Where Have All the Deions Gone?

Welcome to Baseball Week. As training camp approaches and baseball takes a break for its mid-summer classic, The MMQB presents a week of stories on the crossover between hardball and football.

The logistics of it were so harrowing, none of the half-dozen newspaper reporters who wrote breathless tick-tock columns the next morning even attempted to witness the whole thing in person. They would borrow second-hand reporting from better-positioned outlets in their attempt to cover Deion Sanders doing the impossible—three games in two major professional sports over a 24-hour span.

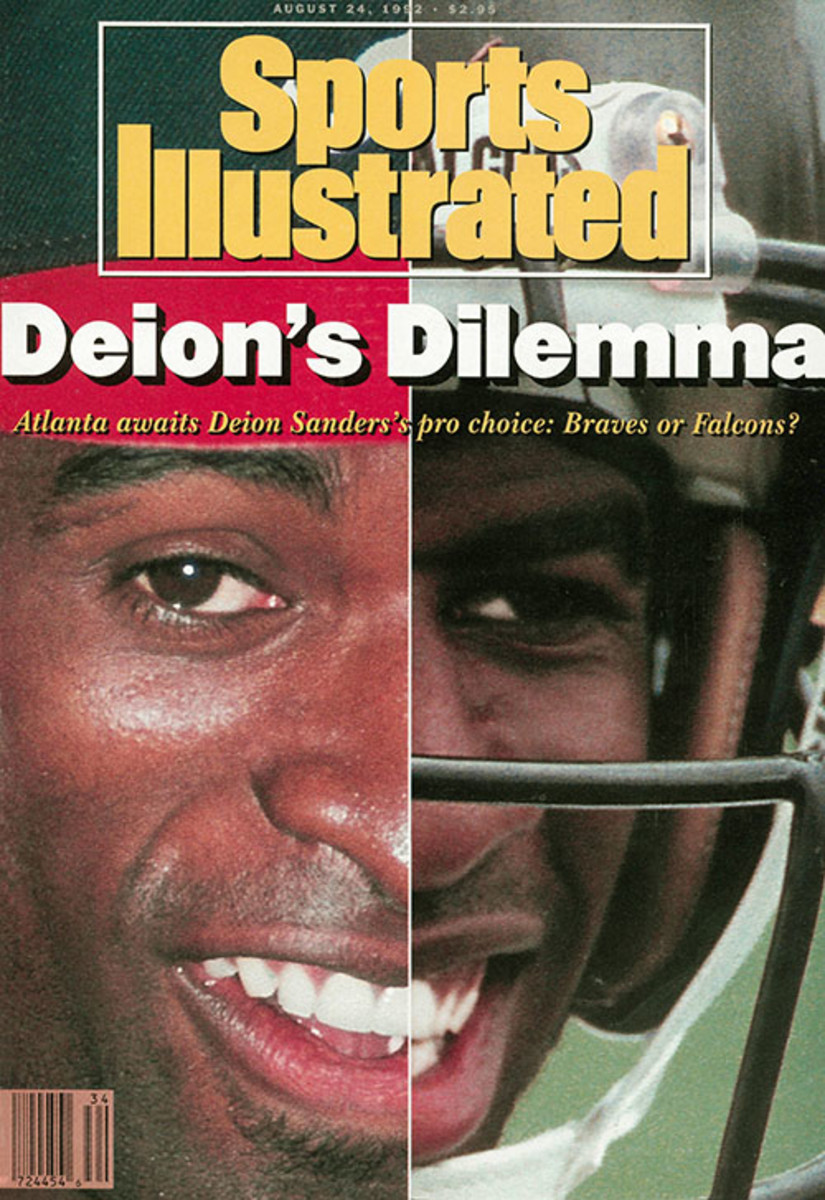

It’s a feat that hasn’t been sniffed since 1992, when a 25-year-old Sanders, bandana’d and bejeweled, was performing the early-fall juggling feat that would define the first half of his careers in Major League Baseball and the NFL. He became the last man to capture the nation’s imagination as the rarest breed of athlete: the two-sport star in his prime. Why hasn’t it been done, or even attempted, since? And under what perfect storm of circumstances could it happen again? The answers are with the men who saw it through unfiltered lenses that October.

* * *

When the Atlanta Falcons drafted Sanders fifth overall in 1989, it marked the third time he’d been drafted by a team in a major American pro sport; the Royals had picked him in the sixth round in 1985, when he was 17, and the Yankees took him in the 30th round four years later. After being released by the Yankees when he committed to training camp with the Falcons, he signed a free agent contract with the Braves in 1991. In 1992, the inevitable happened—the Braves reached the playoffs, and Sanders found himself spinning across the country in helicopters and chartered planes, between postseason baseball and a regular-season football game 1,200 miles apart.

A month earlier, Sanders had made his NFL season debut in the season’s second week; he had missed the opener because of the dual-sport arrangement. In the second quarter at Washington’s RFK Stadium, he introduced himself to new teammates. One of them was defensive back Louis Riddick, who later went on to a scouting career in Washington and Philadelphia and now works as an analyst for ESPN.

“He comes into the kick return huddle on the sideline, and he hasn’t been to one practice I can remember,” Riddick says. “And he goes, ‘I just need a little room. Y’all give me a little bit of room and I’m taking it to the house.’”

“I’m thinking, This guy hasn’t done s--- but he’s taking it to the house. O.K.”

Sanders fielded the kick at the one-yard line.

“I remember him going by me on the front line, and then he broke it to the right sideline,” says Riddick, who estimates that, of the 99 yards Sanders ran on that return, 40 of them were spent high-stepping. “That was the very first time I ever saw him do that signature dance that you see in the old highlights. You’re a part of it, on the field, but you’re also just watching it, and you realize he’s just different. That’s just God-given.”

After that, as the Braves soared through the NL West, finishing eight games ahead of the Cincinnati Reds with Sanders batting .304 and leading the league with 14 triples, nobody at Falcons HQ complained publicly if Primetime missed a few practices. If there was dismay in the locker room, it was whispered and never acted on.

“No one gave a crap,” Riddick says. “Because you knew that he could do stuff other people couldn’t. It’s not like he tried to get away with it. It was just, I’m good enough to do both, I’m trying to do something very few people have ever done. And you admired it. You were encouraged by it more than you hated on it.”

Jerry Glanville was in his third season of a four-year stint coaching the Falcons, and one year earlier had let Atlanta to its first playoff appearance in almost a decade: “I was very surprised by [players’ attitudes],” he says. “You’d think the team would be mad that he wasn’t at practice, but they were always thrilled with what he was doing for the Braves. I think everybody loved his spirit so much, and everybody knew he worked so hard.”

Strategically, Glanville says Sanders’ absence from practices didn’t have much effect on the gameplan, because the team would typically ask Sanders to either lock down the other team’s No. 1 receiver, or they’d rotate zones away from Sanders and leave him on an island. “Cat coverage,” as Glanville terms it.

“I’d say to him, You see that cat wearing 81—or 17 or whatever the best receiver had on that day. You see him? You’ve got that cat all day; I’ll see you when the game’s over. Great coaching.”

* * *

“Saturday night in Pittsburgh,” wrote Christine Brennan of the Washington Post on Oct. 12, 1992, “he played the final three innings in left field and struck out in one appearance at the plate in the Braves’ 6-4 victory over the Pirates. To the chagrin of Braves management and the delight of his Falcons teammates, he then boarded his chartered Canadair Challenger—at an estimated round-trip cost of $8,000—and flew to Miami to play another sport.”

Sanders would miss the team breakfast in Miami and turn up late for pre-game warmups. Glanville says he wasn’t sure if Sanders would even show up until he saw him dressing in the locker room after warmups.

“Deion is flying in a helicopter to the Dolphins game and he hadn’t practiced with us all week,” recalls Glanville. “I said, ‘Well you weren’t here in practice so I’m not starting you, and the whole team looked at me like, What? After the first play I said, ‘O.K., that’s enough punishment, go in.’”

By 4 p.m. on October 12, Sanders had held four-time Dolphins Pro Bowler Mark Duper to three catches for 27 yards in a 21-17 loss (Sanders added one catch of his own, for nine yards). Team medical staff administered a postgame IV, then, wrote Phil Hersch of the Chicago Tribune, “Sanders is the last Falcon to leave the locker room. He is dressed in an orange-and-black shirt with a peace sign on the back, matching shorts and flip-flops. A minute later, entering the limo, he winces as the door hits his sore leg. The limo leaves Joe Robbie Stadium for a 1,000-yard trip to a nearby helipad, where two helicopters wait to take the Sanders entourage two miles to Opa-Locka Airport for the flight back to Pittsburgh.”

He showed up to Three Rivers Stadium 17 minutes prior to game time, by Brennan’s watch, but didn’t play. “He was fine,” Braves manager Bobby Cox said after the 13-4 loss. “I just didn't have the opportunity to use him.” The Braves would go on to win the series in seven games, then lose the World Series to the Toronto Blue Jays in six. In the final series, Sanders hit .533 (8-for-15) and stole five bases.

He missed the next two Falcons games after the loss at Miami, yet still earned first-team all-pro honors for the second time in his career.

* * *

Sanders’ time with the Braves didn’t last long; the team traded him to Cincinnati early in the 1994 season. His early career was marked by the sort of gasconade many fans of the NFL had come to adore and many MLB executives and players had come to loathe. As a rookie in 1990, Sanders infamously drew a dollar sign in the dirt in front of white sox catcher Carlton Fisk, who had taken issue with Sanders failure to run out a pop-up. “Hey, man,” Sanders told Fisk, “the days of slavery are over.” The two came nose-to-nose and the benches cleared.

John Schuerholz, who drafted Bo Jackson and Sanders in Kansas City and later signed Sanders during his GM tenure with the Braves, says Sanders’ attitude ultimately led to the team’s “decoupling” with the speedy outfielder.

“Deion was the second-best athlete I’ve ever seen in an MLB uniform, after Bo Jackson,” Schuerholz says. “When he played for us, we felt like he was going to disrupt the opposition in some way or another every game. And he usually did.

“However, and Deion may challenge me on this [Sanders did not respond to an interview request], it didn’t seem to me that he had completely decoupled intellectually and emotionally from football. The difference between Bo and Deion, was [Sanders’] inability and disinterest in understanding the environment of baseball, the overarching expectation of baseball players to represent the team name on the front of the uniform, not the name on the back, and he had a more difficult time with that than most. It finally got to the point where, as talented as he was, it became too disruptive and too disconcerting to our on-field leadership team to have to manage through that so often.”

Sanders never stuck with any one team, and though he went on to Super Bowl fame with the 49ers and Cowboys, his baseball career was nomadic, and never reached the level it did in 1992. He played in the NLCS with Atlanta in 1993 in what would be his final MLB playoff appearance. He never hit .300 again, and only played in 100 regular-season games once, in 1997, his final full season of baseball. Since Sanders’ final game in Cincinnati, in 2001, no athlete has played in the NFL and Major League Baseball—or, for that matter, in any of the other major North American sports—in the same year.

• BASEBALL WEEK AT THE MMQB: The MMQB’s series on the crossover between hardball and football.

* * *

There are a number of theories as to why there are no more dual-sport athletes. As with most things, money is a good place to start. In 1992, Sanders was making $2.05 million as arguably the best cornerback in the NFL. Twenty-five years later, the highest-paid cornerback in the NFL (scheduled to be the Rams’ Trumaine Johnson in 2017) will earn more than eight times that.

Bobby April was the tight ends and special teams coach for Glanville’s Falcons, and went on to coach special teams for eight different teams until 2016. Over his career, April witnessed the NFL salary cap skyrocket from $34.6 million in 1994 to $155.27 million in 2016, leaving him in the unique position to compare Glanville’s handling of Sanders to how modern NFL coaches and front offices might have dealt with him.

“I don’t know what the guys I’ve worked for would do, and I don’t want to speak for any of them,” April says. “But in today’s NFL, a guy like Deion would make so much money now, there might be some pushback from people besides the head coach. They’re making a big investment in a guy and he’s not full-time for the [owner] who’s paying the bills?”

Says Schuerholz: “Because of the money we pay star athletes in baseball, and the same with the other sport, both sports are going to expect the same level of commitment and fidelity from that player that’s just difficult to provide.”

Then there’s the obvious physical limitations. It stands to reason that only a handful of athletes in existence possess the talent to play pro baseball and pro football at such a high level as to justify their participation in both simultaneously. If that weren’t enough of a qualifier, such an athlete would need the endurance, mentally and physically, to compete at the highest levels of American sports, year round.

“Just take the ability to do it, and you’ve eliminated a huge portion of the human population,” April says. “Then, to come out of football and go play a full baseball season is physically hard to do. That takes out a big chunk of remaining people. Then you factor in the mental endurance. How many people are left?”

After all that, you still have to reconcile how the changes in sports culture have impacted would-be two-sport stars. Specialization in high school sports, encouraged by the growth of offseason opportunities essential to college recruitment, have forced many young athletes to pick a sport and go full-time.

“When I was in high school,” says Glanville, now 75, “the track coach would come pull me out of the baseball game and I would go over in my uniform and put the shot, and then go back to the baseball game. That would never happen today.

“In the high schools, the coaches make you make a decision and just concentrate on that. They tell you everything you’re going to miss out on, the college camps and all that, and it’s either this or this; it can’t be both. And the parents have probably made a decision before they ever get to high school.”

Mike Farrell, National Recruiting Director for Rivals.com, can count on one hand the number of athletes who commit to play multiple scholarship sports for a Division-I powerhouse each year, as Sanders did when he committed to Florida State football, baseball and track and field in 1985.

“The sports are too specialized nowadays and require year-round attention,” Farrell says. “Between off-season lifting, spring ball, summer 7-on-7 and workouts and the football season, it is frowned upon for prospects to play multiple sports, honestly.”

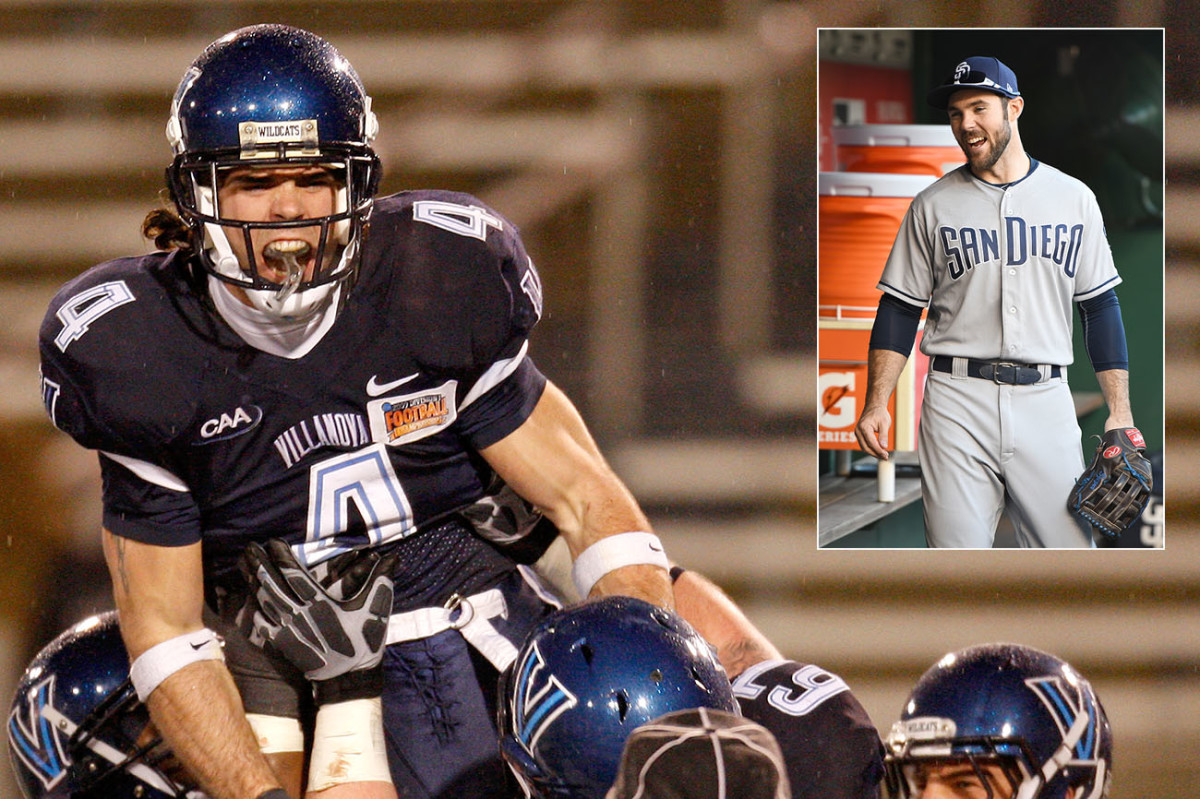

In most cases, those who commit to two sports end up settling on one; 49ers receiver Bruce Ellington first picked basketball at the University of South Carolina, then played both before deciding, at 5' 9", his football prospects were more promising. Five years earlier, Villanova football multi-purpose star and baseball slugger Matt Szczur, faced with a similar decision, chose baseball under the advisement of mentor and NFL Network draft analyst Mike Mayock, the father of one of Szczur’s Villanova football teammates. Mayock told Szczur that, despite the likelihood he’d be a third- or fourth-round pick in the NFL draft, he ought to pursue baseball for the career longevity.

“I thought I probably would have been better off in the NFL, but you can be pretty much crippled in one play in football, so I just knew [baseball] was a better decision for me,” says Szczur, who won a World Series ring with the Cubs last fall and now plays the outfield for the San Diego Padres. “When I was growing up, my parents just told me to do everything and find a sport I like and I liked two so I just kept at both. But I kind of look back at it sometimes—and not that I have any regrets—but I feel like if I had focused on baseball or football I might have been a better player.

Often enough, the athlete who excels at the highest collegiate level of two sports has the decision forced upon them. Seahawks quarterback Russell Wilson’s falling out with coaches at N.C. State was in part because of his desire to compete in baseball and football at the same time. No. 1 overall pick Jameis Winston, who pitched and played quarterback at Florida State from 2013-14, signed a four-year, $23.35 million deal with the Buccaneers in 2015 that included the condition that he not pursue a career in baseball.

Even Szczur, who wasn’t the same level of prospect as either quarterback, accepted a $500,000 bonus with the Cubs in 2010 if he promised in writing not to pursue a football career or attend the NFL combine.

“The only scenario I could imagine, with a guy playing both, would be if a pitcher like [the Giants’ Jeff] Samardzija played in the NFL on his days off … then again, pitchers are working on something every day,” Szczur says. “I just don’t think there will ever be a Deion or a Bo just because of how demanding both sports are now.”

* * *

Looking into the crystal ball of potential dual-sport revolutionaries, there is but one young man in the high school class of 2018 carrying the expectation of stardom in both football and baseball, with the stated desire to pursue both at the next level. Jordyn Adams, of Cary, N.C., committed in early July to play both sports at the University of North Carolina, where his father is the defensive line coach.

Adams’ father, Deke, was a starting linebacker for the University of Southern Mississippi in the early ‘90s. His mother, the former Alexis Hall, was a 1,000-point scorer for USM’s basketball team during the same era. Despite having never played high school basketball, Adams was featured on SportsCenter last summer for a thundering dunk over a classmate in gym class, but his mark has been made in football and baseball. A rising senior, he transferred to Green Hope High in Cary last winter and hit .494 with 26 stolen bases in 24 games as a centerfielder and shortstop, garnering team MVP honors. Last fall, at Blythewood High in Columbia, S.C., he threw for 2,350 yards and 24 touchdowns, and rushed for 793 yards with 11 TDs, but committed to UNC as the 24th-ranked wide receiver in the 2018 class, a four-star prospect.

The baseball diamond is where Adams stands to earn the most money at the moment. PerfectGame.org, a site that ranks national baseball prospects, lists Adams in their Top 250 for the draft class of 2018. In games for his summer team, the Diamond Devils of South Carolina, and for Green Hope High, Adams has flashed a brand of athleticism not often seen on the base paths.

“He had some trouble hitting the breaking ball just because he hadn’t played baseball since the summer, but he’s just an unbelievable athlete,” says Green Hope coach Michael Miragliuolo, a 22-year high school coaching veteran. “We were in a 1-0 game in April with the TCU head coach watching us, and Jordyn stole home after the catcher caught the pitch and threw it back to the pitcher. He beat the throw back home.”

TCU coach Jim Schlossnagle, who is 642-301 with four consecutive College World Series appearances, asked Miragliuolo if he thought TCU had a chance to recruit Adams for baseball and football (said Miragliuolo: “I don’t think so.”). Miragliuolo says one NL East scout told him he thought Adams would be picked in the first three rounds of next summer’s amateur draft, but there was widespread concern he’d turn down the opportunity. Adams himself is non-committal: “Right now my plan is to go to UNC, but if I get drafted high my family will sit down and talk about it,” he says.

Looking beyond the draft, several college coaches recruiting Adams employed what has been a common technique: discouraging in casual, inexplicit terms multi-sport recruits from pursuing two sports. But when Adams narrowed down his decision to five schools, cutting Ole Miss, South Carolina and Virginia Tech, among others, he factored in a football staff’s openness to a college baseball career.

“There were teams that beat around the bush but none really flat-out said it,” Adams says. “I really wanted to do both, so that factored heavily. They would say, You can play both, but it would be hard for you to learn the playbook and be gone in the spring for baseball.”

UNC was all in. During Adams recruitment they presented the 17-year-old with a mock schedule, detailing what his day to day would look like during different times of the year as a two-sport athlete in Chapel Hill. The logistics are daunting; he runs the risk of stunting his development in football by skipping spring ball, and in baseball by missing summer and fall opportunities.

Supported by his parents and his older brother, a sports management major at Winthrop, Adams made the choice to join his father with the Tar Heels. In the meantime he’s playing summer baseball, participating in MLB development showcases, and working out in preparation for his first football season as a wide receiver at Green Hope. He has considered the possibility of one day playing both pro football and baseball.

“Deep down inside, I feel like I could do that if I got the opportunity,” he says. “But realistically? No.”

• Question or comment? Email us at talkback@themmqb.com.