Fear factor

"Nobody did it like me," Goose Gossage said recently, and he's right. Over the course of his outstanding 22-year career that should finally land him in the Hall of Fame on Tuesday on his ninth try, nobody was more intimidating than Gossage, and nobody embodied the role of closer in such a viscerally frightening way. Gossage was so scary it bordered on the comic.

"From the press box," Tom Boswell once wrote, "Gossage is a relief pitcher. From ground level, eye-to-eye in his own world, he is a dragon."

Above and beyond his sustained excellence, Gossage's greatest contribution to the game was the way he reduced the sport to its purest, most primal sensation: fear. Tangible, sweat-dripping fear. The fear a batter feels standing in against a 95 mph-plus fastball. The fear a pitcher feels when he knows that an errant pitch could kill a man. This tension is omnipresent, but never was it more pronounced than when Gossage was on the mound and the game was on the line.

"I scared myself," Gossage admitted to the AP last week. "I really did. I was ferocious out there on the mound."

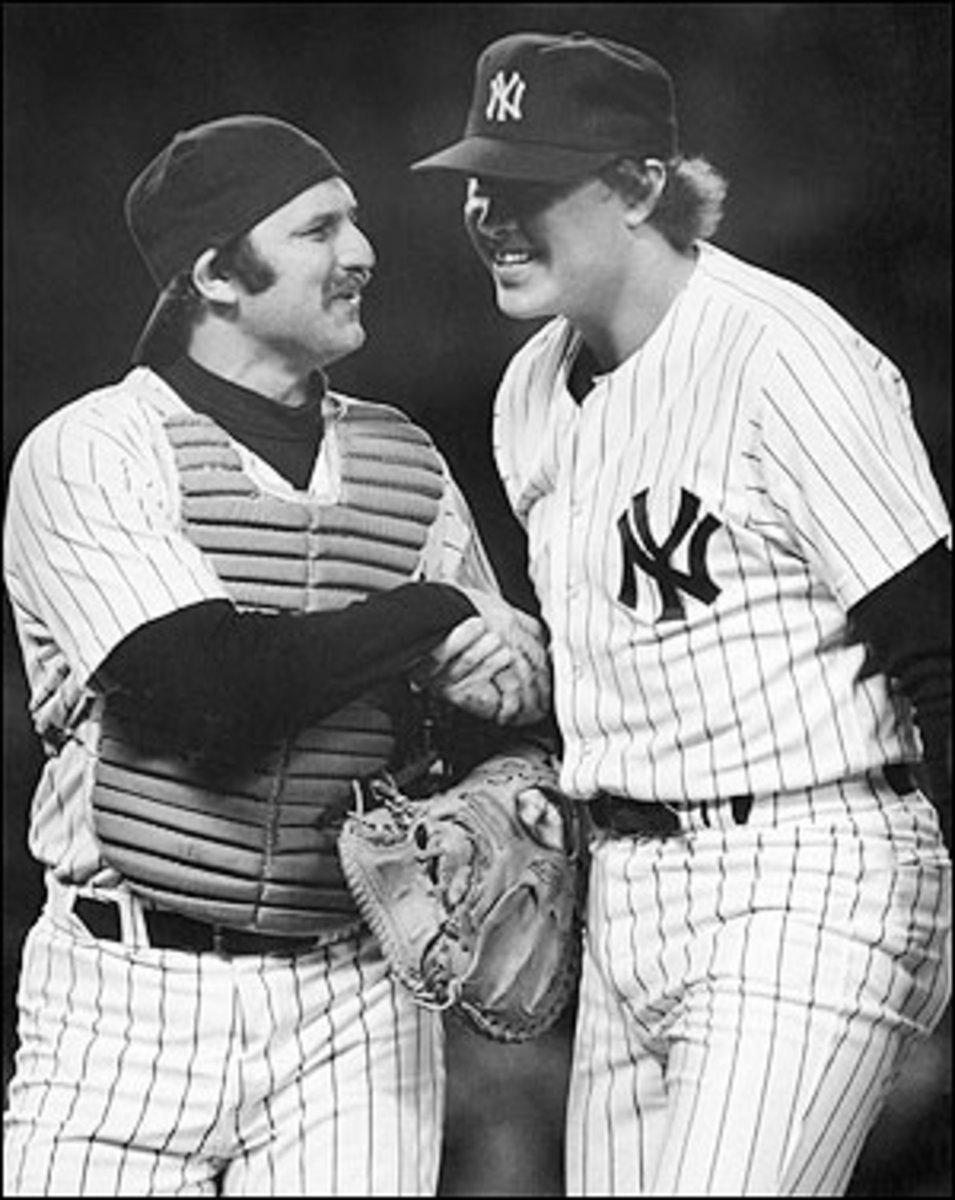

The image of Gossage unleashing fastball after fastball is one that will not soon be forgotten by those who watched him, let alone those who faced him. A hulking man who wore a villainous Fu Manchu mustache for much of his career, Gossage looked as if he was always throwing the ball as hard as he possible could. He looked like a Gashouse Gorilla from the old Looney Tunes cartoon, steam puffing out of his nose like a bull, his limbs flailing back and then forward, and then wildly off the mound towards first base.

Gossage was not the first power pitcher to excel in relief. Joe Page, Ryne Duren, and Dick Radatz preceded him. But Gossage had a better career than any of them (from 1975-84, his fastball was rated by Bill James to be the best among relievers). The best fireman relievers of the '70s (pitchers who were regularly asked to enter the game in the seventh inning) were Rollie Fingers, Mike Marshall, Tug McGraw and Sparky Lyle, pitchers who stood out because of masterful trick pitches -- sinkers, screwballs, sliders. But while Gossage used a slurve too keep batters honest, particularly right-handed hitters, he was defined by his power.

The most memorable moments of Gossage's long career involve were the major confrontations with some of the era's best players in key games, victories as well as defeats: getting Carl Yastrzemski to pop out to end the 1978 one-game playoff with the Red Sox; nailing the Dodgers' Ron Cey in the head in the '81 World Series; giving up long home runs to George Brett of the Royals in the '80 ALCS, and Detroit's Kirk Gibson in the '84 World Series.

The most important save of Gossage's career came against the Red Sox in that '78 playoff game. He had already been an All-Star reliever for two teams, the White Sox and Pirates, but had never pitched in a playoff game when he signed a six-year, $2.8 million free agent contract with the Yankees after the 1977 season.

Dubbed "The Best Team Money Could Buy," the Yankees already had an ace reliever in Lyle, who won the CY Young award in '77. Gossage's acquisition, and his then-huge contract, would only be justified if he delivered big performances in the biggest games.

The night before the playoff game, Gossage was convinced that it would come down to a confrontation with Yastrzemski, Boston's veteran star. It did. Gossage had entered in the seventh inning with a 5-2 lead, but in the bottom of the ninth it was 5-4 with two on and two out when Yastrzemski came to bat.

"My legs were shaking," Gossage later told author Dick Lally. "I'd never come close to playing in a game of that magnitude. Never had a feeling like that before. I told someone it was like being led in front of a firing squad. Yaz was the last guy I wanted to face in that spot."

Yaz, a dead fastball hitter, had struck the ball hard all day, collecting two hits, including a home run. Although in the declining years of his career, Yaz was still considered one of the best clutch hitters in the game.

"I had to calm down," Gossage continued, "so I started talking to myself. I thought, 'All right, what's the worst thing that can happen here?' And my answer was, 'I'll be home in Colorado tomorrow looking at the mountains.' Suddenly I was very calm."

Gossage's first pitch sailed high for a ball. The next one was a fastball tailing in on Yaz's hands. The veteran slugger popped the ball up in the infield and the game was over. "That pitch he threw me that afternoon," Yaz later recalled, "came in even faster than I thought."

"I can't tell you how hard I threw that pitch," Gossage remembered, "but it might have been one of the hardest pitches I've ever thrown."

Of course, sometimes Gossage got burned with his best stuff, like when Brett and Gibson took rising fastballs into the upper deck. But, like all great closers, Gossage was able to quickly forget about the defeats. "Sometimes, after a bad loss, I'm amazed that I can go out there the next day and do anything at all," he once said. "But fortunately, there's this gorilla in me that just takes over."

It didn't hurt that the Gorilla was strengthened by a fastball that lived near 100 mph.

"If I'm gonna get beat," he once explained to Geoffrey Stokes, a reporter from the Village Voice, "I want to get beat on my best pitch, not on some off-speed thing that's just supposed to set the fastball up. But what happens is, I get out there, and I throw a ball at 95 miles an hour easy, so I just gather up my strength and try humming [it] at a hundred. I'm out there, and I feel that with just a little more effort, I could throw the sucker right through the catcher -- and maybe halfway through the umpire, too.

"The thing is, it doesn't go as fast. It's pretty hard to throw a ball with one hand around your throat. And when that happens, even before everybody's turning around to watch the home run, it affects the team. It's like your kids; when they see fear in your face, they get afraid too, even if they don't know why. In the clubhouse, at the hotel, everybody's got their own personality. But when I'm out there with runners on second and third, one out, and a one-run lead, I'm responsible for the whole team."

On Tuesday, the man who scared so many, himself included, should fear not. The closers already enshrined in the Hall of Fame -- Hoyt Wilhelm, Fingers, Bruce Sutter and Dennis Eckersley -- had best make room. A Goose is flocking to Cooperstown.