When Worlds Collided

From Rome 1960: The Olympics That Changed the World, by David Maraniss. © 2008 by David Maraniss. To be published by Simon & Schuster.

More than half of the 305 athletes who would represent the U.S. in the Rome Olympics were in New York City on Aug. 15, 1960, for a send-off rally at City Hall. Besides Mayor Robert Wagner, a military color guard and a stairwell full of politicians, there was retired five-star general Omar Bradley, stirring echoes of a time when Americans had swept through Europe as liberators. World War II was a mere 15 years gone, and its aftereffects were still evident in Italy. Yet the conflict seemed as remote as the Roman Empire to many of the U.S. athletes, whose lives had been shaped by a relentlessly forward-looking postwar culture.

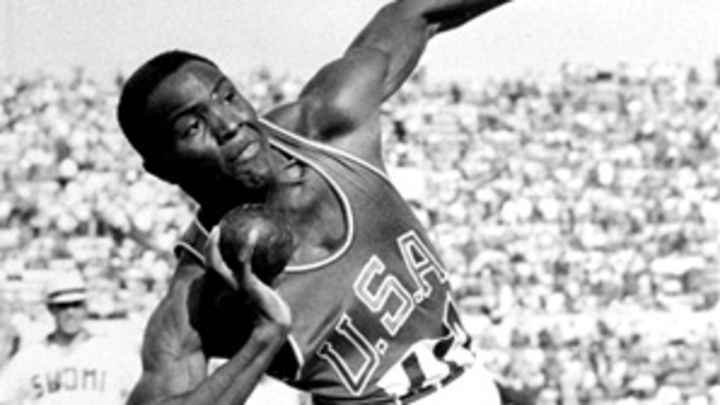

Rafer Johnson was chosen to speak for his teammates. "It is the goal of each of us to win a gold medal," he told the crowd. "Naturally, that's not possible for all.

But we hope to do the best job possible of representing our country." Simple words, even prosaic, but with Johnson the whole often was greater than the sum of its parts. He sounded self-assured yet humble. No one looked sharper in the U.S. Olympic team's travel dress uniform: olive-green sport coat, slacks, beige knit shirt. Johnson flawlessly called out the names of the dozens of teammates who stood at his side. He had a firm grasp of the occasion, and team officials took notice. His performance in New York, along with his stature as the gold medal favorite in the decathlon, convinced the officials that Johnson should be the U.S. captain in Rome and the first black athlete to carry the U.S. flag at an Olympic opening ceremonies. There could be no more valuable figure in the propaganda war with the Soviet Union, which wasted no opportunity to denounce the racial inequities of the U.S.

Beneath his composed exterior, however, the 25-year-old Johnson was a jumble of emotions: joy, pride, anticipation, gratitude, determination and anger. He refused to be manipulated, yet he could not escape the burden of other people's expectations. He was aware, he later said, of the irony of representing a nation that treated people of his color as second-class citizens, but he also felt he could advance their cause most effectively by doing what he did best, which was to excel at his sport and comport himself with dignity.

That night, after an informal reception at the Waldorf-Astoria, three busloads of athletes set out for Idlewild Airport and the flight across the Atlantic. One plane, a prop DC-7C, carried the cyclists and weightlifters, some of whom spent the night drinking and gambling. Another flight took the heavyweight crew and the women's track team, which included eight members of the Tigerbelles, the runners of little Tennessee State University. The white rowers and the black track stars spent the night playing whist and pinochle together. The fleetest of the Tigerbelles was Wilma Rudolph, known to her friends as Skeeter, a nickname her high school basketball coach had given her for the way she buzzed around the court. The 20-year-old sprinter, whose track career had been interrupted by pregnancy and childbirth, had left behind her two-year-old daughter, Yolanda, with her parents in Clarksville, Tenn.

A third plane carried the Olympic boxing team, including an obstreperous 18-year-old light heavyweight from Louisville named Cassius Marcellus Clay. In Manhattan that week he had told Newsweek sports editor Dick Schaap that he would win a gold medal and be "the greatest of all time," but his fear of flying was so strong that it took all his teammates to persuade him to board the plane. If God wanted us to fly, he repeated over and over again, He would give us wings. According to light middleweight Wilbert McClure, Clay spent the night "talking about who would win gold medals and dada-dada-dada." Not for the last time, the man who would become Muhammad Ali was running his mouth and boasting to overcome his own fears.

In the annals of the modern Olympics, other years have drawn more notice, but none offers a richer palette of character, drama and meaning than 1960. The Rome Games, during 18 days in late August and early September, shimmered with performances that remain among the most golden in athletic history, from the marathon triumph of Ethiopia's barefoot Abebe Bikila to the domination of the U.S. basketball team led by future NBA stars Jerry West, Oscar Robertson and Jerry Lucas. But beyond that the forces of change were at work everywhere. In sports, culture and politics, interwoven as never before, an old order was dying and a new one being born. The world as we know it today, with all its promise and trouble, was coming into view.

These Summer Olympics were staged during one of the hottest periods of the cold war. Just before the Games began, Francis Gary Powers, the U.S. U-2 pilot whose plane had been shot down over the U.S.S.R. on May 1, was convicted by a Moscow court on espionage charges. A few days before the closing ceremonies, Soviet premier Nikita Khrushchev set sail for New York City, where he would pound his fist and rail against the West at United Nations headquarters. In between, while athletes from East and West Germany competed as a combined team in Rome -- a united facade that had been ordered by Avery Brundage, the International Olympic Committee president -- officials in East Berlin closed their border temporarily, laying the first metaphorical bricks for what, months later, would become the all-too-literal Berlin Wall. For the first time the Chinese team at the Olympics represented the Communist mainland, and Taiwanese athletes such as the decathlete C.K. Yang were forced to compete for their island alone.

Television, money and drugs were altering everything they touched. Old-boy notions of amateurism, created by and for upper-class sportsmen, crumbled in the Eternal City and would never be taken so seriously again. Rome brought the first commercially broadcast Summer Games, foreshadowing today's multibillion-dollar Olympic television contracts; the first Olympic doping scandal, with the death from heatstroke of a Danish cyclist, Knud Enemark Jensen, after allegedly ingesting amphetamines and perhaps a drug to boost blood circulation; the first rumors of anabolic steroid use, involving Eastern bloc weightlifters; and the first runner paid to wear a brand of track shoes (Puma) in Olympic competition, 100-meter gold medalist Armin Hary of Germany.

New nations were being heard from, notably ones in East Africa, whose distance runners emerged at the 1960 Games. And in Rome, as throughout the world, there was mounting pressure to provide equal rights for blacks and for women after generations of discrimination, which was reflected in the swell of cheers for the U.S. delegation as it marched into the Stadio Olimpico during the opening ceremonies with Johnson bearing the flag. Johnson's movements were rhythmic, precise. Keep in step, he told himself. Don't drop the flag. He cradled it, one observer thought, like a baby.

Among the dignitaries at the opening ceremonies was Air Force general Lauris Norstad, supreme commander of NATO forces in Europe, a quintessential cold warrior who had developed the air defenses for Western Europe against possible Soviet attack. "What an impressive experience!" Norstad wrote to an associate about the sight of the U.S. delegation striding onto the track. "By far the greatest and warmest applause was for the American contingent. Our group flag bearer and leader was Rafer Johnson, and he looked magnificent. I discreetly inquired from people of several nationalities about their reaction to this colored boy being in the lead, thinking that there might be some feeling that this was arranged for political purposes, but I found that the case was quite the contrary. It was generally believed that he had been elected by his teammates, but that even if he had been appointed by officials, it was in recognition of the fact that he was a very fine man and perhaps the world's outstanding athlete."

Johnson was not concerned about why he was chosen. He knew that he had won the respect of his athletic peers, and he thought he could make no stronger statement in support of civil rights than to be captain of the U.S. delegation at a time when it was still acceptable for a white official to refer to him as a "colored boy."

On Sept. 2 Wilma Rudolph won the gold medal in the women's 100-meter dash, enthralling not only fans inside the Stadio Olimpico but also millions of Americans back home, who viewed the event hours later on CBS. With that one race, Rudolph shot from relative obscurity to international stardom. It was not just the way she ran -- so lithe and flowing -- but the combination of her speed, her biography and her winning personality. Long before it was commonplace for the media to build Olympic coverage around personalities, attention was suddenly lavished on the Wilma Rudolph story: how she had overcome childhood polio, teenage pregnancy and unwed motherhood to triumph on the Olympic stage.

Wherever Rudolph went on the streets of Rome, adoring fans pushed forward to be photographed with la Gazzella Nera -- the Black Gazelle. For a self-described lazybones, the hoopla should have been too much. Rudolph had lost 10 pounds in the searing Roman heat, and one of her ankles was tender from a training mishap in which she stepped into a sprinkler hole. Then there was the distraction of having watched her boyfriend, Ray Norton, who had entered the Olympics billed as the next Jesse Owens, finish last in the finals of the men's sprints, sending reporters to the thesaurus in search of synonyms for Armageddon. But worrying was not Rudolph's style. She had been so relaxed before her 100-meter final that she'd taken a nap in the holding room.

Rudolph became a symbol to her teammates and to all women in sports. Anne Warner, one of the so-called Sweethearts from the Santa Clara Swim Club, which combined to win six gold medals in Rome, said Rudolph "was really a hero for a lot of us." Warner remembered facing her own polio scare before she entered kindergarten, when there was a widespread belief that the disease spread in swimming pools. "I think when I was five I went swimming at a local pool and got a high fever, which was a sinus infection, and my mother rushed me to the doctor. My pediatrician's wife had been taken to the hospital that day to an iron lung from which she never came out. The fact that Wilma Rudolph had become such a magnificent runner was remarkable."

Just as Rudolph had overcome the odds, so had her coach and teammates from Tennessee State, the historically African-American school in north Nashville. Women's track and field was a forlorn outpost on the frontier of U.S. sports in 1960. Only a few colleges, mostly black schools in the South, had track programs for women. There were no scholarships. When Ed Temple was named head coach at Tennessee State in 1953, it was because nobody else wanted the job. His first budget was under $1,000. Ten years later, even after Temple had placed six runners on the 1956 U.S. Olympic team and seven on the '60 squad, the Tennessee State athletic department would not give him an office. He shared a cubbyhole with his wife, the campus postmistress, and borrowed her desk.

For years, while competing in the South, Temple's team had traveled not by bus but in two station wagons, one driven by him, the other by the sports information director, Earl Clanton, who had coined the nickname Tigerbelles, a felicitous melding of tiger and Southern belle. Their road trips ventured deep into Jim Crow territory, and it was best if they filled the gas tanks beforehand; getting service at filling stations along the way couldn't be guaranteed. At some point there would be a shout from the back of a wagon: Time to "hit the fields," meaning pull over so the girls, not allowed to use rest rooms reserved for whites, could scramble into the darkness for relief. Near the end of the trip, an order would come from the front: Get your stuff together. This meant rollers off, lipstick on, hair brushed and clothing straightened. "I want foxes, not oxes," Coach Temple told his runners. They perfected the art of emerging from the least comfortable rides looking as fresh as a gospel choir, for which they were often mistaken.

In Rome the Tigerbelles earned the recognition they were denied back home, led by the wondrous Wilma. As Rudolph and five other competitors stepped onto the track on the afternoon of Sept. 5 for the 200-meter final, Temple, who was also the U.S. women's track coach, had a good feeling. The 5' 11" Rudolph, he would say later, "could just run the curve so well, plus when she hit the straightaway she could open up with her long legs and her fluid stride." Before a qualifying heat she had been so confident that she asked Temple if it would be O.K. for her "to just loaf" if she was well in front. Give it your all for 150 meters, the coach said, then look around, and if you have a good lead, go ahead and coast. That is exactly what Rudolph did, but she coasted to an Olympic record of 23.2 seconds.

In the final she not only faced a wet, slow track and a swirling wind but was also handicapped by being slotted in the far inside lane, where the curve is tighter and more difficult for a long-limbed runner to negotiate. At the gun Rudolph was slow out of the blocks, but on the curve she surged past the field, and down the straightaway she lengthened her lead with every stride. In the stands even the German fans, who had been chanting in unison for their blonde countrywoman Jutta Heine in lane 3, joined in the roar for the American.

It was an unspectacular time, 24.0 seconds, but the victory was historic. From a crowded little red house in Clarksville, from a family of 22 kids, from a childhood of illness and leg braces, from a small black college, from a country where she could be hailed as a heroine yet denied lunch at a department-store counter, Wilma Rudolph had swept the sprints in Rome, winning the second of three gold medals that would guarantee her Olympic immortality.

The joke was that an hour after that victory she ran harder than she had on the track. As she and teammates Lucinda Williams, Barbara Jones and Martha Hudson approached the Olympic Village, a mob of fans spotted Rudolph and started toward her. But she had done enough for one day, and an electrical storm was about to hit Rome, so she and her fellow Tigerbelles just took off, sprinting away toward their dorm. They easily outdistanced their pursuers, a Nashville columnist noted, "including the rain, which they beat by 15 yards."

When darkness fell that night, the action moved across Rome to the Palazzo dello Sport for the boxing finals. The new arena was packed with a standing-room-only crowd of more than 18,000 raucous fans. The dominant Italian contingent was vociferous, on edge, ready at any time to burst into song ("as if every man in the audience was a Caruso," the British writer Neil Allen noted in his diary) or to unleash harsh whistles. The home team had six men going for gold out of 10 weight classes. The U.S. had three.

In the light middleweight match, after two Italians had lost and one had won, Wilbert McClure of the U.S. outpointed Italy's Carmelo Bossi in a decision that the home fans found hard to dispute even as they intensely disliked it. That was the situation when middleweight Eddie Crook, a U.S. Army sergeant based at Fort Campbell, Ky., entered the ring to face Poland's Tadeusz Walasek. Yanks in the stands sensed anti-American sentiment bubbling up in the crowd. To Pete Newell, the U.S. basketball coach, it seemed rooted in ideology. He believed there were many Italian Communists in the arena. Whether it was politics or merely boxing's combustible mix of mob psychology and controlled violence, there was no doubt as to the hostility toward Crook in the stands.

Crook boxed deliberately, using his left to keep Walasek away while dodging the Pole's occasional errant swings. Most boxing writers thought Crook outboxed Walasek and were not surprised when he was declared the winner. But the Italian crowd jeered the decision. When Crook took the podium to accept his medal, he looked around in astonishment as the audience whistled and hissed.

The protest persisted as the U.S. flag rose to the rafters. American fans stood to sing the national anthem with uncommon vigor. Washington Post writer Shirley Povich focused on the loudest singer of them all: "A visitor in Rome named Bing Crosby . . . unloaded with a fierce Ethel Merman bust-down-the-roof vigor that could get him thrown out of the crooners' union."

Cassius Clay heard the commotion from his dressing room. He was next up for the U.S., coming out to face another Pole, Zbigniew Pietrzykowski, for the light heavyweight title. The booing strengthened Clay's resolve as he made his way to the ring. Although only 18, Clay did not lack experience. By the time he reached Rome, he had fought in 128 amateur bouts. Early in his career he exhibited an urgency to be in the spotlight that made him at once charming and irritating. Nikos Spanakos, his teammate on the Olympic squad, remembered an incident when he and his brother Pete, another boxer, were getting off a plane with Clay after a Golden Gloves meet in Chicago. "Photographers came out to take our pictures, and Cassius actually pushed us aside and got in the middle so he could be the center of attention," Spanakos said. "That was Cassius."

Traditionalists thought his style in the ring also could be a bit much. In late April 1959, at the Pan American Games trials in Madison, Wis., Clay approached John Walsh, Wisconsin's veteran coach, to brag about a first-match victory during which he had danced and taunted his opponent before knocking him out in the second round. Had Walsh seen it? Clay asked. "I couldn't stand it," Walsh replied, according to boxing writer Jim Doherty. "I got up and left."

In Rome, Clay found everything new and exciting, even the bidet in his suite at the Olympic Village, which, according to Spanakos, he mistook for a drinking fountain and tried to take a swig from. Within a few days Clay had established himself as the young clown prince of world athletes. He seemed to be everywhere, shaking hands, telling tall tales, boasting about his prowess, joshing with Olympians from Europe, Asia and Africa. Francis Nyangweso, a boxer from Uganda, recalled coming back from training one afternoon and being approached by athletes wearing USA uniforms. "One of them, very tall and big, spoke to us in an American accent," Nyangweso said. "When I got used to his English, our conversation ranged over topics including wild animals, forests and snakes. Before we parted, this gentleman advised us that the boxer on our team who happened to be drawn against him should duck on medical grounds and should not try to fight him, for he, Cassius Clay, would not like to demolish a young brother from Africa."

Reporters dubbed Clay "Uncle Sam's unofficial goodwill ambassador" and were especially taken by his "solid Americanism" -- a trait he reinforced in an exchange with a foreign journalist. With the racial intolerance in your country, the reporter said, you must have a lot of problems. "Oh, yeah, we've got some problems," Clay was quoted in response. "But get this straight -- it's still the best country in the world."

Over 11 days there had been 280 Olympic boxing matches among competitors from 54 countries, and Nat Fleischer, editor of The Ring magazine, claimed to have watched them all. Several U.S. boxers, Fleischer thought, had fallen victim to cold war politics, with Eastern bloc judges ruling unfairly against them. Clay against Pietrzykowski was the final America versus Iron Curtain bout. Pietrzykowski had been the European champ three times and a bronze medalist at the 1956 Olympics in Melbourne.

In the dressing room Fleischer gave Clay a piece of advice. "I told [him] that if the fight went beyond two rounds," the editor would recall, "he had to go all out to win."

"I'll do that," Clay said.

The first two rounds were close but uneventful. Pietrzykowski, a tall lefty, stayed back, trying to find openings for his long reach. Clay was so quick that he could dodge the Pole's left even with his gloves down. He danced left, skipped right, hands down, then darted in for a punch. Most of Clay's lefts landed just short. The boxing writers talked about what a showman he was but questioned whether he could really take a punch. Neil Allen thought Pietrzykowski won the first round, in which "there was some neat defensive work by both." Povich agreed, recording that Clay "was taking a beating from Ziggy." Most observers felt otherwise, as did the judges, who gave the round (barely) to Clay.

In the second round a furious exchange in the last 30 seconds also favored Clay, but going into the final round the fight was still close. Fleischer's warning registered in Clay's corner. You have to go out there and get him now, he was told.

"The whole picture changed in the third and last round," Allen recorded in his diary. Clay came to life "and began to put his punches together in combination clusters instead of merely whipping out a left jab. He pummeled Pietrzykowski about the ring. Blood came from the nose and mouth of the Pole, and only great courage kept this triple European champion on his feet." Povich wrote that suddenly "Ziggy's whole face was a bloody mask. Clay was throwing punches from angles that were new and he had the Pole ripe for a knockout but in his eagerness and greenness he could not put his opponent away." Still, in the opinion of TheRing's Fleischer, "Clay's last-round assault on Pietrzykowski was the outstanding hitting of the tournament."

By the time it was over, even the Italians in the arena were on Clay's side. One of them was Rino Tommasi, a young boxing promoter and writer. "It was a great night," he said. Clay was both an attractive boxer and a great actor, characteristics equally admired by the Italians. Years later Tommasi would interview Pietrzykowski, who told him that he knew before entering the ring that Clay would beat him and that he was glad he lasted three rounds.

There were no whistles when Clay was announced the unanimous winner. "That was my last amateur fight," he said afterward. "I'm turning pro." He had intended to keep his USA trunks as a souvenir, he added, but "now look at them!" They were streaked with the Pole's blood.

The next morning, Sept. 6, everyone seemed to be up and about early in the Olympic Village. Clay paraded around before breakfast, gold medal dangling from his neck. "I got to show this thing off!" he exulted. His coach said Clay had slept with the medal, or at least had gone to bed with it; the young boxer had been too excited to sleep, as visions of his future flashed in his mind.

"Fool, go someplace and sit down," Lucinda Williams chided him lovingly, like a big sister, when he approached the Tigerbelles and started blabbing that he was the greatest. Clay was always hanging around the Tigerbelles; he had an unrequited crush on Wilma Rudolph.

Dallas Long, the bronze medalist in the shot put, said nothing when he came across Clay that day. He thought, This guy is such a jerk. He's never going to amount to anything. But many other athletes reacted to the young boxer with amused tolerance, not least among them the U.S. Olympic team captain, who was about to compete for a gold medal of his own.

Rafer Johnson was an exemplar of sound mind in sound body. Intelligent and movie-star handsome, he was the student-body president at UCLA. He stood 6' 3" and weighed 200 pounds, with long legs on a muscular, classically sculpted frame. While he was ferociously competitive, he was not as self-centered as most athletes; he had a broad perspective that came in part from having grown up black in a historically Swedish-American town in central California.

Kingsburg, out in the San Joaquin Valley, was about as flat, hot and white as America got. At first the Johnsons were the only black family in town. They had a small one-story house near the railroad tracks in the shadows of a cannery. In the summers Rafer and his four siblings worked the nearby fields, picking grapes, plums and peaches. With one exception, Rafer felt embraced by the community, where, he said, "everyone knew everyone." That lone exception was the police chief, who reflexively suspected the Johnsons when anything went wrong. "Every time something was taken . . . a bicycle missing . . . they came to our house looking for it," Johnson recalled. "We weren't taking anything."

But the prevailing sensibility in Kingsburg, a community that showered attention on its children, was a boon to Rafer. "The parents would build the fields and drive young people back and forth to different competitions," he remembered. "They were the coaches. It was a wonderful community for young people." His best sport was football, but he also starred in basketball and track and field.

Much of Rafer's athletic skill came from his mother, Alma, who could outrun him until he was a teenager. She was also the person he most admired. His father, Lewis, was a hard worker but drank too much. "There were very few Monday mornings when my father was not at work, but there were a lot of weekends when the family suffered because of his drinking problem," Rafer said. "At athletic events, sometimes, honestly, he could be a little disruptive. My mother was able to keep him calm for the most part, but there were times when she couldn't control him and no one else could."

When Rafer was a junior in high school, Kingsburg Vikings track coach Murl Dotson drove him down to watch a decathlon meet in Tulare, the hometown of Bob Mathias, the 1948 and '52 Olympic decathlon champion. Mathias was the hero of the valley. Although there were no decathlons in high school, Rafer returned from Tulare determined to compete in as many of the discipline's individual events as possible and build up his skills so that someday he might succeed Mathias as the best all-around athlete in the world.

His first attempt came at the 1956 Olympics in Melbourne, and it resulted in the most painful loss of his career. The 20-year-old Johnson had gone to Australia as one of the gold medal favorites, but his left knee hadn't fully healed from an earlier injury, and he pulled a stomach muscle while warming up for the first event. Although he gutted his way through the punishing two-day competition, he finished second to teammate Milton Campbell. Failing to win the gold shattered him. The normally stoic Johnson broke down in the arms of UCLA coach Elvin (Ducky) Drake, crying inconsolably. Drake talked to him long into the night, and Johnson emerged with a deeper understanding of what it took to become an Olympic champion.

"When you finish second you have to take a real close look at how you performed, how you thought and how these thoughts caused you to feel," Johnson said later. "We broke those things down." He had heard the words before, but now he absorbed them: "You have to do it on that day. You have to do it at the time when they fire the gun. You have to be fully aware and prepared for anything that might happen."

Now here he was, four years later, nearing the end of the decathlon in Rome on Sept. 6, fighting for survival against Taiwan's C.K. Yang, his UCLA teammate and close friend. Few Olympic athletes knew one another as thoroughly as Johnson and Yang. It was not just that both had trained at the same college for the same event. A deeper shared sensibility seemed to be at work, a blend of admiration and competitiveness that pushed them to greater accomplishments than they might have achieved apart.

Track experts had virtually awarded the gold medal to Johnson before the Games, and Johnson himself had been quoted as saying that Yang would finish second -- but privately, he would say later, he was "nowhere near as cocky as that statement suggests." They knew each other's strengths and weaknesses intimately, as did the coach they shared. Drake, who had not been appointed to the U.S. track and field staff, came to Rome officially as Yang's coach, but he tried to show no partiality for either of his two great decathletes, devoting equal time and attention to each.

Eight events down, with only the javelin and the 1,500 meters to go. Darkness had fallen by the time the decathletes got to their final javelin throws. A full moon glowed over the Stadio Olimpico. Yang, chilled by the night air, wrapped his shoulders in a blanket. Johnson knelt patiently, chewing a wad of gum. The competition had been intense all this second long day. Yang had snatched the overall lead after the 110-meter hurdles; then Johnson had taken it back with the discus, only to watch his margin shrink with the high jump. The javelin usually provided Johnson's safety cushion; with it he would amass enough points to withstand any charge in the 1,500. In Rome he tried to turn his mind off and just perform, but his approach on his final throw was too slow, and he felt sluggish. He would have to settle for just under 230 feet -- six feet better than Yang but not enough to make Johnson feel comfortable. Here came the 1,500, and Johnson was leading by only 67 points.

He and Yang were in the same heat. Fluent in the decathlon's arcane scoring system, both men calculated that if Yang won the race by 10 seconds or more, the gold medal was his. This was far from improbable; Yang's best time was 4:36.9, while Johnson's was 4:49.7 -- a spread of nearly 13 seconds.

In the front row of the Stadio Olimpico stands, near the 330-meter mark, sat Ducky Drake. Go about your work with a quiet confidence that cannot be shaken, he had often told Johnson during anxious moments. Johnson's confidence was not shaken now, but he felt he needed more advice, so he approached his coach at the edge of the stands. How should he run this most important race of his life? The key thing, Drake said, is that when Yang tries to pull away -- and he will try -- you have to stay with him. At some point Yang will look back to see where you are, and you have to be right there.

Easier for Drake to say than for Johnson to do, but still, it was perhaps the only plan that could save him. Johnson nodded in agreement and walked back toward the track. About halfway there he turned around and saw none other than Yang approaching the same spot at the edge of the stands. Drake, after all, was his coach too.

"Ducky said to me, 'C.K., you run as fast as you can,' " Yang later recalled. " 'Rafer cannot keep up with you!' " Drake was like a master chess player competing against himself. He saw the whole board and was making the best move for each side.

But Yang was not convinced Johnson could not keep up with him. He knew how competitive Johnson was. Even if Yang was much better at this distance, he felt uneasy. What if he tried to pull away and got a cramp, as he had at an AAU meet a few months earlier in Oregon?

They approached the starting line at 9:20 p.m. "The pressure was on. I don't know if I've ever felt more pressure than I felt starting that race," Johnson recalled. "It's like I couldn't breathe."

There were four other runners in the race, but they were inconsequential, like ghosts. All eyes were trained on Johnson and Yang. After a late workout Newell and some of the U.S. basketball players took seats near Drake to watch the climax. Most of the Tigerbelles were there, too, rooting hard for Johnson. Williams said she and her teammates all had crushes on their captain, "but he was too focused to look at anybody. He was the greatest."

The darkening night, the sense of autumn coming, of something ending, added to the tension. As the race got under way, SPORTS ILLUSTRATED's Tex Maule jotted down his impressions of Johnson: "His strong, cold face impassive, the big man pounded steadily through the dank chill of the Roman night. Two steps in front of him, Formosa's Chuan Kwang Yang moved easily. In the gap between them lay the Olympic decathlon championship."

Johnson ran the first two laps with determination. "I stuck to him like a shadow, dogging his footsteps stride for stride," he said of Yang. Midway through the race Yang picked up the pace, but Johnson stayed with him, shifting his position from Yang's left (inside) shoulder to his right shoulder. He wanted to be fully visible when Yang turned around. Just as Drake had predicted, Yang did turn around. He was stunned to see Johnson at his right shoulder. Not only that, Yang would recall, but "he looked like he was smiling."

Johnson did indeed smile, but it was pure acting. "I just wanted to let him know that this was going to be different," he would say later. "I could have had my head down and dragging, because I was feeling that kind of fatigue and pressure, but I smiled as big a smile as I could."

By the final lap, memories of the Oregon trials seeped into Yang's head. He worried that he might cramp up again. But how else could he shake the big guy? He had no choice but to try one more acceleration, one final push to break clear. It seemed to work for a short time, but then Yang felt his body weakening. Coming around the turn, he looked back again, and there was Johnson, clinging to him, only three yards behind.

Johnson tried not to think about the ache in his legs. He was "struggling so hard," noted Allen, "that we in the stands could almost feel his pain." But he had one crucial edge over Yang. "My huge advantage was that this was the last time I was going to do this," he recalled. "And C.K., he had several more times. I kept saying to myself, This is it. Just this one more time. I can do this one as good as I've done it. I would never run the 1,500 again. Never. Never. More important, I would never run it at the end of doing nine other events."

Maule called that 1,500 "the tensest five minutes of the entire Games. And it grew and grew until it seemed like a thin high sound in the stadium." Down the homestretch Yang was bobbing and struggling, while Johnson was moving mechanically, sheer will driving him forward. They crossed the line only 1.2 seconds apart, Yang at 4:48.5, Johnson at 4:49.7. Johnson had tied his best time.

Yang knew he had lost the decathlon. A few steps after finishing, his close friend and tenacious foe caught up to him. Johnson felt at once jubilant and sad. "I never in my whole life but that once competed against someone where I had a little bit of ambivalence about beating him," he would explain later. "I was exhilarated that I won and totally depressed that C.K. lost."

As they came to a stop, Johnson put his head on Yang's shoulder. Yang bent down to catch his breath, and Johnson bent with him, hands on knees, as officials and photographers rushed toward them in the artificial light of the stadium. Johnson straightened and walked around, arms akimbo, smiling and shaking hands with well-wishers, utterly out of breath. Yang slipped over to a bench and put his head in his hands in despair. He got up, jacket around his shoulders, head bowed, and found a Taiwanese official who hugged him and patted him on the back.

A few seconds later Yang was bending down again when Johnson appeared, lifted him up and stood with him arm in arm. "It was a moment of such beauty," Allen wrote in his diary, "that I was not surprised to see one friend in the press box with tears in his eyes and I for one, for the first time in my life, found that my hands were trembling too much to type."

At 11 o'clock that night, after back-to-back 14-hour days of competition -- 10 events, draining humidity, evening chill, rain delays, unbearable tension and the accumulation of an Olympic-record 8,392 points -- Rafer Johnson left the Stadio Olimpico for the last time, retracing the steps he had taken nearly two weeks earlier as the captain and flag bearer for the U.S. team. As he trudged, exhausted, along the moonlit Tiber and over the bridge, C.K. Yang, no longer a competitor, now solely a friend, walked once again at his side.