Sins of a Father

The kid hated needles. But it hardly mattered. About once a week he'd roll up his sleeve, expose his shoulder and feel the cold metal plunge into what little muscle he had there. He would scrunch up his face as if he had smelled something foul and often close his eyes until the contents of the syringe emptied into his bloodstream. Then he could return to his PlayStation 2.

The injections had started in 2002, when Corey Gahan was one of the top in-line skaters in the world for his age group. At first the shots contained B-12 vitamins; soon he began receiving human growth hormone as well, and later steady doses of steroids in the form of synthetic testosterone. Both his father and his trainer, Corey says, assured him that the shots were for the best. If it stung like a bitch when the needle pierced his skin, the payoff would come when he zoomed past the competition on the track.

The prick of the needle was accompanied by a pinch of guilt; it felt, as Corey puts it, "like I was doing something wrong." But he believed in his dad, a charismatic and fiercely ambitious former high school wrestler. He also trusted his trainer, a bodybuilder who acted like a big brother. Besides, what did Corey know about the substances being injected into his body? "Testosterone cypionate, it's just a word," he says. "It doesn't have a meaning. At least not when you're 13."

When former Senate Majority Leader George Mitchell presented his much anticipated report last month that chronicled the widespread use of performance-enhancing drugs in Major League Baseball, he encouraged the discussion to be broadened beyond MVPs and Cy Young Award winners. In particular he warned about what he called "the most disturbing part of my research": the prevalence of steroids in youth sports. "Several hundred thousand young Americans are using steroids; it's an alarming figure," Mitchell told SI the day after he issued his report. "At that age, they're subject to hormonal change, and the risk to them -- both physical and psychological -- is significantly greater than it is for mature adults."

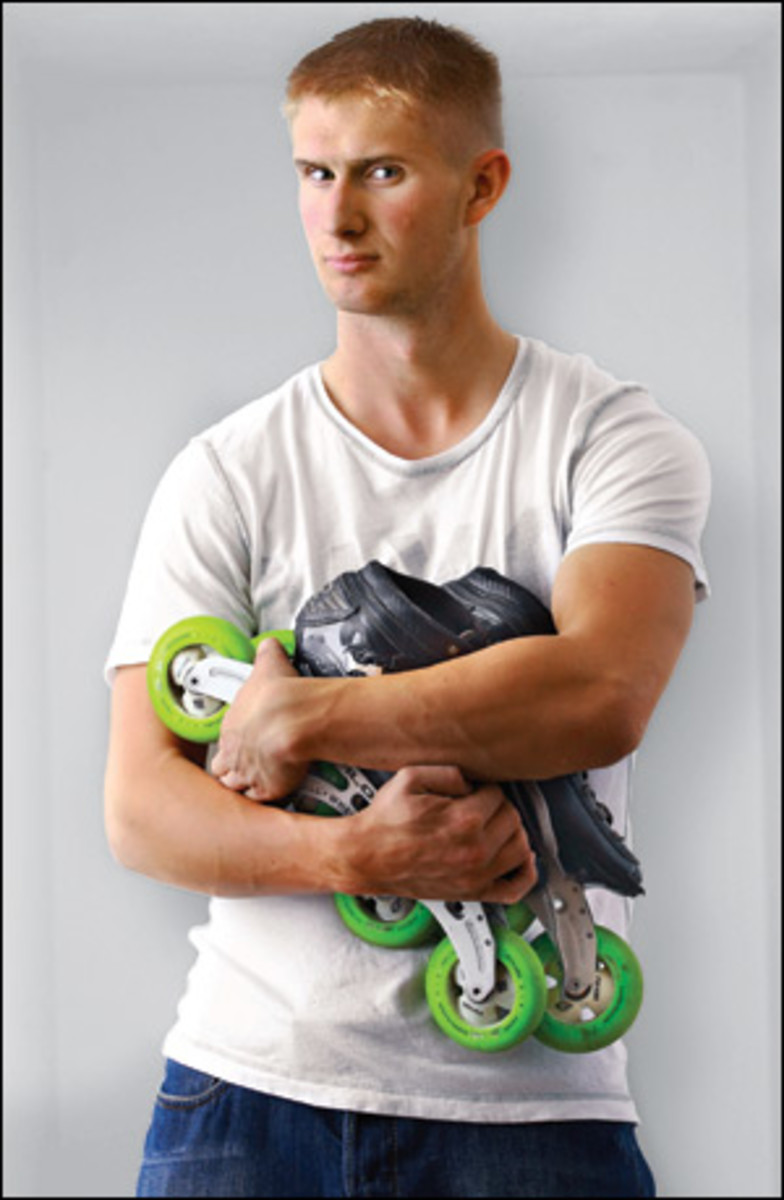

Had Mitchell wanted an embodiment of that risk, he needed to look no further than Corey Gahan. With his promising in-line skating career now reduced to videos and a scrapbook, and his estranged father serving a six-year sentence in a federal prison -- believed to be the first parent convicted of providing steroids to his own child -- Corey, now 18, represents a chilling cautionary tale of what can happen when performance-enhancing drugs poison youth sports.

Corey's story begins in Grandville, Mich., a town of 16,774 outside Grand Rapids. Early on, it was clear that he was a natural athlete, but as his peers were playing Little League baseball and Pop Warner football and junior hockey, Corey gravitated to in-line skating. His face clenched with intensity and dirty blond hair matted inside his helmet, he zipped around the track at more than 20 mph; at 10, he won his age group at Le Trophée des 3 Pistes, an international event in France. Shortly after that, Jim Gahan, who had divorced Corey's mother, Patricia Johnston, five years earlier, decided that he would move with their only son to the skating hotbed of Ocala, Fla., where Corey could train year-round with a prominent coach. (His younger sister, Casey, remained with Johnston.)

Corey would be homeschooled, first by a teacher and then on-line, and deprived of a conventional childhood, but Jim was sure that the sacrifices were worth it. The growing in-line skating community believed that the emerging sport would soon be featured in the Olympic Games. But even if not, Corey could always follow the path of other in-liners such as Olympic gold medalists Apolo Ohno and Chad Hedrick, trading in his rubber wheels for metal blades to pursue his Olympic dreams in speedskating on ice. The Gahans had little financial incentive to move to Florida -- there is no U.S. professional circuit for in-line skaters -- but Jim didn't care. He had made money in an assortment of businesses, including importing champagne. "Every parent wants their kid to be the best," says Jim, "but every kid wants to be the best."

In keeping with a recurring theme, Jim had a falling out with Corey's coach, and he hired Phillip Pavicic, a bodybuilder and gym manager, to work with his son. Early in the relationship Jim and Pavicic mapped out a training strategy for Corey, then 12. Jim says it was at this point that Pavicic recommended performance-enhancing drugs. (Pavicic declined repeated interview requests from SI.) "Corey and I sat down, had a little talk, and he said he wanted to do it," recalls Jim, 41. "I said all right."

There's disagreement about who administered the shots: Corey says his dad and Pavicic injected him, Jim accuses Pavicic and, through his lawyer, Pavicic points the finger back at Jim. Regardless, there's no dispute among the three principals on this: 12-year-old Corey was placed on a heavy-duty regimen of HgH and steroids.

Almost immediately after the cycle began, the contours of Corey's body changed. But the effects went beyond bigger biceps and calves. Shortly after his 13th birthday in May '02, Corey returned home one afternoon feeling wobbly and paranoid. He vomited multiple times. "I think I crashed on a cycle really hard," he recalls. In the aftermath of this episode, Pavicic took Corey to see John Todd Miller, a Tampa man representing himself as a doctor. According to court documents, Miller ordered blood work on Corey and found that the kid had more than 20 times the normal level of testosterone for an adult male. Nonetheless, the documents show, Miller would later begin providing testosterone to Corey. (Miller did not return calls seeking comment.)

Whatever ambivalence Corey may have had about injecting steroids, he says it dissipated when he first visited Miller. Hanging alongside various diplomas suggesting that Miller was a doctor -- he, in fact, was not -- were framed photos of prominent athletes from a variety of sports who, Corey assumed, were all seeing Miller. Corey did a double take one day when he saw 420-pound Paul Wight, better known by his WWE stage name, the Big Show. (In October 2003 Wight told Hillsborough County investigators that he received steroids and the painkiller Nubain from Miller.) "Wow, what's going on?" Corey recalls wondering. "Is [this] really how everyone does it?"

The Big Show had company. On a sign-in sheet from Aug. 27, 2002, obtained by SI, Corey's name appears between that of Randy Poffo (a.k.a. the since-retired professional wrestler Macho Man Randy Savage) and that of the late wrestler Brian Adams (a.k.a. Crush). SI also obtained invoices and receipts for drugs from Miller's clinic, signed by Poffo, who could not be reached for comment. Records indicate that other Miller clients included former major league pitcher Anthony Telford, who admitted to investigators that he had purchased testosterone from Miller, and late WWE wrestlers Chris Benoit and Eddie Guerrero, who was paying Miller $300 to $400 a week for testosterone and HgH. As one investigator told The Palm Beach Post in October, Miller was "the Victor Conte of professional wrestling."

Seeing Corey's elevated testosterone level, Miller advised him to stop using steroids for a while, then put him on a more controlled cycle. The results were unquestionable. In addition to the added bulk -- within a year, Corey's 5' 5" frame swelled from 120 pounds to 160 -- he was breezing through his workouts and improving his times. "Steroids completely change your mind-set," he says. "They turn you from being an athlete into a monster. A monster in the everyday world is not a good thing, but when you are trying to win a 1,000-meter race against five of the best guys in the world, monster is a great mind-set to have."

Patricia Johnston, a hairdresser, had little contact with her son after he left Michigan. As much as she wanted him to stay home, she knew how much skating meant to him. Whether it was being 1,200 miles apart or, as she believes now, the moodiness caused by the drugs, their relationship chilled. "I remember he used to call every now and then and be very angry, and I couldn't figure it out," she says. Still, she would try to watch him skate in big competitions. When she glimpsed her son at a 2002 meet in Watertown, Wis., she gasped. "I couldn't believe how different he was," she recalls. "I said, 'Wow, you really grew.' He was overly muscular."

Corey says that his relationship with his dad would move in lockstep with his results. When he won, he claims that he was rewarded with televisions, PlayStations and even an American Express gold card. On the rare occasions that he lost, he says, his dad wouldn't speak to him. "We had our bouts because I very much wanted a dad and he wanted a business-type relationship," Corey says. "At a young age it's hard to understand why winning all the time matters so much." The father dismisses this complaint: "I'm not some raging animal standing outside throwing stuff against the wall."

Meanwhile, Jim entered a business partnership with Miller to offer laser hair-removal treatments. The two had a falling out in April 2003, however, and Jim set up his own business in Orlando selling anti-aging drugs, including testosterone and human growth hormone. But first he blew the whistle on Miller, alerting the Hillsborough County sheriff's office that Miller's clinic was a front for illegal steroid distribution and that Miller was providing performance-enhancing drugs to a minor -- Corey. Jim neglected to mention his own complicity.

Not long after, Corey, then 14, left Florida to train with a team in High Point, N.C. He moved in with Tracy Patterson, who had gotten involved with in-line skating through her two children. Patterson's husband and 11-year-old son had recently been killed in an auto accident while returning from a meet. "I was lost and to have Corey in the house was a relief," says Patterson. "He's just an incredible kid, a great guy."

Still, Corey continued his steroid and HgH regimen, locking himself in the bathroom to inject the drugs that his father mailed to him. To help get through his workouts, Corey says he was supplementing his performance-enhancing drugs with painkillers, particularly Nubain, procured through a Florida doctor. "When you are jamming yourself with a thousand milligrams of testosterone cypionate, your body is running high, [and] to sleep at night you either have to be extremely exhausted or you are going to have to use something to come down," he says. "It's so easy to get sidetracked and take other things because if you are doing one, why not do them all?"

For all the tension in Corey's life, his skating kept improving. At 15 he was a national champion at 500, 1,000 and 1,500 meters. In July '05, Corey, then 16, competed at the U.S. Indoor Speedskating Championships. His time of 2:26.39 in the 1,500 meters shattered the national record in the sophomore men's category by more than two seconds, remarkable given that most speedskating marks are eclipsed by tenths if not hundredths of a second.

By that time, Corey had already failed his first drug test. A month earlier, at the U.S. National Road Championships in Colorado Springs, his urine sample indicated elevated testosterone levels. He was allowed to keep skating, but when he gave a follow-up sample on Aug. 1, that test also indicated the presence of 19-norandrosterone, revealing yet another banned steroid.

Jim Gahan professed shock to anyone within earshot. He hired a lawyer to protest the timing of the appeals process while asserting that Corey's testosterone level was high because he was tested shortly after a long-distance race. As for the 19-norandrosterone result, he suggested that it was caused by a tainted supplement. Privately, Jim was stunned. He believed the steroids he'd been procuring were undetectable. (His source was Signature Pharmacy, the Orlando compound pharmacy that was the target of a high-profile raid in February '07.) "Corey should never have tested positive," he says.

In April '06 the United States Anti-Doping Agency (USADA) recommended a two-year suspension for Corey and he was ordered to forfeit results dating back to May 2004. Corey's reinstatement was contingent on his getting counseling and receiving a medical evaluation. "This case shows the extent to which drugs have infiltrated youth sports," says USADA chief executive officer Travis Tygart. "It's a grave societal problem. In my view it's just as pernicious as crack cocaine and meth abuse, though some people might think it's more acceptable. It was hard to punish this kid. Yes, he cheated and unfairly beat other competitors, but he was under his father's influence. The kid was a victim."

Acting on Jim Gahan's tip, the Hillsborough County sheriff's office ran surveillance on Miller's office. "We started seeing large males show up in nice cars," says detective Mike Gibson. "They'd stay a short period of time and leave." In October 2003 the clinic was raided. Among the boxes of evidence carted away were Corey's medical file and the log entries that indicated he had visited Miller. The following summer Miller and Pavicic pleaded guilty to conspiracy to distribute steroids to a minor. Pavicic served a six-month sentence in federal prison starting in '05. Miller's sentencing was delayed because he was cooperating in wider steroid investigations and because he had a liver disease. Last fall he received an 18-month sentence for his role in Corey's doping.

When authorities confronted Miller and Pavicic the two men fingered Jim Gahan. At first Corey refused to implicate his father, but by December 2006, after being banned from competition and with the evidence mounting against Jim, Corey decided to cooperate with the investigators. According to Assistant U.S. Attorney Anthony Porcelli, the lead prosecutor in the case, Corey's cooperation was a key element in forcing his father's guilty plea. On Jan. 7 Jim was sentenced for providing steroids to his son. "Even though I kept trying to tell him he didn't do anything -- he just did what he had to and Jim put himself there -- how could he not feel [bad]?" asks Corey's mom. "Because of what he said, 'Wow, now my dad is in prison.' "

During an interview at the Hernando County (Fla.) Jail in November, Jim maintained that Corey's testosterone was abnormally low, providing a bona fide medical rationale for his son's use of performance-enhancing drugs. "If you're a pro athlete and you get caught, you get three strikes," says Jim. "In amateur sports you get caught once, you get laid out for two years. Your career is over. But are kids willing to take that risk to get to that level where the millions of dollars are? They're doing that every day."

But on further reflection, he is contrite: "Am I sorry? Absolutely. One hundred percent. It started out as an innocent thing and blossomed into a nightmare. It wasn't like I was trying to distribute steroids to all the little speedskaters and he and I were making a profit from it. It was just him and me trying to make him the best at what he was doing."

As for Corey, he's back in Grandville, living with his mother. He says it has been more than a year since he has spoken to his father. Now 18 -- and 15 pounds lighter than he was as a 15-year-old -- he works on the loading dock for a department store. His two-year USADA ban has elapsed, but he's unsure whether he'll return to competitive in-line skating. As Corey tries to scrounge together enough money to get his own place, one point still gnaws at him: He firmly believes he could have been a champion without pharmacological enhancement.

Soft-spoken and reserved, Corey wavers among embarrassment, regret and awe when he reflects on his fractured teenage years and his experiment with steroids. "People make it sound like these medications are only performance-enhancing, but they have a huge mental impact as well," he says. "By the time I was done, I was a wreck. When kids get a hold of this stuff, damn...."