The Education of Chris Long

As the ground shook and the trees swayed, Diane and Howie Long scooped the three boys out of their beds, grabbed armfuls of blankets and pillows, and made their way to the front door. The boys knew the drill by heart. Every day Howie would park his Chevy Suburban in the same spot in the driveway, just beyond the reach of the tallest trees. If an earthquake rattled Los Angeles, it meant they were all spending the night in the Suburban -- two adults, three kids and two dogs. "You had to think about aftershocks," Howie said.

The Longs lived in Los Angeles for 12 years, while Howie starred at defensive end for the Raiders and Diane worked as a corporate lawyer. But shortly after the Northridge earthquake in January 1994 -- 6.7 on the Richter scale -- they decided they'd spent too many sleepless nights in their Suburban. So they embarked on a national search for a new home. Possible destinations included Oregon, Cape Cod and the Raleigh-Durham area of North Carolina.

They settled in Charlottesville, Va., a genteel college town of red bricks, white columns and trees that generally stay upright. For the boys -- Chris, Kyle and Howie Jr. -- Charlottesville was a haven and a playground. They went fishing in Sugar Hollow and inner-tubing in the James River. They attended school four miles from home, at St. Anne's-Belfield. And when it came time for the oldest, Chris, to choose a college, all he had to do was cross Ivy Road from St. Anne's-Belfield to reach the University of Virginia.

It all looked so easy. He had the Hall of Fame father, the big house, the summers in Montana, the weekends in L.A. with Terry Bradshaw and Jimmy Johnson at the Fox Sports studio. But when Chris accepted a football scholarship to Virginia and e-mailed another recruit, linebacker Clint Sintim, to introduce himself, Sintim did not respond. "I didn't really care for him," said Sintim, who had yet to meet Long. "I thought he was just a rich kid with a famous dad."

Then Sintim got to Virginia and saw how Long approached game days. Chris had eye black smeared across his cheeks and D-Block blasting out of his headphones. He stalked around the locker room, screaming at himself and his teammates, explaining in vivid detail how he was going to annihilate the man in front of him and how his teammates would annihilate the men in front of them. "Who's going to ride with me?" he hollered. "Who's going to ride with me?" This did not sound like some spoiled rich kid. It sounded like Ray Lewis.

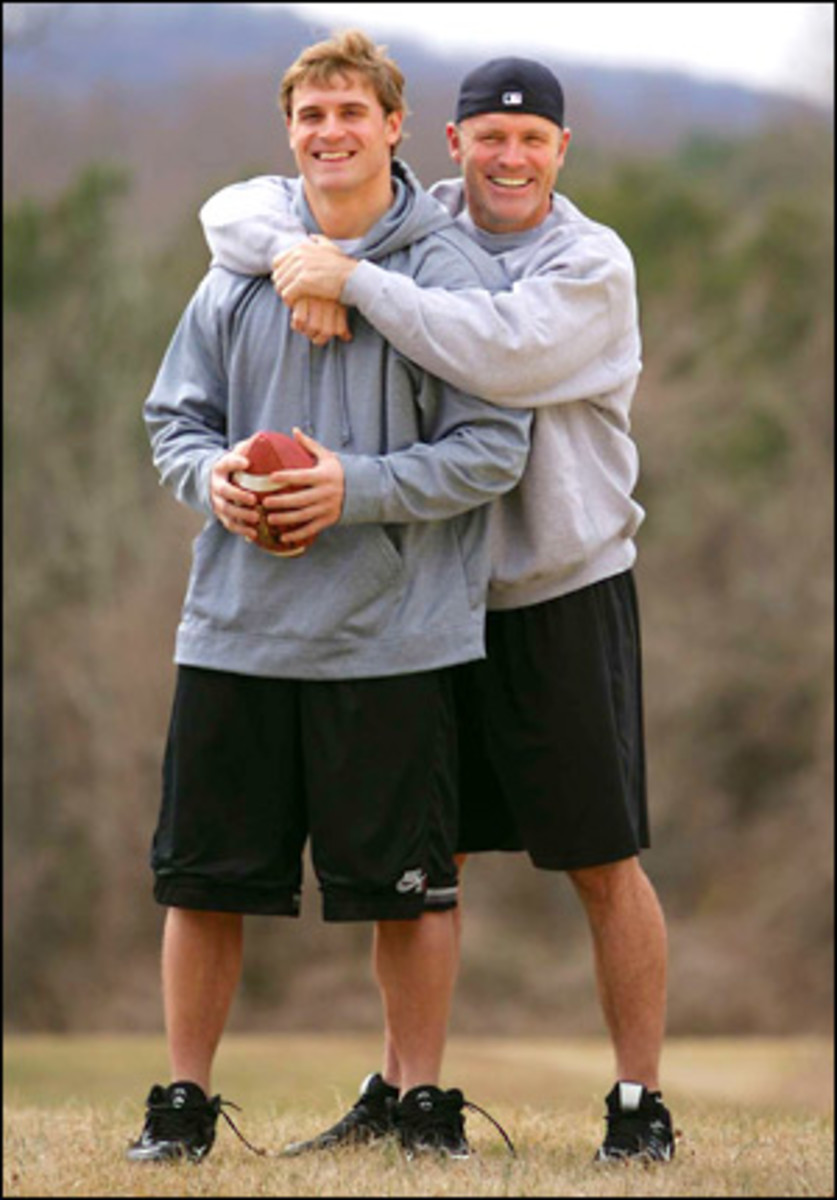

Football players, especially pass rushers, are often fueled by hardships they faced early in their lives. This is true for Lewis, for Shawne Merriman and for Howie Long. Chris is the opposite. He is fueled by the lack of hardships he faced, by the perception that his advantages somehow made him soft. The fuel is different, but potent nonetheless. After four years spent pile-driving quarterbacks as a defensive end at Virginia, Chris is projected as the possible No. 1 pick in the NFL draft on April 26. And Sintim, of all people, is one of his roommates and closest friends. The Longs refer to him as their fourth son.

"I was obviously wrong about Chris," said Sintim, who'll be senior in 2008. (He redshirted as a freshman.) "He is not soft or spoiled at all."

Ever since Chris arrived in Charlottesville, at age nine, he has been trying to make that point. In Los Angeles he did not play football, did not watch football and picked daisies in the outfield during his Little League games. He spent his free time writing science-fiction and adventure stories. His parents thought maybe he'd become an architect. After the family moved, Chris asked to try out for a youth football team called the Eagles, mainly because he liked their green uniforms. Howie told Diane the boy would get hurt in the first practice and give up. Even after Chris survived that first day, Howie told the coach, Mark Sanford, "I'm not sure he'll stick with this game."

As a ninth-grader Chris went out for the football team at St. Anne's-Belfield, a private K-to-12 school with an enrollment of about 840. But when he tried to run at his first practice, he looked as though he might trip over his size-13 cleats. Coach John Blake told him to get on the defensive line and drop into a stance. Chris bent down -- back perfectly straight, butt high in the air, free hand tucked behind his leg. Chris's eyes even bugged out. "Oh, my God," Blake said. "That's Howie Long." It was the first of a thousand comparisons.

Chris befriended a school custodian, McKinley Breckenridge, who let him into the weight room when he wanted to lift after 10 p.m. His devotion to football grew at the same rate as his body. Before every game Blake would gather the team in the locker room and read his favorite poem, The Man in the Glass. Chris knew it so well that he'd recite it aloud, right along with Blake.

Three days a week Howie worked with the St. Anne's-Belfield football team as a volunteer assistant coach. After Chris committed to Virginia in the fall of his junior year -- he made no other visits -- opposing fans continued to serenade him with chants of "Howie, Howie." During a high school baseball game, as Chris took his lead off first, the first baseman told him, "I can't wait until you get to Virginia and get your ass kicked every day."

At the beginning the first baseman got his wish. As a freshman Chris had to practice against Cavaliers junior D'Brickashaw Ferguson, one of the best offensive tackles in the country. Lying on his back every afternoon, with Ferguson standing over him blocking out the sun, Chris thought about that smart-mouthed first baseman. He too wondered if he deserved everything he had. "It makes you question if you belong, if you're any good," Chris says.

Howie was mostly out of sight, even though Chris and Virginia coach Al Groh pleaded with him to visit practice. He only attended open practices and stopped going to road games because the television cameras kept finding him. Even at Scott Stadium he wore a baseball cap and wandered the concourse like a nervous nomad, never wanting to draw the spotlight from his son. By Saturday night he was on his plane for Los Angeles so he could be at the Fox studio in time for the Sunday-morning NFL pregame show.

But on Monday nights, when no cameras were rolling, Chris went home to watch game tape with his dad. Sometimes they would move the coffee table out of the way and line up across from each other in the family room, Howie showing Chris how to rip through a tackle's hands and charge at one side of his body.

"You always tell young guys to learn offensive formations, and they say, 'Yeah, yeah, yeah,' " says Mike London, Long's defensive coordinator at Virginia and now the head coach at Richmond. "Chris could read formations and know what blocks to expect from each one. That's what Howie instilled in him. That's the work they did at home."

The Long house is decorated with sporting goods. In the foyer is a glass bowl full of used baseballs. On the couch are chewed-up tennis balls. Kyle, a senior at St. Anne's-Belfield, walks around with a wooden baseball bat. Howie Jr., an 11th-grader, dumps a lacrosse helmet on the kitchen counter. It's hard to pick the best athlete in the family. At 6' 7" and 285 pounds, Kyle was recruited by dozens of the best college football teams in the country. But he's also a lefthanded pitcher-first baseman with a 96-mph fastball and a .507 batting average. He has committed to play baseball at Florida State. Howie Jr. has committed to play lacrosse at Virginia. If all goes well, the Longs will have two first-round draft picks in the next three months -- Chris in football, Kyle in baseball. "That would be pretty cool," Kyle says.

Howie's childhood could not have been more different than the one he has provided for his sons. He grew up in the gritty Charlestown section of Boston, forsaken by his parents when they divorced and raised by his uncles. By the time he was seven he was fighting in the streets. In high school he missed 45 consecutive days of class. Three years ago Howie took the boys to Charlestown, to show them the dark corners and back alleys of his youth. The message of the visit was obvious. "He wanted to give us everything he didn't have," Chris says.

While Howie Jr. is the wisecracker and Kyle the charmer, Chris is more like his amped-up dad. He is 6' 4", 275, with blond curls and a square jaw. If he sits still for more than a few minutes, his legs start to shake in nervous anticipation. When he's happy and relaxed, Chris surfs opposing team's message boards, mining them for inflammatory posts that will rile him up again. "I can't be idle," he says. "I'm a restless soul."

Amid all the youthful energy in this house is 86-year-old Frank Addonizio, Diane's father, who has suffered from lymphoma for five years. He lives in a cottage on the Longs' 65-acre property, down a path from the main house. There he puts together a scrapbook for Chris, the way he once did for Howie. Every few days Chris stops by the cottage. Frank tells him about his poker games at the senior center. "I just want to see how these three kids end up," Frank says. "That's what keeps me going. That's the carrot I'm trying to catch."

At this time a year ago Frank had no idea that his eldest grandson would be a highly rated NFL prospect. Chris was second-team All-ACC playing in Virginia's 3-4 defense. He occupied a lot of blockers without making a ton of plays. But last summer ESPN's Todd McShay, the director of college football scouting for Scouts Inc., declared on the air that Long would be the best senior in the country. Colleagues asked McShay, "Are you serious?"

Then Long made an interception against North Carolina, blocked a field goal against Middle Tennessee and had a safety against Maryland, each play setting up a Virginia victory. He finished the season with 14 sacks and 23 hurries and became the first Virginia player to have his jersey retired before his last game. Tiki Barber had to wait 11 years for the same honor; his Cavaliers jersey was retired on the same day as Long's.

At some point the comparisons to Howie began to fade. Even though they both played defensive end in a 3-4, Chris is clearly quicker with his feet and his hands, so much so that he's capable of becoming an outside linebacker in the NFL. Steve Rosner, who represents Howie and used to represent Lawrence Taylor, turned to Howie during a game at Virginia last fall and told him, "Chris is as close to Lawrence Taylor as anybody I've ever seen."

In January, Howie walked into a meeting with NFL commissioner Roger Goodell and was greeted by the league's executive vice president, Joe Browne. "It's great to finally meet Chris Long's father," Browne said.

The Miami Dolphins, who have the first pick in the draft, will have all the intelligence they need on Chris. Their new executive vice president is Bill Parcells, under whom Groh worked as an assistant during Parcells's stints with the New York Giants, New England Patriots and New York Jets. Groh has told Parcells, "He's your kind of player."

The evidence is in the anecdotes. After Chris was honored as the ACC Defensive Player of the Year in December, he flew home from the awards banquet with Virginia sports information director Jim Daves. During a layover in Philadelphia they learned that the Cavaliers would play Texas Tech in the Gator Bowl. Chris grabbed Daves's laptop computer, called up the Texas Tech website and clicked on the bio of left tackle Rylan Reed. Daves asked him why. "Because he's got my lunch money," Chris responded.

Virginia lost to Texas Tech 31-28; but even before the game began, Long had impressed Reed. "When you watch film, it can be kind of boring," says Reed. "But it was actually fun watching Chris Long. The guy won't quit. He thinks he's going to make every play. He will not accept getting beat. It was really an honor to be on the field with him."

There are other candidates to go No. 1 in the draft this year, including Boston College quarterback Matt Ryan and Michigan tackle Jake Long. Chris met Jake (the two are not related) at an all-star camp and keeps his number 77 Michigan jersey tacked to a wall in his apartment, alongside posters of Allen Iverson, Muhammad Ali and Ray Lewis. "I don't know of a player in this draft who has no negatives," says Gil Brandt, draft analyst for NFL.com and former vice president of player personnel for the Dallas Cowboys. "Except Chris Long."

While many prospects prepare for the draft at training centers in Miami, Arizona and Southern California, Long is shuttling between New Jersey, where Rosner is handling his business affairs, and Charlottesville, where he shares a duplex with nine teammates. The floor is strewn with laundry and Entenmann's boxes. He's still a college kid, even though he's no longer enrolled.

Chris's tour of Charlottesville is nothing like his father's tour of Charlestown. He passes bookstores, cafés and record shops. He pauses at Littlejohn's, a deli that serves a sandwich named after former Cavaliers basketball star Ralph Sampson. The owner, Chris Strong, says he's planning a new foot-long hot dog in honor of Chris.

The tour ends at Wayside, a chicken shack just off campus with the slogan, "This chicken 'clucks' for you." Wayside is the kind of place where you order at the counter and ask for extra napkins. After returning from the NFL combine in Indianapolis last week, Chris figured he could indulge in a little grease. Wayside was his first stop. He ordered a box of 16 fried drumsticks and ate about 10 of them.

Every few minutes, cooks and cashiers popped out of the kitchen to say hello and ask Chris where he's going in the draft. He smiled and shrugged, as uncertain as everyone else. It could be the Dolphins, St. Louis Rams, Atlanta Falcons or even his father's Oakland Raiders.

No matter where he's headed, the ground will never be as stable as it is right here.