When He Was Dr. Z

WEST CALDWELL, N.J. — “How’re you feeling, Paul?”

Everyone turns to Paul Zimmerman, who has been listening to the conversation quietly from his wheelchair. He grunts, curls his mouth into a mock snarl, lifts a clenched left fist and pretends to pound it against his chest. That’s the athlete in him, trying to show two old friends that he is still tough, still strong as ever.

His wife, Linda, interrupts. “He’s actually hurting like hell inside.”

Zimmerman’s face turns somber, and he stares into space as she goes into detail about his condition. Even if he wanted to, Zimmerman can’t explain how he feels. Ever since suffering a series of strokes in 2008, he has been robbed of many basic human functions. He can’t read. He can’t write. He can’t talk, except a few words. The entire right side of his body feels weak. A back injury from his football days sends shooting pain down his legs. He needs a wheelchair to get around and requires constant supervision and help with simple tasks like bathing himself. Last summer he fell while Linda transferred him from the shower to his chair, which led her to believe she could no longer care for him by herself. She moved him out of a home he had lived in for 50 years, 10 miles east to an assisted living facility.

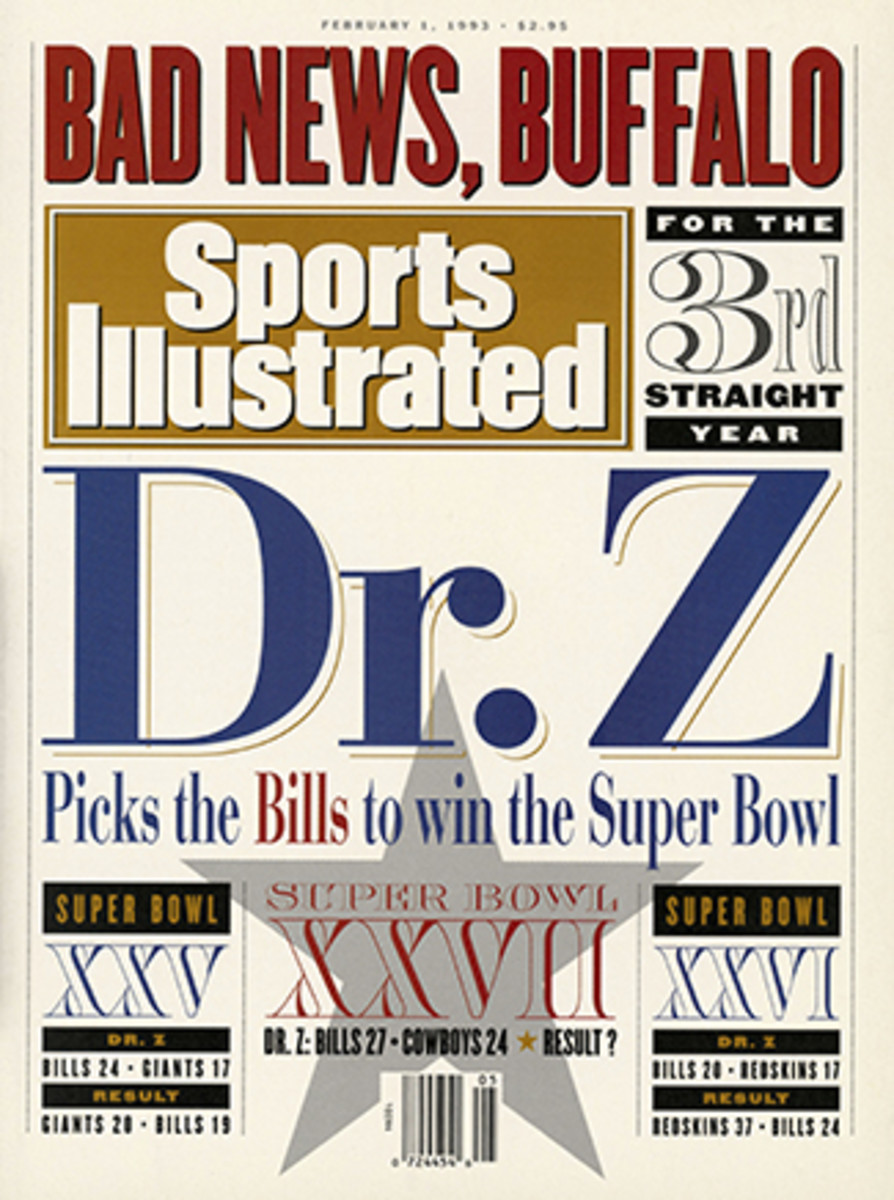

This was strange, having someone else communicate for him. He worked for about five decades, including nearly 30 years at Sports Illustrated, and rose to fame as Dr. Z, one of the most recognizable bylines in football history. Beyond sports, he had enjoyed debating politics, making crude jokes, giving wine recommendations, and traveling the world using the five different languages he spoke. Now, he is muted.

Zimmerman can only express himself by saying “Yeah” or “No,” giving a thumbs up or thumbs down with his left hand, or through animated body language, waving his arms and contorting his face. When he tries to speak in complete sentences, every word comes out as “when, when, when…” repeated over and over. Among friends, he still gets his feelings across with a look, a grunt, or an eye roll. Linda knows him well enough that she can translate, too.

The only writing Zimmerman does now is when he marks an “X” or an “O” on the chart detailing his daily exercise routine. But there is one last piece he wants help finishing—the memoir he was working on before he became debilitated. It is a collection of stories and anecdotes from his career, featuring characters ranging from Bill Walsh to O.J. Simpson, with his usual humor sprinkled in. These are the memories he clings to. This, too, is perhaps the best way to know what he’s thinking now that he can no longer speak for himself.

In one chapter, he describes being very aware of getting older, his changing appearance, and how his perception of the world changed as he aged. He sounds aware of his own mortality, afraid of what’s to come.

“The eyes, thank God, have not gone vacant yet,” he wrote. “ …[M]y father, when he was nearing 80, you would occasionally see a reflected kind of light in his eyes, but very little from within. Unless you got him annoyed, or angry. Then the stokers would report for their shift and you’d see the start of a small flame. I would deliberately provoke him at times, just to see those flickers, unable to face the fact that there really wasn’t much left.

“No, I haven’t gone blank yet. But the other one is tougher, that startled look you see in old people when someone comes into the room, without warning, or somehow their perspective has been even slightly altered. Their eyes flash, almost in pure terror, and then the look subsides. That’s the one that scares me. I say to my red-headed wife, ‘You’ll tell me, won’t you, if my eyes get crazy and scared for no reason?’ Yes, I’ll tell you, she says, but I wonder. The thought terrifies me, the dimming of the flame, the eyes that gradually pick up that glaze.”

His eyes haven’t glazed yet. And the one surefire way to see that small flame again is to talk about football and the glory days. Then he’ll nearly leap out of his chair.

* * *

The first time Zimmerman stepped foot in an NFL locker room was after the 1960 NFL Championship game between the Eagles and the Packers. He was 28, working for a New York newspaper. His assignment was to go to the losing team’s locker room (the Packers’) and gather quotes for the paper’s regular football writer. All he had to do was follow the scrum of reporters circling around the big names: Lombardi, Starr, Hornung.

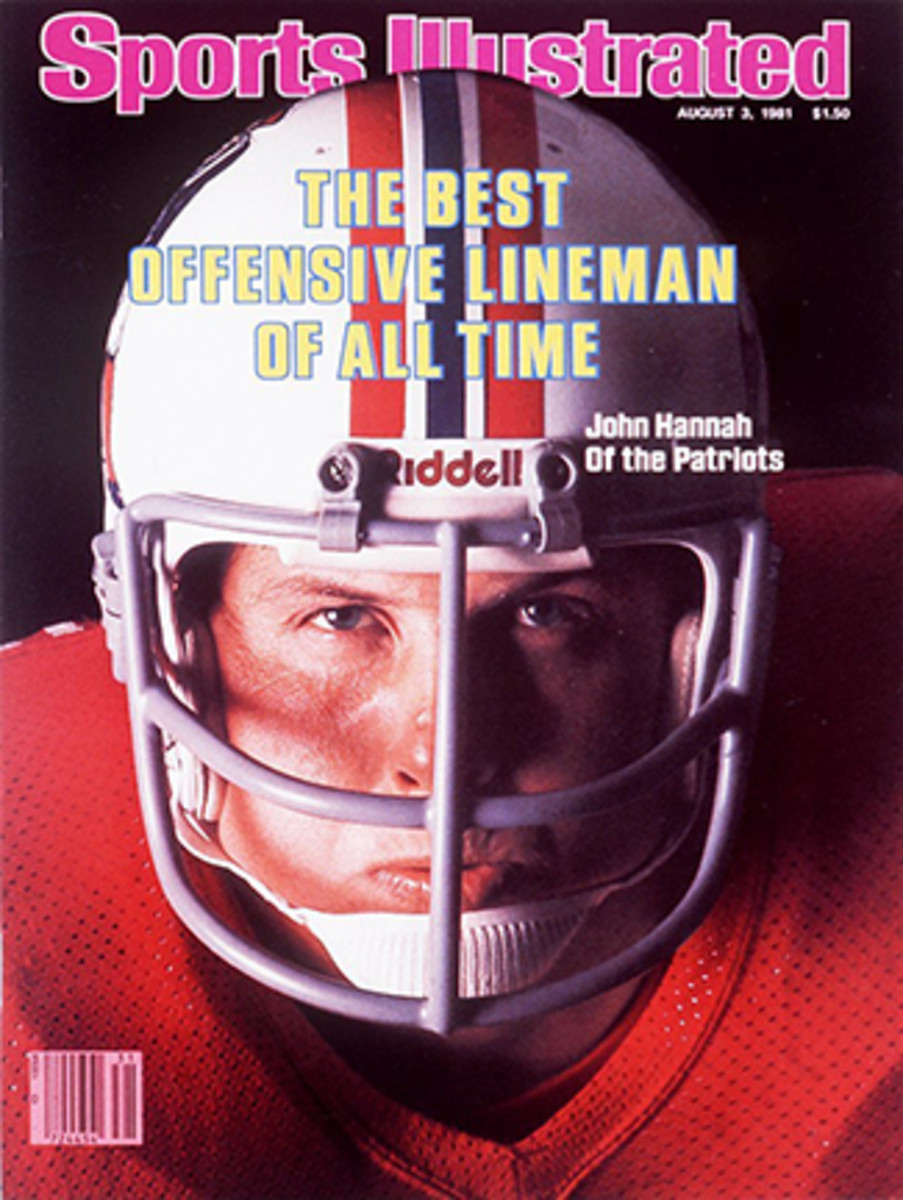

But he could not stop thinking about how the Packers’ offensive line had dominated the Eagles, the legendary Chuck Bednarik in particular, and how smoothly they had called their audibles. Zimmerman was playing for a semi-pro football team then, and he and his line mates were having issues calling audibles themselves. He found two linemen, Fuzzy Thurston and Jim Ringo, and, for 10 minutes, he was lost in conversation about the finer points of offensive line play, particularly how the Packers made their calls in specific situations.

When he finally looked up, the locker room had mostly cleared out.

No sportswriter ever knew the game of football as well as Dr. Z, and that was mostly because he had played it at a relatively high level. He was an offensive lineman at Stanford for a few years, spent a couple seasons in semi-pro ball, and even coached the equivalent of the junior varsity team while he studied journalism at Columbia. Seeing the game as a coach or player gave him a unique perspective and style, as he transformed from Paul Zimmerman into Dr. Z, football savant and all-knowing prognosticator.

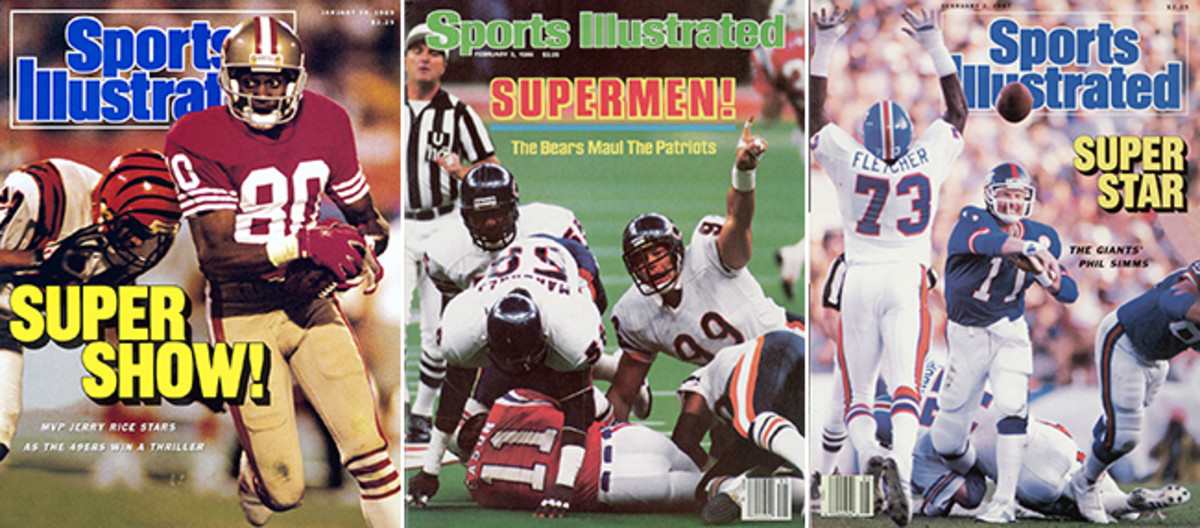

Dr. Z watched the game from the press box as a coach might: He walked in looking disheveled, carrying an oversize gym bag stuffed with papers. He snorted when he talked and hardly said a word because he was so intensely focused on the game. If you dared interrupt him, it had better be to discuss strategy. He kept a white towel slung over his shoulder to because he was prone to perspire while he feverishly scribbled notes.

And Dr. Z was scribbling the whole game, because he charted every single play using an elaborate color-coded system. His charts looked something like “hieroglyphics or some ancient scroll,” that only he could decode, says Rick Telander, who worked with him at SI. The charts went way beyond basic information. If a quarterback threw an interception, for example, he noted the type of pass, whether the ball was catchable, where the fault lay.

For precision’s sake, Dr. Z also clocked the hang time on punts and, for his own pleasure, the length of the national anthem. At one point in time, when a stat was announced in the Jets press box, everyone waited another 30 seconds for Dr. Z to confirm or correct it.

His encyclopedic knowledge helped him relate to coaches, executives, and players. He spoke their language, and they treated him like a peer. “Players reacted to him differently than other sportswriters,” says Linda Marsch, another SI writer. “They knew he knew what he was talking about. Really knew. They respected him.”

When there wasn’t a game, Dr. Z often bought drinks for players, took them to dinner or had them diagram plays on film. He called coaches and talked strategy. Agents used his All-Star teams in contract negotiations. Working on his annual draft column, Dr. Z would call general managers and “tell me who we were going to pick,” says Ron Wolf, the former Packers’ general manager. “I’m sure maybe once or twice he would’ve been right.”

His stories were a gold mine of information and analysis, the result of constantly thinking about football. “You know, there’s a thin line between working hard and obsession,” Dr. Z once told Telander. “And I think I’ve crossed the line.”

In the dying days of Dr. Z's first marriage, his wife tried talking to him during a Cowboys-Redskins Monday Night Football game, he vividly recalled in his as-of-now-unpublished memoir.

“We have to talk about this,” she said.

He had his charts all set up, his eyes glued to the TV.

“Can’t we talk about it at halftime,” he asked.

She practically shrieked: “Now! We’ve got to talk about it now!”

Dr. Z quickly jotted down the number of the player making a tackle, got up, and put his arm around her, trying to calm the situation. “It’s not that bad,” he said, watching the next play out of the corner of his eye, carefully. Then: a time out. Thank God, he thought.

The next day they decided their marriage was over.

“Did you miss a single play?” his wife asked.

No, he had not.

“Amazing,” she said. “Simply amazing.”

• WELCOME TO DR. Z WEEK: Peter King kicks off the week-long tribute to the football writing giant.

* * *

During the pre-internet era, working as a fact-checker at Sports Illustrated was a particularly intensive job. It involved checking archives, reviewing clips, scanning books, and calling the writer to go through a series of questions. If you were the poor soul assigned a story written by Dr. Z, you would have to psyche yourself up before making that call. Dr. Z would huff and puff and point out exactly why these were idiotic questions. He made the fact-checker feel as if they were wasting his time. “He took it as an affront that you would question anything he said about the NFL,” says John Walters, one of those fact-checkers.

“It was an intellectual beating,” Walters adds. “You needed a shower after you got done talking with Dr. Z. It was sort of like: ‘I just went three rounds with Joe Frazier; cut me, Mick, I’m done.’”

SI editors who encountered Dr. Z have similar stories. As Dr. Z became SI’s lead NFL writer and then one of the most prominent football writers ever, he developed a reputation around the office for being a malcontent. He argued with editors. He demeaned junior colleagues. He filed lavish expense reports. Some viewed it as the quirks of a mad genius. Others didn’t see the humor; they found him to be angry and mean.

One famous story is still re-told at SI: Once, Dr. Z arrived at the office to find that a younger colleague had been using his desk while he was out. In a fit of rage, Dr. Z smashed a keyboard on the ground. When he saw that colleague days later, he glared at him.

Dr. Z usually directed his anger at editors who dared touch his copy. He didn’t figure himself to be a wordsmith, but changing a verb could send him into a wild tirade on the phone. “He was very particular about words,” says Andrew Perloff, one of his last editors at SI. “He really felt part of his audience was coaches, teams, and football insiders. And he didn’t want to write about a play and have someone edit it and change the football meaning.”

Dr. Z took it out on the editors in his expense reports. His second love was wine; he had written a wine column for several years, and he often used those dinners with players as his own personal tasting sessions, ordering the house’s most expensive bottles. Sometimes, editors wondered if Dr. Z had lied about entertaining sources—an old-school newspaper trick.

That was an important factor: Dr. Z was of another generation, a different time. He was among the last people at SI to give up his typewriter, which meant editors had to re-type his copy when it came in. At one point, due to a confluence of these factors, the top SI editors started phasing Dr. Z out, minimizing his role in the magazine’s football coverage.

“It’s like anyone who has their moment in time,” Telander says. “The future comes along and it’s disruptive, and it was very disruptive to him.”

Then Dr. Z met Linda in a Phoenix hotel exercise room during a league meeting. He mellowed out. The internet came along, and he experienced a career renaissance writing for SI.com, where he faced lighter editing and was mostly free to expound on football, wine, his wife, whatever he wanted. He filmed a humorous web series that featured football discussions with swimsuit model Brooklyn Decker. He showed more of his personality and built a loyal following that wrote to him religiously.

“I have to say, I was expecting him to be an old curmudgeon, and he couldn’t have been any more different than that,” Decker says. “He was such a softie. He was so funny.

“We had him in Monster masks. We dressed up for a Christmas episode, a Halloween episode. We were ridiculous together. It was like two little kids goofing around.”

Dr. Z was still going strong in 2008, at 76 years old. He was working on a memoir, charting games, still writing a few times a week, when, one Saturday in November, en route to pick up a newspaper, he swerved off the road and into a neighbor’s yard. An ambulance came and a crowd formed. He sounded disoriented, but he refused to go to the hospital. He had more games to watch the next day, too much work to do. No way.

Dr. Z never wrote about football again.

* * *

While covering the Jets for the New York Post in the 1960s and 70s, a headline on one of Dr. Z’s stories made Joe Namath angry—so angry that Namath vowed to never speak to him again. Dr. Z tried explaining that he didn’t write the headline, the writer never did, but Namath wasn’t hearing it. He refused one-on-one interviews with Dr. Z, and, drawing on his authority in the locker room, he told his teammates to do the same.

They didn’t talk for 24 years, not until Namath was long done playing and Dr. Z reached out to do an interview for an SI story; Namath had forgotten why he was ever mad. That day they swapped old stories and recalled old friends. It was the type of conversation Namath could only have with a certain number of people. The memories gave him goose bumps.

That was the last conversation they had. But Namath watched the Emmy-winning NFL Films piece about Dr. Z and his life after the strokes.

“The last thing he said in the film I often say myself,” Namath said on the phone last week. “I didn’t invent it and I don’t think Paul invented it, but it was a reminder: Time marches on, man. And that is so true. You don’t want to waste it, but…” His voice trailed off, and then he caught another train of thought. “I was tickled to see Paul’s growth over the years. To become the Dr. Z. To become the voice that he had become. To crossover and do the stuff he was doing with the print media and the TV media. Because I can remember, my mind’s eye has him locked in—shaking hands, him introducing himself to me. I remember that. I see that. His demeanor was humble, quiet, soft-spoken. Yeah. We got along up until I got upset over that headline.”

* * *

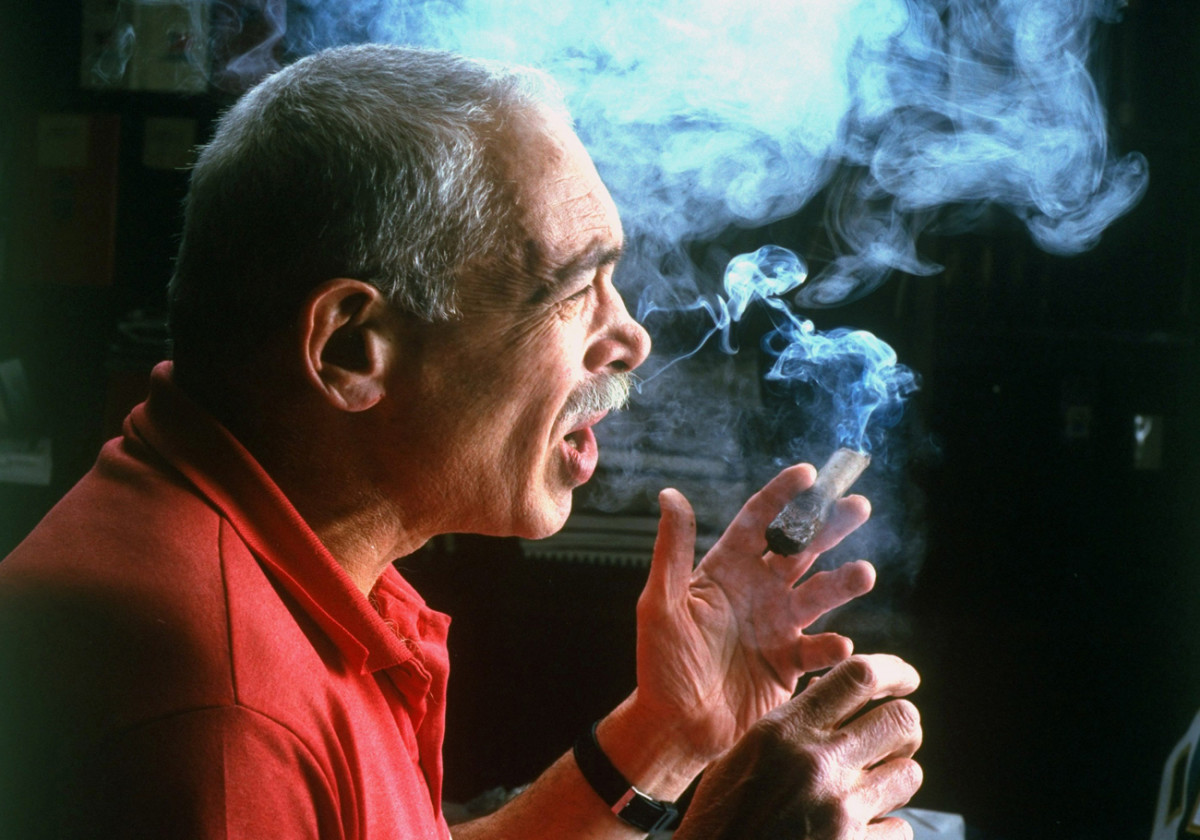

Hanging on the wall just behind the door of Room 1423 at Crane’s Mill Assisted Living Facility are photos chronicling Paul Zimmerman’s life. Paul as a young man with a chiseled chin. Paul with big cigar sticking out of his mouth. Paul with his rugby teammates. Paul charging downfield in full uniform.

Linda turns to him. “Do you miss it?”

Zimmerman arches his eyebrows and thinks for a moment.

“Yeah,” he says softly. “Yeah.”

“I think you’ve tried to lie to yourself,” Linda says, “and say it’s not what it was, but…”

“Yeah,” Zimmerman says once more, nodding quietly.