The Goof That Changed the Game

It was nearly 30 years after the game -- that game -- and, Marianne Merkle remembered, even church wasn't a safe haven. One Sunday morning in the 1930s, Merkle and her family were attending services in Florida, when a visiting minister introduced himself. "You don't know me," he piped, "but you know where I'm from! Toledo, Ohio! The hometown of Bonehead Fred Merkle!"

Little Marianne knew what would happen next. "The kindness drained from [my father's] face," she told me five decades later. Then Fred Merkle rose and wearily told his wife and daughters, "Let's go."

It was a moment to which Bill Buckner could relate. Ralph Branca, Mickey Owen, Chris Webber, Scott Norwood and, most recently, Desean Jackson and Ed Hochuli too. Like Merkle, they faced ridicule and visceral hatred and humiliation. Only Merkle faced it first and has faced it the longest. For his moment happened at the point in history when sports was becoming America's cultural currency, its winners and losers more familiar than our neighbors. One hundred years ago today, Fred Merkle became our first goat.

On Sept. 23, 1908, baseball's greatest pennant race (the top three teams in the National League would finish within a game of each other; the top three in the American, within a game and a half) was raging. Against the Cubs that day at New York's Polo Grounds, Merkle, a 19-year-old Giants rookie, made his first start of the season, in place of the Giants' injured regular first baseman. The teams were tied for first place and tied 1-1 in the bottom of the ninth, with two out and New York's Moose McCormick at first. Merkle laced a long single to rightfield, sending McCormick to third. On the next pitch shortstop Al Bridwell singled up the middle, apparently giving the Giants a crucial victory set up by a clutch hit from Merkle.

What happened next has been debated for a century. As McCormick neared the plate Giants fans stormed the field, both to celebrate and to beat the quickest path to the elevated trains and streetcars beyond the rightfield fence. While the diamond was overrun, the Giants, as players did in such situations then, began sprinting for the safety of their clubhouse in centerfield. Merkle, heading for second, took a right turn and joined the exodus.

Few people in the park knew it, but Merkle's decision violated what was then Rule 59: A run could not count if another runner was forced as the third out of the inning. Fans frequently took to the field in those days, but exhaustive research has not turned up an earlier instance of Rule 59 being enforced on what we now call a walk-off hit. But by the letter of the law, McCormick's run could be nullified if the Cubs touched second before Merkle.

Without film or still photographers there to capture the moment, there are a dozen competing stories about what followed. But somehow, in the chaos, Cubs second baseman Johnny Evers got a ball (nobody ever proved it was the one Bridwell hit) from centerfielder Solly Hofman and stepped on the bag. Umpire Hank O'Day called Merkle out, canceling the winning run. With the Polo Grounds engulfed in dusk and angry fans, he declared the game a tie.

The aftermath was worthy of Greek tragedy. The Cubs and the Giants finished the season tied for first place, forcing a replay of the game at the Polo Grounds on Oct. 8. Chicago won the game and the pennant, then rolled over the Detroit Tigers to win the World Series -- their last, Merkle defenders and Chicago jinxologists will remind you. National League president Harry Pulliam, who upheld the ump's ruling and forced the playoff, was so vilified for his decision that he suffered an emotional collapse. He died by his own hand nine months later.

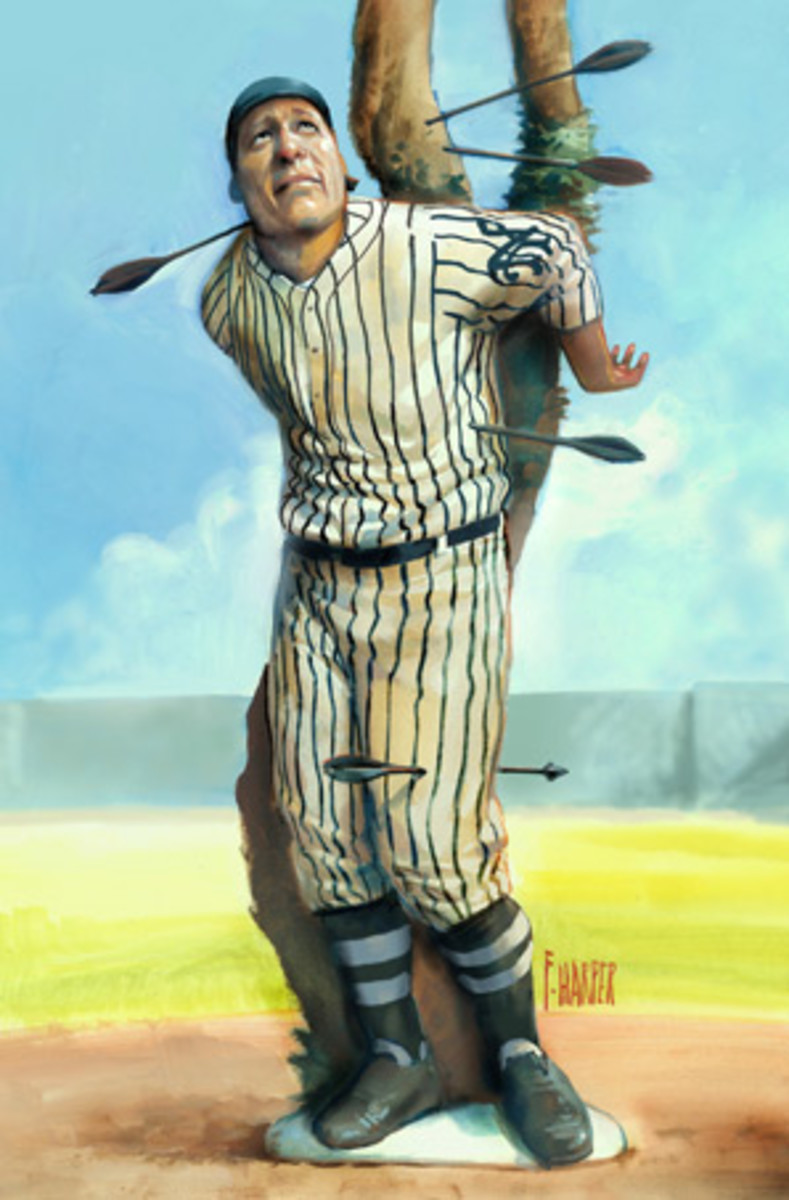

Merkle, though, attained a level of infamy that makes Buckner's travails seem trivial. Crowds had held grudges against athletes before him, but fandom changed with his misfortune. It got personal, and a failure to abide by a previously unenforced rule was suddenly reason to impugn a player's intelligence and character. Merkle became the Bonehead, his failure to touch second forever known as Merkle's Boner. Pulling a Merkle entered the lexicon as slang for any kind of airheaded mistake. Under a headline that read BLUNDER COSTS GIANTS VICTORY, the next day's story in The New York Times began harshly: "Censurable stupidity on the part of player Merkle... " The criticism, with its subtext of almost impossible imbecility, was unprecedented -- and, since Merkle had done exactly what any other player would have, undeserved. And it never ceased.

"He didn't talk about it much," Marianne told me. "But he did tell me that as long as he wore a uniform, not a day went by when somebody didn't call him Bonehead, or shout, 'Don't forget to touch second!' " Still, Merkle played 14 more seasons in the big leagues and was on six pennant-winning teams. (All of them lost the World Series.) He batted .273 lifetime, stole 20 or more bases eight times, became a minor league manager and was acclaimed by Giants catcher Chief Meyers as "the smartest man on the ball club."

Embittered by the venom of the fans and the media, Merkle receded from the game in the 1920s (he quit a minor league managing job after a player called him Bonehead) and sold fishing tackle in Florida. He avoided the game until 1950, six years before his death, when the Giants invited him back for an Old-Timers' Day. Merkle startled his family by accepting. Marianne said he figured another round of catcalls was the price of communing with the friends of his youth one final time.

Instead, when he was announced at the Polo Grounds, fans applauded and cheered. Sportswriter Barney Kremenko later claimed the roar was as loud and heartfelt as the one that followed Bobby Thomson's homer the following year. Merkle and the fans made peace with one another. The pain was relieved, the blame absolved.

Yet that absolution isn't what's remembered about Merkle each Sept. 23. We love our heroes, but beginning with him, we've loved to hate our goats just as much.