SI Flashback: Have I Got A League For You!

Issue date: February 7, 2000

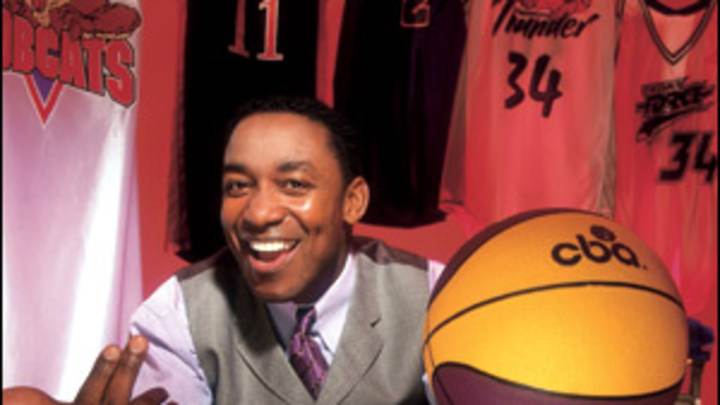

In the Old Testament, the Book of Isaiah is filled with messianic hope. In the front offices of the Continental Basketball Association, the book on Isiah Lord Thomas III is that he's something of a savior too. How does the former Detroit Piston account for his evolution from point god to the Profit Isiah? "Basically, you become a brand," he explains. "Isiah is a brand. It's a brand that's accepted internationally. But what the brand really [represents] is credibility, trust, loyalty. Now, if you can put a credible business behind that...." The brand flashes his famous smile. It's still bright enough to blind a ref.

In October the brand bought the CBA, paying $10 million to take over a league in which seven franchises had folded over the previous two years. At first glance it didn't look like Thomas's best move: Last season the nine surviving franchises together lost more than $2 million. Although attendance was growing -- the average draw of 3,809 per game was a league record -- the figure concealed a more dire situation. "Isiah saved the league," an assistant at one of the most financially troubled teams says. "Three teams stayed in business last year just because of rumors of this deal. If they had folded, no more CBA. You can't play with six."

Taking over failing businesses is nothing new for Thomas. In 1992, while still a Piston, he and a partner bought the bankrupt American Speedy Printing Centers. Today it's the fourth-largest quick-printing chain in the U.S. "Turnarounds are very interesting," says Rick Inatome, a business associate of Thomas's. "Momentum is everything, and Isiah is a mastermind of momentum."

Just as he did with Speedy Printing, the CBA's new owner immediately started calling on troubled franchises. He huddled with the front-office staffs of the Connecticut Pride and the Quad City Thunder, and he reassured corporate sponsors of the Rockford Lightning and the Yakima Sun Kings. "One thing Isiah has learned is, there are many forms of capital in business," Inatome says. "Both of these deals required social and charisma capital."

During a stop in South Dakota in November, Thomas projected his star wattage and major league glamour on Terry Schulte's Chevy dealership, which sponsors the Sioux Falls Skyforce. "That's a sharp outfit you got on there," Schulte said, noting Thomas's subtle country-squire ensemble: a herringbone jacket of russet tweed over a five-button caramel-colored waistcoat. "You didn't buy that in Sioux Falls, I can tell you that."

Inatome is right: Already the momentum seems to have shifted. After half a season under new leadership, CBA attendance and corporate sponsorship revenue were up 10% over last season. Thomas predicts that the league will even show a modest profit this year. He says that more than 40 cities have contacted him about joining (in many cases, rejoining) the league, and he can now talk seriously about creating regional rivalries, with Bridgeport (Conn.) and Springfield (Mass.) to join Hartford in New England; Detroit, Flint (Mich.) and Gary (Ind.) to add a few more notches in the Rust Belt; Anaheim, Fresno and Pomona, Calif., along with Everett and Spokane, Wash., to hang on the Pacific rims along with the Sun Kings. Even Wilkes-Barre -- whose Barons were one of the original teams in the league when it began business 54 years ago as the Eastern Pennsylvania Basketball League -- is ready to lace up the Chucks and try it again.

Thomas is not without competition in this vast expanse of what he calls "emerging domestic sports markets." If you're the type who likes a nice league prospectus for bedtime reading, you already know about the IBL (the brazenly ambitious International Basketball League) and two leagues still on the drawing board: the CPBL (the delightfully oxymoronic Collegiate Professional Basketball League) and the NRL (the National Rookie League, with its players' curiously short shelf life). The IBL, which has been running and gunning in eight cities since November, pays an average $50,000 per player over a five-month season -- roughly twice the CBA average -- although IBL contracts forbid players to accept NBA call-ups. The CPBL and the NRL hope to tip off in the next two seasons.

NBA commissioner David Stern has added his voice to this chorus, going on record about his league's need for its own minor league, one he hopes to have in place within the next 18 months. What could this mean for the CBA, which has been the NBA's affiliated developmental league for 20 years, operating under an agreement that covers player call-ups, referee training and substantial subsidies to the CBA league office? If Stern should form his own minor league, the effect on Thomas's league would be disastrous: Few players would play for CBA pay without the prospect of reaching the NBA. Perhaps in an effort to protect his investment against such a blow, Thomas has gathered a lineup of NBA stars -- Glen Rice, Jalen Rose, Damon Stoudamire and Chris Webber, among others -- interested in buying shares (which would never exceed 49%) of expansion franchises. Such sales would bring the league (and Thomas) short-term capital and, perhaps, a crossover following of big-city fans.

Stern is noncommittal about the NBA's plans. "We continue to analyze the best minor league relationship for the NBA, and that may or may not be the CBA," he said in November, calling attention to the CBA's recent history of financial instability. But, Stern acknowledged, "because Isiah seems to be earnest and active and brings a good deal [to the table] as a manager," the NBA renewed its affiliation contract with the CBA through this season.

At week's end business between the two leagues was being conducted as usual: Swingman Mark Davis jumped from the La Crosse (Wis.) Bobcats to the Golden State Warriors on Jan. 18. But the one-year term looks a lot like a tryout for Thomas, and Stern has mused publicly -- perhaps as a negotiating tactic -- about establishing an NBA minor league in Europe. There's a sense of deja vu to this game of brinkmanship: Thomas was head of the NBA players' association during collective bargaining with the owners in the early '90s. He and Stern speak highly of each other's skills at the negotiating table. In fact, Thomas's acquisition of an entire league can be seen as a sort of homage to Stern. The new CBA mimics the business model that Stern established for the WNBA, replacing the old model (a confederation of separately owned franchises) with a single entity responsible for all league decisions.

Do these two entities, the NBA and the CBA, need each other? Logic suggests that they do, but the two men don't. "The exact form that an NBA developmental league would take is still open to question," Stern says. Thomas quixotically claims that the CBA is a "business opportunity that stands alone. If the NBA participates, that's great. If it doesn't, it's still great. If the NBA decided one day to say, 'We're not going to take players from the CBA,' I think small-town America would still want basketball."

Outside the offices of the Sioux Falls Skyforce, at the Western Mall, there's always a fresh pot of coffee for the exercisers. "We don't open the door too fast," general manager John Etrheim says, "or we might clip one." On Nov. 1 at noon, a few hours before Thomas's press conference to reaffirm the CBA's commitment to Sioux Falls, the mall was deserted except for pairs of senior citizens walking and chatting amiably. When Thomas and his entourage arrived, the exercisers passed him without a glance.

The Skyforce is, in many ways, a model CBA franchise. Season-ticket sales are strong (3,600), and the team led the league in attendance the past two seasons and at week's end was averaging a league-best 5,120 per game. The franchise has the kind of corporate fingerprint that Thomas likes: Local companies, such as J&L Harley, and national concerns with branch offices in Sioux Falls, such as Gateway computers, fill the 23 skyboxes and the courtside seats at the 29-year-old arena. And fans come a long way for the games: Mike Luken and his 17-year-old daughter, Jennifer, drive 100 miles each way from Watertown, S.Dak. They get the chance to talk on the road. They've barely missed a game in the seven years since Jennifer's mother died.

Skyforce CEO Tommy Smith, who's got the boots and the big ring and the bonhomie that go with his Nashville accent, explains the team's philosophy. He doesn't care that it would pass for heresy in the world of big-time sports. "We don't want the numbers on the scoreboard to determine whether you're having a good time," he says. "I don't believe that winning is the only thing that determines your happiness." Apparently Thomas doesn't think this is heresy; in December he appointed Smith general manager of the Quad City team as well.

When Thomas walked in, the Skyforce staff members -- including John Hovda, who dons a woolly wolf suit to become Thunder, the team mascot (a big draw for the 10-and-under crowd) -- were noticeably nervous. But once it became clear that Thomas hadn't flown halfway across the country to fire them all, they relaxed and asked the sort of questions you put to a new boss: health insurance, 401(k)s. Thomas went around the table, asking them to tell him their names and something about themselves. "I had pictures of you on the wall when I was in school," said Amy Meyer, the office manager, blushing.

Jeremy DeCurtins, an operations assistant, said he was a wide receiver on the University of Sioux Falls football team that won an NAIA Division II national championship a few years earlier. Thomas extended his hand. "Hello, champion," he said. "You know, there aren't too many of us around."

Isiah Thomas often speaks in the first person plural. Sometimes it's the royal we, and why not? How many kings had better days than Thomas did? (O.K., sure, but against the Lakers?) Sometimes it's the corporate we: Thomas as the new voice of the CBA or as the brains of Isiah Investments. But usually he seems to be invoking an actual community, one to which he belongs and on whose behalf he has chosen to speak, vividly, as if the entire collective were there with him, or at least on hold on his cell phone: the Pistons, past, present, and future; former Indiana players who still jump at the voice of Bobby Knight; all world champions who currently walk the earth. Sometimes, Thomas's we is an irresistible bit of flattery; he invariably explains the new CBA rule forbidding the double team by saying, "So what we're going to do is bring the game back to the grassroots level, where it used to be when we would go to the park, and it was five-on-five, me against you." The room grows silent for a moment as everybody in earshot who has ever touched a basketball searches his muscle memory for one single shot to put up in that ideal park Thomas has just conjured.

His sense of community is infectious. But businessmen who find themselves across the table from the new owner of the CBA should ignore the cherubic smile and the big ol' eyebrows like those of the Wise Potato Chips owl. Concentrate instead on the scar over the left eye. During a 1991 game in Utah in which Thomas was scoring at will, the Jazz's Karl Malone planted an elbow there, knocking Thomas out and opening a gash that required 40 stitches. Thomas took his stitches and returned to the game. That's the man you can't see under the makeup and the bright lights of NBC studios.

"Isiah is not a basketball player who went into business -- he's a businessman who happened to play basketball," says Bruce Stern (no relation to David), the founder of the National Rookie League. Bill Ilett, a former owner of the CBA's Idaho Stampede, sat with his fellow owners during negotiations that preceded the mass sale to Thomas, and he reports, "Isiah didn't need his lawyers."

Thomas is going to need that savvy if he hopes to stabilize a foundering minor league and make it profitable. "You want to know a sure way to make a small fortune?" Charley Rosen, former coach of the defunct Savannah Spirits, asks. "Start with a big fortune and buy a CBA team."

But, as always, Thomas refuses to think small. "We want to be the Microsoft of basketball," he says, and he doesn't seem to be kidding. He envisions as many as 300 teams, in what he calls "tier 2, tier 3 cities." He hopes to own arenas in all of them, simulcasting games on each team's Web site. (Isiah Investments also runs Enlighten Sports, which produces Webcasts for the basketball and football teams at Georgia and Michigan.) National corporate sponsors could reach grassroots America two ways, with ads at the arenas and on the Web. The CBA and the NCAA are close to an agreement on a series of exhibition games before the start of next season. Thomas has also organized a tour this summer during which CBA players will face club teams in China, Japan, Lebanon, the Philippines and South Korea. "We'll do a WCBA, too," he says.

One early reason to believe in Thomas is that so far, he has gotten the basketball end of it right. Immediately after buying the CBA, he announced rules changes. This would be a suit-and-tie league; no surprise there, given Thomas's snappy dress. The playoffs would be single-elimination, like the NCAA tournament, with the championship game to be played on (how's this for a made-for-TV decision?) the Sunday of Final Four weekend. Best of all, from the players' point of view, is the new prohibition against double-teaming until the last five minutes of games. Now guys who actually can go for 60 have the chance to, and NBA scouts won't find that they've driven all the way to Schenectady only to watch the best scorer on the floor passing out of the double all night.

Thomas seems to be taking the CBA's role as a developmental league seriously. He and his head of basketball operations, Brendan Suhr, the former Pistons assistant (and, until October, owner of the Grand Rapids Hoops), have instituted a training program that includes daily weightlifting, cardiovascular workouts, and drills to improve ball handling, post moves and movement without the ball. Players have to shoot 3,000 shots a week, or 500 a day (100 from each of five spots on the floor). "Our primary goal is to develop players," Suhr says. He and Thomas refer to their league as the "Harvard of basketball education."

John Starks of the NBA Warriors, a onetime Cedar Rapids Silver Bullet, attests to the college atmosphere of the CBA: the rabidness of the fans, the camaraderie on the teams and the general lack of cash. "You have to stick together," says Starks. "On the road you try to find buffets, to stretch the dollar." Scoring in CBA games may have risen under Thomas, but so far salaries haven't -- the storied hunger of the CBA player is, apparently, not just metaphorical. "Go ask George Karl or Flip Saunders," Suhr says, referring to two former CBA coaches now dealing with NBA egos (in Milwaukee and Minnesota, respectively). "Some nights I bet they wish they were here, because they know the players play hard."

The rule against double-teaming certainly hasn't hurt. Halfway through the five-month season, more than two thirds of CBA teams are averaging more than 100 points a game. In a fast-paced, up-and-down game at the Hartford Armory on Dec. 4, the Pride exploded for 122 points against the Bobcats, and won by only seven. Boston Celtics head scout Leo Papile, who watched from the sidelines that day, may have groused about the rule against double-teaming -- "If a player can't spin the double," he says, "he's going to end up right back on the bus" -- but the guys on the court love it.

Thomas watched the CBA All-Star Game from the Jack Nicholson seats in the Sioux Falls arena on Jan. 18. He and Suhr drove to the game in a new Caddy that disappeared from its parking spot while they were inside. (Schulte, the auto dealer, sold it to a couple who wanted to buy a car that had carried the NBA legend.) Ten days later Thomas spoke about the difference between All-Star games at the NBA and the minor league level, but he might as well have been talking about his own experience as the new head of the CBA. "In the NBA the All-Star Game is always a showcase of talent, with great plays and slam dunks from the best of the best, but there's no sense of urgency," he said. "Here, where you have to compete to impress the scouts, every play is a life-and-death situation. It makes it a great game to watch."