The Road Back

Even when you are lying, helpless and twitching, on the floor of a football stadium, unable to move your limbs and unable to take a deep breath. Even when you drift to the surface from a deep, chemically induced sleep two days later and find yourself in a hospital bed, with tubes in your throat and in your groin and machines beeping in every corner of the room and your mother gently rubbing your forearm, asking you through her tears, Baby, can you feel this?Please blink your eyes once if you can feel this.

You know I love you, don't you, baby? Please blink once if you know. And you slowly blink once, though you don't remember it.

Even when you're at a rehabilitation hospital almost a month later and an occupational therapist puts a tiny, one-pound weight in your right hand and asks you to do one biceps curl with the same arm that once blocked NFL linebackers on Sunday afternoons. And you just can't do it. Even when your life is unfathomably changed at the age of 25. Even then.

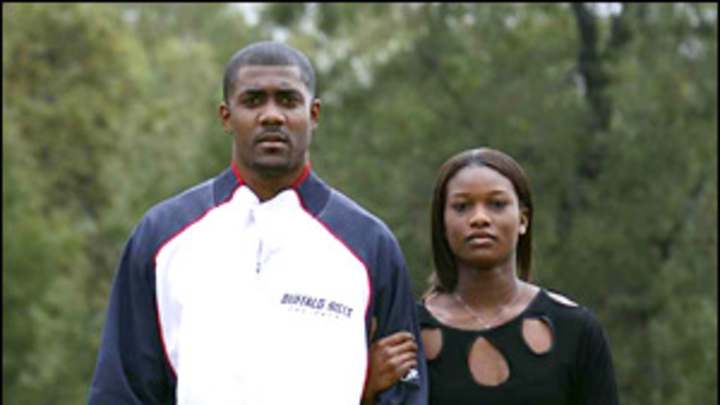

Here is Kevin Everett now, sitting at a breakfast table in a corner of the house the Buffalo Bills' tight end bought last year for his family in the Houston suburb of Humble. His fiancée, Wiande Moore, a sprinter whom Kevin met when both were athletes at the University of Miami, sits to his left, and the two of them pick at the remnants of supper. His mother, Patricia Dugas, is in the kitchen putting the finishing touches on a Christmas gingerbread house with Kevin's youngest sister, Davia, 11. His other two sisters -- Herchell, 15, and Kelli, 14 -- are sitting nearby on family room couches in front of a wall-mounted TV tuned to MTV but muted because Herchell is tapping out a social studies paper on her laptop. It is a family place at a family time.

"I'll tell you what," says Kevin. "I'm still trying to figure out everything that's happened in my life lately. But I don't think anybody has life figured out. I know you've got to take the good with the bad, and you've got to be strong. Plain and simple. Just because you get knocked down doesn't mean you've got to stay down. That's what I feel about all of this. If you get knocked down, you've got to get back up."

So he gets up. He rises from his chair and walks easily to the kitchen, opens the refrigerator and takes out a drink. Then he walks back. Simple as that. And yet not simple at all. "I'm making strides every day," he says. "Way back when I was first in the hospital the doctors were saying I might not ever walk again, and they didn't know the outcome for me moving my limbs anymore. So how much do I believe about all this? The sky is the limit. I'm going to take this as far as I can."

It is a beautiful thing, to see Everett move, a towering victory hidden in workaday acts. "I'm so proud, I want to bust out and cry every time I look at him," says his mother. "All you heard was people saying 'catastrophic injury' and 'never walk again,' and now just you look at him."

On the first weekend of the 2007 NFL season, Everett fell limply to the Ralph Wilson Stadium turf after making a tackle on the second-half kickoff. He did not get up. The stadium fell silent, an ambulance drove onto the field, and players from both teams formed a prayer circle, the nightmare tableau that can unfold in any football game but is thankfully rare. Everett, a third-year player, had suffered a fracture dislocation in his neck and severe spinal cord damage. He would be the subject of grim prognoses (many victims of his injury, indeed, do not walk again) but also exhaustive and controversial medical care, including the groundbreaking use of a hypothermia treatment that has both encouraged and divided the medical community.

Three months after his injury Everett is in the midst of a heartwarming recovery. He walks unaided at a slow, steady clip for the distance of about half a football field. (A speedier pace or a longer walk can push him off balance, though that should be alleviated as his core muscles strengthen.) He can raise his arms above his head with effort and is gradually recovering the fine motor skills in his hands and fingertips. He has lost roughly 35 pounds from his playing weight of 260, but he looks vibrant if, at 6' 4'', slender. His other bodily functions are fully intact. Five days a week, four hours a day, he has physical therapy at The Institute for Rehabilitation and Research at Memorial Hermann Medical Center in Houston, calling on a lifetime of athletic training to push himself.

"I've just tried to stay positive," he says. "The doctors say sometimes it takes a long time to come back, if you ever come back. So I kept plugging away, working hard. And every day there is a little bit more, something that starts coming back. There haven't been any what I would call milestones. Just gradual."

If he has despaired, he does not admit it. Instead, he describes only a transforming strength that has come with his injury. "I look at my life in a whole new fashion," says Everett. "You realize how blessed you are. You thank God even more when you wake up in the morning and for every little thing you have. I thank God for sparing my life and letting me be here for my family and my fiancée. I've been able to see how much people love me, and how much I love them."

He was a football player. More than a football player, in truth, a by-god force of nature. Growing up in Port Arthur, he far exceeded the weight limits imposed in youth leagues, so he bided his time until joining organized ball in junior high. He made the Thomas Jefferson High varsity as a sophomore, and in his senior year the team went 7-4 and reached the state playoffs. He played defensive end and tight end, and in one memorable midseason game in 2000 against powerhouse Ozen High from nearby Beaumont, Everett scored a long touchdown on a tight end screen pass. "I think he ran through their whole team before he got to the end zone," says Al Celaya, Everett's coach at Jefferson that year.

Everett was recruited by Miami, but one bad high school grade made him ineligible to play for the Hurricanes, so he went instead to Kilgore (Texas) College and picked up his associate's degree in a year and a half while playing two seasons of junior college football. "He came to Kilgore and went to class and took care of business," says Jimmy Rieves, who was Kilgore's coach. "A lot of talented players come to junior college and get in trouble. Not Kevin. There was no foolishness about him whatsoever."

He enrolled at Miami for the spring semester in 2003 and played two seasons at tight end on a Hurricanes team that was ludicrously deep -- Sean Taylor, Kellen Winslow, Frank Gore, Jonathan Vilma, Devin Hester -- and typically bombastic. "I met some flamboyant, cocky guys," says Everett, laughing at the memory. He took mental notes on talking smack and backed down from no one. "When he brought passion to practice, people did not mess with Kevin," says Rob Chudzinski, who recruited Everett and subsequently coached him as a Miami assistant before moving to the Cleveland Browns in 2004. "Over time he became one of the toughest kids we had at Miami."

Everett was selected by the Bills in the third round of the 2005 NFL draft. He missed his rookie year with a torn left ACL but in 2006 contributed on special teams before working his way into the tight end rotation this year. "You know what?" says Everett now. "They even put in a tight end screen." His career stretched out in front of him, a dream made real.

Just past 2:30 p.m. on the second Sunday in September, Bills kicker Rian Lindell teed up the football at his 30-yard line and paced back, ready to commence the second half of the season opener. The first player to Lindell's right was Everett -- position R5 in special teams nomenclature. He wore number 85 on his blue jersey, and in the first half, as the starting tight end, he'd caught the second pass of his NFL career, a three-yard completion from J.P. Losman. The Bills led 7-6 as Lindell's kick floated to the goal line, outside the hash marks, where it was gathered in by the Broncos' Domenik Hixon.

In kick coverage Everett was a wedge buster, a player who lines up in the middle of the field, sprints more than 50 yards and propels himself into the cluster of blockers gathered tightly in front of the return man. Wedge-busting is ferocious, demanding work; Everett was good at it. On this kick, however, he wasn't blocked at any point on the field. Just outside the Denver 20-yard line, he slipped to the right of the wedge. "They just didn't block me," says Everett. "I don't know why. I remember right before the hit, I looked over and saw [teammate] Sam Aiken. He's a wide receiver, and I beat him down [the field]. I was thinking, Man, Sam's late."

As Hixon started upfield, he angled toward the middle. Just past the 15-yard line he planted his right foot and prepared to cut outside, to his left. As he made the move, Everett arrived, shoulders squared, his body in an athletic crouch. Just before impact, Everett bent his upper body forward; Hixon dropped his upper body. The players collided violently, the crown of Everett's helmet meeting the side of Hixon's. "I've seen the play so many times, and it was the timing of it," says Everett. "I did the same thing I would do every time running down on kickoff team, got low to put my pads under his, and this one time he lowered his helmet."

Hixon was driven sideways by the blow, staggering to his right, where Aiken finished the tackle. Everett never saw that. "My body went numb instantly," he says. "I thought he kept going because it felt like he ran smack over me."

Everett's body went limp, and he crashed to the artificial turf, flat on his stomach, his head turned to the right. He was motionless except for a momentary twitch of his head and neck as he tried to lift his paralyzed body off the ground with the only muscles in his body still firing.

Fifty yards from Everett, on the Buffalo sideline, stood Andrew Cappuccino, 45, an orthopedic surgeon with specialty training in disorders of the spine and for 13 years a member of the Bills' staff under the team's medical director, John Marzo. Eleven days earlier, on Aug. 29, Marzo and head trainer Bud Carpenter had led a 1 1/2-hour spinal cord injury refresher drill at the Bills' field house in Orchard Park, N.Y. Cappuccino had nearly begged off -- "I told Bud, 'That scenario is never going to happen,' " recalls Cappuccino, who'd yet to encounter a spinal cord injury at a Bills game in his time with the team -- but Carpenter insisted. Now that drill would form the foundation for the seminal moment in Cappuccino's career. And in Everett's life.

A unit of physicians, trainers and emergency medical technicians moved onto the field and surrounded Everett. When the training staff determined that Everett had no mobility below his neck, Cappuccino was waved onto the field. He performed a quick battery of tests to assess the severity of the injury, squeezing various parts of Everett's body and asking him to respond. Cappuccino determined that Everett was quadriplegic. He turned to Carpenter and told him, "Bud, we're in the spinal cord drill."

Marzo, a former quarterback at Colgate, spoke to Cappuccino, who played football at Johns Hopkins, in the language of the athlete. "This is your game," he said to his colleague and friend. "Take the ball and run with it."

Over the ensuing seven hours, Everett would receive extraordinary, perhaps unprecedented, care across a wide spectrum of treatments from a team of more than a dozen medical professionals. As the leader of the team, Cappuccino would direct and administer not only first-rate conventional spinal cord injury care but also daring unconventional methods that pushed the standard of such treatment and potentially endangered his own career in a profession in which malpractice litigation is a real concern.

Thirteen minutes after Everett struck Hixon, the Buffalo tight end was loaded into an ambulance driven by emergency medical technician Dan Lengel. Another EMT, Rich Bartel, worked next to Everett's gurney. Cappuccino sat by Everett's head, talking to him as Everett struggled to breathe -- a difficulty that often afflicts patients with high cervical injuries. "I felt like I was going to suffocate," says Everett. "That made me nervous. That was the worst part of the whole thing. I had to stay calm and not panic. Dr. Cappuccino was right there with me, talking to me, helping me stay calm."

As he spoke to Everett, Cappuccino recalls, "I was thinking to myself, God, I have children this age. I thought about my 20-year-old son and what he would say to me if it were him on that stretcher. I knew he would say, 'Dad, don't leave me like this.' Kevin was at that moment, frankly, quadriplegic, and I made a decision to do anything I could to try to make him better."

Cappuccino knew there was a flicker of hope. On the field he had applied forceful pressure to Everett's lower extremities, from his ankles to his groin, and had detected a response that was absent with a sharp sensation such as a pinprick. This told Cappuccino that Everett had suffered an incomplete spinal cord injury, probably meaning that the cord was severely damaged but not severed.

Cappuccino then made two decisions, one that has reverberated through the medical world and one that has gone largely unnoticed but might have been just as critical.

First, he introduced mild hypothermia as a part of Everett's care. In November 2006, Cappuccino had attended a seminar of the Cervical Spine Research Society and sat in on a talk by Dalton Dietrich, scientific director of The Miami Project to Cure Paralysis. Dietrich devoted the last 10 minutes of his presentation to the potential benefits of induced hypothermia for neuroprotection -- the rapid cooling of the body to reduce metabolic demand and to prevent further damage from swelling and other inflammatory mechanisms. It is a controversial treatment that has not been established as a standard of care in spinal cord injuries and is the subject of considerable debate in the field. Partly motivated by that talk, Cappuccino had instructed the EMTs at Bills games to stock their ambulance with three bags of saline solution in a cooler.

"When we got into the ambulance, Dr. Cappuccino told me to start two IV lines with the iced saline," says Bartel. Cappuccino also pushed 3.5 grams of the steroid Solu-Medrol intravenously, and from the ambulance he instructed the hospital to prepare a solution that would deliver 600 milligrams of the steroid per hour for the next 23 hours. This is a more common treatment in spinal cord injuries, although it has not proved universally effective.

Second, Cappuccino instructed Lengel to drive to Millard Fillmore Gates Circle Hospital. Normally a player injured in a Bills game would be taken to Buffalo General, about a mile closer, but Cappuccino knew that Gates has magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) technicians on duty 24 hours a day. This is rare, and with Gates's in-house CT scanning capability it would enable swift diagnosis of Everett's injury. The hospital also is the only one in Buffalo with a neurosurgical intensive care unit, under the direction of Dr. Kevin Gibbons, 47.

Everett arrived at the hospital about 35 minutes after the hit. X-rays and CT scans showed a fracture dislocation of Everett's cervical vertebrae at the C3/C4 level, meaning that one vertebra had slipped out of alignment and was compressing against its adjacent vertebra and the spinal cord in the neck. An MRI showed that Everett's spinal cord was 70% to 75% compromised, or pinched, by the dislocation.

Cappuccino and Gibbons, assisted by senior neurosurgical resident Ken Snyder, worked to reduce the dislocation. A halo device was screwed into Everett's skull, and while he remained awake, manual pressure and traction weights were used to realign the vertebrae and remove pressure from the pinched spinal cord. Next would come 4 1/2 hours of surgery to stabilize Everett's vertebrae and further decompress the spinal cord. Both the reduction and the stabilization surgery are common practices in spinal cord injuries and clearly were vital elements of Everett's care.

Before Everett had been put under anesthesia for the operation, Cappuccino had placed a call to Everett's mother. Patricia had begun her day under the impression that she could watch her son's game on cable television. When she found that the game was not carried locally, she and her husband, Herchel Dugas, went to Mulligan's sports bar in Humble. "We were late because I spent so much time trying to get the game on TV at home," says Patricia. "When I walked in the door at Mulligan's, it wasn't 15 seconds before I saw Kevin running down the field and boom! And then Kevin wasn't getting up, and I was just standing there in front of the TV. It was so noisy everywhere, but I couldn't hear a thing. I felt like I was in a movie. And he wasn't getting up."

Patricia remembered that she kept a number for a member of the team's training staff. From the bar she punched it in, identified herself and left a message. Bills director of player programs Paul Lancaster called back shortly and told her Kevin had been taken to the hospital. It would be 90 minutes before Cappuccino phoned Patricia from the surgical suite at Gates. She can't recall his exact words, but snippets are burned into her soul: Your son is paralyzed right now.... We're taking him into surgery.... Afterward I want to do something called cold therapy. "She was upset," says Cappuccino. "She cried."

It had been a trying summer for Patricia. In August her youngest daughter, Davia, had fallen into a diabetic coma and spent two weeks in intensive care in Galveston. Now her oldest child was in a hospital, 1,500 miles away, paralyzed. Cappuccino held a cellphone to Everett's ear so he could speak with the woman he calls his Moms. Patricia heard a weak voice on the other end. "Don't worry about me," Kevin told her. "I love you."

"That was my baby," says Patricia, tears rolling down her cheeks as she retells the story three months later. "He's always been so strong, and he sounded so weak." The next morning Patricia would be on a plane to Buffalo with Moore, at the Bills' expense. The surgery went smoothly and was finished at roughly 9:30 on Sunday night. Soon, however, another dilemma presented itself.

Last June the hospital had purchased an Alsius CoolGard 3000 thermal regulation system, which uses a catheter of cooled saline inserted through the patient's femoral vein into the inferior vena cava, cooling the blood as it flows past the catheter and regulating core body temperature. The machine, which has been helpful in treating strokes and other brain injuries, had not yet been used at the hospital on a spinal cord patient, but Cappuccino felt strongly that induced hypothermia -- at a significantly lower temperature and in a more controlled environment than is possible with IV cold saline in the ambulance -- could help Everett.

There was contentious debate at the hospital. At least two doctors, including Gibbons, did not want to induce hypothermia, which can have dangerous side effects such as heart arrhythmia, blood clotting problems, pneumonia and organ failure. "Dr. Cappuccino was pushing the cooling, and it became a dynamic issue," says Snyder, 35. "He had been saying all along, 'We should do the cooling. We should do it.' "

Only when Everett started developing a low fever did Gibbons and others assent. Still, Cappuccino, who bore the ultimate responsibility because Everett was his patient, took stock of his position. A native of New York City who counts two other doctors among his six siblings and whose father was a research biochemist, Cappuccino is married to a surgeon, Helen Hess Cappuccino, with whom he has six children. His life's work and his life experience weighed into the decisions he made that day.

At one point during the debate over inducing hypothermia, Cappuccino called his wife, whose medical judgment he trusts. She encouraged him to go with his instincts. "I'm human," says Cappuccino. "Things passed through my mind. If I do this and it blows up in my face, I'm exposing myself to a lot of scrutiny. We could lose the house, lose the cars, the kids don't go to college. But I had to be able to put my head on the pillow that night and believe that I did the best job I could do."

Everett was placed on the CoolGard in the predawn hours of Monday, Sept. 10, and within two hours his body had cooled to a temperature of 91.5°. That morning Everett was able to squeeze his thighs against Cappuccino's hands. "Everybody was stunned," says Cappuccino, "including me."

At a press conference on Monday afternoon, Cappuccino intentionally painted a less positive picture. "I'm an optimist," he said to a packed house at the Bills' training facility, "but as a scientist and a clinician... I told Kevin the chances for a full neurological recovery were bleak, dismal." In retrospect, Cappuccino says, "I was [privately] cautiously optimistic, but classifying the injury neurologically at that point, chances were still that he would not walk."

Everett continued to show increased muscle movement and sensitivity on Tuesday, and by Wednesday he was removed from the ventilator. (He would remain on the cooling system for another week to maintain a normal body temperature.) "I hardly remember anything that happened in those first three or four days in the hospital," he says now. "I could tell I was better than I was on the field. That was good. And I remember I wanted to be strong for my family. I didn't want them to see me sad or crying."

Others remember too. They remember Everett's strength. His dignity. "His attitude was amazing," says Snyder. "He was so strong for his family. I think it was his attitude that allowed them to get through this. When he woke up [after having the ventilator tube removed], the first thing he said was, 'Thank you.' And then, 'How is my family?' "

Twelve days after an injury that could have left him in a wheelchair for life, Everett flew to Houston to begin rehab. Less than a month later he would be walking with assistance.

Nineteen days after Everett's injury, Barth Green, a neurosurgeon, scrolled through messages on his PDA at The Miami Project's Lois Pope LIFE Center. "I've got e-mails from colleagues telling me to stop talking about hypothermia and offering false hope," says Green. "I've got 20 e-mails from people on the religious right telling me that what took place with Kevin Everett is an act of God, not science, that it's a miracle." He shrugs. This is nothing new. A onetime wonder boy who entered college at 17 and medical school at 20, Green, 62, has studied the potential beneficial effects of hypothermia for more than two decades. He made himself the face of the hypothermia issue before Everett came off the ventilator, when he proclaimed publicly on the Tuesday after the injury that Everett would "walk out of the hospital."

The Miami Project is a prodigious operation that has raised more than $200 million in 22 years for its own spinal cord injury research. Its public faces are former Miami Dolphins All-Pro linebacker Nick Buoniconti and his son, Marc, who suffered a complete spinal cord injury while playing college football at The Citadel in 1985. Yet in the nearly three months since Everett left Buffalo, Green has become the lightning rod for those in the medical community trying to quell the hypothermia enthusiasm.

"The Miami Project made some strong statements in the aftermath of Kevin Everett's treatment, saying that hypothermia helped get Kevin Everett up walking," says Brian Kwon, 36, a spine specialist at Vancouver (B.C.) General Hospital, who is not convinced that hypothermia is helpful to patients with spinal cord injuries. "They have tremendous scientists in Miami who are doing fantastic, cutting-edge spinal cord injury research. But Kevin Everett is one patient, and there has never been a published study of the treatment he received."

Cappuccino has also felt some blowback. "There are doctors out there who think I'm some kind of monster for experimenting on a human being," he says. "There are colleagues of mine who think I'm crazy for doing what I did."

It is useful to step back from the emotions that surround Everett's case and raise two points: First, there is almost unanimous agreement among spinal cord experts that Everett received exemplary care across many treatments. "The most important thing that happened in this young man's case was that he received prompt medical and surgical attention from clinicians who knew what they were doing," says Mark N. Hadley, who directs the neurosurgery residency program at the University of Alabama School of Medicine.

Everett's care was remarkable on many levels. The Bills employ a spinal surgeon as part of their medical staff. (Marzo says that at meetings of the NFL Physicians Association in 2001 and '02 he proposed making it mandatory that the home team have a spine specialist present at each NFL game; he didn't get much support but says he will try again.) Carpenter, the head trainer, regularly runs a thorough spinal cord drill. Millard Fillmore Gates Circle was the ideal hospital, and it served Everett not only with gifted physicians but also with a tireless nursing staff that Everett thanked endlessly upon leaving.

The effect of hypothermia is less certain, in that it is difficult to assess the effect of any one element in an array of treatments. "There are a number of potential explanations for [Everett's] very thankful recovery," says Dan Lammertse, medical director of the Craig Hospital rehabilitation center in Denver. "There is no way to parse out the independent contributions of those variables."

Recovery varies widely among spinal cord injury patients. "Do we ever see patients with this amount of recovery without hypothermia? The answer is yes," says Lammertse. Meanwhile, Everett has met patients who long ago suffered injuries similar to his and are still in wheelchairs. Clearly, as an NFL player, his physical condition played a role. "His ability to tolerate the physical stress of treatment was important," says Snyder. "I wonder if we would have treated a 62-year-old obese smoker as aggressively."

Second, the hope in the medical community is that Everett's recovery will lead to funding for clinical trials on the effects of moderate hypothermia in spinal cord injury cases. Hadley says, "Did the hypothermia make a difference? It may have been of benefit, but as scientists we don't know. We need clinical trials, where multiple patients get it and similar patients don't, to see if it has real merit." The irony is that Everett's highly publicized recovery could make it difficult to recruit patients for a clinical trial in which some participants do not receive the treatment he did.

Many surgeons called for caution. Even Green says, "Don't administer hypothermia unless it's part of a whole continuum of care, like Dr. Cappuccino used it. We don't need people being cowboys out there."

Cappuccino does not waver. "I am convinced that cold therapy helped this young man," he says. "I will use it again."

For Everett, meanwhile, clinical trials and journal articles are of little import. "I know what Dr. Cappuccino did," he says. "He saved my life."

Here is familiar noise, the soundtrack of an athlete's life. The heavy crash of a weight stack falling, the grunts that come with effort, the exhortations of trainers pushing players. Everett has heard it all a thousand times. But as much as this is the same, it is also deeply different. He is in the first-floor gym at The Institute for Rehabilitation and Research in Houston. His coach is occupational therapist Lisa Criswell, and his assignment is to lift a very small pile of plates on a chest press machine, to strengthen his upper body. It is hard work. "Kevin was frustrated at first," says Criswell. "But such a jump since then."

Between sets, another therapist passes, holding a football. Everett turns his palms up, calling for the ball. The therapist tosses a soft knuckler that drops between Everett's hands and settles into his lap. "Right in the breadbasket," he says. The moment is weighted with symbolism.

Everett can live a long, full life, but he will never play his game again. "I miss it, man," he says, and then he pauses, reflecting. "I'm not sure 'miss it' is strong enough. I think about being out there every day. Even back when I tore my ACL, I realized how much love I have for this game. I'm passionate when I'm out there. I'm emotional. I talk a lot of trash.

"I felt like I had a real connection with [rookie quarterback] Trent Edwards," he says. Then comes a crooked smile. "Somebody else is going to have to run that tight end screen now."

Yet the rehab center is no place for tears. It is a humbling place where self-pity is swiftly exposed. Everett understands that power and has embraced it. "Every day I see people in here who are in what you might consider really bad shape," says Everett. "They've had something taken away from them, but they're happy, and they're working hard." A motorized wheelchair glides past. Another patient is lifted onto a soft mat for exercises, unable to do so himself. Yet another walks past Everett and shakes his hand. "Everyone here is so positive," says Everett. "A good attitude will take you a long way. Nobody promised me that I would get this far.

"I'm comfortable with my situation right now," he says. "Some people, I guess it might take them a long time to accept things. But sooner or later, you're going to have to. And then you put your faith in God and let him show you the way."

Moore, his fiancée, drives him to the rehab center in his Escalade and stays there with him. She takes notes and asks questions and seldom leaves his side, a deep expression of love. "We met a man here whose wife left him when he had a spinal cord injury," says Moore. "I could never imagine leaving Kevin. I need to be here for him. I'm thankful that we can still be together. He's alive. That's a blessing in itself."

Everett's mother cooks his meals and cares for him. His siblings treat him like a prodigal brother and clamor for a night out watching the Rockets play. (Kevin has slipped unnoticed into the Toyota Center a few times, watching NBA games from the suite of his agent, Brian Overstreet.) Phones ring throughout the house, the callers wishing Kevin well. "You learn who your friends are when something like this happens," says Everett. "I'm lucky to have people who care about me." He makes a point of praising the hospital staff and introducing them to visitors.

Everett has thought about his future. Friends have contacted him about coaching high school in Texas, and that possibility intrigues him. "I'd like to work with kids," he says. "I'm sure of that. Maybe teaching. I want to stay around football too." He says that with help from the NFL and the Bills, his medical issues have not created a financial burden.

Everett sits at a tall table in the back of the rehab center's gym, playing a game of Chinese checkers against Wiande. Pinching the marbles with his thumb and forefinger -- neither of which yet has much sensation to touch -- and moving them around the slippery game board is valuable exercise for improving his fine motor skills. The competition feeds his personality. It is as if he is in pads again. Twice today he has beaten therapist Dawn Brown, and now he is closing in on a second win over Wiande. "It's beautiful, isn't it?" he barks after one jump. "I might as well let you move twice."

At last he lifts a tiny black marble and drops it into the final slot, finishing his victory. "I'm just so good!" he shouts. "I'm like the heavyweight champ!"

He swings his legs to the side of the chair and pushes himself into open space before throwing his arms skyward, standing tall, full of life.