This One's For Hep

Ben Roethlisberger keeps one copy of the poem folded in the console of his car. He keeps another framed above the desk in his house. He had a third laminated for the inside of his locker, just in case he ever needs to recite a line before wind sprints.

Success is failure turned inside out;The silver tint of the clouds of doubt;And you never can tell how close you are,It may be near when it seems afar,So stick to the fight when you're hardest hit; It's when things seem worst that you mustn't quit

The poem, entitled Don't Quit, is standard motivational fare, the kind that football teams silk-screen onto T-shirts during training camp. But the words are not nearly as important to Roethlisberger as the man who used to read them aloud. Terry Hoeppner taught Roethlisberger the poem long before either of them really needed it. When Hoeppner was the coach at Miami (Ohio) University and Roethlisberger was his quarterback, Hoeppner would recite it until his players rolled their eyes.

Then, in 2006, the poem took on new meaning. After Roethlisberger suffered multiple facial fractures in a June motorcycle accident and Hoeppner suffered a recurrence of a brain tumor, Don't Quit became a mantra for a quarterback and a coach both plagued by clouds of doubt. During one of many hospital visits, Roethlisberger and Hoeppner struck a pact: If one of them made it back onto the field, so would the other. "We talked about it a lot," Roethlisberger says. "We even called ourselves the Comeback Kids. We were going to return -- together -- and be successful together."

On June 19, 2007, Hoeppner died of complications from the brain tumor, leaving behind a wife, three children and four grandchildren. Roethlisberger, having lost his partner on the comeback trail, decided he'd play the 2007 season for both of them. Of course, he has other motivation too. Last year, in addition to the motorcycle wreck, he underwent an appendectomy, suffered a concussion on the field, threw 23 interceptions, missed the playoffs and fell from the ranks of the NFL's top quarterbacks.

But Roethlisberger is at his best when relegated to the margins, as he's proved ever since he was the third quarterback taken in the 2004 draft. So he doesn't want anyone to notice that the Steelers are 5-2 this season, have outscored opponents 184-91 and have climbed back into the conversation in the AFC. Despite having a rookie coach, Mike Tomlin, the Steelers don't look much different from other recent Pittsburgh teams. Vicious defense? Check. Battering ground attack? Check. The main difference is the quarterback's suddenly expanded role.

Under Ken Whisenhunt, the Steelers' offensive coordinator until he was named the Arizona Cardinals' coach last January, Roethlisberger was given the game plan and basically told not to muck it up. Under Bruce Arians, Whisenhunt's successor, the quarterback helps create the game plan and is encouraged to tweak it when he sees fit. "It is definitely a change," Roethlisberger says. "It gives you a lot more confidence to know that your coach believes in you."

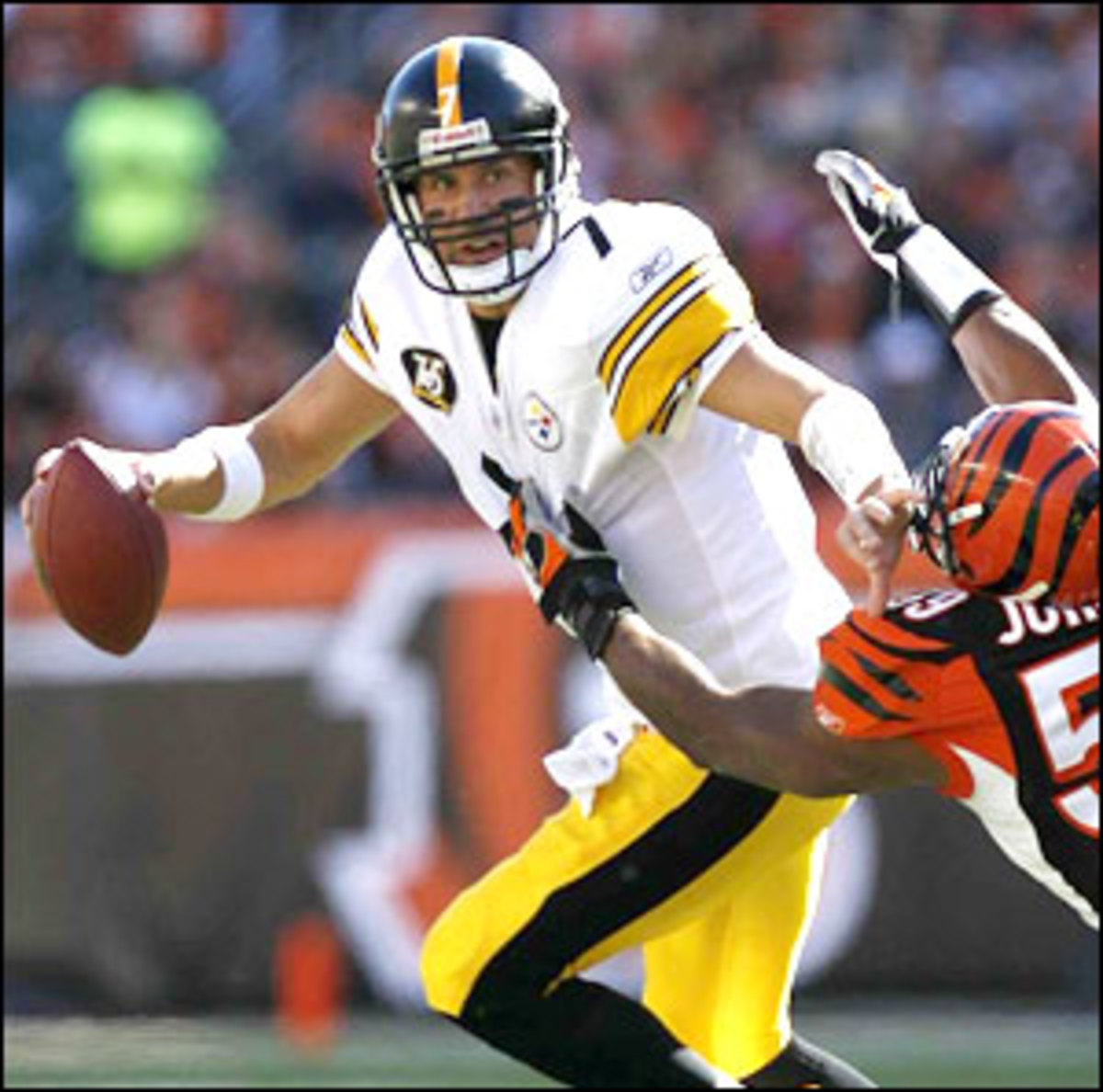

The Steelers are not quite in the class of the Patriots and the Colts this season, and Roethlisberger is not yet in the same class as Tom Brady and Peyton Manning. But he is himself again. Over Roethlisberger's first seven games last year (he missed the opener), he had seven touchdown passes, 14 interceptions and a 72.2 rating. This year, in seven games, he's thrown 15 TDs and just six interceptions, and his rating is 102.2. He looks bigger than he did last season but just as nimble -- still able to sidestep pressure, skip out of the pocket and throw on the move.

His only regret is that Hoeppner is not around to nitpick his footwork. "He always used to tell me I was overstriding," Roethlisberger says. "I think about that every time I miss a pass. So I guess that means I think about him every day."

They met in the summer of 1999, when Hoeppner was in his first year as coach at Miami and Roethlisberger was coming off his junior year at Findlay (Ohio) High, where he'd spent the season as a receiver, catching passes from his coach's son. At Miami's football camp for high schoolers, Hoeppner noticed that the big wideout also threw a pretty nice pass.

Findlay's coaches had noticed too. Roethlisberger was the jayvee quarterback as a freshman and sophomore, and he earned the varsity job in his senior year. After he tossed six touchdown passes in his debut, against Elida High, Hoeppner hurriedly offered him a scholarship. By the time Ohio State called the following month it was too late.

"The relationship between Ben and Terry was like father-son," says Shane Montgomery, an assistant under Hoeppner at Miami and now the RedHawks' coach. "Actually, it was beyond father-son." When Roethlisberger left Miami for the NFL after his junior season, Hoeppner accompanied him to the draft ceremony in New York City. After Roethlisberger joined the Steelers, he would call Hoeppner on the Friday before every game. And when Roethlisberger crashed his motorcycle on June 12, 2006, Hoeppner drove from Cincinnati to Pittsburgh and camped out in the quarterback's room at Mercy Hospital.

By then Hoeppner was the coach at Indiana. Six months earlier doctors had removed a tumor from his right temple, but he'd been back on the field for spring practice. If he could recover, so could his old quarterback. "You are going to be O.K.," Hoeppner told Roethlisberger in the hospital room. "You are going to be great."

They both spent the fall of 2006 shuttling from football fields to doctors' offices. Roethlisberger had the appendectomy in September and suffered the concussion in October. Hoeppner's second brain tumor was diagnosed in September, and he had another operation shortly thereafter. He returned to the Hoosiers' sideline two weeks later. Both men finished out their seasons, neither too successfully: Roethlisberger had a career-low 75.4 passer rating as the Steelers went 8-8 and missed the playoffs; Hoeppner's Hoosiers finished 5-7, and Indiana failed to make a bowl game for the 13th straight season.

Roethlisberger, fully mended, participated in the Steelers' minicamp last May and took a trip to the West Coast in early June. He was in L.A. when Hoeppner, 59, slipped into a coma. Doctors told the Hoeppners to call everyone in the family. Terry's son, Drew, called Roethlisberger.

The quarterback chartered a flight from Los Angeles to Bloomington, Ind., and drove to the hospital. He sat by Hoeppner's bedside, just as Hoeppner had sat by his the previous summer. "It was so right that he was there," says Hoeppner's wife, Jane. "It was so comforting."

Less than a week later, on June 19, Hoeppner died. Roethlisberger, back in Pittsburgh by then, chartered another flight to Bloomington, this time for the memorial service. Several of his former Miami teammates were in Pittsburgh and hitched a ride on his plane to pay their respects to Hoeppner. "That flight was a chance for all of us to be together and reminisce about Coach Hep," says Martin Nance, a former RedHawks receiver now on the Minnesota Vikings' practice squad. "I'll always appreciate that Ben gave us that experience."

Roethlisberger does not believe he will ever relate to another coach the way he did to Hoeppner. Who else would trust him so implicitly? Who else would support him so thoroughly? Who else would have given him a scholarship based on one game?

Bruce Arians does not give out scholarships, but he does deal in trust and support. For the past three years he was the Steelers' receivers coach, which meant he usually studied Roethlisberger from 20 yards away. But when the Steelers hired Tomlin to succeed Bill Cowher as coach last January, Arians was promoted to offensive coordinator. He was charged with spreading the field, incorporating the tight ends -- and playing a little golf with Roethlisberger on the side.

One day in May, Arians and Roethlisberger were coming off the 7th green at Treesdale Golf & Country Club in Gibsonia, Pa., discussing formations, when the coach stopped talking about pieces of the puzzle and drew the big picture. "I want you to know something," he said. "This is not my offense. From now on this is your offense."

Roethlisberger had been waiting to hear those words since he left Coach Hep and Miami. For the three previous seasons the Steelers had been Cowher's team, and the offense Whisenhunt's. Roethlisberger would run the system, not question it. Under Whisenhunt, Roethlisberger typically got the game plan when he arrived at the team facility on Wednesday morning. Under Arians, Roethlisberger is at the facility on Monday and Tuesday helping to create the game plan. The final draft is faxed to his home on Tuesday night. "It feels great to know your coaches have trust in you and will sit down and talk to you," Roethlisberger says.

Arians picked a strange time to let Roethlisberger loose. The quarterback was coming off his worst season. But here was a chance to show trust, to offer support. Arians basically handed Roethlisberger the playbook last spring and let him edit it. Roethlisberger slashed some plays and renamed others, coming up with terminology that is easier for him to spit out in the huddle. He used acronyms and word associations. A Post In Comeback route, for instance, became PIC.

In training camp Roethlisberger went 12 practices without an interception. Coaches compared him to a pitcher working on a no-hitter. Charlie Batch, the Steelers' backup quarterback, stood on the sideline and said to himself, Ben is back.

In Week 1 of the season, at Cleveland, Roethlisberger called protections for the first time in his pro career and was free to change plays at the line of scrimmage. He responded with four touchdown passes as the Steelers trounced the Browns 34-7. "He's becoming a Peyton Manning-type quarterback, making calls and checks," says Browns defensive end Orpheus Roye.

Roethlisberger does not like flattery. He prefers to be told that his passing yards are down and his fantasy ratings are low and that someone, somewhere, is saying he'll never be the same. "I like being the underdog," he says. That might sound unlikely for a quarterback who won a Super Bowl in just his second season, but at 25, Roethlisberger has already traced the full arc of sports celebrity: rapid rise, dramatic fall and now rustlings of another ascent.

Teammates who were skeptical of him during the rise were inspired by how he handled the fall. When the Steelers went 15-1 in 2004 and won the Super Bowl the next season, Roethlisberger was probably given more credit than he deserved. But when they went 8-8 last season, he unquestionably shouldered more than his share of blame. "We didn't want him to take the brunt of it, but he did anyway," says tackle Max Starks. "He stepped up and took the responsibility on his own accord. He became that seasoned veteran. He is now ready, finally, to assume the leadership position here."

In years past Roethlisberger could barely be heard over running back Jerome Bettis and linebacker Joey Porter, Pittsburgh's loquacious leaders. Now that Bettis has retired and Porter is in Miami, Roethlisberger's is one of the few familiar voices left. The Steelers need him to speak up.

Before a game against San Francisco in September, as the Steelers stretched on their half of Heinz Field, Roethlisberger ran from one teammate to another, shaking everybody's hand before kickoff. After the game he waited in the tunnel to the locker room to make sure everybody was inside for the postgame meeting. "When we got him, he was a young guy thrust onto a veteran team, and he was given a pretty short leash," says Bettis, now an NBC analyst. "But the new staff has given him more of the reins. He's been given input. And whenever you're given input, it gives you ownership. You can see that carry over to the way he plays."

Arians and Roethlisberger talk about formations in the lunch room, the training room and the office hallway. Their offense may still need work, but their rapport does not. "I know how much Coach Hoeppner meant to him," Arians says. "That's not a relationship we have yet. I don't know if we ever will. But I hope it grows into that."

On Oct. 13, before Miami played its homecoming game against Bowling Green, the RedHawks held a ceremony to retire Roethlisberger 's number 7 jersey. He stood on the field, his parents on one side of him, Jane Hoeppner on the other. "The big unspoken was who was not there," Jane says.

Before the ceremony Jane presented Roethlisberger with another jersey, one that he had been trying to find for years: the old number 20 that Hoeppner wore as a defensive back and halfback at Franklin College. "Terry's presence was so great that day," Jane says. "We both sensed it."

Fittingly, Roethlisberger was not the only one being celebrated. Miami also honored Hoeppner with a plaque that will hang inside the Cradle of Coaches Plaza at Yager Stadium, alongside those commemorating such illustrious predecessors at Miami as Paul Brown, Woody Hayes and Bo Schembechler. Jane was given a replica of the plaque for her house.

She still lives in Bloomington and keeps a number 7 Steelers' jersey on her wall. Every month or so she sends Roethlisberger a box filled with mementos that her husband would have wanted him to have. She tries to watch the Steelers on television but usually gets the Colts' broadcast, so she monitors Pittsburgh's scores on the Web. Jane Hoeppner is planning to take her children to Heinz Field to see Roethlisberger play the Bengals on Dec. 2. By then the Comeback Kid just might be the comeback player of the year.