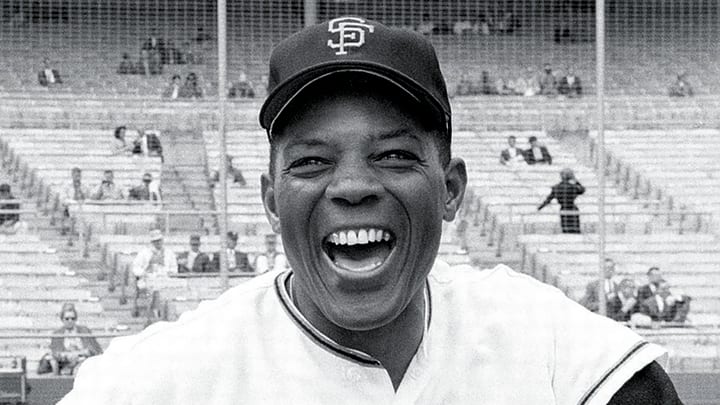

Willie Mays Brought Unrivaled Style to America’s Stuffy Pastime

Tom Verducci, Tom Verducci

Willie Mays, who had just turned 20 years old two weeks earlier, was sitting in a movie theater in Sioux City, Iowa, with his Minneapolis Millers teammate, Ray Dandridge, who was still toiling in the minors at 37. The movie was Lightning Strikes Twice, a drama about a New York actress who falls for a dude ranch owner recently acquitted of murdering his wife. It was May 24, 1951.

Suddenly, an announcement pierced the darkened theater.

“Willie Mays, please report to the office.”

At the theatre office Mays found his Minneapolis manager, Tommy Heath, waiting for him.

“Come with me right away,” Heath told the kid. “You’re going to the Giants as soon as we can get you on a plane.”

The New York Giants were playing in Philadelphia the next day against the Phillies. But the team first brought him to New York, where Willie, after getting in at 4 a.m., posed for publicity pictures with Giants manager Leo Durocher and owner Horace Stoneham.

It seemed a big ask to show off the phenom in front of the New York press before Durocher would have him batting third that night in Philadelphia. But the kid from Fairfield, Ala., just outside of Birmingham, stepped into the spotlight as if he owned it from that very first day.

“No, I’m not scared a bit,” Mays said. “I think I’m gonna like it fine. My father was a baseball player and I’ve been playing baseball since I can remember.”

Mays was born not just to this game, but also to the essence of why we watch it: it entertains us.

From his first graceful strides in 1948 across Rickwood Field in Birmingham, Ala., as a 17-year-old playing only home games for the Birmingham Black Barons—his father, Cat, wanted his son not to miss any high school classes—through his years of unique greatness with the Giants and his full-circle goodbye season with the New York Mets, Willie Mays was a genus of one. He was a bolt of lightning, a game-changing force of athleticism and beauty on the diamond that snapped you to attention. There is no second strike of his kind of lightning. The likes of Willie Mays were seen never before and will never be seen again.

Mays passed away at age 93 Tuesday, just two days before he and his fellow Negro Leaguers are to be honored at a game between the San Francisco Giants and St. Louis Cardinals at Rickwood Field. Opened Aug. 18, 1910, Rickwood is the oldest ballpark in America. It is the Mother Church of baseball. It is the cradle of the career of the greatest all-around player who ever lived. And now it is where we say goodbye.

The way Willie spoke of his ease on the brink of his New York debut —“I’ve been playing baseball since I can remember,” like it was the act of breathing—captures the essence of Mays. He was born to baseball. No one could hit, hit with power, field, throw and run as well and as thrillingly as Mays.

Today when you picture Willie in your mind’s eye, you see movement. He is the summer wind. Running out from under a cap, which he intentionally chose a size too small just for that visual effect. Stealing bases. Running down fly balls. The flick of his glove for a basket catch. His windmill of a swing. The most famous catch in baseball history.

“I was always aware that you play baseball for people who paid money to come see you play,” Mays said in 24, a book he co-authored with John Shea. “You play for those people. You want to make them smile, have a good time. I could make a hard play look easy and an easy play look hard. Sometimes I’d hesitate, count to three, then I’d get there just in time to make the play. You’d hear the crowd. Sometimes you had to do that in order for people to come back the next day.”

The catechism of baseball is found in numbers. The statistics define greatness. Numbers, numbers, numbers. We memorize them like hymns. But no player is better defined by how he did it than what he did than Willie Mays. You would no more define Mays by his 3,293 hits than you would Miles Davis by albums sold.

George Gershwin once said “Life is a lot like jazz. It’s best when you improvise.” So is baseball. And Mays is to baseball what jazz is to music. He perfected flourish.

He adopted the basket catch, for instance, while playing ball in the Army just because it was fun. A 24-time All-Star, he hit .307 in those showcase games.

His elan dates to the Black Barons of the Negro Leagues, where the style of play was built on drawing crowds to forget the hardships of life. His mentor was Piper Davis, the team’s player-manager who encouraged his derring-do style.

With the Giants in 1955 he became the only player—and still is—to hit 50 home runs and lead the league in triples.

His speed awakened what had been a boring, station-to-station game. The four lowest stolen base rates of all time occurred between 1950 and 1955. Then in 1956 Mays became the first player in 12 years to steal 40 bases. It was the first of his four straight stolen base titles. Teams searched for the next Willie Mays, opening the game to more diversity of style … and skin color.

His most spectacular skill may have been his defense. As teammate Monte Irvin once said, “It was his solemn duty to catch a ball that wasn’t in the stands.”

Day after day, year after year, Mays, only 5-foot-10 and 170 pounds but blessed with strong hands and wrists, made sure he was out there putting on a show for the fans. He is the most powerful hitter ever for his size. Only two men no taller than 5’10” have hit more than 360 home runs: Mel Ott, who hit 511, and Mays, far out front with 660.

But those are numbers. The essence of Willie could be found on St. Nicholas Place in Harlem in the early 1950s. Mays lived there in a ground floor apartment. Many a morning, the neighborhood kids would knock on his apartment window, wanting the best baseball player in the world to come out and play stickball with them. He did. Then he would buy them ice cream. Then he would walk the few blocks to the Polo Grounds and play baseball like nobody had ever seen before.

Mays played with such artistry that those lucky enough to witness it would tell their children, “I saw Willie Mays play,” as if they had seen Hemingway in Madrid or Maria Callas at the Met.

The actress Tallulah Bankhead once said there have been only two geniuses in the world: Willie Mays and William Shakespeare. Mays was a baseball genius. He positioned the Giants’ defense and game-planned for and against pitchers. But the true genius of Willie Mays is captured in his nickname: The Say Hey Kid. Cat Mays’s son honored the purist version of baseball that we hold so dear: that this is a kid’s game. It is designed to be fun.

On Thursday, in the Mother Church of Baseball, we will say goodbye on the same sacred ground where baseball said hello to Willie. Playing with and against grown men in a segregated South—the Black Barons were barred from using Rickwood’s locker facilities, so they dressed at black-owned motels downtown—Willie said he learned hard and he learned fast in the Negro Leagues.

“My teammates from the Birmingham Barons were really the ones who made me understand about life,” he said. “We played at a time when baseball was becoming open to everybody; so we were playing for generations of players who were held back. We had a lot to play for, not just us.”

Willie turned 93 on May 6 at his home in the Bay Area. One of the many people who called him that day was Joe Torre, a longtime friend. Mays’s health had been declining for years. He was not expected to attend the game at Rickwood. Torre called expecting only to talk to the caretaker for Mays, telling her to wish Willie a happy birthday and that he was thinking about him. Upon asking who was calling, Mays insisted on getting on the phone.

“When are you coming out here?” Mays said with a laugh. “I’ll take that as an invitation,” Torre said.

They spoke for 10 or 15 minutes. “He was the same old Willie,” Torre says.

By that, he meant the Say Hey Kid, the same Willie with that infectious high-pitched laugh and that unmistakable boyish joy. Willie made the world a sweeter place.