The ultimate competitor

Al Oerter died last Monday. The New York Times ran a good piece on him in its obituary section. Aside from that, there was minimal coverage, at least in the papers I looked at. Sports sections I saw gave his death a quick mention.

Joe Williams, the columnist for the old New York World-Telegram once wrote, "Fame is as fleeting as a ferryboat shine." A shoeshine cost a nickel on the Staten Island Ferry. The guy would run a rag over the shoes, that was about it. First time you took a few steps on dry land, there went the shine.

Al Oerter deserved more mention. He was the greatest competitor I ever saw.

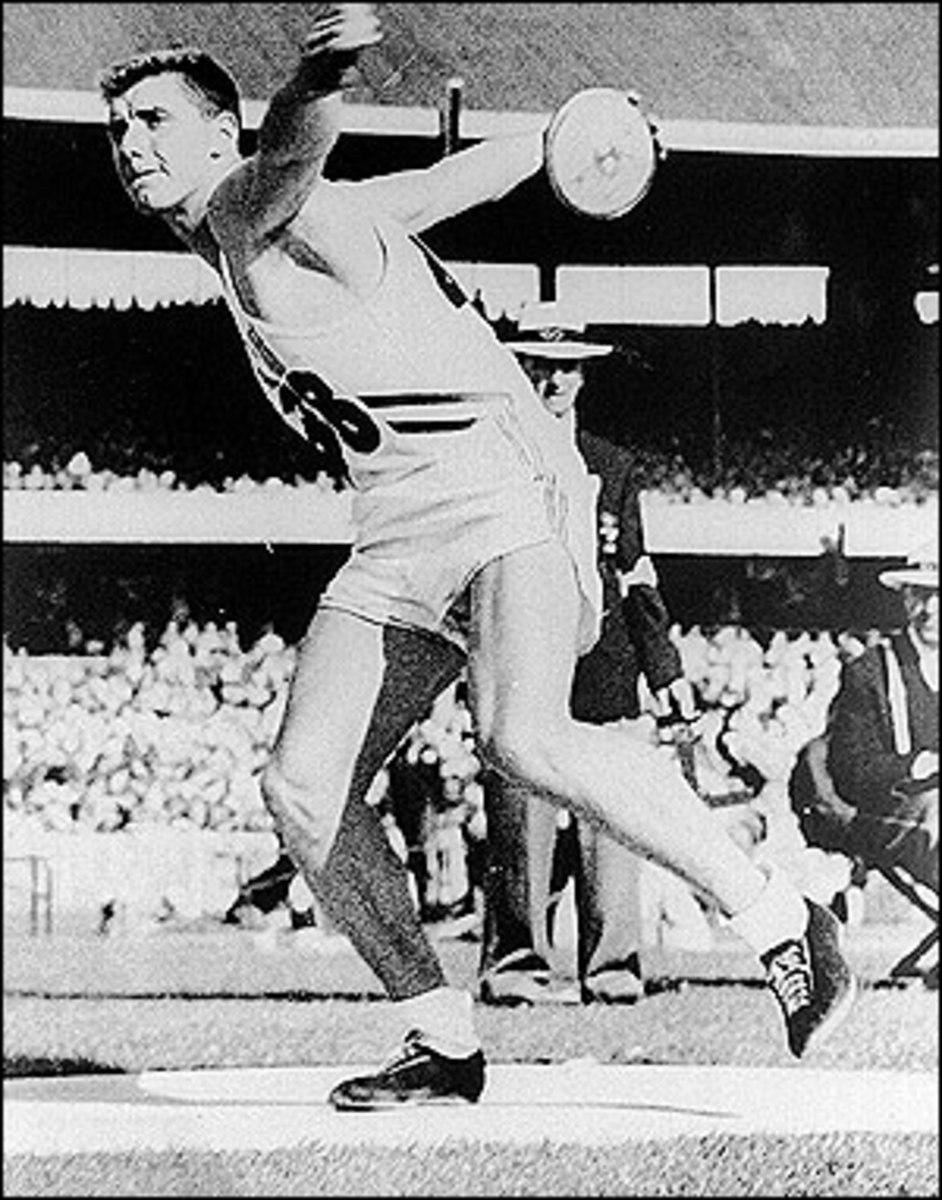

When I started covering sports in the New York area in 1960, Long Island could boast two great athletes, Oerter and Jim Brown. Oerter's specialty, the discus, was a bit more obscure than that of the great Cleveland Browns' star, but no less impressive. He had won the discus in the '56 and '60 Olympics, each time competing as an underdog to a world record holder. He would go on to do it twice more, in '64 and '68. In each of his four triumphs he set an Olympic record. In 1984, attempting a comeback at age 47, he pulled a calf muscle and lost out in the Olympic trials, but he was throwing the disc 40 feet farther than he did to win his first gold medal.

Before the Tokyo Olympics in '64 I had gotten to know Oerter pretty well, from covering local track meets in the New York area. I always enjoyed talking to him, a blond giant with a boyish shock of hair in front. Intelligent, introspective, always edgy when competition approached, he was a good guy to go to when you wanted something put into perspective.

The Tokyo Olympics was the first big assignment I covered, all by myself, as a newspaperman. I knew I would be doing plenty of stuff on Oerter, but I wondered what kind of mood he'd be in because six days before the competition began he slipped on some wet concrete in the discus circle and tore cartilage on the right side of his ribcage. The stretching motion involved in the throwing made it a terrible injury for a discus man.

There had been internal bleeding. The team doctors told him to forget the Olympics and not throw for six weeks.

"These are the Olympics," Oerter said. "You die before you quit."

Ludvik Danek of Czechoslovakia had just broken the world record. He was the favorite in the event. There was doubt whether or not Oerter would even compete.

I remember sitting in Oerter's room at the Olympic Village two days before his competition was scheduled to begin, watching him staring endlessly out the window, at the groups of athletes coming and going. He was the kind of person who didn't appreciate chit chat, certainly no questions about his physical state. I knew that anything that began, "How do you feel..." would be met by an icy stare. I saw it in his press conferences. Besides, I didn't have to ask. I could see for myself.

"Sometimes he'd hold a discus," his roommate, Harold Connolly, the hammer thrower, had told me. "He'd look at it and shake his head, and he'd wince and go back to staring out the window."

I asked Oerter how much he knew about Danek. He shrugged.

"Tall guy," he said. "Kind of narrow shouldered. I still don't know what kind of a competitor he is."

I mentioned that he was supposedly throwing well above his world record in practice. He looked annoyed.

"After two Olympics you get used to these stories about the fabulous practice throws these guys are making. Most of the time they foul when they get them off, and that brings the distance up, but nobody's calling fouls in practice. And the people who spread these rumors never mention that."

On the first day of the track and field competition I had come early and done a little scouting trip through Tokyo's Olympic Stadium and the press areas, which I understand would be impossible nowadays, with the tight restraints put on the media. I discovered a wonderful thing, the little room in which the medalists were brought after their competition and before they took the victory stand. Would I be thrown out if I just walked in and pretended I belonged? Well, not right away.

The natural politeness of the Japanese officials overcame their suspicion, and for at least a few days I got to see some incredible things. I saw Bob Hayes, singing a little song and doing a victory dance, all by himself, after his triumph in the 100 meters. And I got a raw look at Oerter, whom I had seen pacing the discus area like some kind of animal before each of his throws, and then finally ripping the tape off his side and coming from behind to beat Danek on his final heave. After his throw he doubled over in pain.

He was still wired when he got to that little room. He smashed the side of his hand against the wall and then, and I'll never forget this, threw back his head and let out this one, wild, ear-shattering roar that caused a few worried officials to pop their heads in, fearing someone was being murdered. Of course, the beer might have had something to do with it, too. Danek had brought a case of Czech beer onto the field, to celebrate his expected triumph. Oerter helped him drink it.

I don't want to get into some kind of philosophical treatise on the meaning of the true competitive spirit, because somehow it might cheapen it. There have been great competitors in many sports. To me, Oerter was the greatest.