Even as a minor leaguer, Roger Clemens was a man on a mission

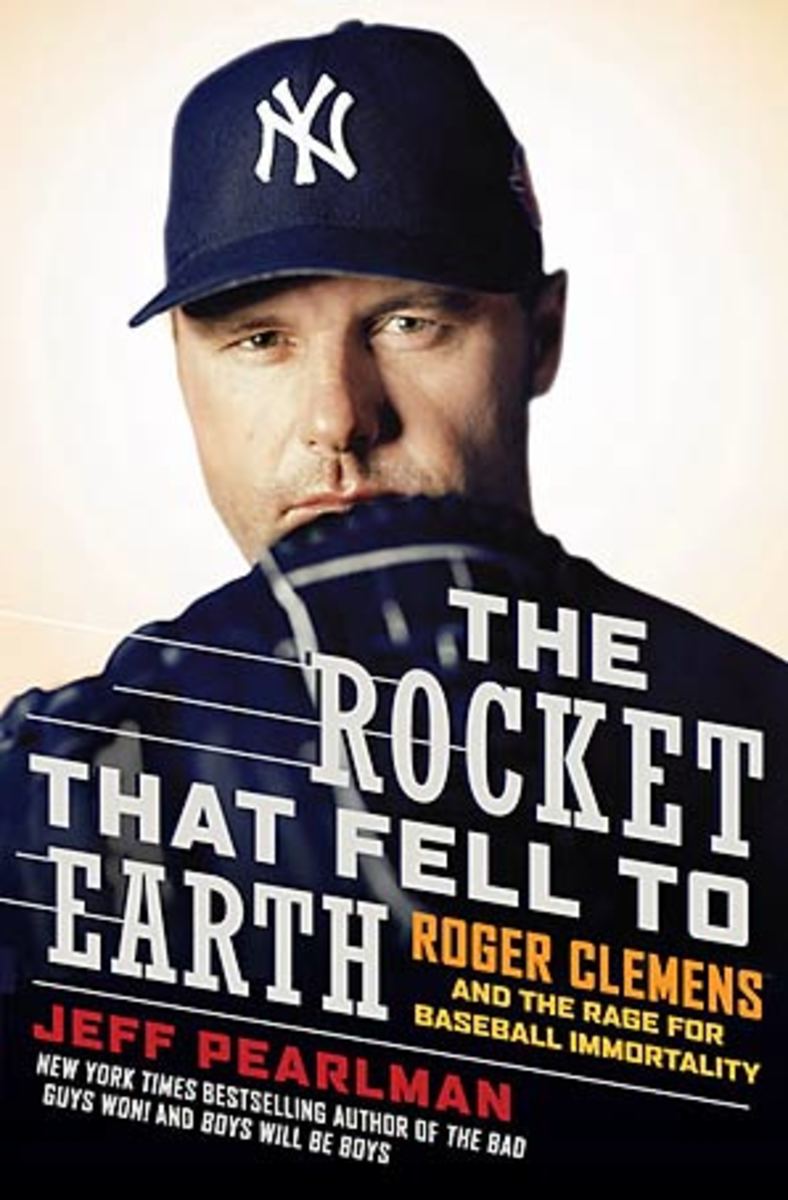

From the book, THE ROCKET THAT FELL TO EARTH: Roger Clemens and the Rage for Baseball Immortality by Jeff Pearlman. Copyright © 2009 by Jeff Pearlman. Published by arrangement with HarperCollins, LLC. All rights reserved.

* * *

In the summer of 1983, there could be no greater baseball opposites than Roger Clemens and Ronald Davis.

Having signed for $121,000 with Boston shortly after winning the College World Series with Texas, Clemens was a Red Sox bonus baby, the highly touted prospect who -- with a mid-90s fastball and Bob Gibson's snarl -- was all but guaranteed a major league future.

Having signed for $4,000 with Detroit after going undrafted out of tiny Delta State (location: Cleveland, Mississippi), Davis was a Tigers nobody, a moderately competent first baseman who -- boasting a Swiss cheese bat and Steve Balboni's swiftness -- would be lucky to attend major league spring training in his lifetime.

The only thing the two men seemed to share was geography: On a July night in 1983 both ballplayers were standing inside Chain O' Lakes Park in Winter Haven, Fla., for a Florida State League game between the Class A Lakeland Tigers and the Winter Haven Red Sox.

Up until that evening Roger Clemens was everything the Boston franchise had dreamed of. He had joined Winter Haven in late June while the team was on a road trip to Fort Lauderdale, and after spending his first day becoming acquainted with his teammates, he had thrown a brief bullpen session. The performance was one that most of Winter Haven's players still remember.

Cliché be damned, the ball seemed to explode from Clemens' right hand like some sort of nuclear weapon. With each grunt and release, Clemens unleashed a bullet that slammed into catcher Billy Joe Richardson's glove. Ooof-pop! Ooof-pop! Ooof-pop! Standing nearby were a handful of Clemens' new Winter Haven teammates, mostly lowgrade talents with thin résumés and futures selling medical supplies and teaching third grade. They were there to see the hyped new kid, to hope, in a common jealousy that runs through minor league sports, that he wasn't as good as advertised.

Damn. He was even better.

Fastballs that hit 96 mph on the radar gun. Pinpoint control. A sadistic slider. "It was beyond belief," says Pete Cappadona, a Winter Haven pitcher. "I remember talking to Tom [manager Tom Kotchman], and we just looked at each other and I said, 'He ain't gonna be here for very long.' "

Clemens pitched just four games and 29 innings for the Class A Sox, compiling a 3-1 record with a 1.24 ERA and -- most amazing -- 36 strikeouts and zero walks. "Class A pitchers walk loads of people," says Daniel Weppner, a Winter Haven reliever for a team that finished 49-84 and in last place in the Northern Division. "It's what they're supposed to do."

Following his debut start, a five- inning, nine- strikeout, 3-0 cakewalk over St. Petersburg during which he fanned the first five hitters ("Besides having my first child," says Richardson, "my greatest thrill is having caught Roger's first pro start"), teammates began chalking a K on the dugout wall every time Clemens set someone down on strikes. "That's something fans do, not players," says Mark Meleski, a Winter Haven infielder. "But he made fans out of us all."

Clemens stayed in a room with a kitchenette at the rickety Winter Haven Holiday Inn and was perpetually accompanied by a brown briefcase that contained scouting reports of opposing teams' hitters. He would eat a couple of meals with teammates at Sally's Shrimp Boat, where alligators would swim to the deck in search of food, and have an ice cream or two at Andy's Igloo. Otherwise -- yawn. "He kept to himself and was always respectful," says John Michael Roth, a Winter Haven outfielder. "You could tell he was focused on one thing, and that was moving up the ladder as quickly as possible."

Yet here Clemens stood, in the center of Chain O' Lakes Park, making his fourth start and focused on something beyond personal glory. Two days earlier, in a game against the Tigers on the road, Mike Brumley, Clemens' friend and former Texas teammate, was playing shortstop for the Sox when Lakeland rallied. With Davis on first and one out, a Tiger named Reggie Thomas hit a hard shot to Winter Haven second baseman Chris Cannizzaro, who fielded the ball cleanly and threw to Brumley. Initially thinking the ball had reached the outfield, Davis found himself hung up between sliding and not sliding.

"So I made my body roll into second, and I took Brumley out really hard and flipped him over," he says. "I certainly wasn't trying to hurt the kid."

As he jogged off the field, Davis heard the jawing from the Winter Haven dugout. "You'll get yours, you son of a bitch!" Clemens screamed. "I'll see you in two f------ days!"

Now Clemens was pitching against the Tigers, anticipating his chance for revenge. In the first inning he struck out the leadoff hitter, Chris Pittaro. He struck out the second hitter, Lorenzo Arce. He struck out the third hitter, Virgilio Silverio. In the second inning he struck out the cleanup hitter, Thomas, and the fifth hitter, Rondal Rollin. "Roger was just throwing BBs," says Cannizzaro. "They couldn't touch him." As he squatted in the on deck circle, preparing to hit, Davis thought about the warning that his manager, Ted Brazell, had issued before the game: "Watch out tonight. Clemens will be coming after you."

When Rollin was retired, Davis, a left- handed hitter, walked up to the plate, took a couple of practice cuts and dug in. Born and raised in tiny Laurel, Miss., Davis had long dreamed of escaping his small town to play professional baseball. "I loved the chance to meet the people from different countries -- the Dominicans, the Mexicans," he says. "People heard I was from Mississippi and they'd ask if we had paved roads." Though he was a good enough college player to be named a Division II All-American, Davis was more space filler than prospect. "I knew what I was," he says. "I had my limits."

As Davis looked out at Clemens, he wasn't thinking about getting beaned or having to duck or Wayne Dyer's 10 keys to self-preservation. "I just wanted a hit," he says. "The same as always."

Clemens wound up, unfolded his six- foot- four frame and let loose a fastball that traveled directly from his hand to the back of Davis' head. PUH! The sound was dull, like a fist pounding dough. The ball was thrown so hard that it ricocheted off Davis' helmet and into the stands. Davis took a couple of steps forward, wobbled, then fell to the ground like a drunkard following one last shot of Jägermeister.

When he finally rose, Davis tried charging the mound but was overcome with dizziness and dropped again. "I understood him throwing at me," says Davis. "I can respect standing up for a teammate. But he threw at my head. At my head! You don't mess with somebody's career like that."

Davis was taken to the nearby hospital. Clemens remained in the game and struck out 15 Tigers. Ed Kenney, Boston's farm director, was watching from behind home plate. He was dazzled. The kid had guts. It would be Clemens' final Class A start.

Following the game, one Winter Haven player after another approached Clemens' locker to shake his hand. He had defended a teammate -- the ultimate act of baseball decorum. "That's what you're supposed to do," says Steve Ellsworth, a Winter Haven teammate. "It speaks to what type of competitor Roger was."

Yet for a man who would go on to make a reputation off of brushing back opposing hitters, Clemens was surprisingly shaken. A couple of days after the game, Davis received a handwritten letter of apology, with Clemens (laughably) insisting that he had been aiming for the leg, not the skull.

"I never really forgave him, because I know it was 100 percent intentional," says Davis, who retired after the '84 season and now works as an electrical technician. "But, heck, I can always say I was the first professional baseball player Roger Clemens beaned."

* * *

Although Clemens would spend the first 16 years of his major league career burdened by the dreaded "He's never won the big one" label, that was -- technically -- not the case.

In 1983, Clemens won the big one.

Granted, it was an Eastern League championship with Double A New Britain.

Upon his arrival in Connecticut, Clemens entered the clubhouse of Beehive Field and was warmly greeted by Rac Slider, the New Britain manager and a man whose mannerisms must have felt familiar to the young pitcher. A 49- year-old baseball lifer, Slider had been raised in Simms, Texas, a middle-of-nowhere ranching town that taught the rugged, take-no-crap mindset that Clemens had adopted as his own. "I believed in being tough," says Slider. "You don't do your job, you have to answer to me."

Before Clemens' arrival, Slider had been briefed on what was at stake here: namely, the future of the Red Sox. Slider was not to over work Clemens. The pitcher was never to throw more than 100 pitches or enter a game in relief. Slider's job title was officially "manager," but in this case he was primarily a caretaker. Nurture the kid, teach him a few things -- and, by the grace of God, don't screw anything up.

Knowing that Clemens was being babied, it would have been easy -- expected, even -- for New Britain's other players to loathe the kid. To some extent, they did. "Roger was nice enough," says Gary Miller Jones, New Britain's second baseman. "He had a very high opinion of himself, which a lot of us didn't like. But it's hard to criticize that, because his attitude was part of the package. He believed he was a major league pitcher, even when he wasn't. Were some of us jealous? Of course we were. Some of us had been in Double A for three or four years, and this young guy's shooting through the organization. How would you feel?"

Any resentment, however, was dulled by the unassailable truth that Clemens was brilliant. For the other New Britain pitchers -- a highly regarded group that included future big leaguers Ellsworth (who had also been promoted) and Jeff Sellers -- it was surely similar to what Antonio Salieri had endured when watching the young Mozart at work. "He was a phenomenon," says Clinton Johnson, a New Britain right-hander. "His fastball was insane. His slider was sharp. He had complete command of the strike zone. I saw him throw, and I thought, 'This boy is ready for the big leagues right now.' "

"Catching Roger was as easy as drinking a glass of water," says Jeff Hall, a New Britain catcher. "You start on the black and keep going until the ump calls a ball. That was all it took. He did the rest."

As was the case in Winter Haven, Clemens largely kept to himself in New Britain, preferring a bucket filled with quarters at the local video arcade to nights out with teammates. At the tail end of an era when ballplayers lived hard and played harder, Clemens merely played hard. "He didn't drink, didn't smoke, didn't swear," says Hall. "He wasn't a loner, but he didn't buddy up to people. He was there to pitch."

In seven starts Clemens went 4-1 with a 1.38 ERA. He struck out 59 over 52 innings, walking just 12. With a 72-67 record, New Britain charged into the Eastern League playoffs intent on winning a title. "He was going to be brought to me for the final month," says Tony Torchia, manager of Triple A Pawtucket. "But we were pretty bad, and I urged the franchise to get him some Double A playoff experience. I felt there was more value in that environment, and they agreed."

The Sox faced the Reading Phillies in the best-of-three first-round series, and Slider named Clemens his opening game starter. As opposed to the riffraff he had faced at Winter Haven, Reading's lineup was stocked with future big leaguers like Juan Samuel, Darren Daulton and Jeff Stone. The Phillies were 96-44 and, had anyone cared to bet on a Double A playoff series, would have been prohibitive favorites. In a team meeting before the opener, Slider gathered his men around him. "Most of you guys will never reach the major leagues," he said. "To you, these playoffs represent your best shot at getting a ring. So don't hold back. Don't keep anything inside. Let it all out."

As Clemens warmed up to start the game, he was approached by the home plate umpire and told that his glove was illegal. Reading manager Bill Dancy had issued the complaint -- a not-especially-subtle attempt to rattle the kid. "All that writing," the ump said. "It's distracting." (While Clemens was at Texas, several female friends had sneaked into his locker and, believing the Rawlings mitt was an extra, scribbled Good luck, Goose and We love you in black shoe polish. The writing wouldn't wash off.)

Clemens agreed to switch gloves but wanted first to complete his warmups. With Slider and the New Britain bench ripping into him, the umpire lost his cool. "You change that glove when I tell you, you little f---!" he screamed. Slider charged the umpire. Clemens charged the umpire. Dancy, grinning ear to ear, was euphoric. His plan had worked -- another top prospect was about to unfold under the stress of the postseason.

Clemens, however, was no ordinary phenom. He cooled down, borrowed teammate Charlie Mitchell's glove and dominated the Phillies, holding them to one hit, one walk and no runs while striking out 13 over 10 innings in a 1-0 victory. "We couldn't hit him," says Stone. "He was throwing 97 mph with a nasty curve. He was out of our league." Afterward, Dancy sought out Clemens to shake his hand. "You," he said, "don't belong here."

New Britain defeated the Phillies in three games, and Clemens' final Double A start came eight days later, when he faced the Lynn Pirates for the Eastern League title. The Sox led the best-of-five series two games to one, and Slider was happy to give Clemens the chance to finish things off. In a game that was never close, Clemens threw a three- hitter, striking out 10 Pirates in a 6-0 rout.

Within a span of three months Clemens had won two titles. Though he had been with New Britain for less than five weeks, Clemens soaked in the postgame champagne, giddy over the completion of a memorable first season.

As if Clemens' life weren't enough of a fairy tale, in the aftermath of New Britain's championship he was pulled aside by Slider and told that the organization would like him to spend some time in Boston.

Cocksure on the mound, Clemens could be equally reticent off of it. As he tiptoed into Fenway Park on a late summer day, his eyes the size of Oreos, the kid from Butler Township, Ohio, had made it. He took in the thick grass, the rows upon rows of seats, the Green Monster. Clemens had been to the Astrodome numerous times as a teen, but this -- Fenway -- was baseball.

Entering the small, no frills Red Sox clubhouse, Clemens was flabbergasted to see that he had been issued a locker (well, he shared a stall with a batboy named Walter McDougal), with uniform number 21 dangling from a hanger. Though he was there strictly as an observer, the gesture from clubhouse man Vinnie Orlando rendered the prospect speechless. The numeral was more than mere digits to Clemens. His older brother Randy had worn number 21 throughout high school and college, and he and his wife Kathy had been married on Dec. 21, 1975. When Clemens had signed with the Red Sox he had bought his mother a ring encrusted with 21 diamonds.

In his weeklong visit to Boston, Clemens the baseball phenomenon was treated like a clubhouse boy. Few players spoke with him, acknowledged him, engaged him in so much as prolonged eye contact. During games he sat in the press box. "Back then the Red Sox veterans treated young guys like we weren't even there," says Lee Graham, an outfielder who played five games with Boston in 1983. "It was like you were a fly on the wall, and you'd better not open your mouth."

In the major leagues it was nothing special to see a guy throwing 94 mph with pinpoint control. This was the terrain of Tom Seaver and Nolan Ryan and Ron Guidry and dozens of other similarly skilled professionals. Clemens' bullpen sessions hardly raised eyebrows, but his work ethic did. With his season completed, Clemens had earned the right to kick back. Instead, he was running pole to pole in the Fenway outfield; doing situps and pushups beneath the stadium; lifting weights as the other players spent the pregame hours smoking cigarettes, playing cards and eating hoagies. "My first impression was 'This is the hardest worker I've ever seen,' " says Dave Stapleton, Boston's first baseman. "Young players come and go, and they usually don't resonate. Roger resonated."

* * *

In January 1984, while home in Houston, Roger ran into an old Spring Woods High classmate named Debbie Godfrey. Perky yet tough, with wavy light brown hair and an athletic physique, Debbie was a ballet, jazz and tap dance instructor who -- like Roger -- had been raised in the lower middle class environs of suburban Houston.

Her family lived in the rundown Victorian Village apartment complex across the street from the high school, though Debbie's optimistic confidence concealed any despondency. "We have a lot in common," Debbie once said. "We both grew up knowing hard times. My mother was divorced. We didn't have much."

Although Roger and Debbie were friendly in high school, it had been primarily a "Hi!"-and-"Bye!" relationship as they passed each other in the hallway. Debbie had dated one of Roger's baseball teammates, a kid he didn't particularly care for. Now, in the early winter of 1984, Roger and Debbie were brought back together. A mutual friend had arranged an encounter, telling Roger it was a blind date and Debbie that it was merely a gathering of long lost chums. "My first impression of Roger was 'What a tall, handsome man!' " she said. "More than that, he seemed responsible. He always did everything he said he was going to do. And he was sweet. He wanted only to talk about what I was doing. We met on the 10th. Our first kiss was on the 19th."

In Debbie, Roger found not merely a lover but a sports fanatic and workout partner. In the midst of auditioning for the Dallas Cowboys' cheerleading squad for a second straight year (she failed to survive the final cut), Debbie was obsessed with fitness and righteous eating. In Roger, Debbie found a man who held doors open and answered every one with "Yes, sir" and "Yes, ma'am." He was a kid in a giant's body, a surprisingly affectionate lug who treated his mother like a queen and placed family above all else. If there was an arrogant side to Roger, Debbie sure didn't see it. Plus, unlike the vast majority of Texas baseball players, Roger chewed tobacco but once a year, when he went on his annual hunting trip. His teeth were as white as whole milk.

On April 10, 1984, Debbie was working out when she fell and fractured her elbow. Roger asked the Red Sox whether he could fly to Houston to be with her. They denied his request, but he went anyhow. "That blew my mind," he said. "The Red Sox got sticky about it because we weren't officially engaged yet."

At age 21, Debbie considered her defining life moment to be Nov. 22, 1963, when -- as a young child -- she had been with her mother near the Texas School Book Depository in Dallas when John F. Kennedy was assassinated.

Soon, there would be two new ones. In May, after asking the permission of her mother and stepfather, Roger proposed to Debbie. By year's end, they were married.

* * *

Clemens reported to spring training in Winter Haven in February 1984 , convinced that he would make the Red Sox starting rotation. If anyone doubted his intentions they needed only to view the rear of his black GMC truck, which featured a customized Sox-21 license plate.

Like anyone coming off of two championships, a 9-2 professional record and a buffet of experts proclaiming him "The next . . ." [fill in the blank with Nolan Ryan, Bob Gibson or Tom Seaver], Clemens looked at Boston's so-so collection of returning pitchers and knew he belonged. In 1983 Boston had endured a forgettable 78-84 season. Surely manager Ralph Houk would be sold after one glimpse of Clemens' blistering stuff.

If Clemens was struck by one thing during that initial spring, it wasn't Jim Rice's power, Dwight Evans' throwing arm or Wade Boggs' bat control. It was the lack of a team fitness regimen. Having spent much of his life outrunning, outlifting and outhustling the competition, Clemens was dismayed by Houk's glaring indifference to physical conditioning. "Our workouts consisted of something like six 60-yard dashes across the outfield," he wrote in his autobiography, "and by the third week I was in worse shape than when I reported. I kept figuring there must be something else coming, so I only did a few extra sprints. Finally I realized that's all there was."

An exasperated Clemens developed his own program, drawing scorn from a handful of Red Sox veterans. With each extra sprint, each additional pushup, Clemens was putting the other players to shame.

"If anyone felt threatened, they probably needed to look in the mirror," says McDougal. "Roger did what he knew -- busted his rear."

Though his numbers were not impressive (1-2 with a 6.60 ERA), Clemens showed enough to make the big league roster. "He's got good poise -- there's no question about that," Houk said in late March. "It's not like he's 18 years old. He's been pitching against good competition for a long time." Despite the praise, the ace in training had no chance of sticking. Had the Red Sox begun the season with Clemens on the roster, he would have been eligible for arbitration after two years. What was the rush? "I knew he had a good spring, but we had some good young pitchers that year," Houk said. "I felt going down for a month wouldn't hurt him."

On March 26, one day after Clemens was charged with six runs on eight hits in three innings against Pittsburgh, Houk called the 21-year-old into his office and told him that he would begin the season at Triple A Pawtucket. "But don't get too comfortable," Houk told his despondent pitcher. "I have a feeling you won't be there for long." Clemens was upset, but he refused to show others his true emotions. After retreating to the corner of the locker room for a brief cry, he reported to Torchia, the Pawtucket manager. His new skipper was immediately impressed. "I've always had this small method to learn about a guy," says Torchia. "It was Roger's second day in minor league camp, and we were getting ready to play a spring training game in which he wasn't pitching. So I said, 'Roger, would you mind being a batboy?' "

"Sure, Skip," Clemens said. "I'd be happy to!"

"So that was his role for the afternoon," says Torchia. "And he did a helluva job. I'll never forgot that."

Any remorse over the demotion dissipated when Clemens relocated to Pawtucket, R.I., and found, to his surprise, bliss. This wasn't Winter Haven. This wasn't New Britain. This was a vibrant small city with a die hard Red Sox fan base and a nice ballpark, McCoy Stadium. Most of the team lived within walking distance of the park and after games would usually retreat to the local bar, My Brother's Pub, for beers, wings and conversation.

As he had in the two previous minor league stops, Clemens quickly adjusted to a new league. In seven games and 46 2D 3 innings with Pawtucket, he went 2-3 with a 1.93 ERA and 50 strikeouts. He struck out 11 and allowed just three hits in a 16-0 win against Syracuse. He tossed a four-hitter, fanning nine, versus Columbus. "The games Roger lost were all close," says Torchia. "With him, there was no such thing as a terrible performance."

One month into their season, the Boston Red Sox had an off day, which gave pitching coach Lee Stange the chance to drive to Pawtucket and watch Clemens start against Tidewater. At the time Boston was 13-17, and its pitching staff was in shambles.

That night, fighting sporadic rain and temperatures in the low 50s, Clemens struck out nine batters in a 3-0 loss to the Tides. It wasn't Clemens' best start for Pawtucket. "But," says Torchia, "a picture is worth a thousand words. Roger's picture was worth even more."

Following the game, Stange pulled Clemens aside. "I don't have the final say, so this isn't official," he said. "But I believe you just made your last minor league start."

The next morning, May 11, 1984, the news was official.

Roger Clemens was coming to Boston.