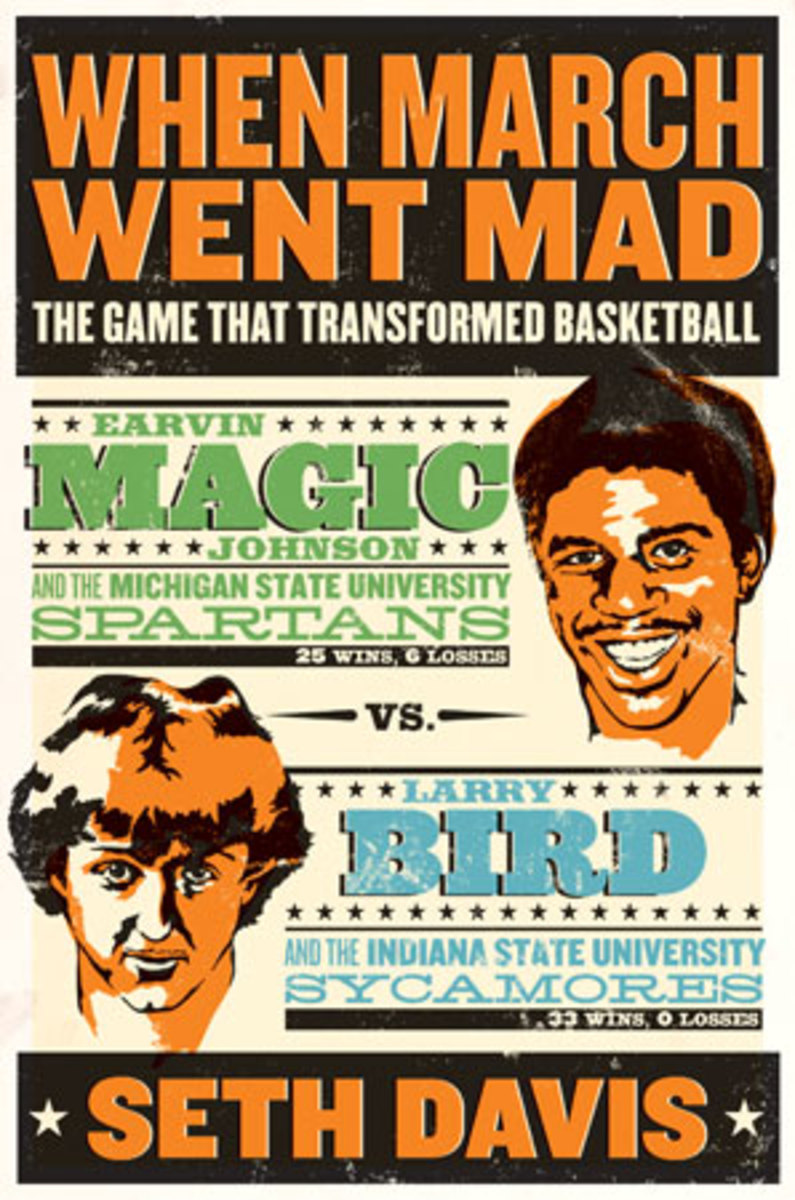

When March Went Mad

From the Book, WHEN MARCH WENT MAD: The Game That Transformed Basketball by Seth Davis. Copyright © 2009 by Seth Davis. Published by arrangement with Times Books, an Imprint of Henry Holt and Company, LLC. All rights reserved.

Larry Bird had been intensely shy ever since he was a youngster. According to Jim Jones, his former high school coach, Larry once flunked an English class because he didn't want to give a speech. When his older brother, Mark, was leading Springs Valley High School to a state sectional championship, Larry didn't go to the games because he didn't like crowds. Even his mother, Georgia, used to say that Larry was the only one of her six children whom she often couldn't tell what he was thinking. "Larry only tells you exactly what he wants you to know," she once said.

Larry's upbringing was not exactly the best training ground for facing the klieg lights of the national media. "It would have been difficult to find anyone less prepared to be interviewed than I was when I got to Indiana State," he wrote in Drive. The Birds were among the poorest families in French Lick, which was located in the poorest county in the state, Orange County. Throughout Larry's childhood, his father, Joe, was in and out of jobs as he battled alcoholism. He finally landed steady work at the Kimball Piano Factory in town, where he worked as a wood finisher for eight years. Georgia Bird often worked two jobs at a time, usually as a waitress. The Birds rented seventeen houses in eighteen years until they finally bought a house on Washington Street.

"My kids were made fun of for the way they dressed," said Georgia. "Neighbor boys had basketballs or bikes. My kids had to share a basketball. A friend of Larry's would say, 'If you can outrun me down to the post office, you can ride my bike for ten minutes.' Larry used to run his tail-end off."

Though by all accounts Joe was a loving father, he and Georgia fought often, especially when his excessive drinking brought on more financial hardship. They divorced when Larry was sixteen. Joe's alcoholism was apparently caused, or at least exacerbated, by posttraumatic stress disorder that resulted from his tour of duty for the U.S. Army in Korea. The experience gave Joe such violent nightmares that Georgia warned family members never to touch Joe when he was sleeping, lest he wake up suddenly with his fists flying.

According to Georgia's sister, Virginia Smith, who wrote a memoir describing Larry's childhood, some of those arguments turned physical. "One summer day [Georgia] arrived at our farm sporting a beauty of a black eye and a cut, which had required stitches, above the eye," Smith wrote. "Although she was pregnant, Joey had hit her, breaking her glasses and forcing her to flee. The next day, Joey came to our farm, sincerely sorry for his actions. He always was regretful for any harm he caused, after he sobered up."

Seth Davis on the legacy of the Magic vs. Bird NCAA Tournament showdown

Much like Larry, Joe Bird was a quiet, remote person who didn't like being in large crowds. Even some of those closest to Larry didn't know Joe. "I would see Larry's dad at games, but he never sat," says Jan Condra, a former Springs Valley cheerleader whom Larry began dating during their senior year. "He would stand at the end of the gym by himself under one of the goals. I don't believe I ever spoke to him."

But Larry knew full well that his father, like nearly everyone in French Lick, was a huge Indiana University basketball fan. As Larry started putting up huge numbers on the basketball court his senior season at Springs Valley -- he averaged 31 points and 21 rebounds in 1973-74 -- he began hearing from everyone in town that he should attend college in Bloomington. Not surprisingly, he was uncomfortable receiving all the attention. When Bird saw his name in a local newspaper, he complained to his new coach, Gary Holland, "Why can't we get Beezer's name in the paper some too?" (Holland had replaced Jim Jones, who had retired; James "Beezer" Carnes was Larry's best friend and teammate.)

His reclusiveness also made him a tough target for recruiters. One day, Denny Crum, the head coach at the University of Louisville, came to town and challenged Bird to a game of H-O-R-S-E. If Crum won, Bird would have to visit Louisville, about sixty miles away. Bird said okay. Then he beat Crum in about eight shots. Larry never did make the trip.

The school he most wanted to attend was Kentucky. Bird went with Holland and his parents on an official visit to Lexington, but Wildcats coach Joe B. Hall, who had been to Springs Valley to see Larry play, didn't offer him a scholarship. "People give Joe B. Hall hell about that, but I'm close friends with one of Joe's assistants, and he said when you talked with Larry Bird, he wouldn't talk to you; he wouldn't look at you," Bill Hodges says. "Ain't no way a Kentucky player can get by like that. They'd eat him alive."

Bird's eye-popping high school numbers eventually caught the attention of Indiana coach Bob Knight, who dispatched his assistant, Dave Bliss, to French Lick to see how good the kid really was. "He was wonderful to watch because he would pass the ball better than anybody on the floor, he would shoot the ball better than anybody on the floor, and he would try harder than anybody on the floor," Bliss says. Developing a relationship with Bird, on the other hand, wasn't easy. Aside from one occasion when Bird shared his preferred hobby of mushroom hunting ("I'd never heard of it. I'm a Protestant from upstate New York," Bliss says), most of Bliss's contact was with Jones and Holland.

Knight also attended several of Larry's games himself. During one conversation in Holland's office, Knight asked Larry which other schools he was considering. When Larry mentioned Indiana State as a possibility, Knight shot back, "If you're thinking about going to Indiana State, you shouldn't bother coming to Indiana."

It wasn't until the spring of 1974, when another player Knight was recruiting opted for the University of Cincinnati, that Indiana officially offered Bird a scholarship. Sensing that Bird still needed some prodding, Knight took the unusual step of asking three of his own players to drive to French Lick and meet Bird for lunch. John Laskowski, Kent Benson, and Steve Green made the trip and ate with Bird and Jones at a local Pizza Hut.

When they returned to Bloomington, Knight asked Laskowski how it went. "Well, Jim Jones seems like a really nice guy," Laskowski said. "But that Larry Bird, he didn't say a word."

Bird decided in April to sign with Indiana. That moment was a matter of great civic pride for his community, but those closest to Bird sensed his heart wasn't in it. "I know he respected Bob Knight, but I really think he went because other people pressured him to go," Beezer Carnes says. "He's the type of guy who doesn't like to let people down."

Bloomington is only fifty-six miles from French Lick, but for Bird it might as well have been a world away. When he arrived during the summer of 1974, he found himself rooming with Jim Wisman, a six-foot-three guard from Quincy, Illinois. Wisman's father was a mail carrier, and though his family was by no means wealthy, he seemed plenty well-to-do in Bird's eyes. "I made a mistake rooming Bird with Jim Wisman," Knight later said. "Bird had no clothes, and Wisman's closet was full. Wisman was real smart and could speak well. Bird was not, and couldn't, at age eighteen." Though Wisman generously told Larry he could wear his clothes whenever he wanted and even lent him money from time to time, Larry knew that couldn't last. On several occasions, he called home and told Georgia he wanted to leave, but she convinced him to stay.

When it came time to scrimmage with the older players, Larry thought he was treated badly by some of the team's veterans -- especially Benson, who went out of his way to haze Bird and give him the full freshman treatment. "The philosophy in the old days was, until you prove you're ready to be on the team, then you're just a freshman," Laskowki says.

"A lot of times he was fairly unhappy with his performance [in the pickup games]," Wisman said. "Larry was much more relaxed when he could just go off and shoot. That's where he was really at home."

The start of classes only intensified Bird's feelings of isolation. Here he was, a poor, sheltered, intensely introverted teenager who had barely set foot outside his hometown of fewer than three thousand people, and he was stuck without any friends on a campus of more than thirty thousand undergraduates. He couldn't get over the fact that he had to walk several miles just to get to class. And, as he often said half-jokingly, "I ain't no genius in school."

If he thought he might get some emotional support from the coaches, that notion was quickly dispelled as well. One night, while walking down the street with Jan Condra, who had also enrolled at Indiana, at Larry's behest, and her sister, Larry looked up and saw Knight walking toward them. He stiffened and readied himself to speak to his head coach for the first time since arriving on campus. Knight walked toward Bird; Bird said hello -- and Knight blew by without saying a word. "Larry didn't say anything, but I could tell with his demeanor that his feelings were hurt," Condra says. "Larry was used to people being a lot nicer to him. He didn't like Coach Knight's personality."

Knight would later regret treating Bird so coldly. "Larry Bird is one of my great mistakes," he said. "I was negligent in realizing what Bird needed at that time in his life."

The final straw came in late September when Larry received a bill for sixty dollars to cover the fee for a bowling class. Bird assumed he wouldn't have to pay the fee, and he sure as hell didn't have the sixty bucks. So he went to the basketball office, and, after being made to wait for what felt like a long time, he told assistant coach Bob Weltlich about the bill. Weltlich, in a manner that Larry considered abrupt, told Larry that it was his responsibility. End of meeting.

That was it. Larry immediately went back to his room and asked Georgia -- again -- if she would come pick him up. Once again, Georgia said no. Larry called his girlfriend and told her he was leaving. Then he packed up what few belongings he had and, leaving behind a small refrigerator he had brought with him from French Lick, headed out the door. When Wisman returned to find him packing, Larry said he was leaving and asked Wisman not to tell the coaches. Ignoring his roommate's pleas to reconsider, Larry headed out to Highway 37 and stuck his thumb in the air. Eventually, a man in a pickup truck pulled over to give him a lift out of town. It was left to one of Bird's uncles to call Knight and inform him that Larry had left and he wasn't coming back.

Georgia was so furious she didn't speak to Larry for weeks. For the next several months, he lived mostly at his grandmother's house. "Oh, I can be moody like Mom," he said. "One thing can make me mad for two days. Only she'll stay mad over one thing for two months." Two of Larry's uncles were also hard on him for leaving Bloomington. "They would give him the cold shoulder and tell him how disappointed they were in him," Condra says. "That was a time where he needed support from his family, and his uncles didn't give it to him."

Larry enrolled at Northwood Institute, a junior college in French Lick's neighboring town of West Baden, but it didn't take long for him to realize the competition there was weak. He quit after two weeks. "He was very unsettled," said Northwood's coach, Jack Johnson. "He had trouble attending class and was very undisciplined."

With no team to play for and no school to go to, Larry decided to take a job with the French Lick streets department. He would ask his good buddy and crewmate Beezer Carnes to pick him up at the crack of dawn so they could get there early. When Beezer would inevitably be late, Larry walked to work instead of waiting for him. "That's just the kind of work ethic he has," Carnes says. "Larry would get on a tractor and mow the grass. We'd collect garbage, dig ditches, clean out the trucks, paint curbs. He loved it. If he hadn't done what he did as a basketball player, I'd say he'd be the French Lick street commissioner right now."

In future years, as Larry Bird's celebrity burgeoned, his experience on the garbage truck would draw considerable interest, as well as a smattering of elitist derision. Larry, however, never saw it as beneath him. "I loved that job," he said in 1988. "It was outdoors, you were around your friends. Picking up brush, cleaning up. I felt like I was really accomplishing something. How many times are you riding around your town and you say to yourself, Why don't they fix that? Why don't they clean the streets up? And here I had the chance to do that. I had the chance to make my community look better."

"In French Lick, people respect people who will work, no matter what the job," says Chuck Akers, a close friend of Larry's and a former gym teacher at Springs Valley. "They don't look at work as degrading. They don't think any less of someone who works on a garbage truck than a guy who works at a bank." Bob Heaton, Bird's future teammate and roommate at Indiana State, has no problems envisioning Larry as the French Lick street commissioner. "Larry says working on that trash truck is some of his best times, and knowing Larry I'm sure it was fabulous," Heaton says. "No stress, working with his friends, being outside. Larry's favorite thing to do is cut grass. He always said nobody could cut grass better than him."

As much as Bird enjoyed his job, it could not feed his competitive jones the way basketball did. So at Akers's behest, Larry agreed to play for the AAU (Amateur Athletic Union) basketball team Akers had been playing for that was based out of Mitchell, Indiana. This was a much higher level of competition than Larry found at Northwood, yet he dominated those games just as he did in high school. His performances once again brought college recruiters out of the woodwork -- Larry would spy a sharply dressed man in the stands and know instantly he was an outsider -- but Larry brushed them off. He was having too much fun to think about going to school.

Playing for that AAU team also gave Bird a chance to travel. He loved the camaraderie of the road trips, especially since they gave him plenty of chances to pull off juvenile pranks. Akers remembered a time when Larry sat in his hotel room and called two other rooms pretending to be an attendant from the front desk. Larry "apologized" to the strangers as he informed them they would have to change rooms. "So he peeps out the door and he says, 'They're passing each other in the hall!' He was just a kid," Akers says. "He enjoyed traveling so much. We'd tell him, this is what college ball is like. You go on trips and you play in games."

Despite the embarrassment of having dropped out of Indiana, the fall and early winter of 1974-75 was a happy time in Larry's life. That bliss, alas, was shattered in February 1975, when Larry's father committed suicide. Joe Bird had become increasingly depressed and strapped for money. When a police officer showed up at his house looking for child support, Joe asked him to come back later that afternoon. Then he shot himself in the head with a shotgun. His suicide was big news in French Lick, but Larry rarely spoke of it, even among his closest friends. "Larry loved his dad a great deal, and he didn't like talking about it," Beezer says. "I didn't bring it up, either. That's just something that he dealt with himself. But believe me, he took it hard."

Just two months after Joe Bird took his life, Bill Hodges reported for his first day of work as an assistant coach at Indiana State. He met that morning with Bob King and the other assistants to discuss recruiting. As King went over Indiana State's current roster and a list of potential prospects, Hodges asked him, "Are you recruiting Larry Bird?"

King had heard of Bird and knew he had dropped out of Indiana University the previous September, but unlike Hodges he had never seen Bird play. "He's on our list," King said. "Is he good?"

"Oh yeah, he's good," Hodges said. "I bet he could start for us right away. Probably average about eighteen a game."

"You better go see him, then," King said.

The following day, Hodges and Stan Evans drove two hours south to French Lick. They didn't even know if Bird would be in town, so they planned to drive to Springs Valley High School and ask Larry's old coach, Gary Holland, to help them find him. Hodges intentionally didn't tell Holland they were coming. "When you need someone's help in recruiting," Hodges says, "you don't give them a chance to say no."

They found Holland in his office at the high school gymnasium, and the coach said he'd be glad to take them out to the small, singlelevel house on Washington Street where Larry lived. Hodges stood on the front porch and knocked on the door. When Georgia Bird answered, Hodges started to tell her who they were and why they were there, but Georgia cut him off. "Why do all you coaches keep bothering him?" she asked. "He doesn't want to go to college. He's not interested."

"Well, we think Indiana State might be a good place for him," Hodges said.

"He's not interested," Georgia repeated. She shut the door in his face.

Hodges looked over at Holland, who could only shrug. She wasn't usually like that, he said. Holland suggested they look for Bird at his grandmother's house. When they got there, however, nobody was home. Holland told them he would try to find Larry another time and promised to pass along the message. Evans suggested to Hodges that they leave. "Aw, hell, let's keep looking," Hodges said. "There can't be too many six-nine kids walking around this town."

They checked out a local pool hall, but Larry wasn't there. They stopped by the Shell station where a lot of the young folks in town hung out. Larry wasn't there, either. They drove around for a while until Hodges suddenly stopped and said, "There he is." There he was indeed, walking out of a laundromat beside his grandmother. He was carrying a basket of clothes.

Hodges quickly pulled the car up next to the laundromat, and he and Evans got out and introduced themselves. They told Larry they wanted to talk to him about coming to Indiana State. Larry demurred, saying he didn't have time to talk because he needed to install a fuel pump in his car. Larry spoke quietly and looked at the ground. Hodges thought Larry might have been a little embarrassed at how greasy his hands were.

The conversation might well have ended then and there had Larry's grandmother, Lizzie Kerns, not stepped in. "These nice men have come all this way to talk to you," she said. "The least you could do is hear what they have to say. Why don't you all come back to my house and you can visit there." Now, if there's one thing Larry Bird wasn't going to do, it was go against the wishes of his Granny Kerns. So they drove back to her house with the coaches following behind. When they got there, Larry told his grandmother that she should go into the house without him. He'd drive away and come back when the coaches were gone. But she wasn't having it. "We raised you better than that," she said. "You already told these men you'd talk to them."

Hodges and Evans followed them inside and took a seat in the living room while Granny Kerns milled about in the kitchen. Hodges did most of the talking. Having grown up in the small farming community of Zionsville in northern Indiana, he had a lot in common with Larry. They started by talking about Indiana basketball. Hodges told Bird he had played in high school against Rick Mount, a legendary Indiana ballplayer who went on to become an All-American at Purdue. Bird had played against Mount in an AAU game recently, so he knew all about him. They talked about other players around the state. Larry still wouldn't look at Hodges, but he started to relax and open up a bit. Hodges asked Larry what he had been doing. Larry told him about his work for the French Lick street department, including the garbage duty.

"Do you drive the truck?" Hodges asked.

"Nah, I just ride on the back," Larry replied with a smile.

Hodges was trying to figure out a way to steer the conversation back to Larry's recruitment without scaring him off. So he talked about his new job as an assistant coach at Indiana State and his need to find good players. Bird told Hodges he should recruit a kid in town named Kevin Carnes, the older brother of Larry's good buddy Beezer Carnes. Kevin had been the starting point guard on a team at Springs Valley that had won a sectional championship three years before. He was married and had a child, but he was still living in French Lick. "He would have been a really good player if he had gone to college," Larry said. Hodges sensed an opening.

"You know, Larry," he said, "someday they're gonna say the same thing about you if you don't go to school."

For the first time all day, Bird looked Hodges straight in the eye. He said nothing.

Some three decades later, Hodges still remembers every little detail from that first visit to French Lick. He remembers what Larry was wearing ("a white T-shirt and blue jeans"). He remembers what Granny Kerns's living room looked like ("hardwood floors, antique-ish country furniture, nothing fancy, but it was as clean as you can imagine"). He even remembers her hair color ("salt and pepper; she was a little ittybitty lady") and what she served them ("iced tea, good and sweet"). Most of all, he remembers that moment when Larry Bird looked him straight in the eye for the first time and didn't say a word. "You can tell when you've sold somebody something," Hodges says. "I knew I had hit a home run. I figured it was time to go and let that soak in."

As Hodges started to wind down the visit, Evans became more involved in the conversation. He pressed Larry on whether he wanted to go to school and play basketball. As Larry continued to put them off, Evans grew impatient. "What are you going to do, work on a garbage truck the rest of your life?" he asked.

"I don't know, it's a pretty good job," Larry said. "I like it."

By now, Hodges knew he needed to get both of them out of there. He thanked Granny Kerns, suggested to Larry that he think about it, and said good-bye. When he and Evans got back into their car, Evans figured the visit had been for naught. "We're wasting our time with this kid," he said. "Anybody who'd rather work on a garbage truck than go to college isn't smart enough to play for us."

Had Hodges agreed with that assessment, it is likely that Larry Bird would never have played college basketball, much less in the NBA. Instead, Hodges kept up his pursuit, even though his experiences recruiting out of small Indiana rural communities had taught him the odds could be long. "A number of those kids just stay down there and wilt on the vine," Hodges says. "I'm not talking about French Lick. I'm talking about southern Indiana. A hell of a lot of good players never make it out of their town."

Another complication was that Larry couldn't come to Indiana State without an official release from Indiana University. Hodges got a form, filled it out, and addressed an envelope to the Indiana University basketball office. All he needed was Bird's signature. Hodges returned to French Lick a few days later, this time without Evans, who remained skeptical. "Here was a six-nine white kid who didn't show any interest in playing college basketball. How good could he be?" Evans says. "Kentucky passed over him. Bob Knight didn't show any effort to get him when he left Indiana. We needed players, and in my view one player who didn't want to come here was not the answer."

When Hodges stepped onto Georgia Bird's front porch this time, he got a much sweeter greeting. She told him Larry was home and immediately invited him inside. This is different, Hodges thought. What Hodges didn't realize was that Georgia Bird had wanted her son to go to Indiana State all along. "Larry was pressured into going to Indiana by people in town who wanted him to play in the Big Ten," she later recalled. "I was dying to say to Bobby Knight, 'Why don't you leave him alone, he doesn't want you,' but I never did. Then, when Coach Hodges came the next year, it was like an answer to a prayer, because I knew Larry had the talent but he wasn't using it. He was hanging around here, working for the town collecting garbage and painting park benches. But Larry wanted me to tell everybody he wasn't available, and I told Coach Hodges just that."

When Hodges came through the door and sat next to Larry in Georgia's living room, he showed Larry the release form. "How did you know I was thinking about coming?" Larry asked.

"I didn't," Hodges said. "But I know this is the best thing for you, and you're smart enough to make a good decision." Hodges explained that the release didn't commit Larry to coming to Indiana State; it just gave him the option. Larry signed.

After visiting for a while, Hodges told Larry he'd be back again soon. When he got up to leave, Larry followed him outside and said he had a question. If he came to Indiana State, could Hodges get him a summer job so he could go up there right away? Hodges assured him something could be worked out.

The next time Hodges came to town was on a day Bird was supposed to play for an independent team against a group of Indiana high school all-stars. Hodges drove into French Lick and found Larry putting up some hay. Despite several hours of rigorous work under a blistering sun, Larry went out that night and scored 43 points and grabbed 25 rebounds before fouling out.

Hodges had also learned that Tony Clark, one of Larry's former teammates at Springs Valley, was a sophomore at Indiana State. So he called Clark and asked if he'd go with him to watch one of Larry's AAU games. They went to the town of Mitchell, where Clark was amazed at how much his old friend had improved. "Oh, he looked good. He was six-nine, same passer as always, just phenomenal," Clark recalls. After a few more trips, Clark sensed that Hodges's pleasant persistence was starting to pay off. "Bill had a real good personality to fit Larry," Clark says. "He had that small-town understanding of what it took to motivate him. He definitely had a caring for Larry as an individual. He wanted Larry to get a degree, and it showed."

As Hodges pressed his case for Bird to visit Terre Haute, Larry kept trying to convince Hodges to recruit his buddy Kevin Carnes instead. So Hodges invited Larry to bring Kevin with him, and he would set up a scrimmage against the Indiana State varsity. Larry, who was always up for a challenge, readily agreed. So he grabbed Carnes and Mark Bird, Larry's brother, and the three of them headed for an overnight visit to Indiana State.

When the trio arrived at the gym, they were wearing blue jeans and tennis shoes. Hodges offered to get them some basketball gear, but they declined. They were used to playing in jeans, even if they were running outdoors in the dead of summer. Hodges offered a second time to get them shorts and basketball sneakers, but they again said that's okay; they'd just as soon play in their jeans.

So Hodges assigned them a couple of teammates and told them to have fun. Though he was technically forbidden by NCAA rules from watching, Hodges stood in a corner doorway and caught the action. He was astounded. The boys from French Lick absolutely drilled his varsity, game after game after game. Even Kevin Carnes, who had played on Larry's AAU team, was struck by how easily Bird dominated the competition. "When you're from a small community, you never know how you're going to compete against people like that," Kevin Carnes says. "I mean, I was amazed. We didn't lose a game that day. That's the first time I realized he wouldn't be out of his league if he played in college."

Hodges was convinced that Carnes was good enough to play for Indiana State, too. He introduced Carnes to Bob King and showed him the on-campus housing for married students. Carnes enjoyed the visit (aside from the moment when Larry threw ice-cold water on him when he was in the shower). During a stroll around campus, Larry, Kevin, and Mark came upon the track and staged an impromptu highjumping contest. Still, Kevin was married with a child and felt that college wasn't for him.

Larry, on the other hand, was sold. He might not have been all that juiced about school, but he was very impressed that the Indiana State players stayed in Terre Haute all summer. He loved the idea of going up against quality competition every single day, something he couldn't do in French Lick. It was also critical for him to know that, unlike in Bloomington, he wouldn't be a stranger in a strange land. Though Carnes wasn't joining him, his good friend Tony Clark was already there. And Hodges was recruiting another childhood chum and former Springs Valley teammate, Danny King, from Cumberland Junior College in Tennessee.

At the end of the visit, Larry told Hodges he needed to go back to French Lick for a couple of days to get his things together, but he had decided to come to Indiana State. He had been given a second chance at a life outside of French Lick, and he wanted to take it. If he couldn't make it work, he'd have to run home again, maybe this time for good.