A Life in Journalism

This week at The MMQB is dedicated to the life and career of Paul Zimmerman, who earned the nickname Dr. Z for his groundbreaking analytical approach to the coverage of pro football. For more from Dr. Z Week, click here.

The first time I read Tom Wolfe proclaiming that the New Journalism and Personal Journalism were something of a modern phenomenon, I felt like asking him, “Did you ever hear of Rudyard Kipling?” When I read, not too long ago, about the revolution in sportswriting that introduced the freshness of penetrating, iconoclastic observations and in-depth quotes and probing interviews, my only reaction was that the people who actually believed this stuff didn’t understand much about the history of the profession.

There were real phrasemakers in the old days, and when I was a kid, I used to cut out their snappers and one-liners and keep them in a big notebook. There was punchiness and wit and sparkle that we don’t see too often nowadays. Not that the old-time sportswriters were that much better, day in, day out, but when one of them connected on something, it went out of the park.

Have you ever heard of Frank Graham? Columnist for the New York Sun. Nobody ever put it better, referring to the athlete on the verge of retirement who all of a sudden feels the need to talk to you about “an exciting new project I’m involved in.”

“They learn to say hello,” Graham wrote, “just when they should be saying goodbye.”

I grew up with this kind of stuff. It was my English Lit seminar, my exploration into the classics. Graham, again, covering the Max Baer-Tony Galento fight in Jersey City in 1940, and I would have to call this my favorite lead:

“They rolled the clock back last night and two cuckoos jumped out.”

I can quote you parts of that story. The fight ended when Galento couldn’t come out of his corner for the eighth round.

“I can’t breed,” was Graham’s quote for Two Ton Tony.

And post-fight, Baer, who was known as The Clown Prince, did a little waltz around the ring with a dwarf who was part of his ringside entourage.

“Three cuckoos,” was Graham’s closing line.

My own career? Well, I wish I could put a definite beginning on it, and tell you, yes, this is where my 48-year run as a sportswriter got its start, and paint one of those misty, moody pictures for you; racehorses in the early dawn, the slap and crack of pads during a miserable, sweaty scrimmage, the piercing shouts of high school kids during a local wrestling tournament. But no, it began with a series of catch-can assignments for the Sacramento Bee, the high schools, naturally ... you always began a career with high school sports in those days ... but there was also the hustle of carving out a beat for myself when one didn’t exist. A local hockey league played on an undersized rink among teams with names like the Rexalls; junior tennis, watching a pair of stern-faced 12-year-olds staring each other down.

I talk to kids two years out of school nowadays who tell me they’re desperate to write sports, and then they lay out their agenda; the NFL would be nice, and of course, major league baseball, and if they have to cover the fights, well, they’ll do it as an accommodation. A few times when I’ve offered advice about a certain word, humility, I’ve been told, “I’m sure it was easier when you broke in.”

Easier, yeah. A few weeks short of graduation from journalism school the chilling realization struck me that no one wanted to hire me, despite the fact that the Columbia J-School was supposed to be my ticket anywhere. I found a copy of Editor & Publisher and looked up newspaper addresses. Then I wrote 64 individual letters to sports editors around the country, explaining why I was especially suited to cover sports in his area. Eventually I got four replies: no, there’s nothing available. Sixty stiffs. Then I visited every newspaper office in the New York area, seeking an audience with the sports editor. Two saw me, a guy named Zeliner at Newsday in Long Island, and Bob Stewart at the New York World Telegram & Sun.

Actually he remembered me as a football player, at Columbia, and he pulled out a five-year-old squad picture that I was on. He told me to keep him posted.

Then I packed up my ’57 VW that I’d bought in the Army in Germany, drove out to Seattle, where I had a friend to stay with for a few days, and headed down the coast, town by town, coming in cold, asking for work. I made it as far as Sacramento and the Bee. Someone had quit the day before I showed up.

“How’d you find out so quickly?” Bill Collins, the sports editor, asked me.

“The Columbia Journalism School keeps us informed,” I told him.

I think that’s what swung the job for me, the lurking suspicion that I was backed by some kind of mysterious information network.

She was posing at the station, very prettily, with a stylish dress and hat and veil, in front of a background of bleak desert. And in that barren background, two dogs were humping. I laughed every time I looked at that thing.

My first newspaper job, on the Bee, was, in retrospect, a dream job for a young writer just starting out. The paper was scrupulously honest. You were held strictly accountable for every quote, every fact. There was an odd, old-fashioned, conservative strain to the paper, too. The saying around the city room was that the style guide was written by someone who had been dead for 50 years, old C.K. McClatchy, the founder and owner. There were some weird rules it was necessary to remember. You weren’t allowed to use contractions. The old man just hadn’t liked them. Make that had not liked them. This was a stunner, the idea of filling your story with “had not,” and “can not,” and “did not,” but that was the rule. Also, you could never write that it was hot in Sacramento, and that included all derivatives. It was “warm,” even though people were dropping from the heat, which could get up to 110 degrees. I remember covering a junior tennis match involving 10-year-old Rosie Casals on one of those blistering days, and I tried to make it a mood piece, the two little girls running around in that withering heat, etc. That’s before I knew about the rule. In the paper, it came out, “withering warmth.”

When you were on the road, you always had to dateline your story with the name of the county attached, after a comma. The standing joke was that a gunman jumps into a cab in downtown Sacramento, sticks his gun in the driver’s ribs and says, ‘Roseville, comma, Placer County.”

The Bee’s city desk fascinated me because of the collection of characters who manned the slots. My favorite was a real old-timer named Wayne “Slick” Selleck, who actually wore one of those green eyeshades that were known as the trademark of ancient newspaper men. Slick had some great stories about the old days, but the best thing he had was a scrapbook he had compiled of the bizarre and outlandish, much of which was of a smutty nature. My favorite item, out of a spectacular collection, involved a large photo that led the features page of the Bee, mid-1920s. It showed a movie actress who was passing through Sacramento by train. She was posing at the station, posing very prettily, with a stylish dress and hat and veil, in front of a background that was a bleak desert, which I guess was much of the area in those days. And in that barren background, two dogs were humping. I laughed every time I looked at that thing.

I was single and caught up in the excitement of actually doing newspaper work. I was making $85 a week, and it seemed that I always had money in my pocket. My little duplex in North Sac cost $61 a month, later lowered to $60 by my Polish landlady because I was quiet and paid on time. My big meal of the week was the $2.99 All You Can Eat Roast Beef and Shrimp Newburg special at Sam’s Rancho Villa in Carmichael. It would hold me for 24 hours.

I covered tennis and got to love the sport. I did a serious mood piece on Rosie Casals, aged 10, outlasting Leslie Abrahams, 13, in a three-hour marathon in the Central Cal juniors, the blistering heat, uh, warmth, sand flying, getting in their hair, their eyes, the two kids racing around the court, tears streaming. The best match I ever saw. I remember interviewing little Rosie afterward, a tough Mexican-American kid, going around to the tournaments with her white-haired father, the two of them shunned by the fancy clubs, which wouldn’t put them up overnight, having to sleep in their old jalopy of a car. “It was the gear shift that killed me,” she said.

Every once in a while I’d get on a crusade. The McClellan Air Force Base football team was one of them. In 1959 they went unbeaten in the regular season. They were an active, overachieving bunch of guys who hadn’t played anybody. Their record looked impressive, with victories over teams such as Santa Clara and San Jose State. The problem was, it was the jayvees, not the varsities of those schools, that they had beaten. But their PR releases didn’t mention that part of it.

I got on the directors of the armed forces sports programs for ignoring this eager bunch of hardworking guys. “They’re unbeaten ... they deserve to play in the Shrimp Bowl,” I wrote in many different ways. The Shrimp Bowl in Galveston was for the Service championship. Someone must have listened, because all of a sudden McClellan was invited. The opponent was Quantico, typically the Notre Dame of the armed forces. It was rumored that Billy Vessels, the former Oklahoma All-American, was on that team. There were other college stars, a lot of officers who’d been in ROTC programs in school. Quantico was loaded.

The final score was 90-0. You could look it up, Shrimp Bowl, 1959 season. Oh my God, had I done that? I was at the airport to meet the McClellan team on its return from the game. It looked like a troop transport bringing back the wounded. Guys were coming out in casts, on crutches, all bandaged up. I talked to one poor guy who had his arm in a sling. “When we came out for the warmups, they had so many guys that they circled the entire field,” he said. “I thought, ‘Uh oh, we’re in trouble.’ ”

* * *

I had a lovely way of life in Sacramento. The living was easy, so easy it scared me. I can work here and grow old here and die here, and nobody ever would have heard of me. I had reverted to a New York way of thinking. Then Bob Stewart of the N.Y. World Telegram told me to come back and write schoolboy sports for them. My co-workers on the sports staff gave me a Duncan Hines Guide to Dining Out in the U.S. as a going-away present, and I planned my trip accordingly, in an attempt to gain back all the weight I had lost in Sacramento.

I found a two-room apartment on West 106th St. for $75 a month, a step up from my North Sacramento duplex, but then again I was making more money, too, something like $98 a week. It was summer, so I worked the night desk until the high schools began. I’d write headlines, read copy, write cut lines, the same stuff I’d done, off and on. The best overline for a picture that I ever wrote was not used. I’m still bitter about it. Del Webb, co-owner of the Yankees, had just gotten married, and we ran a picture of him and his wife stepping off the plane. My kicker line was: NEWLYWEBBS. Marty O’Shea, the assistant night editor, killed it. Demeaning, he said. I begged, pleaded. No dice.

Around midnight every shift a welcome figure would arrive, John Condon, the publicist from Madison Square Garden. He’d arrive with his regular bribes for the nightside guys, the real power elite who could get stuff into the paper. Sandwiches from the Stage Deli, big ones, huge, just the things you dream of. A big cheer would go up when John arrived. Talk about smart PR men. He got just about anything he wanted in the paper.

The night sports editor was Sal Gerage, a young guy who had gone to Seward Park High School with Bernie Schwartz, a.k.a Tony Curtis, the actor. A brilliant desk man, that was Sal, with a real flair for nicknames. Phil Pepe, who’d been the schoolboy writer before me, was Bugs Bunny, for his prominent front teeth. Bill Bloom, the tiny little man who wrote horse racing, was The Japanese Admiral. I was Tarzan. I think I was the only one who actually liked my nickname.

I’d been there about two weeks when I discovered a wonderful thing. Nightclubs were very big in New York, back then in 1960. The Telly covered hundreds of them, thousands. There were always a couple of nightclub reviews in the paper every day. Midtown New York, little joints in the Village, in Brooklyn, Queens, yes, there was something to say about each one. A curious thing was that the pieces carried bylines of many different people. How big was the staff anyway?

Then I found out that anyone could cover a nightclub. Just had to ask. You got no pay for it, but you were comped on food and drink for you and a companion. You could praise the show, rip it, whatever. They didn’t care. Just mentioning it was the thing. Wow! Talk about planning a sensational date. I mean you could interview any of the performers. “My date the night club reviewer.”

I became a regular. Never in my life had I had such an assortment of dates... budding actresses, a swimsuit model, you name it. Then one day Robin Turkel, our guild rep, talked to the entertainment department and demanded that we get paid for our reviews. Now, I’m a strong union man, always have been, but... “Jesus, Robin, just leave it alone, OK? We’re doing fine.” Nope, fair’s fair, he said. No overtime, no night club coverage. Fine, said management. Goodbye and good luck to the sweetest deal anyone ever had. You’ve never seen so many dates abandon a human being in your life.

The urge to be clever is one that will destroy you; the straining will blow you apart.

I had a great time covering schoolboy sports. I had to pick an All-Met football team every year, encompassing the city and the huge surrounding area of Westchester County, metropolitan New Jersey and Long Island, I was always on the road, seeing games live, watching films with the coaches, scouting practices. I had huge books of charts. In short, I was doing what I later did in my NFL coverage for all those years, and I was in dog heaven.

After the season we threw a dinner a Mamma Leone’s on 48th St. for our All-Mets. Larry Robinson, who covered college football as well as golf, got college players to attend and sit with the kids, Joe King got Giants, Larry Fox got Titans from the AFL. The entertainment section got a comic to come and entertain every year. The best was Bill Cosby. The kids loved him, but when we tried to tell him afterward how much we appreciated his coming there, he turned his back and told his agent, “Let’s get out of here.”

When Richie Kotite became coach of the Jets in 1995 and I was out at their camp one day, he fished in his wallet and pulled out a little laminated newspaper clipping. It was something from my All-Met piece in 1960, the capsule comment I had written on him: “Headed for the big time.”

I remember driving down to Poly Prep in Brooklyn in the rain and watching him against Horace Mann, my alma mater. “I never forgot that,” he said, “and I never forgot that dinner at Mama Leone’s.”

I gradually moved up the ladder, from schoolboys to college sports, with an occasional look-see into the professional arena, a fairly smooth progression with one glitch. Gerage, our night editor, had been enamored with an old Tim Cohane column of the early 1940s called Frothy Facts. He wanted to see it revived, and he decided I was the guy to revive it. I was told to be bright and sparkling and lively.

Well, the urge to be clever is one that will destroy you; the straining will blow you apart. I look back on those columns now through fingers spread over my eyes. The less said the better. Occasionally a laugh or two, but clearly I was not ready for that kind of action. The worst thing was what it did to my ego. Listen, everybody, I’m a columnist now! But there was one good element involved with the venture. At the bottom of each column, which appeared three times a week, was a little feature called: 10 Years Ago Today, and then 25 Years Ago Today.

I got the items from our morgue, which had, in addition to old World-Telegrams, other papers as well. I had my own desk set up back there in the library. I’d get interested in murder trials of the 1930s, war news, the pennant race of 1938. I’d start following old comic strips day after day ... Terry and the Pirates, Dick Tracy, etc. I’d go in after lunch, and before I knew it the night crew was coming into work. I was lost in a time warp. That’s where I found those great Frank Graham one-liners. I collected them, put them in a notebook.

After a while I started going back even further, into the 1920s. I wanted to see what Paul Gallico was like before he quit in 1936 and wrote Farewell To Sport, which had been my bible. I wanted to read Grantland Rice day to day. I discovered an interesting thing. The old-timers were streak hitters, some stuff great, but occasionally they’d take a pass during a lull and concoct a whole piece about, say, the release of the weekly football statistics.

Rice was a hell of a yarn-spinner, though, and how many of today’s sportswriters, forgive me, media (God, how I hate that word) would pepper their stuff with verse as he did? I particularly liked Rice’s story about when he was at the Yale Bowl, covering a football game, and afterward, as the writers were sitting in the press box, banging out their stories, a young guy, working hard to capture the mood, pointed at the setting sun and asked, “Is that the west over there?”

“Son,” Rice said, “if it ain’t, you’ve got yourself a hell of a story.”

* * *

The New York sports scene was a lively place in the 1960s. The Yankees were riding high. I’d pick them up on an occasional road trip, and it was a tough assignment for a young writer. Arrogance ran high in that locker room, one-word answers from the famous vets, the sneer, the cold shoulder. The good stuff was saved for the older beat writers, who would constantly remind them who the guys were who took care of them. I grew up a combined Giants and Yankees fan, but when I covered the Yanks I would hope that they’d lose so I could get my story from the other team’s locker.

I remember flying in with the club on a road trip one night, around the time the Yankees started to go bad, and sharing a cab from LaGuardia into the city with Vic Ziegel of the Post. The cabbie asked us what the big group was and we told him it was the Yankees.

“Oh yeah?” he said. “Are you guys Yankees?”

“I’m not,” Vic said, “but he’s Clete Boyer.”

“Yeah?” the driver said, turning half around in his seat. “Clete, I know you ain’t been going so good, but the cabbies are behind you, Clete, I just wanted you to know that, we’ll always be behind you, Clete.” And so it went, all the way into the city.

He let me off first. Vic told me that the cabbie watched me walk all the way into my apartment house, and then shook his head.

“Clete’s gained an awful lot of weight,” he said.

The Mets? Ah, now that was an assignment. You’d kill to cover the Mets and Casey Stengel. I remember the double-header in which a rookie named Grover Powell pitched a one-hitter in the opener. Usually the clubhouse was closed between games, but this time they opened it for the writers. A huge mob engulfed the young guy. Stengel got a pad and pencil from somewhere and stood in the rear, pretending to be one of the press. There was a lull in the questioning, and all of a sudden there was this croak from the back that was unmistakably Casey’s.

“Was you born in Poland?”

I became the Telly’s regular track and field writer. The indoor meets in the Garden were thrilling. There’s no other way to describe them. The bang, bang, bang of spikes on the boards, as they pounded around that 11-lap-to-the mile wooden track. The band. Especially the band. It was a Garden tradition, the band in its uniforms, blasting away with John Philip Sousa or Franz von Suppe, as the runners went around and around. Years later the famous character actor, Roscoe Lee Browne, who was just Roscoe Browne when he was running for the New York Pioneer Club, told me that the band was the thing he remembered about the meets in the Garden, how he had loved running with all that music.

The football Giants were New York’s darlings. Charlie Conerly was the Marlboro Man, draped over Broadway on a billboard. The huge image of Frank Gifford puffed away on his Lucky Strikes. Fans and players around the league resented the flood of publicity Giants players got, along with the endorsements, as well they should have, because at times the gushing was almost out of control—until the team came down to earth in 1964. The Titans were a curiosity, an AFL joke until they became the Joe Namath Jets. College basketball was big in the Garden, even the NIT, which is just a shadow now. I’d been going to the Garden for the games ever since high school, always ending the evening with a one-block walk to 49th and Broadway and Jack Amiel’s The Turf, the restaurant with the neon horses. Lindy’s cheesecake got the publicity, but real aficionados knew that no place could touch the Turf’s. I’ve never tasted any that could.

Once, I was having my usual postgame cheesecake in The Turf, and I saw a sign, “Why Not Take a Cheesecake Home?” Why not, indeed? I checked my pockets. Yes, I could afford it. It was cheap enough. So I did. It was all I could do to keep from tearing the box open on the subway home. When I arrived I went to the kitchen and knocked off a quick piece. Then another. Then I arranged a little cheesecake and milk picnic to take to bed. I got about halfway through it, and all systems shut down. I had overdosed. The thought of another bite was revolting. Pretty soon even the thought of it in the house was revolting. So at 2 a.m. I got it out of the refrigerator, removed it from the box, opened the living room window and let it fly, six floors down.

In the morning the street looked as if the Japanese had invaded and spread out their flag. It was the rising sun, a burst cheesecake.

To some of us Bobby Knight was always the wide-eyed young guy at the college basketball luncheons at Mamma Leone’s; somehow the ogre he was described as in his later years never rang true.

It seemed that writers for every sport had their own luncheon at Mamma Leone’s, even college football, which wasn’t a really big deal in the city, although West Point usually was good for some ink. There were seven dailies in New York, and if you added the Long Island Press and Newsday and all the metropolitan Jersey papers, you had a serious mob of writers in attendance. No, not Media, although an errant radio or TV guy night stray in. Writers—what they now call, “Print Media,” making a face.

At one of the basketball writers luncheons I sat next to a young guy who had just come off Ohio State’s NCAA championship team and was working as Tates Locke’s assistant at West Point. He was wide-eyed, in awe of everything, the big-name coaches from the past, the journalists, each with his own set of credentials. It was Bobby Knight. Every now and then he’d ask me, is that Clair Bee over there? That can’t be Nat Holman, can it?”

I asked him if he’d like to meet Clair Bee. The legendary LIU coach always attended as part of the NIT selection committee or something.

“I’d really be thankful,” Knight said. He was only an assistant, but he became a regular at those luncheons. People who knew him then developed an entirely different relationship with him through the years. It’s hard to explain. To some of us he was always the wide-eyed young guy at the luncheons; somehow the ogre he was described as in his later years never rang true.

In 1973 I covered the NCAA Final Four tournament in St. Louis. Bobby’s Indiana team had been eliminated, and he was doing analytical pieces for the New York Times. We were at a big table in the press room, having lunch, one day, and Bobby said, “Hey, you were at the Olympics in Munich. What happened over there?”

“One big problem,” I said, “was that Hank Iba was drunk all the time.”

Iba, an idol of Knight’s, had been the Olympic coach. No sooner had I said that than his eyes started blazing.

“Goddammit!” he yelled slamming the table with his fist and making the plates and silverware jump. “Those are the kind of rumors you guys keep spreading around, the kind of rumors that ...” and so forth. I let him finish.

“Come on, Bobby. Ask Johnny Bach. Ask anybody.” Bach been Iba’s assistant in Munich.

“Yeah,” Bobby said, settling down and poking at his food. “I heard the same thing myself.”

I always got a kick out of that characteristic in coaches, because I used to do it myself. The self-induced burst of anger, almost uncontrollable at times. Bears coach Mike Ditka was a pro at it. In 1989 I covered the opening game, Bengals at Bears. Chicago won, but Cincinnati ran for a lot of yards, most of them against rookie defensive end Trace Armstrong. He became a fine player, but this was his first game, and he struggled. Ditka’s press conference always was in a kind of tent or bubble with a silver-metallic color. For some reason this seemed to infuriate him, because more than once I’ve seen him rip out the microphones and stalk out of the place. And that’s exactly the response that this day’s line of questioning drew from him.

“You’re trying to destroy a terrific young player, and I won’t let you!” he hollered and stormed out. I followed him, into the locker room and through it and into the coaches room. He sat down on a bench and started whipping the laces out of his shoes.

“You’ve got a problem there,” I said softly.

“Yeah, I know, I know,” he said, all anger completely gone. “How good was the guy he was playing against? Please tell me he was good.”

“Blados? One of those smart fat guys who can embarrass a rookie.”

“Well, at least he was good,” Mike said.

Nowadays I’d probably have a couple of security guys on my neck if I tried to walk into the coaches room without a letter from Lombardi’s ghost, but it was a friendlier era then. And even friendlier in the ’60s, when I felt myself really growing into the business, when I could, without getting all fluttery, crank out a deadline piece if I had to, heeding the immortal words of Til Ferdenzi of the Journal-American: “It ain’t great, but it’s done.”

Oh, I was riding high back there in 1966, a young sportswriter on the rise. And then came the merger of the Telly, official name the New York World-Telegram & Sun, with the Journal-American and the Herald Tribune. What had been at one time seven functioning dailies, merged into three, became merged into one. There was a brief strike over who would lose their jobs. I walked the picket line, carrying a sign that said “Uphold Seniority.” Seniority was upheld, and I was out of work. Six years weren’t quite enough. Which was fair, I’ll never complain about that, certainly a lot more fair than some boss’s nephew getting a spot that should go to a veteran reporter. But I was still out of work, married one year, living in New Jersey, bills to pay, all the trappings of suburbia, and no job.

Losing my job was the best thing that could have happened to me. I was turning into a punk, with an ego to match. This experience squashed it flat.

I repeated a litany to myself. “This is the lowpoint. It’s not gonna get any lower. This is the lowpoint, it’s not gonna get any lower.” I was back in my ’57 VW, checking the offices, cold, on the Coast. Everything had rolled away, the six years, all that hotshot stuff I was so proud of. But what had I done, really? A few years of schoolboys, some features, some baseball pieces, and of course, those stupid Frothy Facts columns. Did I want to do something else in life? No, nothing else.

When I got home I did something I’d never done, that cliché soap opera routine in which the guy comes in from work and immediately rushes to pour himself a drink, a metaphor for despair, for failure. My metaphor was Jack Daniels, a stiff one, easy on the ice. Looking back on it, I can’t relive the emotion I went through, but I get a feeling that it was the best thing that could have happened to me. I was turning into a punk, with an ego to match. This experience squashed it flat. I don’t recommend it to anyone with suicidal tendencies, but everyone with a high opinion of himself or herself should undergo something similar at sometime in his or her life. Yes, easy philosophy now, with the fire roaring and the chestnuts roasting and mellowness on all sides.

Finally I got a call from the Post’s sports editor, Ike Gellis. He said he’d give me a two-week trial. He was giving the same deal to Larry Fox, the Telly’s AFL writer. Winner take all. It was kind of a brutal arrangement, but let’s face it, part of being a sportswriter is writing under pressure, is it not? And this was the ultimate pressure.

It was baseball season, and I remember doing a piece about Whitey Herzog, the Mets’ third base coach, and to this day I still raise a glass (when I think about it) to Jim Maloney, the fire-balling righthander for the Reds who filled my notebook with snappers and one-liners and gave me a story in which I just had to quote him correctly and it would take care of itself. I think that’s what put me over the top and got me the job. I didn’t feel comfortable about Foxie getting the short end, but he came out OK, eventually becoming the Jets beat man for the Daily News and later their sports editor.

I didn’t realize it at the time, but a piece that wasn’t deadly serious but relied more on zingy quotes was right up the Post’s alley. It was known in those days as a “writer’s paper.” When I joined the Post in 1966, Leonard Shecter, who would go on to write Ball Four with Jim Bouton, was still appearing regularly. Larry Merchant had come in from Philly, Vic Ziegel was a young writer whose screwball angles were greatly encouraged, the zanier the better. Nine years later the Post would give life to a brash 23-year old and put him on the Knicks beat. Mike Lupica, who now writes one of the country’s best-known columns, for the Daily News, plus front-of-the-paper political columns, plus novels. The Post was a fun place.

I started writing the Post’s wine column. Consumers liked it. The wine fraternity, the Purple Panties set, hoisted their skirts and hollered eeek.

One of the best features of the paper was a column called Working Press, which allowed any writer on the staff to write an actual column, complete with picture. Opinions were encouraged. This was mostly for the beat men, and I took over for Al Buck on the Jets late in the ’66 season, but younger writers could get a shot, if they lobbied hard enough. So very early in the game you had the freedom to take a piece wherever you wanted. It created a habit of angling your stuff that stayed with you forever. And also got you in trouble.

After a few years I began writing the Post’s wine column. I’d been a wine buff for many years, and I finally convinced them that I could write better stuff than those run-of-the-mill puff pieces they were printing. I took shots, I had fun, I went to a lot of tastings. Consumers liked it. The wine fraternity, the Purple Panties set, hoisted their skirts and hollered eeeek. After a few years the ad manager, a guy named Brody, told me that he was having a tough time selling wine ads, and I was the reason why, and Mrs. Schiff, Dorothy, Dolly, Schiff, the owner, preferred me to do a “support column.”

A what? Says which? A column supporting advertisers and potential advertisers, he explained.

“Oh, plugs?” I said. “I don’t do plugs.”

“Exactly,” he said, “which is why a support column from you would be so valuable.”

Typical bean-counter’s illogic. I mumbled something like, “Support this,” in my smirking, wise-assed way, and next week my column was not in the paper, replaced by the efforts of a PR man for a distributor. I shrugged it off, after the usual hand-wringing, but a journalistic publication called More did a whole double-truck centerfold on the incident, illustrating it with a cartoon showing Mrs. Schiff, instead of a cork, popping out of a wine bottle.

At the Post we were always fond of tweaking the New York Times, the way they’d sit back and wait for stories to come to them, instead of joining the herd and chasing them, along with the rest of us. I had my own experience years later when the editor of the Sunday Book Review section called me with a request to review a book for them, a football book, naturally.

It was a pleasant enough read. I mean, old-timers always have stories to tell, and they’re usually pretty generous about sharing their experiences. But then, uh oh, something seemed familiar. It was a passage from my own book, A Thinking Man’s Guide to Football. Then I found another one, both uncredited, lifted, in other words. This was just too ironic. I mentioned it in my review.

“What a bad break, lifting from a guy who happens to be reviewing your book. Tough luck. Just ain’t your day, kid.”

I sent in my review and got a call from the editor of the section.

“Did this really happen?” he asked. Yes, it really happened. “Well, your review is kind of rough.” I told him I was sorry. And then he used a phrase that I’ve made part of my vocabulary ever since; my wife, Linda, even has adapted it to hers:

“Can you bland it down a little?”

I told him, no, I didn’t think I could bland it down.

Well, the review never ran. They sent me a $50 kill fee. And never asked me to do another piece for them.

* * *

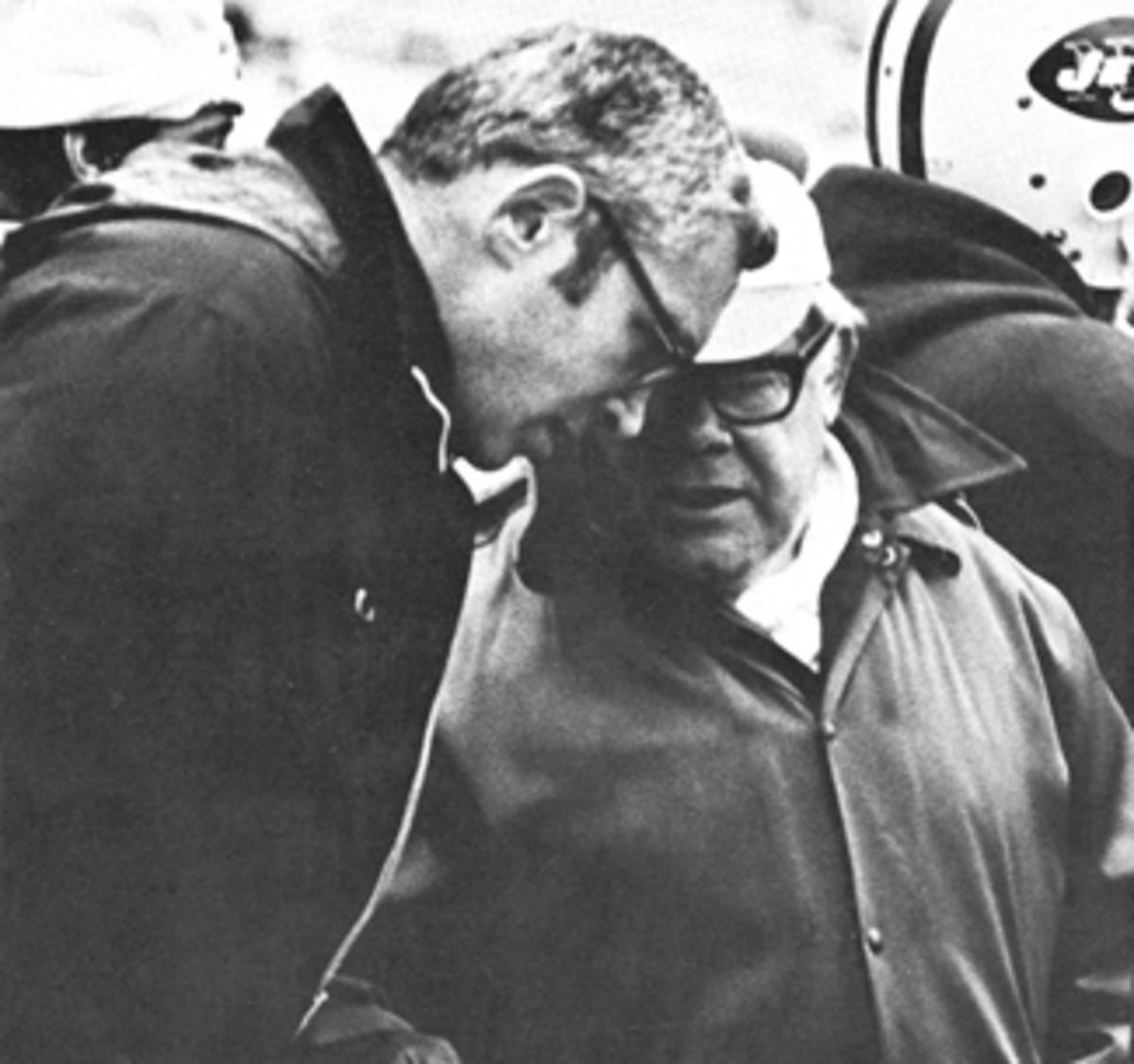

I spent 11 years on the Jets beat, 1966 through ’76. I had my ups and downs, usually relative to how the team was doing. I won’t give it the typical old boy’s lament about how different things were then, but gosh, I don’t see how they can cover the beat now, with all these restrictions. Half the head coaches in the league put their assistants off limits to the press, even though they’d been assistants themselves, and the publicity they’d received had helped them get their job. “One voice” is the mantra. Bill Belichick, for instance, is known as Coach One Voice. In the old days that would have been unheard of. Assistants actually wanted to talk to you. I think they still do, but won’t admit it.

Competition was pretty rough among the beat guys, especially on the three morning papers, Foxie on the News, myself, and Dave Anderson on the Times. You won one, you lost one, you got whipped on a story, you hit one of your pipelines and got your scoop. But at least the three of us didn’t pursue the exact same angle every day, as the papers do now. I can’t say I envy them. Everything is done on most clubs to keep the writers from getting a player alone. It’s always a mini-press conference. Access is strictly limited. Some clubs have a rule that the press can’t contact a player after hours, can’t call him on the phone, for instance. We used to live by the phone. Teams withhold information from the beat guys so they can release it on their own website, which is a source of revenue. And I’ve never seen so many bylined stories with attribution attached to some website or TV or radio show. I wince every time I see that.

Most of this came in under the stewardship of Commissioner Paul Tagliabue, and he never made a move toward improving the conditions for the writers. Yeah, I’ll vote for him in the Hall of Fame balloting, sure I will.

There, I’ve gotten it out of my system, the whining about how it ain’t like it used to be. I won’t dwell on it anymore. Maybe.

I begged Ike to let me cover Super Bowl I after the 1966 season. Nope, one man would be going, and it would be Al Buck. I just knew the Chiefs would beat the Packers and I wanted to be there to see it. Sorry. Never was I so psyched for a game. I had charts, and more charts within the charts. I had an entire table filled with them, getting ready for the telecast. A few hours before the game, the daytime desk editor, Sid Friedlander, called to tell me they needed me to cover the Warriors-Celtics in Boston. To this day I can’t tell you what I said. It was incoherent babble, stream of consciousness, the first thing that came into my head.

“Geez my father-in-law’s got to go to the hospital and there’s nobody here and my wife’s away and they’re calling now and he just fell down again I can’t start the car...”

“All right, all right already, we’ll get somebody else, geez...” I’ve been at every Super Bowl since.

Paul Sann, the editor in chief of the Post, was a strange guy. He ran the paper for 30 years and gave many important writers their start. He was about average height, wiry, with an iron-gray crew cut and deep-set eyes that always seemed to have pouches underneath, as if he hadn’t been getting much sleep. Maybe he hadn’t. He liked to wear turtlenecks, black usually, sometimes gray. I started affecting that look myself, the crew cut and the black turtleneck. I still do.

He could freeze you with a look. He scared a lot of people, and if they weren’t tough enough to take it, well that was too bad. But he loved sports, he loved coming into our little playpen and schmoozing with us. Red Auerbach was his big buddy. We were his toys. It was always a rough kind of give and take when he paid us a visit. He’d do an occasional book himself. In 1970 he wrote Kill the Dutchman, the Story of Dutch Schultz, and gave me a copy. I read it the same night because I knew he was going to ask me what I thought of it. Sure enough, next day he asked me.

I told him I got so excited reading it that I punched Artie Greenspan in the belly. Artie was an overweight cityside desk editor.

“Like this?” Sann said, letting me have one in the gut.

He cared very deeply about the quality of the writing in the paper. He liked hard reporting and writing to the point, without a lot of fluff, but he could put up with genuine emotion, too, if it wasn’t forced. One day, after I’d written something I thought was particularly clever, Sann came up to me and said, “Be careful, you’re getting a case of the cutes.”

We didn’t make much money on the Post. One year I got a tentative offer from the News. I didn’t think it was really serious, but the rumor made the rounds, and Sann picked up on it.

“The only way you’re leaving this place,” he said, “is with two broken legs.”

Red Smith, the Pulitzer Prize-winning columnist for the Times, was a terrific person to cover an event alongside, funny, compassionate, sometimes even shocking in his bluntness. At the Foreman-Frazier fight in the Nassau Coliseum on Long Island, there were a few students from the local college paper at ringside. One of them was working on what I thought was a remarkably sophisticated angle, asking different writers what they thought of Dick Young. Dick was the era’s enfant terrible of sportswriting. You crossed him at your own risk, because he never forgot and seldom forgave and one morning you might look at the News and find yourself skewered in his column,

It happened to me after a meeting of the fledgling Pro Football Writers Association. The NFL and AFL had told us that henceforth writers would not be permitted into the locker room on game day, before the contest began, as they were in baseball. Dick was furious. “Give them one concession,” he said, and they’ll keep taking stuff away from you until you have very little left.”

I argued that I thought the mandate was a fair one because football wasn’t like baseball, an everyday happening. Players had to get themselves ready all week, and it wouldn’t be fair to break their concentration before the game. In retrospect, Dick was right in his overall concept. Fight them at every barricade! Anyway, he turned on me with surprising venom.

“The trouble with you,” he said, “is that you forget which side you’re on. You think you’re still going out there and playing the game.”

It didn’t end there. I was subjected to a constant sniping in print, some days rougher than others. I made a noise like an oyster. He finally granted me a reprieve when we were seated next to each other at a Jets-Oilers game in Shea, and the first time Houston was going into the wind, I said, “Watch this. They’ll run the ball because Stabler doesn’t want to throw into this wind, and the first time he does they’ll pick him off.” Lord a’mercy, that’s just what happened. Maybe the best call I’ve ever made at a game.

Dick harrumphed a bit and finally said, “You really know what’s going on, don’t you?” And he gave me a nice little pop in next day’s notes column, and from then on I was off the hook. But when that college kid approached me for my opinion, I went into a tap dance.

“Very hard working, you certainly know where he stands at all times,” blab blah blah. Vic Ziegel, sitting next to me, gave him a similar response. We looked at each other. Yeah, right, like we’re going to take a shot at the guy in print. The next person the student approached was Red Smith, hat tilted back, a cigarette in his mouth, trying to get an early start on his column. The young man introduced himself and asked the question. Red didn’t even look up. He kept on typing.

“Dick Young?” he said. “Dick Young? He’s off his freakin’ trolley.”

* * *

In 1977 Dolly sold the Post to Rupert Murdoch. I had heard that he was a notorious union-buster, also the king of schlock journalism, but I didn’t know much more. Paul Sann and I discussed the arrival of Murdoch and his Australians.

“I think we’ll be all right with them,” he said. “I like what they say.”

“Talk’s cheap,” I said, trying to out-Sann Sann.

“Yeah, I know, but I think they’ll be OK, just watch.” I watched. He was gone in less than a month, despite Murdoch’s commitment to keep him on.

A piece I did on the Jets’ black-white relations all of a sudden bore the shrieking and totally twisted head: RACIAL STRIFE RUINS JETS.

We got our first real taste of Murdoch journalism in January 1977. A man named Gary Gilmore had been found guilty of murder in Utah, and he said he wanted to be executed. Utah obliged. We sent a cityside reporter named Barry Cunningham out to cover his death by firing squad, the last time that exotic ritual ever was used in the United States. Barry’s final advance described the anti-death penalty vigils that had been set up around the prison, the lighting of candles, the singing of hymns. In his second-to-last paragraph of the early edition piece, a deputy who had probably seen too many prison movies of the 1930s was quoted as saying, “We’d better bring more law enforcement in here. You can never tell what’s going to happen.”

Murdoch’s dayside editors lifted the paragraph to the top and made it the lead. The headline read: EXPECT THOUSANDS TO STORM GILMORE JAIL.

I was in the office when Barry came in to look at his clips. I positioned myself well, so I could have a good look at his face when he saw his advance. He came to it and his knees buckled. He issued a little grunt, “Ohhhh,” as if he’d been punched in the stomach.

At the time I considered it kind of droll, almost comic in a way, until it happened to me. A survey piece I did on the Jets’ black-white relations through the years all of a sudden bore the shrieking and totally twisted head: RACIAL STRIFE RUINS JETS, which caused their coach, Walt Michaels, who’d been my friend for many years, to stop talking to me. Then it wasn’t so droll anymore.

I was in for another big surprise, though. In April I was named lead sports columnist. Is this really what I wanted? Yes, I’d wanted it my whole career. Would Murdoch’s Australians have a free hand with my copy, with the column heads? No, said the new sports editor, replacing Ike Gellis, who had been swept aside by the same wave that sank Paul Sann. They certainly would not. So I became the lead sports columnist for the Post.

There were some good moments. The minute I got my invitation, along with other city columnists, to a preview of Rocky II, followed by a luncheon press conference with Sylvester Stallone and Carl Weathers at Gallagher’s, I had half the column written in my mind. First I’d set the scene—the press conference, everybody firing questions at Stallone, then all of a sudden my hand goes up and I say, “I have a question for Carl Weathers.” Ah, something different.

The question would be: “Was there a contract out on Roy Kirksey?” Blank looks all around. Weathers out of his seat in a rage. What the hell ... ?

And, to my great joy, that’s about the way it worked out. What made it better was that I heard Stallone turn to the guy next to him and say, “What is that guy, nuts?” And Weathers didn’t get mad. He just looked a little deflated. “Damn, man, you ask that after all these years ... I told you guys that night ... I was just trying to make the team.”

“Gerald Irons said there was a contract on him,” I said.

“Gerald Irons didn’t know dick.”

And the buzz among the folks in Gallagher’s grew louder, and the studio PR man didn’t like this private conversation one little bit, and I was about as happy as I’d ever been in my journalistic career.

Kirksey had been a 6'1", 265-pound guard from Maryland Eastern Shore, the Jets’ eighth-round draft choice in 1971, personally scouted by Michaels, then the defensive coach. “The greatest sleeper I’ve ever seen,” he said. He’d been a fullback in college, and he could run.

The first exhibition game that season was against the Lions. Kirksey ran downfield under kickoffs, burst into the wedge like a wildman and splattered bodies. No one had ever seen anything like it. Second game was against the Raiders in the Coliseum. Oakland’s Don Highsmith was returning a second-quarter kickoff. The wedge broke down and Kirksey beat his man, No. 49, and was positioning himself to make the tackle when he was cut down from behind by No. 49, the man he’d beaten. No. 49, second-year linebacker out of San Diego State named Carl Weathers. The ligaments in Kirksey’s ankle were torn.

Outside the Jets’ locker, Raiders linebacker Gerald Irons, who’d known Kirskey in college, told him, “There was a bounty on you, man. Al said we had to do something to slow you down.”

Kirksey dragged through a few more seasons, but he never regained the punch he’d had in his first game. When I talked to him, about a week before the luncheon, he was working in a teenage recreation center in his hometown, Taylors, S.C., blowing up basketballs for $183 a week. Weathers, of course, had made his reputation in Hollywood through his role as the champ, Apollo Creed, in the early Rocky films,

“Every time the weather changes and my ankle starts hurting,” Kirksey had told me, “I think about Carl Weathers.”

At one point in this period, a newspaper strike had been threatened. All of a sudden our sports department alcove was filled with a milling bunch of slack-jawed, pot-bellied lowlifes with Australian accents: Murdoch’s Aussie legion from the San Antonio Post, the first American paper he had acquired. It was hard to get work done with them around. The arrangement was that they would be observers, and we were supposed to “show them the ropes,” so they could fill in—scab it up in other words—when we went out on strike. “Journalistic scum,” we called them.

One morning I found one of these characters going through the mail in my box. I grabbed him by the shirt. “What the hell are you doing?” “Oh, ryte myte,” he said in that Aussie twang.

“I’ll freakin ryte myte you!” I said, but cooler heads pulled me away. No sense risking your job and all that. Just to show that their heart was in the right place, though, Murdoch’s homeboys ran up $10,000 in phone calls to Down Under. The lines had been left open, out of trust. I hate to admit this, as an enlightened member of the liberal elite, but it took me a long time until I could overcome my prejudice against anyone with that Australian accent.

And into this abyss, riding in like St. George with his lance, came the recruiter from Sports Illustrated. “We want you to be our pro football writer.”

* * *

I’d had some dealings with the magazine, beginning very early in my journalistic career when I’d tried to sell them a couple of freelance pieces. Sterling Lord, the famous literary agent, had given a seminar in magazine writing when I was at the Columbia J-School—actually magazine article selling, emphasizing that there was always money to be made, selling a piece to a major magazine. He left us with the strong request to “send me any ideas you might have.” Next day I sent him half a dozen, leading with an experience I had had as a student, a paid volunteer taking part in an early LSD experiment at the Neurological Institute. I even had a title: “Twelve Hours of Madness.”

Make that 13 hours, because the Sterling Lord Agency never responded, which I guess was part two of his seminar—how to deal with agents who don’t want to deal with you. The idea of turning short newspaper pieces into longer ones, for money, stayed with me, though, and the first outline I sent to Sports Illustrated was about a 10-year-old tennis phenom, a “can’t miss” child named Rosemary Casals, nicknamed Rosie. The response was a turndown.

“Often ‘Can’t miss’ stars do,” was the response, which I thought was very clumsily expressed. [Casals became one of the most prominent women’s tennis players of the ’60s and ’70s.]

I had seen SI writers when I was out on the beat, covering stories. Arrogant, snooty people for the most part, checking their watches and sighing in impatience as you tried to do a locker room interview.

Then I sent them an idea about La Sierra High School, in the Sacramento suburbs, which had a schoolwide fitness program that separated all the students into different fitness levels, identifiable by the color of the gym shorts they wore, creating a frantic atmosphere in which everyone worked out like a maniac. There was no response to this, but a month later Sports Illustrated sent its own staffer out to La Sierra and did a piece on the identical subject. Imagine that.

Strike three was when I was out of work between the World-Telegram and the Post and I applied to SI for a job. I actually got a pretty nice lunch out of it. I was escorted up to a management dining room called The Hemisphere Club by Jack Tibby, a senior editor, who asked for my honest opinion about the magazine. I told him what I’d liked and what I hadn’t like in the last few issues.

“You certainly are prepossessing,” he said. I had to look the word up when I got home. I didn’t get the job.

“Oh, Jack,” one of the editors told me years later, when I actually began to work there. “We called him our editor in charge of table manners. You didn’t drop any silverware, did you?”

And of course I had seen SI writers when I was out on the beat, covering stories. Arrogant, snooty people for the most part, checking their watches and sighing in impatience as you tried to do a locker room interview, because it was delaying their dinner plans for the athlete or athletes you were interviewing. But that was just it. SI was taking them out to dinner. You were scrambling through the backwaters down below. Yes, there was envy mixed in there.

And now this man was offering me a chance to be one of them. Well, uh, yeah. When do I start? It cost me my severance that had been building for 13 years, and my pension, but it was worth it. Off I went. August 1979.

I found out later that I had stepped into a sociological maelstrom. Tex Maule, an analyst, a “nuts and bolts guy,” as the magazine’s editors used to say, had been SI’s lead pro football writer for 19 years, taking over a couple of years after its birth in 1954. By the 1970s the magazine was ready to move, as football coaches say in that dreaded euphemism, “in another direction.” Style was called for, brilliance, sparkle. Nuts were out, and especially bolts.

The magazine had been split into factions, the editorial faction and the Jenkins loyalists, who I’m sure viewed me as nothing but a house ape, a nuts-and-bolts thug.

The new pro football writer was Dan Jenkins, whose brilliance had been established in his chronicles of college football and golf, but who admitted that “I frankly don’t like pro football.” Now he was the man, never really appreciated by SI’s managing editor, Gil Rogin, nor his football editor, Mark Mulvoy, but idolized by a whole coterie of young writers for his wit, his eloquence and, according to editor Steve Wulf, his ability to “overview a story like no one else could.”

But Rogin and Mulvoy both grew to feel that pro football had become America’s number one sport, a happening so serious that it needed more than wit and eloquence and even the stylish wrap-up, or overview. It needed, and I cringe as I mention this, because Mulvoy said it to me the day he offered me the job, “more nuts and bolts.” Oh God, how many times did I hear that? Jenkins switched to golf, I became the pro football writer.

I had become the centerpoint of a controversy of which I wasn’t even aware. I had no idea how Jenkins felt about me. I can only guess, and it couldn’t have been good. I knew him only slightly, just enough to say hello to. I hadn’t been one of the young writers who worshipped at the shrine. Hell, I was 46 when I joined SI. Too old to worship.

I got a strong taste of what I later came to understand as a pretty firm resentment in 1980 when I was on my way back from a feature assignment, and I just stopped over in Dallas to watch the Cowboys-Niners game, not as a job but recreationally. Dan had been pulled from golf that week to cover the contest. He looked surprised to see me in the press box, and not too friendly. What the hell is he doing here? I told him I was just there for a look-see and I’d pick up losing dressing room quotes for him, to help out, if he’d like. At the Post we used to do that all the time, and SI hadn’t sent anyone along with Dan to give him a hand. He looked at me closely to see if I was serious.

What he saw was a naïve face, devoid of irony, and just what I claimed to be, a guy trying to help out. He softened. We got along. That’s the last time I saw him. What was unknown to me was that the magazine had been split into factions, the editorial faction and the Jenkins loyalists, who I’m sure viewed me as nothing but a house ape for Mulvoy and Rogin, a nuts-and-bolts thug.

The irony there is that few people became as much a pain in the butt, as far as the editorial hierarchy was concerned, as me. I never got used to the editing, which had never been much of a concern at the Post, except for the occasions when Murdoch’s assassins were up and about. I got to dread the weakening connectives, “and,” “but,” “so,” inserted at random, the three- and four-syllable adverbial modifiers that took the guts right out of a statement... “supposedly,” “seemingly,” “presumably.”

“They keep them in a box and sprinkle them over your story like confetti,” George Plimpton, who once was an SI staffer, told me.

Especially feared were the explanatory parentheses. “Look, I’m not a Unitas or a Namath,” Terry Bradshaw said in one of my stories. In idiot lockstep came the (John) and (Joe), just to make sure everyone understood who he was talking about.

I hollered long and loud. “If I write about someone who went to Washington & Lee University,” I said, “do I put George and Robert E. in parens?”

Ken Rudeen, the senior editor, was in love with the word “moreover.” Four of of them in one of your pieces would tell you immediately who had edited it. Peter Carry, the assistant managing editor, loved “Heck.” To their ears, pure poetry. Thus, a fairly hardbitten Oakland piece, with the quote, “Hell, we’re the Raiders,” came out, “Heck, we’re the Raiders.” Oh heck, there’s that edit again.

Perhaps the most chilling statement in the 28 years I’ve worked there came from senior editor Jerry Kirschenbaum, when I was bitching, as usual, about some edit or other.

“You have to understand,” he said, “that our job is to put what you’ve written into institutional language.”

Even Jerry was stunned by that one, because later on he denied ever making the statement. Yes you did, Jerry, you did indeed. I heard it myself, and it’s why every hair I’ve got now is snow white.

I had a few brushes with fame during my stint as Sports Illustrated’s lead football writer. My name still is not well-received in Detroit. The reason is a stint on the Good Morning America show on the Wednesday following Media Day during 1982 Super Bowl week. Media Day had been brutally cold. We waited outside the Silverdome for the gates to open so we could go inside and attend the first event, the interviews with the 49er players. It was late, then it got really late. We were freezing. Jerry Izenberg of the Newark Star-Ledger gripped the fence.

“How about finding out when we can get in?” he asked one of the Detroit cops on the entrance. “You get your hands off that fence or you’ll get a stick across them,” he was told.

“I knew something was up when they finally let you guys in,” John Madden told me later in the week, “and I saw you march right up to the 50-yard line, stand there glaring and march right back. I said to my director, Sandy Grossman, ‘Watch, something bad’s gonna happen with him.’ ”

Next day I was on Good Morning America with Joe Falls, sports editor of the Detroit News. I ripped the idea of a Detroit Super Bowl, I ripped the league, the arrangements, everything. Charlie Gibson asked me how I’d compare the Detroit police to the KGB, since I’d been to the Moscow Olympics in 1980. I said, “Very similar except that the KGB guys were more gentlemanly.”

I knew something was up when one of the ABC technicians wanted to fight me as I was leaving the studio.

“I bet you’re one of those assholes from New York,” he said.

“No, I’m from Hamtramck, Michigan.”

“Like shit you are!”

“Like shit I’m not.”

And then they pulled us apart. In the cab back to the hotel, I said to Joe, “I think maybe I said something bad on the air.” He said, “I think maybe you did.”

The local papers took a shot. So did every radio talk show host who had ever written a high school editorial. One guy mentioned that he was sure I’d like to hear how Detroit people felt about my sentiments, so here is the name of Dr. Z’s hotel and the number of his room. So the crank calls started, practically round the clock.

A year later the league meetings were in Phoenix. Curt Sylvester of the Detroit Free Press came up to me and said, “Your name is still mentioned in Detroit. Give me a quote about Phoenix for my notes column?

“Too hot,” I said. “Wish I were back in Detroit.”

And wouldn’t you know that I got a letter from a Detroit reader? “First you bitched like hell about our city, now you’re bitching about Phoenix,” etc. Perfect.

“The player of the 1990s,” I said on the ESPN draft show, “will be so sophisticated that he’ll be able to pass any drug test they can come up with.” The switchboard lit up, and when they came out of the commercial I was off the set. And my ESPN career was over.

My second brush with notoriety came when I was doing the draft for ESPN. Some time in the late 1980s, I was on the anchor desk with Chris Berman and Joe Theismann and someone threw out the question: “What will the player of the 1990s be like?” Their answers were predicatable. Bigger, faster, stronger, and so forth. But oh no, I had to be different and give it something special.

“The player of the 1990s,” I said, “will be so sophisticated that he’ll be able to pass any drug test they can come up with.”

I expected to be asked why I said that, and I was going to mention that the players and the steroid labs were so much better funded than the NFL program was at that time that their masking agents would be too sophisticated to detect, unless the league allotted more money to it. See, nice and logical. Except that both of them gave it the shocked look: “Well, I’m not touching that one.” “I’m not, either.” And they went to commercial, and the switchboard lit up, and when they came out of the commercial I was off the set. And my ESPN career was over.

Number three was my foray into big-time telecasting, third man in the booth for NBC in 1990. First game I worked was Seattle-Kansas City with Charlie Jones and Sam Rutigliano. Sam was a novice, I was a novice, there was a lot of hollering and screeching going on, with poor Charlie trying to control the lunatics. Mike Weisman, the NBC sports director who had hired me, admitted it was “a mess.”

Next game was Denver-Pittsburgh with Bob Trumpy and Don Criqui. This time they fortified themselves by turning my mike off. I could only come in on command, in other words, speak when spoken to, and then they’d turn it on for my reply and shut it off again, Things went so smoothly in the first half that they opened up my mike for the second one. Uh oh. Their fatal mistake. On the first series, a Broncos tight end caught a long pass.

“He beat that strong safety like a drum,” Trumpy said.

“He didn’t beat anyone like a drum,” I said. “No one can hold his cover if the quarterback has that much time.”

“I say he beat him like a drum!”

“And I say he didn’t.”

Poor Don Criqui had his head in his hands. The technicians were breaking up and making chopping motions with imaginary hatchets, across their necks. Thus ended my career as third man in the booth.

“Your style is passé,” Mulvoy told me. I complemented him on his use of a French descriptive.

Worse was to follow. Three or four years later I was informed that Sports Illustrated was off the nuts-and-bolts kick, or maybe they were just tired of my nonstop whining about the edits, because I was dethroned as top gun. From now on I’d just be dancing in the chorus, another pretty face. “The Lord giveth, the Lord taketh away,” as Chuck Noll once told me when I asked him if he shoveled snow in his driveway in the winter.

“Your style is passé,” Mulvoy told me. I complemented him on his use of a French descriptive.

Fine and dandy. I could still pick my All-Pro team, still do my Super Bowl forecasting piece and my preseason handicapping. And then around 11 or 12 years ago the website came along, SI.com. I would have a regular column, which gradually grew to three pieces a week. Very light editing, and I’d have a look at the proposed changes before they were applied, and I could argue my case on each one, if I wanted to. I could take it in any direction I wanted, run off on tangents, bring my wife into it, write about wine. OK, those last few were my own ideas, but nobody argued.

Linda Bailey Zimmerman became The Flaming Redhead in print, her caustic and wry observations always serving to take down the arrogant blowhard that was my persona in print.

“From the ashes the phoenix rises,” a friend of mine commented. “You have carved out your own little empire.”

We’d like to hear your thoughts and memories of Dr. Z. Send them to talkback@themmqb.com.