rest as teammates.

Part of the problem was that, as now, the Sox were loaded with designated hitters — May and Melton were made for the job — but the DH hadn't been invented yet.

One interesting stat: The Sox were last in MLB in putouts. When I first saw that, I admit to thinking, "Boy. the outfield must have been terrible." Then I realized, no matter how bad or good you are, you get the same number of putouts per inning: 1-2-3, three putouts; four errors and six runs, three putouts. The explanation is that when you're 29-53 on the road, you don't take the field for the bottom half of many ninth innings. Add in only making it to extra innings 10 times (eight losses) and you end up with just 26 ½ putouts per game, one less than the league-leading Orioles.

One other interesting defensive situation that year. Melton was so bad at third that Gutteridge moved him to right field for a try there. It was a reasonable experiment for a week or two, but hard to comprehend lasting 70 games. That was even though Melton was no better in right, and his replacement, Syd O'Brien, could neither field nor hit, coming in third in the league in errors with 25 despite playing only 909 innings while replacing Melton and Knoop.

Melton never played the outfield again.

Gutteridge, at the risk of being repetitive, never managed again.

OK, we've put off the pitching long enough

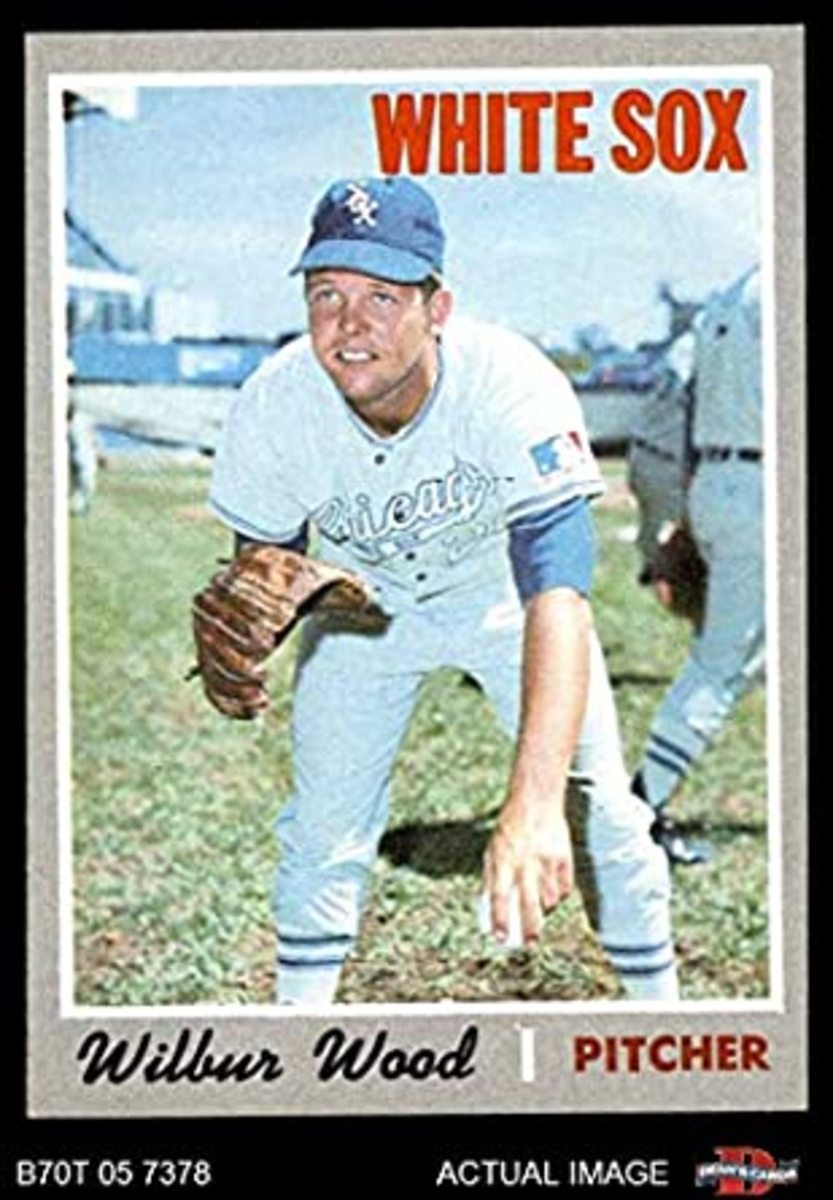

The 1970 White Sox pitching squad was not only 12th out of 12 in ERA by a mile, they were also last in runs, WHIP, homers, and strikeouts (hence all those assists). The bright side was that they were only 11th in wild pitches and hit batters, and what was, for them, a highly successful eighth in walks.

To be fair, the pitchers had a combined 6.8 WAR, which was way, way better than the position players' 4.3. But Tommy John, who went 12-17 with a 3.24 ERA, had 5.5 WAR all by himself, and he and Wilbur Wood combined for 8.0, so you can see where that leaves the rest of the guys. Joel Horlen was next best with a 0.7, with a 6-16 record.

If you prefer ERA+ as your measurement, John at 118 and Wood at 135 were the only pitchers better than 100. Gary Janeski was second among the starters, at 80.

Speaking of Wood, the rotund butterflyer — well, not rotund yet — managed to lose 13 games as the closer, despite how well he pitched (Wood later said he hated coming in to a tie game that year, because he knew they'd find a way to lose). That was the last season as a reliever of Wood's 50-WAR career. Unlike Gutteridge and all his previous managers, Tanner figured out that Wood should be starting, not relieving, leading to four straight 20+ win seasons, with more than 300 innings eaten each time, which probably explains the weight gain.

Having embarrassed the pitchers with that WAR stuff, time to humiliate the hitters

As mentioned, the pitchers had a combined 6.8 WAR, but the position players an even lower 4.3. Basic WAR guidelines say you should be at least at 2.0 to be a major league starter, so the hitters fell a trifle short.

That 4.3 is actually worse than it looks, because Aparicio — remember, he was 37 — had 4.8 WAR all by himself. Yep, the rest of the team combined was worse than a Triple-A squad.

Melton actually did fine, his 2.6 being impacted by a -1 on the defensive side. The only other player to hit the 2.0 level was Herrmann, with May close at 1.9, both dragged down by lousy D.

The rest? Better not to look.

So put it all together, and what have you got?

Well, you've got a 56-106 record, 25-53 on the road, 31-53 at home. You've fewer than half a million in attendance. You've got a last-place team that even convenience-stored the two second-year expansion outfits, going 7-11 against both Kansas City and Milwaukee.

With 633 runs scored and 822 given up, you've got a team Pythagorean record that should have been 62-100, that cumulative WAR suggests should have been 59-103 — both pathetic, but better than the final tally.

And, of course, you've got by far the worst team in the major leagues, 42 games behind Minnesota in the AL West.

Didn't you say something about a light at the end of a tunnel?

Yep, and there was a bright one.

With Tanner managing and Stuart Holcomb as GM, the Sox came to life beginning in 1971. They jumped from 56 wins to a very respectable 79 — a 23-win leap only topped in Sox history by the Black Sox, but the 1919 team had the advantage of playing more games than in war-impacted 1918.

The improvement came even without Aparicio, who was traded to the Red Sox for Luis Alvarado, who couldn't hit, and Mike Andrews (yes, the Mike Andrews Charlie Finley made famous), who couldn't field.

The 1971 Sox managed to score even fewer runs, with 617, but the pitching came through big time, giving up just 597.

Melton hit 33 dingers again, this time to lead the league. A whole new outfield, with May moved to first, helped the position players to 12.6 WAR, though Melton at 5.7 was the only player to reach major league starter level.

As for the pitching, the big star had been there all along, just wasted as a reliever: Wood won 22 games and sported an 8.7 WAR. Tom Bradley, picked up in a trade with the Angels, won 15, John was solid as usual, and Bart Johnson proved a very able closer. All told, 27.1 WAR.

And as for the defense, well, Melton had the highest dWAR, which should be all you need to know.

Yeah, yeah, by Pythagorean and WAR they should have won more. For that, just wait until '72. Besides, with 23 more wins despite having largely the same crew, minus your best player (Aparicio), who's complaining?

Attendance almost doubled, Harry Caray came to the broadcast booth, and trading for Dick Allen was just one year away.

Must have had a great draft, picking No. 1, right?

Well, uh, it was more a different kind of No. 1. They p%($!ed away one pick after another.

First pick of the whole draft was Danny Goodwin, who of course — sing it, now — did not sign. And he wasn't much when the Angels made him the No. 1 overall pick four years later, either. Other first-rounders in that draft included Jim Rice, Frank Tanana and Rick Rhoden.

The Sox did better in round two, with serviceable outfielder Bill Sharp, a 10 WAR career player. Amazingly, he did sign. Less amazingly, the Sox left second-rounders Mike Schmidt and George Brett for others.

Hey, we got 23 more wins. What more did you want?

Besides, too much light at the end of the tunnel is bad for your eyes.