Why Jim Brown Matters

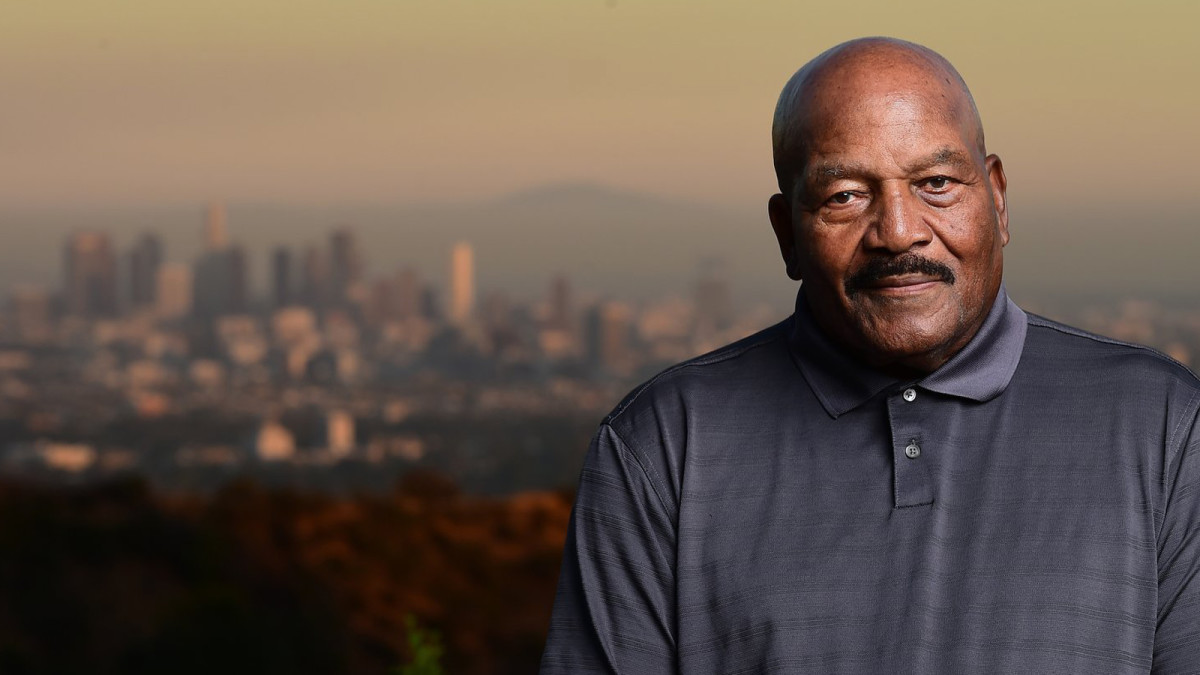

Portrait photographs by Robert Beck for The MMQB

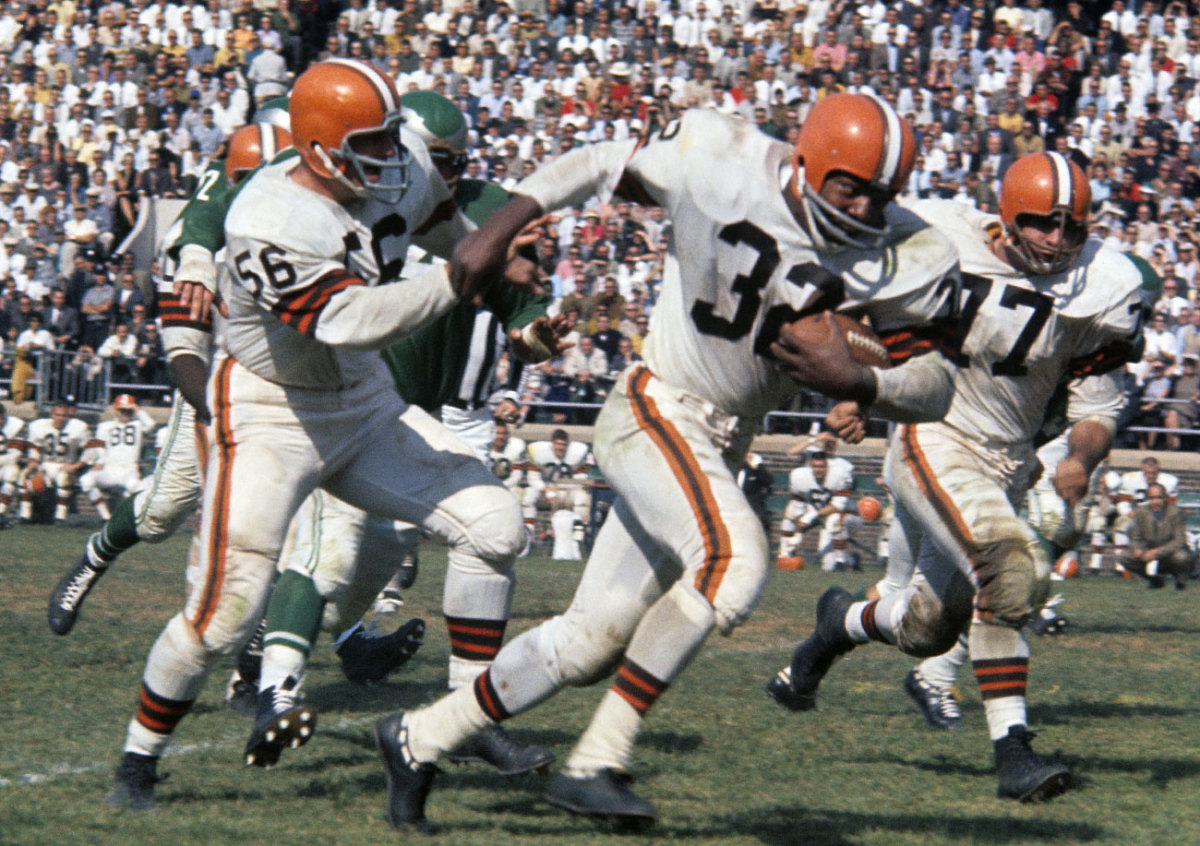

LOS ANGELES — The end came suddenly, and from an ocean away. Fifty years ago, in the 1965 season, Cleveland Browns running back Jim Brown led the NFL in rushing with 1,544 yards in a 14-game season, an astonishing 677 yards more than runner-up Gale Sayers, the phenomenal Chicago Bears rookie. Brown had been voted the Associated Press most valuable player for the third time in his nine-year career and had helped lead the defending-champion Browns back to the NFL title game, a 23-12 loss to Vince Lombardi’s Packers in mud and sub-freezing temperatures at Green Bay’s Lambeau Field. There were other stars in the pre-merger, pre-Super Bowl, 14-team NFL, a professional league that was still in the nascent stages of its climb to multibillion-dollar conglomerate: Colts quarterback John Unitas, Packers running backs Paul Hornung and Jim Taylor and defenders Willie Davis and Herb Adderly, Rams linemen Deacon Jones and Merlin Olsen, Lions pass-rusher Alex Karras and Bears rookies Sayers and Dick Butkus. But Brown towered over the league, a physical and intellectual force like none other in American sports history, at the peak of his powers.

In late November of that year, Time magazine had featured “Jimmy” Brown on its cover. The accompanying story was burdened by the awkward, race-tinged prose of the time, including the headline—“Pro Football: Look at Me, Man!”—and a description of Brown as “…. a fire-breathing, chocolate-colored monster...” Beneath all that, however, the story pushed forward an earnest agenda: to establish that Brown was the best football player in the world and quite possibly the best in history. “There is only one player in the game today whose ability on field commands almost universal admiration, and that is Jimmy Brown.” In the previous three seasons Brown had rushed for 4,853 yards, averaging 5.64 yards per carry and 115 yards per game. He was 29 years old, punished by a violent game but scarcely diminished. In fact, he was better than ever. He was also finished.

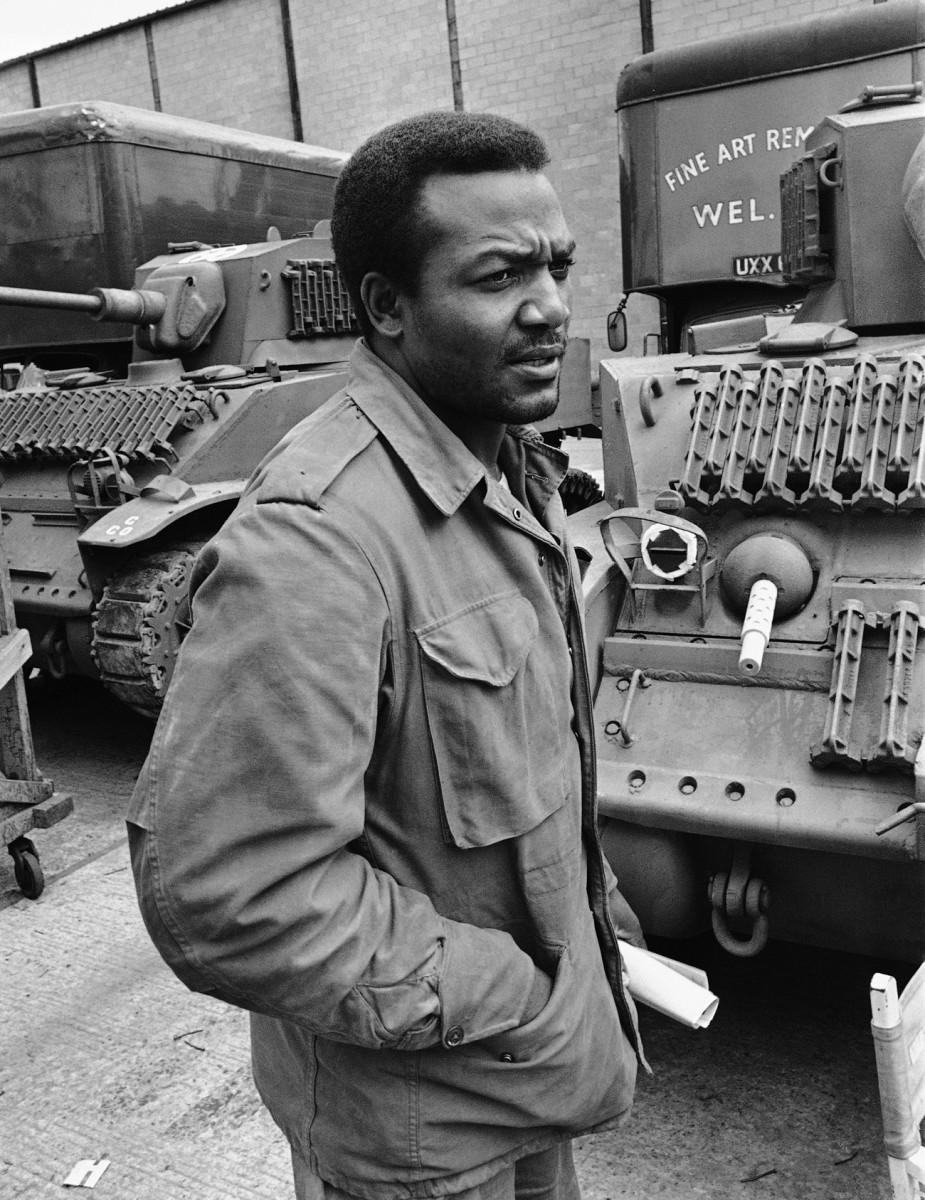

The Browns convened training camp the following July at Hiram College, outside Cleveland, as they had every summer since 1954. They remained a viable threat to Lombardi’s budding dynasty, along with the Colts and the Cowboys, a six-year-old expansion franchise with an innovative young coach named Tom Landry. But they were preparing without their star. Brown was in London filming The Dirty Dozen, a big-budget (for its time) movie that had been beset by production delays. This was Brown’s second film role; he had acted in Rio Conchos during the 1964 offseason and received mostly positive reviews when the movie hit theaters in the fall of that year. Brown was also embroiled in a public dispute with team owner Art Modell, who was fining Brown $100 for every day that he did not report to camp.

In retrospect, what happened next could have been foreseen. Yet it was shocking nonetheless. On the night of July 13, eighth-year guard John Wooten, received a phone call in his Hiram dorm from Brown. They were close friends. Wooten heard a strong yet weary voice on the other end of the line. “He wanted to tell me what was going on,” says Wooten. “He told me to let the guys in the locker room know that he was going to announce his retirement. He felt he had given his all. He didn’t want to go through all this stuff.” Brown also made his decision known to coach Blanton Collier and Cleveland Plain Dealer columnist Hal Lebovitz, who broke the story in his paper.

On the morning of July 14, 1966, Brown conducted a press conference on the set of The Dirty Dozen, wearing military fatigues while sitting in a tall director’s chair placed in front of a tank. “My original intention was to try to participate in the 1966 National Football League season,” Brown said, reading from a piece of paper. “But due to circumstances, this is impossible.”

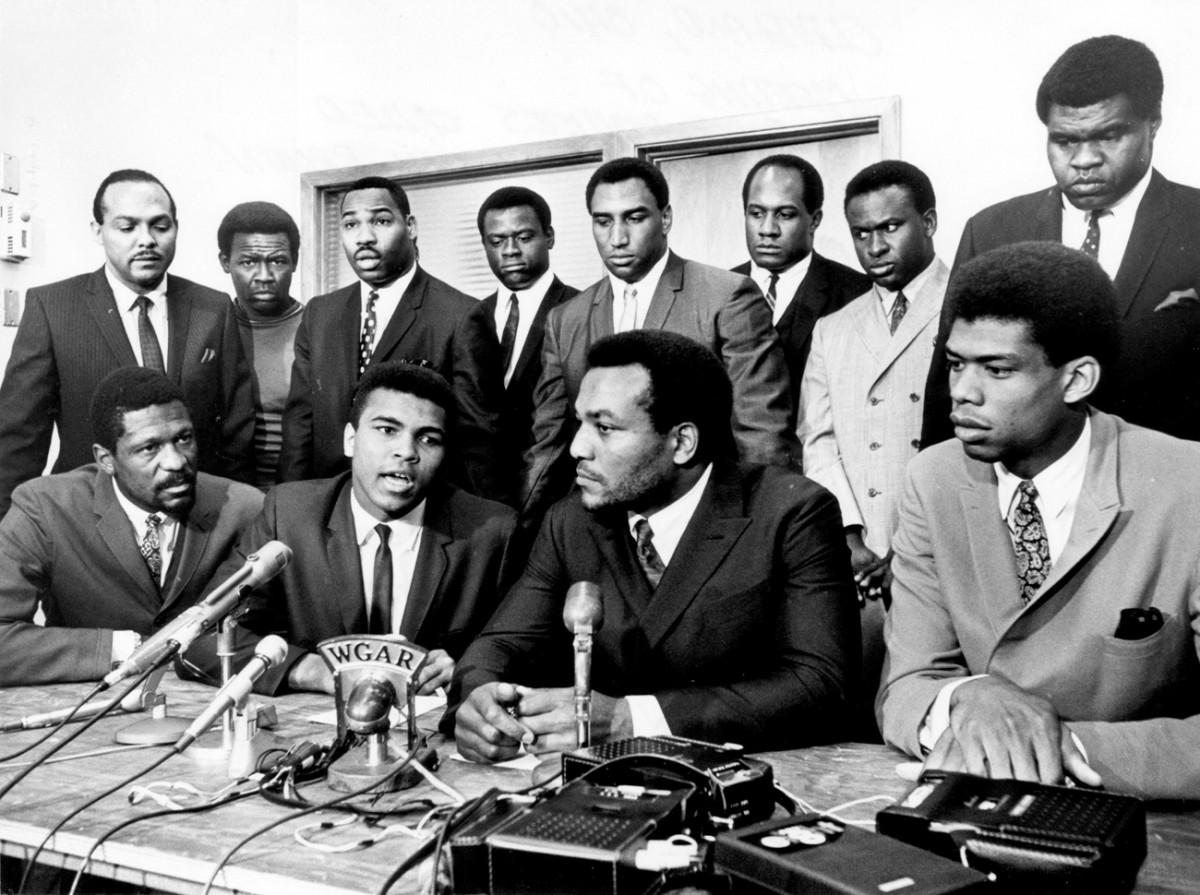

One day later Brown met with esteemed Sports Illustrated pro football writer Tex Maule on the set of the movie. Their remarkable exchange formed the basis for a single-source story in the July 25, 1966, issue of SI. In it Brown lays out the blueprint for an activist life beyond football, a life that had already begun with his formation of the Negro Industrial Economic Union (again, the language of the times), in which he involved many of his teammates. His movie career and his dispute with Modell accelerated his movement into a life he was already seeking.

Brown told Maule: “I could have played longer. I wanted to play this year, but it was impossible. We’re running behind schedule shooting here, for one thing. I want more mental stimulation than I would have playing football. I want to have a hand in the struggle that is taking place in our country, and I have the opportunity to do that now. I might not a year from now.”

And later this: “I quit with regret but not sorrow.”

In summer training camps around the league that year, players were stunned. “I heard it and I didn’t believe it,” says Dick LeBeau, at the time a Pro Bowl defensive back with the Lions. “He was much too good and much too young to retire. But I will also say that we weren’t sorry to see him go.” Ed Khayat, then 31, had come into the league with Jim Brown in 1957 and played against him 18 times in nine seasons with the Eagles and Redskins. He heard about the retirement while working out for one last season with the Boston Patriots of the AFL. “I thought it was impossible that Jim Brown was going to retire,” said Khayat. “His play hadn’t dropped off at all. I just couldn’t imagine it.”

Adrian Peterson would have to average 1,900 yards per season for the next three full seasons to match Brown’s per-game rushing mark, the 56-game hitting streak of NFL records.

Yet the sport moved quickly forward, as it does. The first season without Brown, the Packers defeated the ascendant Cowboys in Dallas to win the NFL title and represent the NFL in the first Super Bowl. The Browns remained an annual contender for nearly a decade after Brown’s retirement but famously have not win a title since 1964. Stories surfaced regularly hinting at a comeback, even as late as an absurd cover piece in SI in 1983 with Brown wearing a Raiders jersey. But he never did come back. He finished his career with 12,312 rushing yards in 118 games, a record that wasn’t broken until 1984, when Walter Payton went past him in 18 more games and 451 more carries. Brown’s career record of 104.3 rushing yards per game remains the 56-game hitting streak of NFL records. (Adrian Peterson, 30, would have to average almost 1,900 yards per season for the next three full seasons to tie Brown’s mark; it would take more than 2,500 yards for Peterson to do it in one year).

And all of this comes with a bold-faced ellipsis. On a summer morning at the Vikings complex in the suburbs southwest of the Twin Cities, Paul Wiggin, 79, sat grading videotape in the office where he works as personnel consultant for the team. Wiggin and Brown came to Cleveland the same year, 1957. “Jim retired two years before I did,” said Wiggin. “He could have played 10 years beyond me if he wanted.”

AT HOME

To reach Jim Brown’s house in Los Angeles, you drive uphill from the hustle of Sunset Boulevard on perilous, serpentine roadways that sweep past fabulous homes nestled into the hillside bramble, where a person’s address alone conveys a certain kind of success. Brown’s house is protected by a hulking metal gate—a relatively recent addition to the property—and sits at the bottom of a steep driveway. He lives here with his second wife, Monique, 41, and their two children, son Aris, 13, and daughter Morgan, 12.

Brown comes into the living room wearing Cleveland Browns sweatpants and a black Under Armour t-shirt. He is 79 years old, with graying stubble on his chin and cheeks, yet he retains the physical and emotional presence of his youth. His voice is deep and purposeful, though weakened and slowed by age, with the same hints of his Georgia roots that have always been present. He wants to know what route you drove to get here. You explain: Sunset to Laurel Canyon to Kirkwood, and then, frankly, it was too scary to recall the street names and there was this one time where you had to back down 200 yards to let a garbage truck pass. Brown laughs, a slow, halting series of Heh…Heh…Hehs. He does this often, the weary chuckle of a man who has seen and heard everything. “Ooooo,” he says. “That’s the hard way. When you leave here, just turn right and follow the yellow line down to Sunset.” You sense this is a message he has delivered frequently.

Brown’s home is a relatively modest two-story bungalow. But out through the tall windows in the living room is a sprawling, wooden deck that surrounds a swimming pool, and beyond the deck is a 270-degree panorama of Los Angeles, far below. On the right day you can see beyond the airport, beyond Long Beach and all the way to Catalina Island. Brown walked into the house in 1966 with his lawyer and a real estate agent, saw the view and bought it on the spot. “Told him, ‘I don’t even care what else is here besides the view,’” says Brown. “It’s a neat place. Served us well. A lot of history. A lot of people have been up here.” Muhammad Ali has been in this house. And Elvis. Louis Farrakhan. Huey Newton. Hugh Hefner. Johnnie Cochran. Michael Jackson. Jay Z. Gloria Steinem. Along with hundreds of troubled young men and gang leaders. A lot of people, indeed.

“Too many players stay too long. Too many players rely on the game. I retired because it was time to do other things.”

The guest list is a point of pride for Brown, but no more than this: “I came up here in 1966 and lived here since,” he says. “I never had to sell my house.” As if the world always sought to take away what he had earned.

You are here because Brown, on the 50th anniversary of his final season, and the end of a career unlike any other in the game’s history, has consented to an interview about that career. And let’s be frank, because each passing year moves us further from that career, so that one day it will be just numbers on a page, unseen by any living soul. But because this is Jim Brown, the discussion will veer off in many directions, much like the thick, gnarled fingers on Brown’s hands, the ones he once used to ward off tacklers. We will get there. But for now, there are the words he spoke to Tex Maule on a movie set in London in that summer of 1966. Words about regret, but no sorrow, and a harsh decision made at a young age.

Brown is sitting at a high glass table with tall chairs, like barstools. “I really wanted to leave on time,” he says. “Too many players stay too long. Too many players rely on the game. I retired at the peak of my career. I didn’t retire because I was broken down and slow. I retired because it was time to retire and do other things.”

You ask him about Art Modell and the $100 daily fines. Brown leans forward. “You want the real story?” he asks. “I had no bargaining power. But the only thing the Browns had over me was that if I wanted to keep playing football, I had to play for the Browns. But they couldn’t tell me I had to play football. Art was going to fine me for every day I stayed on the movie set? I said, ‘Art what are you talking about? You can’t fine me if I don’t show up. S---, I’m gone now. You opened the door.’”

Now you ask about the ellipsis. The what-if Jim Brown had played a few more years. Brown doesn’t like the question. He doesn’t like questions that lead him to answer in a certain way. He likes to frame his own answers into mini-speeches. “My ego is such that I did what I did on the football field,” Brown says. “If you like it, cool. If you don’t like it, that’s all right with me, because I can’t do it no more.”

THE PEERS’ PERSPECTIVE

In the summer of 1957, the best graduating (or eligibility-exhausted) college football players in the country gathered for a training camp in advance of the annual College All-Star Game, which pitted those collegians against the defending NFL champions at Soldier Field in Chicago. The concept seems preposterous now, but the game had been a tradition since 1934 and would be played until 1976. Brown had been the sixth player taken in the ’57 draft; two running backs were selected ahead of him: Paul Hornung of Notre Dame went first to the Packers, and Jon Arnett of USC went second to the Rams. Wiggin was there as the Browns’ sixth-round pick, a 242-pound defensive end. He was anxious to see Brown, and surprised at what he saw.

“He didn’t look like what I expected him to be,” says Wiggin. “I wondered if maybe [Browns coach] Paul Brown had told Jim to keep things under wraps.” (Brown would later write, in his 1964 autobiography with Myron Cope, Off My Chest, that he had been frustrated throughout the All-Star camp that coach Curly Lambeau had preferred Arnett to him. “[T]hat night Curly Lambeau made me,” Brown wrote). Wiggin saw a different player in Browns training camp. “We weren’t even scrimmaging, it was just thud [hitting without tackling to the ground],” says Wiggin. “But with Jim, you could feel the electricity of him going past you. You just knew that son of a gun was special.”

Wiggin remembers that Brown and some of the other African-American players were taunted by Lenny Ford, a 6-4, 245-pound defensive end who was nearing the end of his career and would later be voted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame (and who was also African-American). “Lenny would stand in he middle of the locker room and say, ‘Come on boys, gather ’round. Big Jim Brown here is going to tell you all how he scored six touchdowns against mighty Colgate.’ Jim would just say, ‘Lenny, leave me alone.’ ”

Brown remembers Ford differently. “Len took me under his wing,” says Brown. “He explained things about the game to me. He was older than me and understood things that I didn’t.”

“Jim Brown was a combination of speed and power like nobody who has ever played the game,” says LeBeau. “You just didn’t know if you were going to get a big collision or be grabbing at his shoelaces.”

Brown became an immediate starter at fullback. The position name is a misnomer; into the 1970s most NFL offenses used a split two-back backfield, with the backs positioned on either side of the quarterback or one back directly behind the quarterback. Unlike in modern offenses, both backs carried the ball, and both blocked. Brown rushed for 942 yards as a rookie and then four consecutive seasons in which he averaged 1,380 yards per season (three 12-game seasons and one 14-game season) and 110.4 yards per game.

Brown played at 6-2, 232 pounds, and history has catalogued him as a battering ram who pounded smaller players into submission. He did plenty of that, but Brown was much more. LeBeau was drafted by Cleveland in 1959, spent part of a training camp with the Browns and then was traded to Detroit. “Jim Brown was a combination of speed and power like nobody who has ever played the game,” says LeBeau. “Obviously arm tackles were not going to slow him down, but he was so elusive. If he got into the secondary, he was so good at setting you up and then making you miss. You just didn’t know if you were going to get a big collision or be grabbing at his shoelaces.”

Teammates remember a studious man, physically gifted, but also intellectually engaged. “Back then, the entire offense would watch film together,” says Wooten. “Jim would be right there with the offensive linemen. He would say ‘Guys, listen, I want to be able to hit this one right over here. And I want you to move it right over there.’ And we would block it exactly the way Jim asked. He had a great analytical knowledge.”

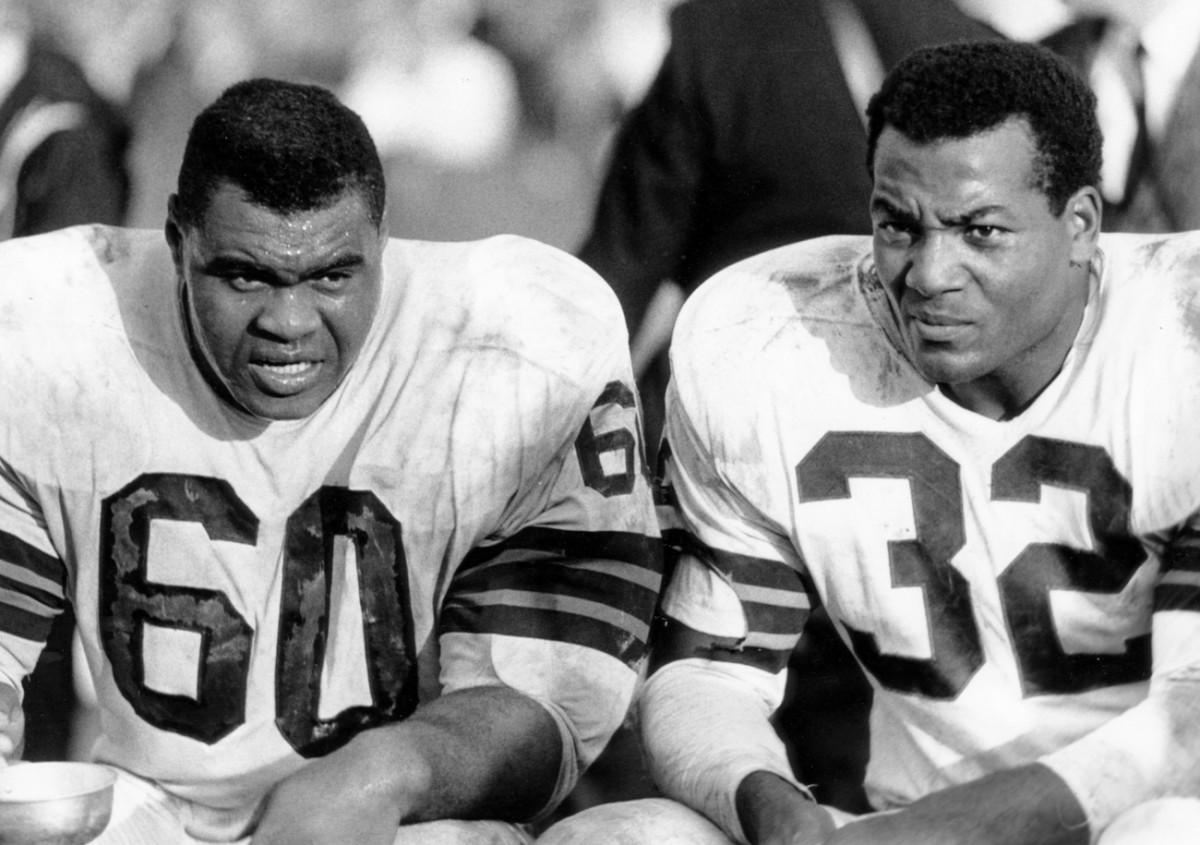

Brown also had a historically dominant offensive line with whom to share that knowledge. Paul Brown’s long-time offensive line coach was Frederick K. (Fritz) Heisler, a studious tactician who was among the first teachers of the system that came to be known as zone blocking. In Jim Brown’s early years in Cleveland, Heisler’s line included future Hall of Fame tackle Mike McCormack and future Hall of Fame coach Chuck Noll. Paul Brown was fired by Modell after the 1962 season, in part because of a player insurrection led by Jim Brown, who felt that Paul Brown’s offense had become predictable. Heisler stayed on under new coach Blanton Collier, and built the offensive line—tackles Dick Schafrath and Monte Clark, guards Wooten and Gene Hickerson and center John Morrow—that formed the foundation of the ’64 championship team. “People say Lombardi started ‘Run to Daylight,’ ” says Wooten. “Really it was Fritz Heisler. Go look at Jim’s long runs, the 50- and 60-yarders. Run to daylight, just like Lombardi’s teams, except it was Jim Brown.” In 1963, Brown rushed for 1,863 yards, breaking his own single-season record by 356 yards (albeit in 14 games, rather than 12); the record stood for a decade, until O.J. Simpson rushed for 2,003 yards. Wooten says, “Jim came out of a lot of games early in 1963. I wish we could have kept him in those games. The way we had it going, he would have rushed for 2,500 yards and nobody would ever have broken that record.”

Irv Cross, who would later gain fame as one of the first African-American analysts on network television, was an All-Pro cornerback who came into the league in 1961. He remembers facing Brown behind Heisler’s wall of linemen. “You would come up to defend the corner, and you cold feel the earth vibrating,” says Cross. “And you’ve got Jim Brown running behind those guys. I remember one play where I came up and Jim is behind John Wooten, and he’s got his hand on John’s back and he’s yelling at him, ‘Get him, Woot! Get him, Woot!’ Jim had moves like a halfback, and if you caught him, it took several players to get him down.”

Cross met Brown at the 1964 Pro Bowl in Los Angeles. “I found a solid, bright man,” says Cross. “He cared about the underprivileged in the world. He had a big heart. He also called me Herb. “Come on, Herb, let’s go. Come on, Herb, time for dinner.’ ”

To a man, Cleveland teammates remember Brown as uncommonly intense. Before games he would sit alone in the locker room, staring at air. “I had never been in the presence of anybody who prepared the way Jim did,” says Ernie Green, who was drafted in 1962 to play halfback alongside Brown. “Obviously Jim had the physique and the body to do it all. He could run over people, he could outrun people. But he would spend an awful lot of time visualizing the role he was about to play. And at all times, Jim enjoyed his own space in the world. You got to know him as well as you could, but there was a limit to that.”

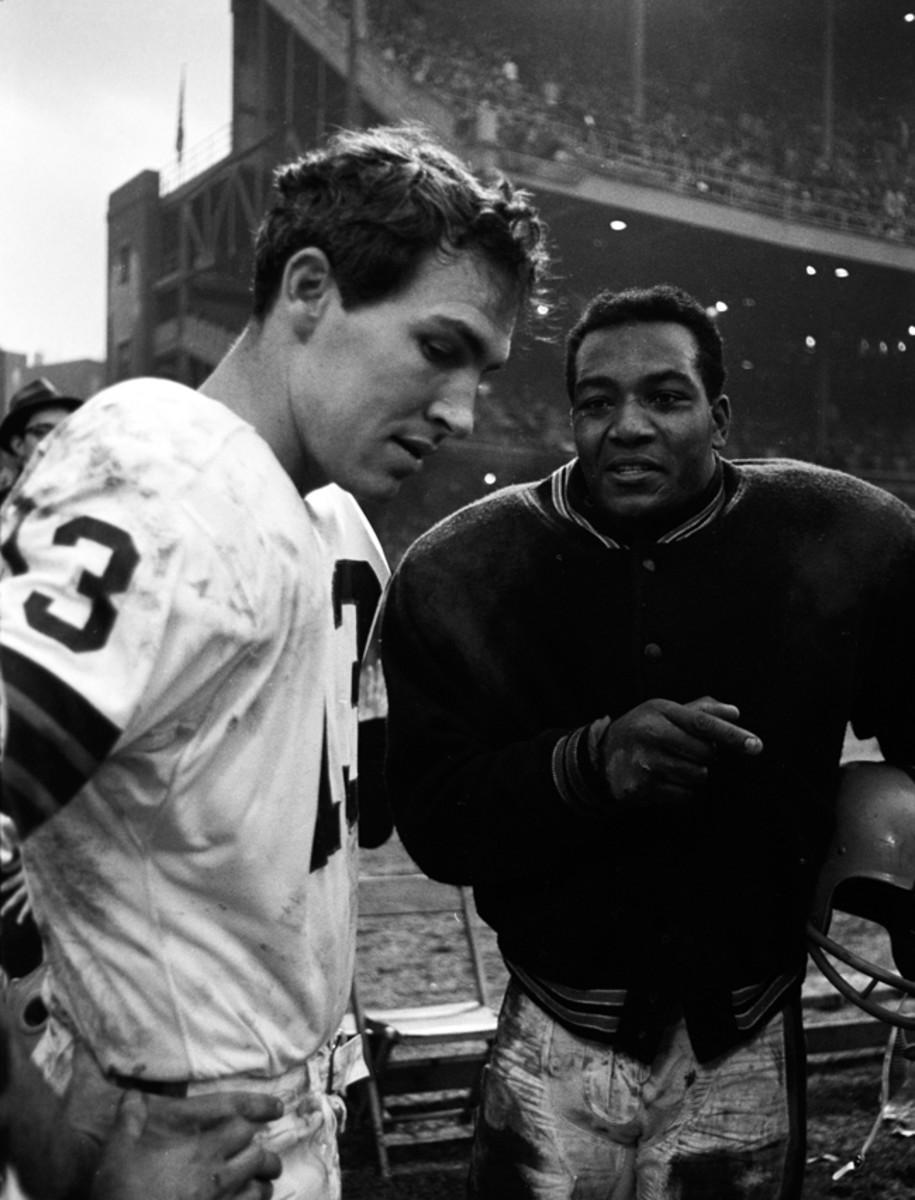

Before the 1962 season, the Browns acquired quarterback Frank Ryan from the Rams. The new QB was known as Dr. Frank Ryan, because he had earned a doctorate in mathematics from Rice, and he would play seven seasons in Cleveland, including three after Jim Brown’s retirement. Ryan threw three touchdown passes to Gary Collins in the 1964 NFL Championship Game, a 27-0 upset of the favored Colts and John Unitas. Brown ran for 114 yards on 27 carries in that game.

Ryan and Brown had a complex relationship. They were not close. Some of that was societal. “It was a different time,” says Ryan. “There was not a lot of white-black integration on the team.” Some of it was Brown’s personality—demanding, perfectionist, self-assured. In November 1964, the Browns’ championship season, they trailed Detroit in a game at Municipal Stadium in Cleveland. Paul Brown had used “messenger guards” to shuttle play calls in to Ryan, but when Collier replaced Brown in ’63, he allowed Ryan to call his own plays. However, on one third-down call, Collier sent in a play, which called for Brown to sweep around the right side, a very common play in the Cleveland offense. “We ran it, and Jim did not make it,” says Ryan. “And Jim was really pissed. He had wanted another play called. I don’t remember what play. But as we left the field, Jim jerked me around and yelled at me and well, I was just amazed that Jim would be so angry at me for running what the coach sent in, in a very critical situation.”

Ryan also recalled that during practice, if the Browns were executing sloppily on offense, Brown would often stage a protest of his own. “He would just slow down, instead of running full speed,” says Ryan. “It was his way of letting everybody know that he didn’t like the way things were going.”

Yet while Brown and his quarterback were not tight, there was a clear mutual respect. After a season-ending victory at Washington in 1963, Brown and Ryan were invited to the White House to meet with President Lyndon Johnson, who had taken office 24 days earlier, after the assassination of the John F. Kennedy. “We talked about race relations in America,” says Ryan. “It was a serious talk. And Jim was the reason I was there.”

Two years later, as the Browns were defending their NFL title, they were struggling at a home against the Redskins, three games from the end of the 14-game season. Collier sent backup quarterback Jim Ninowski onto the field to replace Ryan. But Ryan refused to come out and sent Ninowski back to the sideline. “I’m sure Blanton was horrified,” says Ryan. “But I was not coming out.” The Browns scored two fourth-quarter touchdowns (Ryan passed for one, Brown ran for another) to pull out a 24-16 victory. Traditionally, the players celebrated wins with parties at downtown hotels, but those parties where largely segregated. “That day, I was getting in my car in the parking lot,” says Ryan, “And I said to Jim, ‘Come on to the party with me.’ Usually the black players didn’t come to the party. Jim never did. But that night he came to the party. And I think he did it because he admired what I did on the field.”

Ryan pauses. “Jim liked to be in control,” he says. “But he was a tremendous football player. He was impressive in every possible way, just a superb athlete. We never really warmed up to each other, but I never lost my admiration for him.”

Many of the old Browns remember one play better than the rest. On the third Sunday in November of 1965, the Browns played the rising Dallas Cowboys at the Cotton Bowl. With the game tied, 3-3, in the second quarter and the Browns on the Cowboys’ three-yard-line, Ryan called 19 Stay, a flip to Brown on the left edge (with “stay” indicating that the back-side guard would not pull). Wooten picks up the narrative: “Jim takes the pitch and when we get out there to the corner, everybody is out there. The end, the tackle, the linebacker, the safety, the corner. Everybody.”

Green: “Jim just kept retreating until he’s about at the 10-yard line and there are eight guys around him.”

Wooten: “Jim just takes off and keeps running until he dives into the end zone. The last couple yards, he’s almost crawling, about a foot off the ground.”

Wiggin: “That run was beyond human capability. Just the sheer determination to get the ball into the end zone.”

Wooten: “I have that play on my phone. Sometimes I just call it up and watch.”

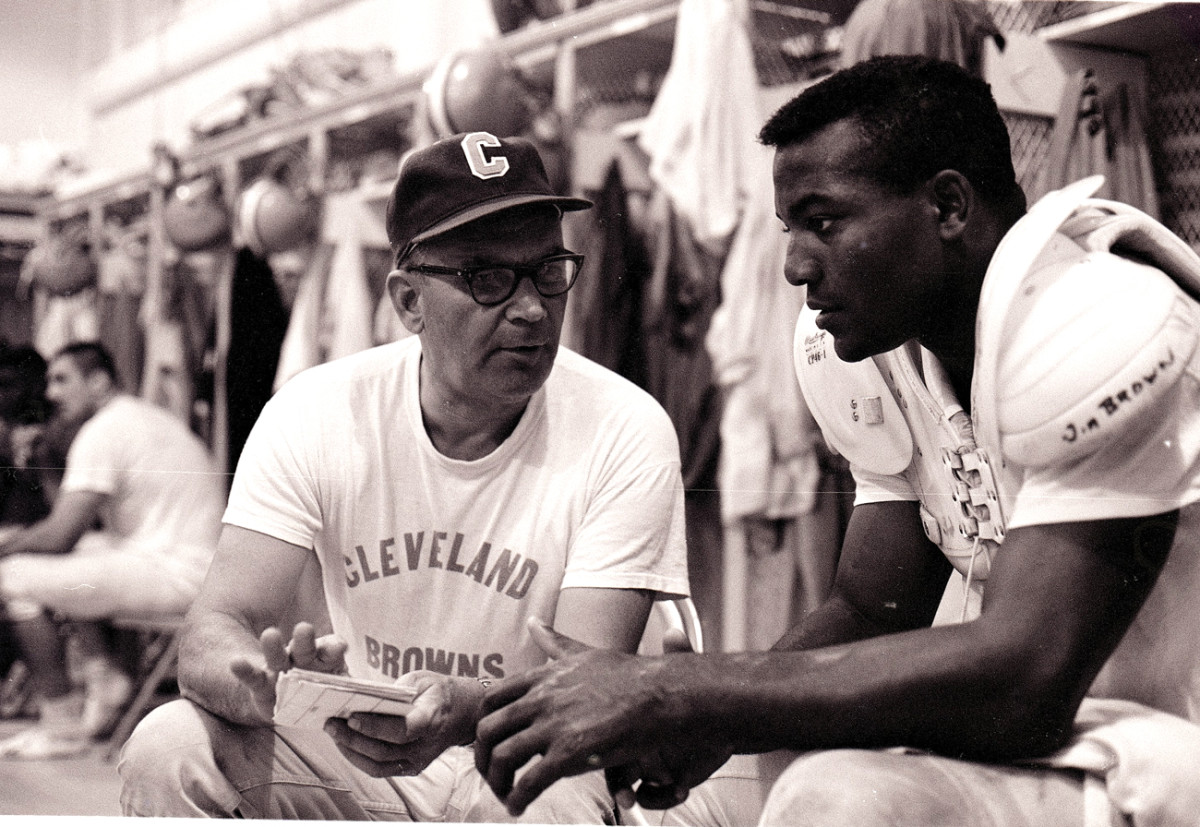

THE COACH’S VIEW

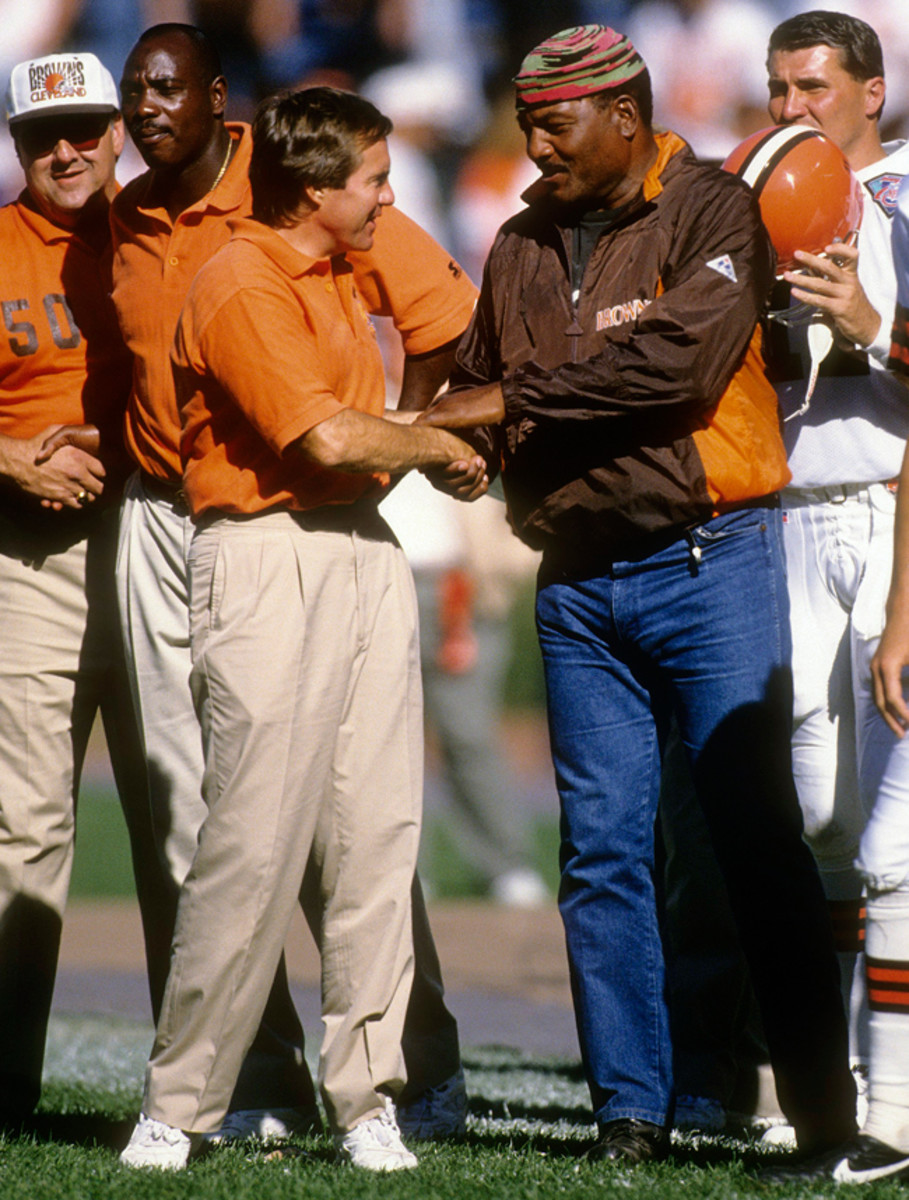

Before the start of a training camp practice, Bill Belichick sits on an equipment truck in the belly of Gillette Stadium, which is silent except for the sound of a forklift operating somewhere in the distance. Belichick first met Jim Brown in 1991, when Belichick was named coach of the Cleveland Browns. But he is a devoted student of football history; as a kid growing up in Annapolis, Md. (where his father was a coach at Navy), Belichick was a Browns fans. “Jim Brown was probably my favorite player,” says Belichick. “I loved the guy.”

At the start of his tenure with the Browns, Belichick brought Brown back to the franchise and into the meeting room with his running backs. The result was disastrous. “It was embarrassing,” says Belichick. “They had never heard of Jim, didn’t know who he was. I mean, this was f---ing Jim Brown, the greatest football player in history. That was my mistake. After that I made sure to educate the players ahead of time, to explain who Jim was, show them some highlights.”

On this day, Belichick is at first hesitant to break down Brown’s game. There is apparently no real game film of Brown in existence. The Browns have none. NFL Films has none. CBS, which broadcast NFL games during Brown’s career, was unable to provide game film when asked. There are highlight packages available on the Internet and also one fairly complete reel of the 1965 championship game, skillfully cobbled together from various sources. These highlights comprise most of the Brown canon. The rest is lost to time. “I never coached against Jim,” says Belichick. “I’ve seen the same highlights everybody else has seen, and they are awesome. He was big, he was fast, he was powerful, he had great hands. Everybody knows that. I don’t know that I can provide any unique insight.”

At the start of his tenure in Cleveland, Belichick brought Brown in to meet his running backs. “It was embarrassing,” Belichick says. “They had never heard of him, didn’t know who he was. I mean, this was f------ Jim Brown, the greatest player in history.”

But of course he can. Belichick possesses one of the best football minds in history. He does not see what everybody sees, even in highlights. You prod him forward. Brown was called a fullback. But was he a fullback? “He was a combination of a fullback and a halfback,” says Belichick. “He had great power and leverage, but he was also very elusive in the open field like a halfback. His quickness, straight-out speed and elusiveness were all exceptional. And he was all of 230 pounds. He was bigger than some of the guys blocking for him. I mean, they might have weighed more, pumped up, but Jim’s hands, his forearms, his girth. He was bigger.”

Brown’s place on the evolutionary timeline of the game is a significant factor in his legacy. He did not play the same position that Adrian Peterson plays. “There was no I Formation in the 1960s,” says Belichick. “There were two-back sets with the backs lined up flat. Jim was five, maybe five-and-a-half yards behind the quarterback. Now guys are six-and-a-half, seven yards, at least. So Jim had to read things much quicker, but he also got to the hole much quicker.

“The last guy in the league, that I can remember, who lined up that close to the line was [John] Riggins, with the Redskins,” says Belichick. “Franco Harris, too.” Riggins played from 1971 to ’85; Harris from ’72 to ’84. After that era, running backs lined up deeper, as many do, now. “Guys like Chuck Muncie, Eric Dickerson, O.J. Simpson,” says Belichick. “The game shifted to a deeper positioning of the running back.”

You ask Belichick for comparisons. Dickerson maybe? He was 6-3, 220 pounds. “Dickerson was more of a straight-line runner,” says Belichick. “Not that he didn’t have great skills. But Jim moved like a 185-pound runner.”

Adrian Peterson (6-2, 218)? “Another guy who is explosive at the line and pulls away,” Belichick says, “but Jim had so much short-area quickness. Quick feet, lateral movement. Franco Harris had some of that, but less speed. I’m not saying Franco was slow, but he didn’t have Jim’s breakaway speed.” Historians looking for holes in Brown’s legacy often note that he played against much smaller defenders. It’s true. But Belichick hammers the point that Brown’s lateral quickness, agility and intelligence are evergreen qualities.

During Belichick’s tenure in Cleveland, Brown came to counsel the team’s running backs, as a sort of adjunct position coach. It was in this role that the same analytical mind that Cleveland teammates had seen three decades earlier presented itself. “He is incredibly perceptive about running the football,” says Belichick. “Tremendous understanding of how to beat defenders, how to attack their leverage to give them a two-way go. He has great insight into what a runner sees, and he could explain it in very simple terms. Here is the tackler, here is your leverage point.”

More than a half-hour has passed. Belichick has walked from inside the stadium to the practice field, to the applause of Patriots fans ringing the facility. It is clear that he has not only great respect for Brown as a player, but also personal affection. Belichick has visited prisons with Brown and supported his work with at-risk youths. “He’s a guy who has a handle on life,” says Belichick. “He’s worked with the worst of the worst, the baddest of the bad, and he can get them under control. Really an incredible man. I hope people understand that.”

One last question: One day earlier you had asked Dick LeBeau this question: If a 22-year-old Jim Brown were drafted into the modern NFL, would that player be effective? “He would be absolutely dominant,” says LeBeau. “There are so many more ways to get him the ball in space, and when Jim was in the open field, you had a problem.” (Wiggin, who studies athletes for a living, says, “The game evolves. I was a player for my time. Jim Brown was a player for all times.”).

The same question to Belichick: If a 22-year-old Jim Brown… Belichick interrupts. “Oh my god….”

DESCENDANTS

Adrian Peterson trundles out of the Vikings’ practice facility locker room and into the sunlight before extending his right hand and crushing yours like a ripe tomato. Before missing all but one game of the 2014 season (under suspension after his arrest on child abuse charges), Peterson was the most obvious modern parallel to Jim Brown: a dominant running back with size, speed and power (putting aside, for a moment, Belichick’s more specific evaluation). Brown says so: “Adrian is one of the best that’s come along. He has the full physical package and the runner’s attitude.”

Peterson has never seen Brown in action, so you hand him a tablet loaded with highlights. Peterson takes the tablet, pulls a towel over his head to block the sun’s glare and begins watching. Number 32, you tell him. Peterson watches the screen for nearly four minutes, saying nothing. Then he begins talking: “Physical player,” he says. “Relentless. Great vision. Great balance. Great effort. Awareness.”

Peterson hands you the tablet back and nods. “What do I see?” he says. “Quick feet and great balance. He bounced off defenders, but he also cut around defenders with his quickness. The power is obvious. He drove one guy back about five yards and just kept going. I mean, yeah, man, he was one incredible running back.”

When Peterson was growing up in Texas, he looked up to Barry Sanders, Emmitt Smith, Terrell Davis. “And Eddie George,” says Peterson, “because I was a tall back, and he was tall. But my dad would talk about Jim Brown, so I heard the name.” In 2008, after Peterson won his first rushing title with 1,716 yards, The Sporting News arranged for Brown to “interview” Peterson at Brown’s home in those Hollywood Hills. “Beautiful view, man,” says Peterson. “And around Jim, I stayed pretty quiet for a while. He’s a straight shooter, scholarly guy. Cares about his people. Without a doubt, there’s a presence when you are around him.”

Peterson doesn’t know the whole story, how Brown retired at age 29 after nine seasons. (Peterson is 30, in his ninth season, although he played just that one game a year ago). And how Brown had rushed for those 4,853 yards in his final three seasons, more than Peterson has gained in any three consecutive seasons. “Wooooo, fifteen hundred in his last season and then he retired?” says Peterson. “I mean obviously he didn’t let football consume him. But if he played four or five more years? His records. I guess that’s the scary thing, there’s always that open space to wonder about if he kept playing.”

You tell Peterson what Belichick said about Brown’s elusiveness and small-area foot quickness being more effective than his. Peterson picks up the tablet and watches a little more. He hands the tablet back and laughs. “I think,” he says, “I would have to agree with that.”

“I wasn’t dominant, not like Jim,” says Barry Sanders. “I can’t think of anybody I would put ahead of him.”

Barry Sanders’ career is the one that most closely parallels Brown’s. The Lions great rushed for more than 5,000 yards in his last three seasons and retired abruptly at the top of his game after 10 years in the league. Sanders has known Brown for many years, visited his L.A. home and played golf with him; Sanders’ father, William, was a fan of Cleveland and Jim Brown (“He would wear a Cleveland Browns jacket to my Detroit Lions games,” says Sanders), and Barry introduced the two men before William Sanders’ death in 2012. He is an unqualified fan.

“Jim was a dominant specimen,” says Sanders. “He was physically strong but also just a beautiful runner. He had quickness, he had vision for finding open space, but he could also run you over. When you talk about the best players ever, who would you put ahead of him? He was dominant. I know I wasn’t dominant. Not like Jim. Jerry Rice, maybe? Lawrence Taylor was dominant. I can’t think of anybody I would put ahead of him.”

Sanders has a unique perspective on the what-if, having left the game just 1,457 yards short of Payton’s career rushing record, since broken by Emmitt Smith. “It’s fine to consider what Jim would have done,” says Sanders. “There are times when I think about what it was like out there. I don’t know if that translates into, ‘I wish I played longer.’ I played the right amount of time. I think that’s true with Jim, too.”

BACK HOME

You began with an apology of sorts to Brown. He played professional football for nine years and has lived a full, vibrant (and frequently controversial) half century since. Nine years versus 50. Yet you came to talk about football. Brown knew this, and through his wife, he agreed to the meeting. “It’s your interview,” says Brown. “So the topic is up to you.” But in truth the topic is never up to you. The topic is always up to Brown. “I want my points to be my points,” he says. “I want my voice to be my voice.” (Brown’s life is not unexamined: He wrote autobiographies in 1964 and 1989; journalist Mike Freeman wrote an unauthorized biography in 2007; Spike Lee made a feature-length documentary in 2002.)

Yet the voice wants something understood. “God gave me a combination of skills,” says Brown. “I was 232 pounds, six-feet-two. I had enough strength to be uniquely physical. And there are times when the game depends on that physicality. We called those ‘attitude’ plays. And that’s where you go at a man to get one yard and you want to tear him up. But did I want to hit people? Of course not. My job as a running back was to get as much yardage as I could get, and if I could do that without touching a single defensive player, it would not mean a doggone thing to me. It was never my job to see how many guys I could hit. That was Jim Taylor’s job, or somebody else. Heh… heh… heh. For me, it was daylight first.”

“I don’t care if some person says I was the best this or that. I like the respect I get when I move among other players. I do like that.”

And this: “I studied the game.” Like his teammates said. Like Belichick said. “I studied my opponents, and I studied other running backs. I had an ego, but I didn’t have so much talent that it kept me from respecting other people. There was a guy named Don Bosseler [a fullback who played for Washington from 1957 to ’64]. He would throw himself into the air from the 1-yard line. I tried it a couple times and was not successful. Heh… heh… heh. So I studied the films, and I saw that he was not just jumping. He was studying the linemen and then making a decision whether to jump or not jump. I learned from Bosseler. You have to study everything.”

On the one hand, Brown makes clear that he was ready to leave football. “I had a full dose,” he says. Yet as he sees the game from further away, he views it more affectionately. “I have a greater appreciation for it,” he says. “It gave me an opportunity to express myself on a personal level. As a black man in America, there were certain disadvantages to my existence. Football gave me certain other advantages. It has been a major part of my existence.”

Still, he will not be judged. “I did the best I could, and I played hard,” he says. “I don’t care if some person says I was the best this or best that. I like the respect that I get when I move among other players. I do like that.”

There was a time when Brown could be counted on to denigrate the modern NFL, allowing that button to be pushed and supplying a brief homily on running backs who too often ran out of bounds (Franco Harris was on receiving end of many such rebukes) or made too much money. He doesn’t go there quite so often nowadays, expressing great admiration for Peterson and respect for Jamaal Charles, whom he admits to not having seen often enough. He attended the memorial service for Junior Seau in 2012, helping connect generations. If he moves and speaks just a little more slowly at 79, his thoughts remain lucid and sharp. He occasionally forgets a name, but to a layman there is little obvious evidence of the cognitive damage that afflicts so many former players. Perhaps nine years was long enough, indeed.

The NFL remains mired in a crisis on domestic violence. Five times in Brown’s life he has been accused of violence against women, though none of those charges were proved in court. Most recently, in 1999, he was charged with vandalism and making a terrorist threat after smashing the windows of Monique’s car during an argument. (The terrorist threat charge came because Monique told a 911 operator that Jim had threatened to kill her, a charge she later recanted.) At the time, Brown was 63 and Monique was 25; they had known each for four years and been married for two. The couple went public together and fought the charges in a series of media appearances. Jim was found guilty on the vandalism charge, and rather than accept any plea bargain he served six months in prison.

Monique says now, “We had an argument, and Jim damaged his own property. There has never been any domestic violence in our home. He has talked to our son. It is not something that Jim would ever tolerate.” She says that Jim has “settled into a wonderful family life.” (Thought she rejects the verb mellowed.) Aris, an eighth-grader, loves to play lacrosse, the game at which some think Jim was the greatest player in history. They play catch in the driveway behind the house.

When you ask Brown how he would counsel young players on how to treat women, there is a pause. Then the laugh. “I know what you’re trying to get at,” he says. “There is no excuse for violence . There is never a justification for anyone to impose themselves on someone else. And it will always be incorrect when it comes to a man and a woman, regardless of what might have happened. You need to be man enough to take the blow. That is always the best way. Do not put your hands on a woman.”

At the end, you ask him to watch himself. Brown agrees. You open your laptop’s screen and begin streaming highlights that must have seen hundreds of times, but perhaps not in a long time. As the plays unfold, Brown goes silent, offering only occasional comments. He smiles, almost perceptibly.

In one sequence he outruns a Lions defensive back and compliments the opponent.

In another, he spins away from a Washington defender, only to be drilled in the back by another. “Lucky I didn’t get hurt there,” says Brown, stroking the whiskers on his chin.

He scores easily against the hated Giants. “ Walked right in,” says Brown. “Good blocking.”

After 15 minutes, the videos are exhausted. Outside the windows and far to the west, the sun is falling toward the Pacific. Another guest has arrived in the Brown household. “Thank you for showing that to me,” says Brown. “It’s funny. I keep seeing things I could have done better. Things I could have done differently. That’s the way it is with football.” One last laugh. Heh… heh… heh. “That’s the way it is with life, too.”