Beyond basketball

"I wanted to get out there and compete again," says Holdsclaw. "Right now, I love being in Europe."

The decision to leave the WNBA and resurface in Europe is not new -- Holdsclaw did the same thing in 2004 after falling into deep depression following the loss of her grandmother, June. But this time it's not related to depression, says Holdsclaw. This time, it's about spending time with her family and getting away from the grind of the WNBA.

"Family means a lot to me," says Holdsclaw. "It's more important than a sport."

Her father, William Johnson, suffers from schizophrenia, and his moments of coherency are fewer and fewer. "My dad's not always coherent to the degree he needs to be," says Holdsclaw. "When I go to see him, sometimes he doesn't even know who I am."

And then sometimes, he does. It's those moments, Holdsclaw says, that have meant more to her than the ones spent dribbling, passing and shooting under the bright lights of the Staples Center.

Yet there's still something that pulls her back to the game. Holdsclaw, now 30, admits she never really stopped playing, continuing her cardio workouts and shooting drills even after announcing her retirement. "I said to my coach all along that I'd want to play again, and this I just couldn't turn down," says Holdsclaw, whose return to competition was in part due to the encouraging of Chicago forward Dominique Canty -- a close friend whom Holdsclaw played in the Euroleague last winter.

"Dominique said, 'Come on, let's get this championship again. You can't be done playing," says Holdsclaw. "When I got there, she was like, 'Oh my god, you're so refreshed."

Refreshed? More like on fire. Holdsclaw scored 32 points (matching her WNBA career high) and had five rebounds in an 85-72 loss to rival Polish team, Gambrinus Brno, on Nov. 7. The last time the 6-foot-2 power forward scored that many points was in 2002 when she helped the Washington Mystics defeat Seattle. Before that, she had only scored 32 one other time in non-college play, and that was when she helped the USA World Championship team defeat Brazil 94-90 in a hard-fought semifinal victory back in 1997.

"I was a little nervous,' says Holdsclaw about her return to the court. "I thought am I going to have it in workouts? Am I going to have the same passion?"

Any doubts about her love of the game and ability to physically play to her full potential -- an injury to her left knee was aggravated last spring -- have been squashed in the first five games she's played for Lotos. "I'm still young, I still got it," Holdsclaw says.

She also has something else that was starting to feel lost in the hectic schedule of playing in both the WNBA and Euroleague in the off-season -- time. It's something Holdsclaw used to feel guilty about -- missing friends' weddings, holidays with her family, birthdays. But now with many blank squares in her calendar where the WNBA used to be, Holdsclaw, for the first time since being the No. 1 overall draft pick in 1999, can spend her free hours reaching out to people.

One of the ways she's hoping to reach people is talking more openly about her experiences with depression. Most recently, Holdsclaw appeared in a DVD series titled Words Can Work, produced by medical reporter Jeanne Blake. Holdsclaw, known for being intensely private, opens up in the video about her experiences with depression from an early age, eloquently speaking about her darkest moments, refusing calls from teammates and brief thoughts of suicide.

"A few friends had the chance to see the DVD and they said, 'Wow, we know you, and even we don't know this side of you," Holdsclaw says.

The video, which is intended for young people in the sixth grade through college who suffer from depression, also has a separate component for their parents. In the video, Holdsclaw says that it was her grandmother who first noticed her depression at an early age, commenting on how she always picked out dark clothes. She also cites basketball as an outlet for her depression, playing on the court outside the housing project in Queens, N.Y., as her grandmother looked on.

Holdsclaw's most intense battle with depression hit after the death of June, who raised Holdsclaw from the age of 11 when her parents, both alcoholics at the time, were incapable of caring for her. It had been June who made sure that Holdsclaw did well in school while she was winning state championships for Christ the King High. It was June who oversaw Holdsclaw's college choice, pushing for Tennessee after hearing that coach PatSummitt's players had a 100 percent graduation rate. It was June who sat in the stands, cheering Holdsclaw on, who saved the letter Holdsclaw wrote to herself as a girl saying she wanted to be the first woman to play in the NBA, giving it to Holdsclaw to open on the day she was drafted.

"I didn't know how to handle my emotions when she died," says Holdsclaw. "At the time, it was like I was in a box and had closed myself in. It was the one time I needed help and I wasn't letting anybody in."

In Words Can Work, Holdsclaw talks about hitting bottom when she envisioned herself getting into a car and driving off the road. "That was my low point," she says. "I had things going through my head. But seeking therapy and talking to people is how I learned to handle those thoughts. I don't feel that way anymore."

The stigma surrounding depression was another reason Holdsclaw decided to participate in the video.

"Depression in the African-American community isn't really accepted," she says. "Sometimes people think you're achievements are a kind of strength. They think that because you're an MVP you're untouchable. They think they know you."

In 2004, it was Summitt who convinced Holdsclaw to return to basketball, determined to see the top scorer in the school's history -- male or female -- and the player who had led the Lady Vols to three national titles, get back on track. Holdsclaw did return, but asked to be traded. Washington held too many memories of June.

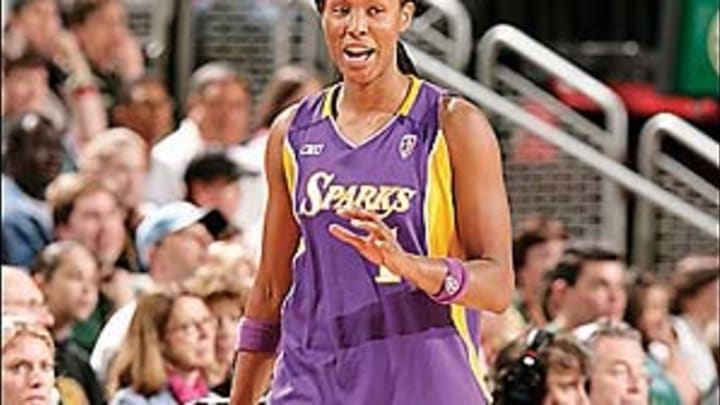

The Sparks were no doubt thrilled to add Holdsclaw to a lineup that already included center Lisa Leslie, a three-time WNBA MVP and the league's all-time leading scorer with 5,412 career points. But with L.A. losing the 2006 conference final and Leslie's maternity leave last season, the "spark" team owners Kathy Goodman and Carla Christofferson hoped to light up their franchise never fully ignited. Holdsclaw admits that not ever winning a WNBA title is her only regret.

This one missing link in the long chain of Holdsclaw's career isn't enough, however, for her to come back and play in the U.S. "Those were a lot of great years, but now it's something I'd rather sit back and watch from afar," she says. "I don't see myself suiting up again for the WNBA."

It's no secret that women's basketball players earn more in the Euroleague. The salary cap for a WNBA player is $93,000 a year. Players can make three times that much playing overseas, which is a large part of why WNBA players end up playing year-round. And women's basketball players still earn well below the amount in endorsement deals than their female counterparts in sports like tennis and golf. So speculation over Holdsclaw's true motives for scrapping the Sparks and then picking up the ball four months later overseas wouldn't be unfounded. But Holdsclaw, who signed a six-figure deal with Nike in 1999, doesn't mention money -- not once. She's just enjoying the European lifestyle.

"I like going to the supermarkets here in Poland and not understanding anything, having to find things to cook and ask around," Holdsclaw says. "It's something I want to embrace. I enjoy the culture here."

But Poland isn't her final destination. Holdsclaw, who was just settling into her new house in Atlanta when she packed up to play for Lotos, says she wants to buy a condo in Barcelona one day. She's looking forward to having her family visit her in Europe over the holidays, and is so set on the European lifestyle that she's planning on giving her first home in Atlanta to her brother.

As hard as it is to imagine the WNBA without Holdsclaw, it's even harder to imagine the sport without her, which might be enough for basketball fans. "Basketball is in my life," says Holdsclaw. "I don't want to cheat myself. God blessed me with a gift, a way to reach people, and I'm doing that." Just, of course, 5,000 miles away.

After her playing days are over, Holdsclaw hopes to coach, maybe at Tennessee, where anybody driving close to campus can take a turn on to Chamique Holdsclaw Drive (not far from Pat Summitt Street). "Me and coach Summitt, we keep in contact. I'm a proud alumni of that program, and I was glad we won last year," says Holdsclaw. "It's rich with history, and if the opportunity came about to coach there, of course I would."

Summitt, who also appears in Words Can Work, says in the video that the first time she saw Holdsclaw play she thought, "Whoever signs Chamique Holdsclaw will win championships, because she's the best player in the game."