Flashback: Sweet Sound of Santana

Sunday, 11:45 a.m. The place should be as quiet as a church, no? A massive winning streak is on the line today, a man will be knocking on history's door, a man will take the ball and walk out to perform before thousands. He must have silence. He must be left alone. That's baseball's way: No one bothers the starting pitcher. No one talks to him, no one touches him; superstitious teammates don't even look his way.

He's supposed to use this time before a game like a monk, mulling weaknesses and strengths, communing with his arm, staring daggers into his locker until his passion rises and adrenaline builds and he's primed to spring toward the mound like a bucking bronc Wait. Who dialed up the volume?... A ella le gusta la gasolina Dame mas gasolina! Como le encanta la gasolina Dame mas gasolina!

This can't be good. Those players back there, rapping along with Daddy Yankee near the trainer's room, don't they know better? No: Three of them giggle now as music fills the Minnesota Twins' clubhouse, then lean forward to gather in their throats a pitch-perfect imitation of an enraged baseball lifer and shout in English, "Shut the f--- up!"

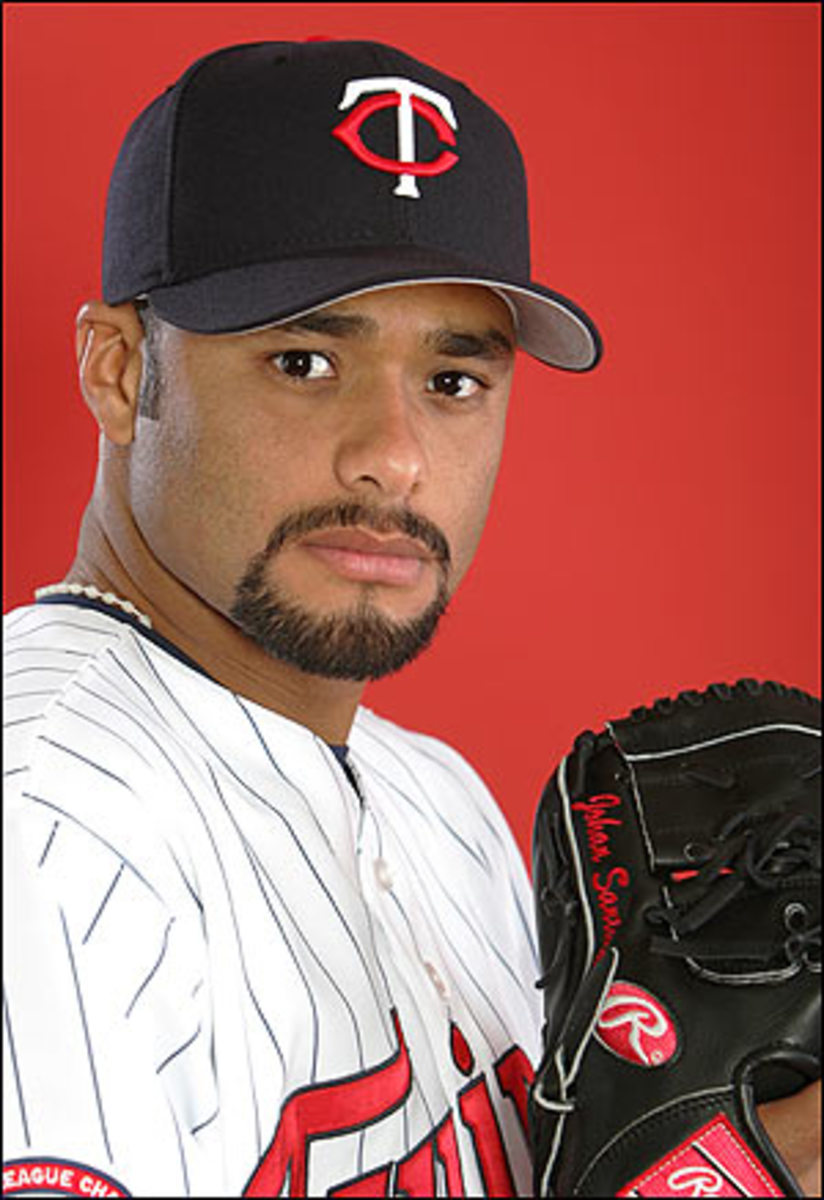

Message: No shutting up around here. But won't the starter Never mind. The three straighten up, laughing louder as the beat pounds the walls and the singer brags, and you can see. One of them is the starter. Johan Santana steps back to his locker, huge grin on his face. He grabs a clear bottle the size of a rummy's fifth, no label, filled halfway with liquid the color of tobacco juice. He sits down, uncorks it, swishes it once under his nose. He pours a bit into his right palm, then rubs the locally produced liniment into his stomach, calves, upper thighs; once he breaks a sweat, it will give his muscles a nice, tight burn. He stands up, and the music nudges him--Duro! (Hard!)--and he dances a few quick steps. Soon he will try to win his 18th straight game, two shy of Roger Clemens's American League record. His teammates jabber at him, and he gives it right back. He sits, and with his right hand massages that precious left arm, shoulder to triceps to elbow. It's the only giveaway: He's pitching soon.

Otherwise, it feels like just another day to the 26-year-old Santana, who won last season's AL Cy Young Award by unanimous vote, who became a national hero in his native Venezuela, who is becoming increasingly known as the best pitcher in the world. When he walks into the clubhouse, he greets everyone with his usual "Happy birthday!" no matter if it's anyone's birthday or not. He's also been known to wish his teammates Merry Christmas in July. The point is to say something guaranteed to bring a smile "because when it's your birthday, you feel like you're getting old--but you also know you're getting a present," Santana says. "This is a game, that's what I think. I try to make people laugh. I see people on the team with a frown on their face, I think they'll go out and play with a frown." Sometimes, on the day he pitches, Santana will roam about the clubhouse, flicking unsuspecting teammates on the head with his finger. "You can't help but love a guy like that," says Twins centerfielder Torii Hunter.

Of course, after pitching like a Hall of Famer for nearly a year, a man could set his teammates' clothes aflame and no one would blink. In his 30 starts from June 9, 2004, through May 11, Santana went 23-3 with a 1.84 ERA, held opponents to a .166 batting average and averaged 11.3 strikeouts per nine innings. With a 5-1 record at week's end, he led the league in strikeouts (67) and strikeouts per nine innings (10.8), while having issued slightly less than a walk per game. He possesses the most bewildering changeup in baseball, has reduced the best hitters alive to relying on guesswork, hasn't lost a game on the road since last May. The Los Angeles Angels will stop his 17-game winning streak this afternoon, but without putting a dent in his aura; Santana will surrender just two hits in eight innings--both solo home runs--lose 2-1, and concede no disappointment afterward. He'll credit his teammates for supporting him throughout the streak, say that he intends to start another one immediately. The next afternoon, as always on his off days, he'll range around centerfield during batting practice, shagging fly balls for fun.

"He wishes he could hit too, because that's how he grew up playing--and he plays the game as if he's still a kid. I wish more players would," says Minnesota manager Ron Gardenhire. "He's the happy birthday guy. That's what he says, and that's what he feels. It's happy birthday every day."

Five days later, to prepare for a start against the Tampa Bay Devil Rays, Santana will engage in his usual routine, which, it should come as no surprise, is hardly routine. He has little use for the scouting reports on opposing hitters, doesn't study tapes, isn't interested in any sentence that begins with the words, "The book on this guy " He's happy to take advice but pitches by feel. He depends mostly on what he reads in opposing batters early, the subtle giveaways--a lean, a take, a glance, a swing--that, as Santana informed a startled Twins pitching coach Rick Anderson late last season, tell him what the batter is thinking. But that's not to say he doesn't prepare.

Indeed, Santana needs quiet time before a start, but he gets it at home, at his town house in suburban Minneapolis. Either the night before or on the morning of the game, he'll check out the lineup of the team he's facing, take in how the hitters have done against him. Then, alone on his bed, he'll pick up his PlayStation Portable, plug in the team he'll soon be pitching against for real, and go to work. His wife, Yasmile, knows to leave Johan alone and keep their two daughters, two-year-old Jasmily and newborn Jasmine, away. His father, Jesus, who stays with Johan when he visits from Venezuela, wouldn't think of approaching him at a time like this. "It's his window into the game," Jesus says. Traditionalists will blanch at the notion--Anderson was speechless when he heard--but who's going to argue with the results? In terms of power and control, only two pitchers in their 20s have ever had a season comparable with Santana's 20-6, 265-strikeout, 54-walk year in 2004: Sandy Koufax in 1965 and Pedro Martinez in '99. Not even the dominant seasons of Ron Guidry ('78) and Dwight Gooden ('85) rate as high. That sound you hear? A rush of pitchers scrambling to their kids' bedrooms to check out the pitching tool they'd dismissed as a toy.

"Believe it or not, sometimes I see things in video games that will come true," Santana says. "Particularly in the last year, they're coming up with some good games, so realistic--the stats are so accurate, and you can go from there. I'm sure a lot of players will agree with what I'm saying. Because it gives you ideas. I see the scouting reports, though I don't go by that, and in these video games you can see what the hitters have, how to approach them. It's pretty cool."

The moment he takes the field, all the looseness disappears. In the Metrodome, "Gasolina" plays over the loudspeakers as he trots to the mound, but Johan Santana doesn't sing or sway now. His face is blank. His pregame antics would make it easy to pigeonhole him as yet another quirky lefthander, or another latino loco, yet on the field Santana cuts about as eccentric a figure as Walter Johnson. His windup contains none of the flamboyance of Luis Tiant, nothing resembling Fernando Valenzuela's eye roll, no signature move like the high kick of Orlando (El Duque) Hernandez. Santana makes but one subtle statement before he delivers: He stands square to the batter, flush left of the rubber, legs apart like a high-noon gunfighter. He does this because he's just six feet tall, 195 pounds, and wants to establish a presence. "You have to let them know: I'm here," he says.

But Santana gets serious, too, because he knows he's representing more than himself. It's not just that he's the latest example of baseball's great Latino boom, or a flash of good news to a nation starved for it. He's standing here as El Gocho, flag-bearer for the Andean region derided for generations by the rest of Venezuela as a rustic backwater. He's standing here, the son of a good ballplayer who wasn't good enough. He's standing here knowing that he came close to not standing here at all.

There's no mistaking the pride in that stance, a declaration of ownership. Once planted, Santana won't let anything--not even the birth of his second daughter--shake him. Just as he was about to warm up for his start against the Kansas City Royals on April 20, Santana got the phone call telling him that Yasmile was in labor. Ten minutes later he got the good news. Yasmile insisted he finish work before visiting, and though he could hear Jasmine yowling in the background, Johan did as he was told: seven innings, 10 strikeouts, no walks in a no-decision. His teammates weren't surprised; if Santana can surrender home runs and pitch as if they never happened, how distracting can a newborn baby be? More than once during the streak Santana suffered an early multirun inning but never panicked. "A lot of guys fall apart then--'Oh, man, I gave up four in the first: What am I going to do?'--and then it usually snowballs," says Minnesota catcher Mike Redmond. "That's what makes him so good: He knows if he pitches the way he can, he'll keep us in the game."

Of course, it's easy to be confident when you've got the repertoire of a legend. "Randy Johnson is good, but Santana is great," says Detroit Tigers designated hitter Rondell White. "He's unhittable. I mean, no one is unhittable, but he's pretty close." Everyone's got an out pitch. But Santana has three that he can locate for strikes anywhere, anytime: a 95-mph fastball, a knee-buckling slider and the changeup that, because it is delivered with exactly the same motion as his fastball but travels 15 mph slower, is breathtaking. His teammates call it the Yo-yo, but Santana prefers the Butterfly because that fluttering, floating beauty leaves hitters looking like cartoon Neanderthals swiping at air. "His stuff is absolutely amazing," says former Twins lefty Frank Viola, the 1988 AL Cy Young winner. "If he's left alone and just goes out there, he will be the most dominant pitcher over the next five or six years. He's got a swagger now."

In his first start after the Angels ended his streak, against a young Tampa Bay team grown cocky after taking three of four from the New York Yankees, Santana produced a performance of mesmerizing efficiency: 92 pitches over nine innings, 29 of his 33 first pitches going for strikes, 16 balls total, no walks, seven strikeouts. None of the Devil Rays escaped looking foolish. "When you get a knock off him, it's pretty much you guessed right," says Aubrey Huff, who tripled off Santana in the first inning. "You don't often see a pitcher who throws 95 and puts it where he wants it--and it actually looks faster. But his best pitch is the changeup, and it's the best in the league."

In the stands in St. Petersburg pockets of fans waved Venezuelan flags. A Venezuelan TV crew has followed Santana for much of this season, and every start is beamed home on national television. But no one is more moved by Johan's success than Jesus. As the momentum of the streak--and the mania in Venezuela--began to build last season, Santana would call home, and his father would come to the phone, try to talk and break down time and again. When Johan asked what was wrong, Jesus said, "You don't know what's going on here. You're so good."

The tears haven't stopped yet. When Jesus, 53, is at home in the 33,000-strong town of Tovar, in the state of Merida, and uncles and cousins come to watch on TV, he will be watching intently one minute and blubbering the next. Jesus spent the month of May in Minneapolis, sitting alone in the stands, "and it happens all the time," he says. "I'll just be overwhelmed. I can't stop, because this is something I dreamed of."

Jesus stops talking, takes off his glasses and wipes his eyes with a worn washcloth. He played amateur ball in Merida, a middle infielder whose impressive range earned him the nickname El Pulpo (the Octopus) and got him a few sniffs from pro teams in Caracas and Maracaibo. But his fame never spilled out of the Andes. He became a repairman for the state power company, working all hours, fixing downed lines, raising five kids poor with his wife, Hilda. He's not bitter about never making it; he watches Johan and recognizes that running style, that agility, those powerful legs. "I look at him, and I see me," Jesus says. "Every time he played, I saw a part of me. A part of me that's better than me."

It wasn't supposed to be this way. Franklin, older than Johan by two years, grew up thick and strong, a catcher in the making, and Jesus expected him to be the athlete. Johan was skinny, book smart, a future engineer, Jesus thought. The two boys would walk to the field for their dad's games, carrying his equipment and holding hands, but Johan was the one who imitated his father's every move. "I always wanted to be like him," Johan says.

The only gloves in the house were Jesus's discards, so Johan grew up throwing righthanded. He played shortstop on his first team at age 10. His next coach recognized his lefthandedness, and Jesus scrounged around until he found a proper glove, old and beat up; season after season, Johan restrung that decomposing thing, until the stink was too much to bear.

In 1994 a Hungarian-born, Venezuelan-based scout named Andres Reiner saw the 15-year-old Santana playing centerfield in the national championships in Guigue, and the kid's athleticism and rocket arm captivated him. Johan loved to dive for catches, loved to throw people out; you could feel it just watching him. But that was the strike year, and along with everyone else the Houston Astros had cut back on spending. Reiner pestered Houston's scouting director for the $ 300 to make the 12-hour drive up to Tovar, got turned down twice, called Houston general manager Bob Watson and was told no again, then called again a week later. Watson caved, giving Reiner the money out of his own pocket just to get him off the phone. "Don't call me again about this kid," Watson told him.

Reiner made the drive. Johan and Franklin were shagging balls off a wall of the house. Reiner knocked on the door and, as Jesus remembers it, said, "I've come to take your son." Reiner described the Astros' Venezuelan academy he ran in Guacara, near Valencia, how bright Johan's future could be. But Jesus's own baseball hopes had left him climbing poles in the rain; he had never pushed his boys to play ball, and now here was Johan, so smart, just a year and a half left of high school. Who knows what he could be with an education? As for Johan, who swept up the dust and flour at his uncles' bakery, Reiner had him at hola. "[My father] didn't get to be a baseball player, and right there I have the chance," Johan says. "I was like, 'Dad, maybe you get this opportunity once in your life; you never know. If I fail, I'll go back to school. Let me take my chance.'"

In January 1995 Johan left for the academy. He wasn't like anyone else there. It had nothing to do with his play. Within months he had been converted to a pitcher and impressed the staff with his leadership, intelligence and work ethic. But none of the great Venezuelan baseball talent had come out of Merida, and certainly not out of Tovar. To the rest of Venezuela, the hills produced soccer players, cyclists and bullfighters, and the people of the Andes were gochos--cowboys, if someone wanted to be kind, but more often the term meant ignorant hillbillies or rednecks. Everyone called Johan "Gocho." Jesus would pray for his son to play well but call Reiner every three days. If it doesn't look as though he's going to make it, he told the scout, send him home. Johan felt miserable the first day, when he saw his dad boarding the bus back to Tovar, and his yearning for home only grew. The boy was too poor and far from Tovar to travel there on weekends, too drained by trying to keep up his studies while playing ball eight hours a day.

After two months Johan, now 16, called his father and said he couldn't take it anymore. He had to either stop studying and focus on baseball, or return to Merida and finish school. Jesus told Johan to make the decision; Johan asked his dad to come get him. When Reiner heard the news, he begged Jesus to wait for two weeks. "And two weeks later Johan called and said, 'Dad, I'm O.K. now. I'm going to stay and play baseball,'" Jesus says. "To this day Johan has never wanted to talk about it. I still don't know what Reiner said to convince him to stay."

When asked, Santana pauses. He is sitting in the Metrodome dugout, owner of a new four-year, $ 40 million contract, the richest in Twins history. He is building a house in Fort Myers, Fla., a sprawling place for the wife he has known since he was nine, for his two daughters, for his parents and siblings to come stay for as long as they want. "It was tough," he says finally. "Mr. Reiner said, 'All you're doing is for them. Nothing is going to make them prouder of you than becoming a professional ballplayer and helping them out. You're going to give your family a better life.' Then I felt stronger."

Somewhere, in those two weeks, Santana had also learned how to lie. Jesus heard his son say he was fine, and believed it, because Johan kept his voice from revealing the gut-twisting pain that he felt. The boy was crying when he spoke and crying when he hung up the phone.

Last season, on the verge of his 20th win, Santana sat down for an interview with a Caracas-based TV crew. The reporter spoke cautiously; he didn't want to offend. "Is it O.K. if I call you Gocho?" he asked. "

O.K.?" Santana answered. "It would be an honor."

In the history of Venezuela, gochos have made their mark as dictators and politicians, but few have ever risen to a level of popular adoration. Santana, the nation's first Cy Young winner, has changed that. He has el gocho embroidered on his glove in red and written on the inside of his jerseys; his friends call him Gocho. "Every time they say 'Gocho' now, the people there feel better," Santana says. "Because the others always thought those bad things, that gochos weren't smart. But it's not that way; gocho doesn't mean people live in cabins and they're shooting people. I'm going to make people proud of being from where I'm from. I'm going to make sure that everywhere I go my people will be represented the way they should be."

When the TV crew returned in May, the same man asked questions. He finished off the interview by screaming live to Venezuela, "Next Friday we will continue with more Gochomania!"

When Santana won the Cy Young in November, the people of Tovar poured into the streets. Santana had flown to Caracas for the announcement, but thinking he was at home and angered by the assumption that he refused to show himself, a crowd surrounded his house and began scaling the walls. Santana's family was inside, and the National Guard was called in. Santana had to go on TV to ask for calm. He came home to a daylong parade through the streets of his youth, past the bullring and the two ball fields, to a church where people crushed in to hear him speak.

Kidnapping those close to the rich and famous has become epidemic in Venezuela, and when he met with president Hugo Chavez in Caracas, Santana asked for protection. Chavez picked up the phone; five bodyguards moved into Santana's house and the house, not far away, where his parents still live. To Santana, who goes nowhere in Venezuela now without security, this is worrisome but comes with the territory. "What can you do?" he says. "It's my country." The flip side is a clout that allows him to donate food for those hit by floods and make ambitious plans for new ball fields, new hopes, in Tovar.

What makes Santana proudest is the fact that major league scouts are now coming to Merida, holding tryouts in a place once thought to be a baseball wasteland. His name has allowed Minnesota to set up an outpost: The Twins have signed three players from Santana's hometown alone. It's appealing, of course, to consider such a cross-cultural exchange -- a Latin superstar set up in snow-white Minneapolis, Vikings fans obsessing over news out of the Andes -- but the fit wasn't always so cozy.

After four years in the Houston organization Santana remained a puzzle: sometimes overpowering, often erratic, a big league talent who couldn't break past A ball. By the time he was 20, he was still, according to then Astros general manager Gerry Hunsicker, just "a solid prospect," behind the more advanced likes of righthander Freddy Garcia. Houston left him unprotected for the 1999 Rule V draft. "Am I surprised at what he has turned out to be? Yeah," Hunsicker says. "But this is a business of numbers. In hindsight, it was a poor decision." The Twins, bolstered by good reports on Santana out of the minors, had the first pick, but engineered a predraft deal in which the Florida Marlins--who had the second selection and were hot after Jared Camp, a Rule V--eligible pitcher in the Cleveland Indians' system--would draft Santana and then trade him to the Twins for Camp, throwing in $ 50,000 to cover the cost of Minnesota's selection.

So the Twins got him for free, and Santana got his big break. As a Rule V player Santana had to stay on Minnesota's major league roster for the entire 2000 season, during which he struggled both out of the bullpen (2-0, 5.34 ERA in 25 appearances) and as a starter (0-3, 9.82 in five tries). But the Twins liked his professionalism and maturity, and Santana stayed in the mix until a muscle tear in his left elbow slowed him up midway through 2001. He tried to stay patient. He had great stuff but couldn't control it. "I used to be a thrower," Santana says. "Now I can hit my spots, recognize better what the hitters are doing. Before, I was just ... hoping."

He started the '02 season at Triple A Edmonton, working almost exclusively on perfecting his changeup with pitching coach Bobby Cuellar, and everything began to click: 75 strikeouts in 482/3 innings, a 3.14 ERA. But when the Twins brought him up in midseason, Santana was still so wild that Anderson would plant the catcher in the middle of the plate and hope for the best. Certain by now that he should be a starter, Santana kept working and, despite shuttling from starter to reliever, led the club in strikeouts with 137. He arrived for spring training in 2003 expecting his reward. Gardenhire and Anderson told him that he would be in the rotation. Then, on March 13, his 24th birthday, the happy birthday guy got the news: Minnesota had reached agreement with 38-year-old starter Kenny Rogers. Santana was headed back to the bullpen.

He felt betrayed. He stormed into Gardenhire's office. Treat me like this? Trade me. Santana left steaming. "I wasn't going to let it ruin my birthday," he says. "I went home to see my wife and daughter. My daughter means a lot to me. To go home and see her beautiful face and spend time with her, you forget about everything else. Then I get here, and the nightmare starts again."

Within days, though, Santana turned bitterness into power. He went back to the bullpen with only one thought: shove it down their throats. He didn't allow a run in his first seven appearances, had a 2.41 ERA at the end of June. Back in the rotation on July 11 Santana emerged as the Twins' ace and finished with a 12-3 record and a 3.07 ERA. Last year, after a slow start caused by off-season elbow surgery, Santana struggled, and Minnesota lagged a half game behind the Chicago White Sox in the AL Central. Then he began to air out his motion, trust his arm, and the golden year ensued: 13-0 with a 1.21 ERA after the All-Star break. Santana became the first pitcher to win that many games after the break without a loss. The Twins took the division by nine games.

"I figured he was trying to prove us wrong, and I figured once he got in the rotation and did well, it would come back and I'd hear it: 'I could've been doing this a long time ago,'" Gardenhire says. "And I have heard that. You know what? I agree with him. Maybe we were stupid."

Who knows? Maybe Santana needed that humiliating slap. Maybe, without that final motivation, he would've been content to be good instead of great. Santana is not arrogant; it's not the gocho way. But his pride is as obvious as the beard on his face: After a strikeout, he puffs out his chest and sets his glove on his right hip and turns on his heel, like a matador giving the bull his back. Maybe the Twins were smarter than they knew. When, as in that 7-1 win over Tampa Bay, Santana is on, it's impossible not to feel that you're watching that rare thing: the moment when youth, experience, talent and fire mesh, and excellence looks absurdly easy.

With two out and Santana closing in on just the second complete game of his career, Alex Gonzalez chopped a ball high to the pitcher's left, demanding a series of athletic acts that no video game could prepare him for, a series that, if not executed perfectly, could result only in error or injury. Santana turned his back to the plate, took two broad steps and jumped, catching the ball over his shoulder like Willie Mays as Gonzalez flew down the line. Santana landed on his left foot and began to fall toward third and, while tottering, gathered the ball and whipped it sidearm to first: a strike. Gonzalez out by five feet. Santana put his head down and went straight for the dugout. He didn't need to celebrate. He knew. The game was his.

From the May 23, 2005 issue ofSports Illustrated.