Peter Boulware goes door-to-door in race for seat in the Florida House

TALLAHASSEE, Fla. -- Somewhere along the path from the end of his football career to here -- standing under a blazing August sun waving at motorists as they drive by the Leon County Courthouse -- Peter Boulware decided to take a detour that those close to the NFL star never saw. "I couldn't believe it,'' said Melva Boulware, Peter's mom. "This is not part of the Peter I expected once he finished playing football.''

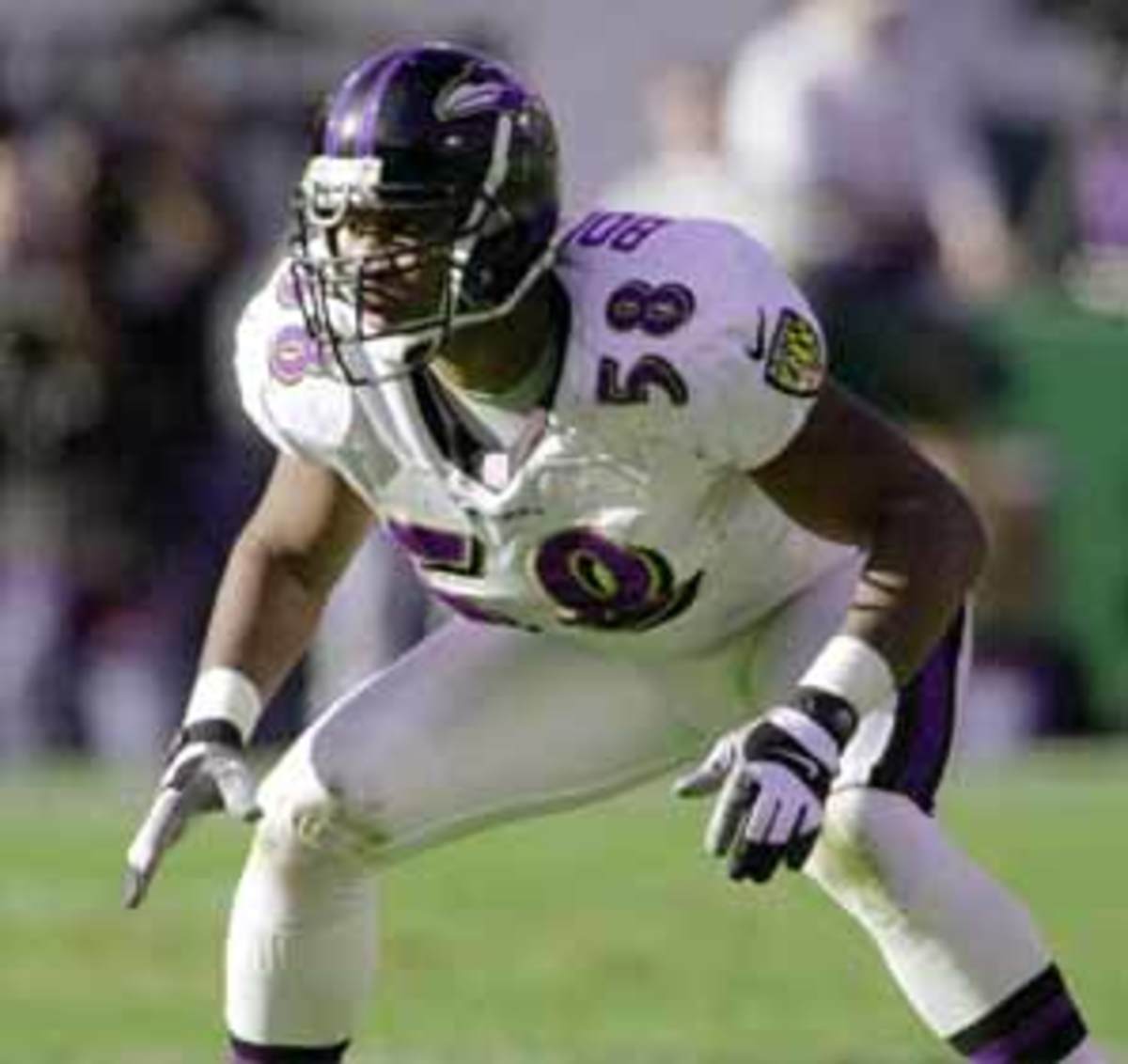

In a few days, the Baltimore Ravens' career sacks leader (70 from 1997 to 2005) will know if he'll have similar success in his first foray into politics. Next week Florida voters head to the booth to vote in a Leon County primary election pitting Boulware against fellow Republican Jerry W. Sutphin. If Boulware wins the primary, he'll be one victory away from earning a seat in Florida's House of Representatives.

Somewhere in his transition from chasing quarterbacks to chasing votes, Boulware relied on a piece of advice Florida State's Bobby Bowden delivered to the Seminoles during Boulware's All-America stint at FSU more than a decade ago. Don't go to the grave with life unused. Boulware recalled those words as he contemplated the beginning of his latest journey, inspired by Bowden's guidance enough to use the phrase in his official introduction letter on his campaign Web site.

Two hours after arriving at the courthouse along with a few volunteers holding signs and wearing T-shirts that read "Peter Boulware For Florida House,'' Boulware is dripping in sweat. With the election nearing, Boulware spends the majority of his time making public appearances similar to this one. "This is like training camp for me,'' Boulware said. "This is politics at the grass-roots level. It's been a good experience for me. I'm not a politician. I'm learning as I go.''

Running in a district that voted 52 percent Democrat and only 34 percent Republican in the 2006 election, Boulware is aware of the obstacles ahead. Still, he also knows he has name recognition, plenty of business connections as vice president of a successful Tallahassee car dealership, a strong network of campaign fundraisers and millions left over from the hefty paychecks he received during a nine-year NFL career.

Since retiring from the NFL after the 2005 season, Boulware has spent most of his time focused on his wife, Kensy, and their three young children. The couple is expecting another child in December. Boulware's reputation around this garnet-and-gold town is nearly as formidable as Bowden's. He first moved to Florida's state capital from Columbia, S.C., in 1993 to attend FSU, where he met Kensy, a former FSU volleyball player. They decided to make the city their home after marrying.

"The name Boulware is just one of those great names in Florida State history,'' said FSU junior safety Myron Rolle, expected to be nominated as a Rhodes Scholar candidate this fall. "I hope he wins. Every time we hear his name and see his highlights on video, there is a little awe that goes through us and a little chill that goes through our bones because we know he was such a great player while he was here.''

With everything Boulware has going for him, the obvious question is this: Why is the four-time Pro Bowl defender running for political office? "When the seat was first presented to me, I said, 'No way possible. I'm not a politician,''' said the 33-year-old Boulware. "But people told me that's what we need, someone who is not a politician to come in and provide a fresh outlook.''

Boulware announced his candidacy last September, only two years after knee and toe injuries forced him to cut his NFL career short. The announcement made national news and his decision caught his family and former teammates by surprise. "We just never thought he would go this way,'' said Boulware's father, Raleigh. "This is totally new, totally unexpected. Early in his [football] career, he was kind of shy about making speeches, and now he is doing something that requires him to make speeches all the time.''

Boulware's younger brother, Michael, also a former FSU standout who currently plays for the Minnesota Vikings, asked his brother what many others were thinking: "Are you crazy, man?''

Peter explained that he was ready for a new challenge, even one as unexpected as running for office. "I love this area," Boulware said. "I want to help the people who live here. This is where I met my wife and where we are raising our kids. I'll do it as long as I can make a difference. The key is that I have to get in and win first.''

A couple of miles from where Boulware stood waving at passing motorists, Bowden had spoken in the shadows of Doak Campbell Stadium the day before about his former player's latest endeavor. "I've seen the [campaign] signs,'' Bowden said. "Peter was one of those guys who came in with good credentials and left with good credentials. He was never a problem in class or off the field. Peter would be good at whatever he does. He is a very, very educated and class individual who has a very good record. I think he'll be excellent.''

Following his campaign appearance outside the courthouse, Boulware and a campaign representative walk a few blocks across town for lunch with a couple of local optometrists. They talk about the election, Boulware's stance on certain issues, what they can do to help, and whether Boulware needs anything other than the envelope containing a campaign donation one of the men handed him as they sat down to lunch. In between sips of ice tea and bites of a sandwich, Boulware sounds as if he has played this game for longer than 11 months.

"What I really need is to meet as many people as I can,'' Boulware said. "If you can help introduce me to people who would be good for me to meet, that would be a big help.''

The men trade business cards with Boulware and say they will call to set up some meetings. Lunch is over, but Boulware's day hasn't even reached halftime. About an hour later, Boulware meets several campaign volunteers in the parking lot of a local Starbucks. The volunteers are mostly college-aged kids who know Boulware more for his 70 career NFL sacks than any of his political ideas. They break into three teams, armed with addresses of approximately 300 homes in the surrounding neighborhoods.

With the mid-afternoon heat shooting into the 90s, it's time to hit the pavement for some door-to-door campaigning. Boulware steers his Toyota Tundra pickup truck through a nearby neighborhood, tossing a child's car seat into the back to make room for a pair of visitors. When someone reminds Boulware that this is a long way from the NFL, he smiles with an "I know" look.

"It's humbling to go from an NFL player, living the high life, signing autographs, to walking around knocking on doors,'' Boulware says. "As an NFL player, you kind of get detached from reality. [This] feels like you are at the bottom and you've got to work your way up. I'm fighting for every vote. People know me as a football player, but they don't know me as a public servant. It's really about listening to people.''

What's he hearing? "The economy is huge,'' he says. "Education is always big. People want to make sure their kids are getting a great education.''

As Boulware drives, Dan Dawson, an FSU senior helping with the campaign, reads off addresses. They have 88 houses on their list, known as a walk-pack in campaign lingo. For the next hour and a half, Boulware and Dawson go from house to house knocking on doors. Most people aren't home, so Boulware and Dawson leave campaign flyers by the front door to spread the word. When people do answer, Boulware uses a similar opening line each time: "Hi, I'm Peter Boulware and I'm running for the House. We're just walking the neighborhood to meet people.''

"It's good to have people working the streets,'' one man says.

"Hey, it's nice to meet you. I'm planning on voting for you,'' says a middle-aged woman.

"Yes, Peter, I remember you,'' replies an older man with an FSU flag hanging off the house.

Boulware says most folks are nice or indifferent during the door-to-door stops. A few have asked for autographs or a picture. He has learned to keep most stops brief in order to maximize use of his time. "Once I got stuck in a house for 45 minutes,'' he says.

On this day, Boulware avoids any unexpected delays and makes it to every home on the list. He'll replay the exercise several times until the election, often joined by his strongest supporters, Kensy and their three children. Boulware has shed about 30 pounds from his 6-foot-4 frame since retiring. He still works out when he can and looks as if he is ready for training camp. Of course, his body knows otherwise.

The knee and toe injuries that ended his career prematurely cost him that initial burst of speed needed to be a premier pass rusher. Once that was gone, Boulware knew it was time to quit, a difficult reality for someone who played in 111 consecutive games from his rookie season in 1997 through 2003, another franchise record he still owns. Before the injuries, Boulware was considered among the best defensive players in the league. In 2001, he recorded a franchise-record 15 sacks. The season before, he and fellow linebacker Ray Lewis anchored perhaps the best defense in NFL history, helping the Ravens beat the Giants in Super Bowl XXXV, limiting New York to 152 total yards.

Boulware had everything mapped out back then. "I was in the prime of my career,'' he said. "I figured I would play four or five more years and would make the Hall of Fame. That was my goal. You never know when it's going to end.''

Boulware recently watched an episode of the HBO documentary Hard Knocks about the Dallas Cowboys' training Camp. The behind-the-scenes footage reminded him of his playing days, even bringing back some of the smells and tastes of playing in the NFL. He says he doesn't miss the game now that he has had time to separate himself from it.

"This time of year, training camp, two-a-days, it's such a grind,'' he said. "I'm so glad I'm not doing that right now. When I talk to my brother, I tell him I'm glad it's him and not me.''

Instead, the personable Boulware is walking around neighborhoods, making speeches and shaking hands, all in an attempt to earn votes. He's tackled his latest venture the same way he relentlessly bullied his way into backfields during his playing days. Longtime FSU defensive coordinator Mickey Andrews isn't betting against Boulware. Andrews watched Boulware go from a tall and lanky freshman to one of the best defensive players in school history. Boulware's 19 sacks in 1996 set a Florida State single-season record that still stands.

"He wasn't a great player when he got here. He made himself into a great player,'' Andrews said. "He almost didn't get past the first day we had mat workouts. You'd have to think from what you've seen him do in football and other things that he'll be successful in it.''

Win or lose, Boulware is determined not to leave any life unused. "Everything you do you want to win and be successful at,'' he said. "I'm not going to get outworked in this thing.''