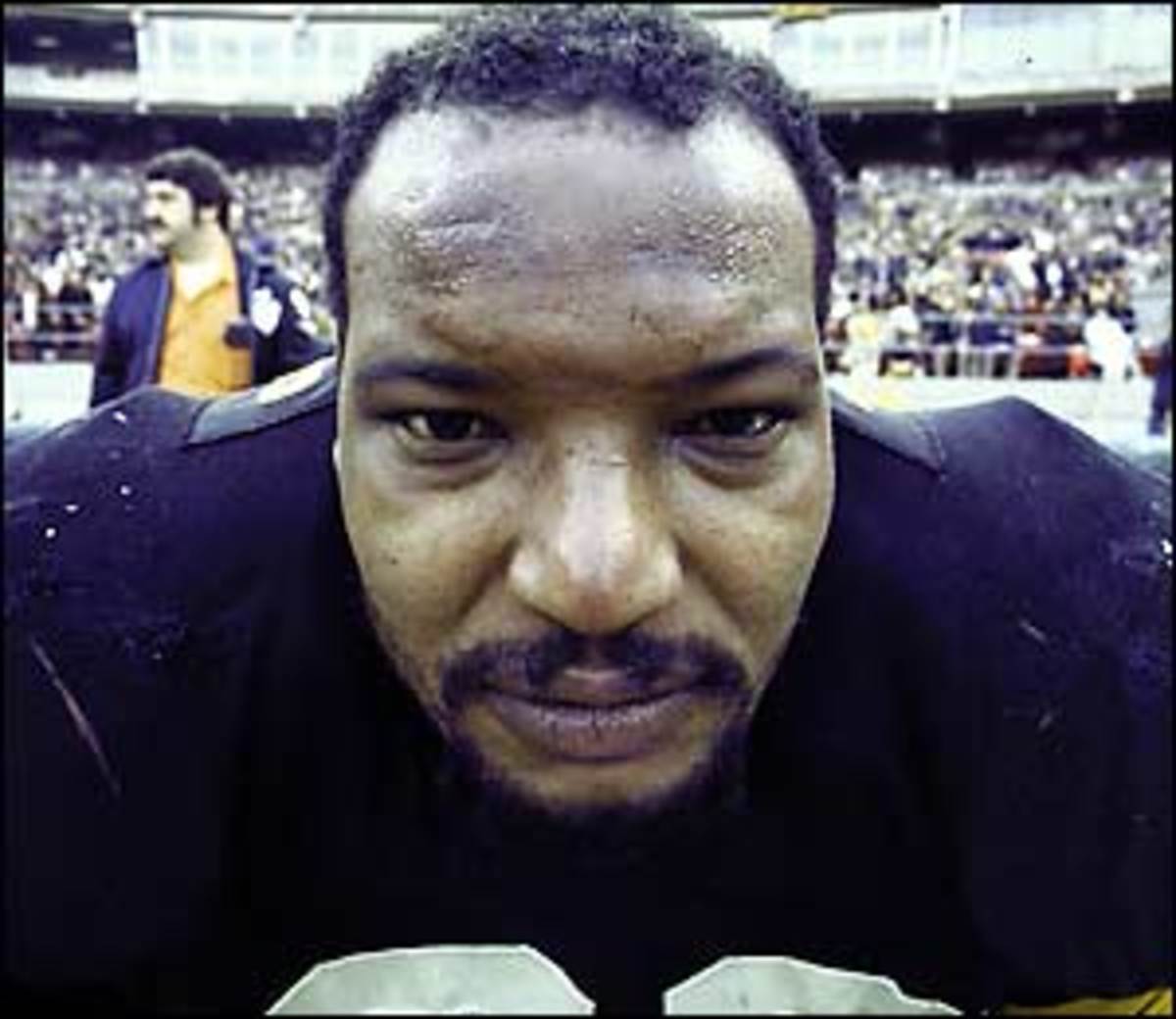

A complicated soul

Once I saw Ernie Holmes pick up a sportswriter by the shirt and hold him, with one hand, against the wall while he lectured the poor guy on the finer points of covering the Steelers. There were people who were scared to death of him, others who didn't want to have anything to do with him, still others who liked him as you would a big, galloping Great Dane puppy.

Count me among the last group ... well, not exactly, because there was always the underlying fear of the unknown with Ernie. You never knew when he would go off.

He died Thursday night at 59 when his car went off the highway and flipped. Many people thought he'd never make it that far, but his former teammates were happy that he seemed to have gotten his life together and was attending Steelers alumni functions.

"He's a reverend now, and he does work with kids," former Pittsburgh linebacker Andy Russell told me a few years ago. "That seems just right for him because he always liked kids."

And, for some reason, Ernie seemed to get a kick out of me, the idea that here I was coming all the way from New York, just to hang out in the Steelers locker room and talk to him. Even after that incident when he pinned the writer to the wall, he turned, saw me, dropped the guy and gave me a big smile. His eyes, which appeared almost shut to begin with, got narrower, the broader his smile got, and now they were just about shut.

"Ah, there he is," he said, "my man from New York."

The world discovered that the 6-foot-3, 280-pound Holmes, who one can safely say was the most feared member of the Steel Curtain defense of the 1970s, was a bit unbalanced when he made headlines by firing his pistol at trucks on the highway. Traffic made him nervous, he explained later. Besides, he said he was careful not to aim at people, just vehicles. When a police helicopter arrived on the scene, he turned his fire skyward.

He was hauled off to prison, and both Chuck Noll the coach, and Dan Rooney, the president, went down to the jail that night. They made a strong case for him. They got his sentence suspended, with a provision that he undergo psychiatric treatment, which he did. When's the last time the coach and team president went down to the jail where one of their players was being held?

Anyway, it gives you a good idea of how important "Fats" Holmes was to their defense. He rejoined the team, and ironically, he was the only Steel Curtain Steeler who never made the Pro Bowl.

"Nobody would line up against him in practice," said Tom Keating, a former Raiders defensive tackle who joined the Steelers for a year in '73, the year before they began their Super Bowl run.

"I got a tremendous kick out of him. I remember one day at practice, a helicopter flew over the field. Ernie stopped and looked up, and this big smile came over his face.

"Looks just like the one I brought down," he said.

Woody Widenhofer, who coached the linebackers, said there were days when Ernie was just as good as Joe Greene. Noll scoffed at the idea that Holmes never earned any kind of All-Pro recognition.

"You want to know how good he was, how tough?" Noll said. "Take a look at the way the guy who had to play against him looks, coming off the field after the game -- if he was able to finish it."

I remember Picture Day before the '76 Super Bowl. Ernie grabbed me and said he wanted to explain what the game meant to him. I took six pages of notes in my 5 x 8 spiral. I didn't understand any of them. I am looking at them right now, and I still don't know what they mean.

"You think I don't care, it's like two iguanas climbing up a tree, which one gets higher, they want to piss on you, I'm not going to let them ..." and on and on, for six pages.

Well, I hope he found some kind of peace toward the end of his life. He was like a big kid. You felt almost protective about him -- but not too closely.