The Blazing Contradiction of Justin Gaethje

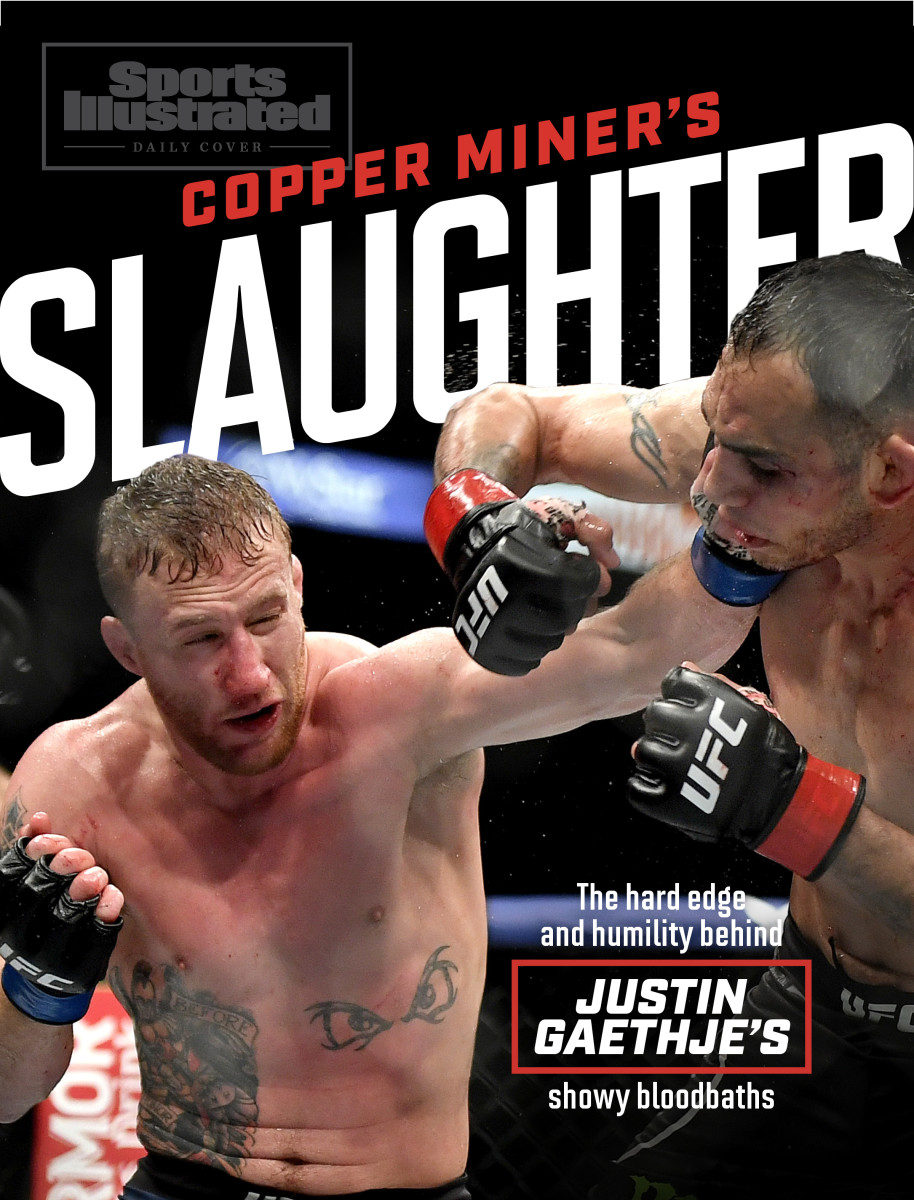

There will be blood. Lots of it. There will be bloody noses and lips and knuckles. Blood will trickle from cuts. It will streak and spackle the canvas, leaving it looking like a slaughterhouse floor. When Justin Gaethje fights, plasma flows, just as surely as the sun sets in the west.

There will not be blood. No bad blood anyway, Justin Gaethje may want to divorce his opponent from limbs and consciousness. But it is never done with personal animus. It’s not merely about respect or the sharing of some sense of dark comradeship; he often likes the other guy. Here’s a fighter who speaks of opponents—past and future—almost as if describing a teammate. One is “so good that it’s not even funny.” Another “is like a superhero … the best in the world.”

It’s not just other fighters. He “loves” the people that work for the UFC. If you haven’t gotten a selfie with the guy, it’s because you haven’t asked. He begins an interview for this story by volunteering, “Just so you know, I have all the time you need.”

Justin Gaethje is both the UFC’s interim lightweight champion and the sport’s blazing contradiction. He is an enigma wrapped in a riddle wrapped in a rubber suit, as he cuts water before each bout to get down to his fighting weight of 155 pounds. Here is a man who fights with flair and with flare, going about his duties with a fearlessness that borders on recklessness. Gaethje is equal parts fighter and showman, happy to eat 10 punches if it means unloading 11 of his own.

And then, the instant the final airhorn sounds—or more likely, the fight is called off in his favor—he morphs into the modest, pragmatic, golf-playing, sushi-loving guy at the end of the cul-de-sac you’d want to invite over for a barbecue. Gaethje’s fighting nickname is “The Highlight.” His non-fighting nickname might as well be “Justin, the AccuWeather forecast guy.”

The Full Gaethje was on vivid display when he stepped in to fight the favorite, Tony Ferguson, at UFC 249 on May 9. This was a fan-free card held in Jacksonville, during this COVID-19 era when the UFC has picked up market share. In the empty VyStar Veterans Memorial Arena that night, the air was filled mostly by the thwunnnnk of Gaethje’s fists and elbows and feet colliding with his opponent. Gaethje turned Ferguson’s face into a version of carpaccio before the beatdown, mercifully, stopped in the fifth round. Immediately after the fight, Gaethje hugged his opponent. “I love you bro,” he told Ferguson. Who then headed straight to the local hospital.

As the reward for winning that fight, Gaethje gets a date with Russia’s Khabib Nurmagomedov, by most reckonings, MMA’s best pound-for-pound fighter, a man who, by some assessments, is not only undefeated but has never lost a round in the UFC. Which is fine with Gaethje. “What could be a better challenge than that?” he asks. “If you’re looking for a challenge and an adrenaline rush—and I always am—well, that’s a pretty good one.”

The fight was imperiled when Nurmagomedov’s father, Abdulmanap, was struck with COVID-19. Gaethje was quick to take to Twitter, tenderly addressing the man he was slated to face in the UFC’s most anticipated fight of the year. “Sending every positive vibe to Khabib and his Father. The man is a legend. I will keep praying for a speedy recovery.”

When Abdulmanap passed away a few days later, Gaethje was there again. “So heartbreaking to hear this news of the Legend Abdulmanap Nurmagomedov. I’m very sorry @TeamKhabib Your dad passed with a heart full of pride knowing you will carry on his legacy.”

Now, they have agreed to fight at UFC 254 on Saturday, on the UFC’s Fight Island in Abu Dhabi.

Gaethje often gets asked to reconcile his alpha in the octagon, with his omega outside of it. He offered one explanation immediately after he demolished Ferguson, in what surely ranks as the least badass victory speech in UFC history. “It’s not about winning or losing for me,” he explained, while absently removing his bloody glove, to a bemused Joe Rogan. “It’s about not disappointing myself, my family and representing God to the best I can and being a good person and helping my neighbor. … I’m a killer in here. But as soon as I step out of the octagon, you won’t see that in me.”

Another, simpler explanation to try explain the contradiction of Gaethje: Geography is destiny.

***

The folds of eastern Arizona tend to resemble the landscape of Mars, a vast space devoid of much life or vegetation. But 216 miles southeast of Phoenix, you’ll find the Morenci mine, the largest copper reserve in the U.S. In a good year, close to a billion pounds of copper will be extracted from the maw of Morenci.

The mine dates back to the 1870s, when gold prospectors realized that there might be even more valuable lodes in the desert. By 1881, the Phelps Dodge company began stripping the mine. When Arizona entered the Union 20 years later, it was largely on account of Morenci that it took on the nickname, “The Copper State.”

For all its bounty—in fact, often because of it—the Morenci mine has seen its share of fighting. The great Arizona copper strike spanned 1983–86, and at one point grew so tense that the governor summoned nearly 1,000 national guard troops, state troopers, and SWAT sharpshooters. Striking workers were replaced and the union was decertified, marking a major plot point in American labor relations. But Morenci survived the round, so to speak, and it remains an active, profitable mine, and a source of jobs for thousands.

Like his father, Ray Gaethje worked in Morenci for decades, clocking 12-hour shifts for 15 days a month; and then getting the other 15 days off. It was a sort of brutal physical labor that could make you feel like, well, you’d spent the day cagefighting. But it paid the bills, and then some. It enabled Ray to meet his wife, Carolina Espinosa, whose father also worked the mines. And in the company town of Safford, Ariz., the Gaethjes lived comfortably and stably.

“People from the city can’t fathom how different it is, living out there in the middle of nowhere,” says Justin Gaethje. “But I love it and every time I talk about it I always have to be careful, because it sounds like I'm putting it down and I don't wanna do that. It’s just a stable life. [The mining company] owns every building, every school, the grocery store, all the houses. These guys, when they’re on the shift, they’re working their asses off. When they’re off, they’re enjoying their family and being a family man. I commend them for it.”

Ray and Carolina Gaethje (gay-CHEE) raised four kids, two daughters and two sons, twins Justin and Marcus born Nov. 14, 1988. It was such a charmed childhood that, when asked to think about any regret, Gaethje pauses before unloading a story. His father’s lineage and unusual last name may be German. (“Especially in what I do, especially without having a [wild] personality, I think my surname almost serves me well there!”) But, nodding to his mom’s side of the family, Gaethje also identifies as Mexican. Living in Mexico most of her life, his maternal grandmother never learned English; and Gaethje never learned Spanish. “There’s no reason I shouldn’t be able to talk to my own grandmother,” he says. “If we were going to the store, they wanted to use us to teach her English, more so than have her teach us Spanish. I can’t believe I didn’t learn.”

It might have been because he was too busy competing. The family tells the story of Justin once getting bitten by a dog, only to chase the dog and bite it back. He was two years old at the time. And, almost from birth, Marcus and Justin possessed competitive fires they aimed at each other. Every fishing trip, visit to a mini golf course, or car ride became doubled as some sort of brother-on-brother competition.

For all the testosterone sloshing through the house, Justin transferred most of it to wrestling, a sport he had taken up at age four. At Safford High School, he turned in a record of 191–9 and was twice an Arizona state champion. Overcoming an urge to stay local, he went on to wrestle at the University of Northern Colorado.

After his freshman year, he figured he could make some good money coming home and working in the mine. He put in 12-hour days that summer, working a variety of jobs. He once turned in a 96-hour week. He took one sick day, which he devoted simply to catching up on sleep. When he returned to school, suddenly the rigors of college wrestling didn’t seem quite so demanding. By his sophomore year, he’d qualified for the NCAA championships at 157 pounds and was on his way to becoming an All-American.

Late in Gaethje’s college career, UFC royalty paid a visit to the gym. Georges St-Pierre and Donald Cerrone were in Colorado working with Trevor Wittman, an esteemed mixed martial arts coach, and popped up from Denver to spend a day training in Greeley. Gaethje began speaking to the fighters and was entranced hearing about mixed martial arts. He had never so much as been in a street fight. But the ability to marry his wrestling base with a set of skills was irresistible. This was the adult version of chasing the dog that had bitten him. “I’m strong. I’m competitive. I’m good at creating chaos. Yeah, I can do this.”

Still a college wrestler, Gaethje entered his first fight, an amateur bout held at an outdoor venue in Denver. He won in 27 seconds. After graduating with a social work degree, Gaethje spent a few years fighting every three months or so, mostly in Colorado and Arizona. He set up a base in Denver, where he could train with Wittman. It could be described as a monastic existence, if monks were violent. Training, eating, sleeping. Which suited Gaethje fine. “Young guy. No family. Working to get better at something you love? That’s fun!” he says.

It wasn’t just that Gaethje kept winning; it was how. In mixed martial arts, wrestlers have a reputation for methodical, ground-based fighting, long on effectiveness, short on flash. In the vernacular it’s dismissed as “sprawl-and-stall,” or “ground-and-pound.” Gaethje was a one-man rebuttal to this stereotype.

Of his first 10 fights, only one went to distance. Gaethje intuited an unspoken message that a fighter is there, yes, to compete; but also to entertain. His high-risk, high-reward style yielded spectacular finishes and wild swoops of momentum, all the while keeping the cage-side medical personnel alert. Often he would punctuate his wins by doing a backflip off the top of the octagon.

After he dominated the World Series of Fighting promotion, Gaethje’s first official UFC fight came in the summer of 2017. He won Fight of the Night, the bonus the UFC pays to fighters for crowd-pleasing brutality.

Gaethje’s next two UFC fights also won him Fight-of-the-Night bonuses. But there was one problem: He lost them both. The fights were plenty entertaining. And Gaethje inflicted plenty of damage. (“He has reckless abandonment for his own health, for his own limbs, for his body positioning,” said Dustin Poirier, who beat Gaethje in April 2018. “He just acts like he's kicking a soccer ball.”) But Gaethje was suddenly 18-2, not 20-0.

He claimed: “I was having too much fun.” Wittman, his coach, had a different assessment. Gaethje was a “yes-man” to his competitive instincts, more loyal to putting on a show and attempting spectacular moves than to adhering to some semblance of a plan. “It was pretty simple,” says Gaethje. “I had a decision to make.”

***

Gaethje sees himself less as a contradiction than as a melding of nature and nurture. He says he gets his measured disposition from his German side. And his pugnacious streak from his mother’s Mexican side.

Then, there are the echoes of growing up at Morenci. Ray Gaethje worked his ass off and then, once he punched out, was a subdued family man. So, too, does his son shift seamlessly from work to play. And working in the mines—this massive natural treasure; a place where no laborer is indispensable—is a hell of a place to develop some humility. “That’s not the place or the environment to get cocky.”

So it is that Gaethje is well aware of his good fortune. On this day in late June, Gaethje had shot a round of 82 at his favorite golf course outside Denver, and was about to indulge his great indulgences: steak and sushi. “If I go broke, it won’t be because of drugs,” he says, ”it will be because of food. And my mom can’t be that mad for that.”

Justin sees Marcus, home in eastern Arizona, selling equipment to the mine, married and settled down with three baby girls—”he’s in deep,” cackles Justin—and it furthers his appreciation of his life as a pro athlete. “I’m trying to soak it in,” he says. “When I’m 50, I know I'll miss it tremendously.”

At some point in a wide-ranging conversation, talk turns to the 30 for 30 ESPN/UFC documentary on Tito Ortiz and Chuck Lidell, and their struggles after hitting their fighting primes. Gaethje hasn’t gotten around to seeing it. “I could probably tell you exactly what it’s about, because I know what they’re living, what they’re thinking right now,” he says. “One thing about the line of work we’re in, the people who take it for granted are the ones who miss it the most.”

After his two straight defeats, Gaethje didn’t exactly turn into a conservative fighter. But he has tamped down what Poirier calls “the reckless abandonment.”

The clinical and dominant performance over Ferguson was especially gratifying. “I was so proud,” Gaethje says. “I was able to understand that I was influenced by the crowd. I never believed I was, or would be. And then once I got the experience [to fight in a vacant arena], I understand that they do affect me, and I perhaps would have engaged more. Or perhaps taken one or two more chances. And so now my ability to control that is better. Hopefully.”

He’ll get to find out soon. Gaethje has expressed interest in a big-money fight against Conor McGregor, whose manufactured brashness and substance-TKOing style is everything Gaethje is not. (“He’s losing his clout,” Gaethje tweeted of McGregor in a rare blast of trash talk.) Instead, after being handed the interim lightweight belt, Gaethje handed it back, announcing that he wanted the genuine article, which would mean defeating Nurmagomedov.

In preparation for UFC 254 on Oct. 24, he’s been training and running at Red Rocks and trying to eat right, though he permits himself an indulgent meal each week. Asked what it would mean to beat Nurmagomedov, the most electrifying fighter in an entire sport, Gaethje doesn’t want to let himself go there, much less predict victory. He might fight with wild abandon, but get a load of this response:

“The thing with fighting is, it goes away so fast, you’re only remembered by your last fight. You could get knocked out cold and look like an ass. So for me, it’s just staying present and staying humble, because when I do get knocked out, the climb is too steep. And another thing is the higher you go, the lower you come. A lot of times famous people really find themselves in low, low places because they allowed themselves to get so high. And there’s an opposite effect to everything. And if you allow yourself to go there, you will fall, and when you hit bottom, you know it’s so far down because you allowed that.

“So I’m just trying to not let that happen. And, at the same time, enjoy the ride. Does that make sense?”