Stephen Strasburg Is Ready To Bring It

Over a 40-year career a major league scout of amateur talent will raise his radar gun perhaps a million times at high school and college games. And almost every time only two digits will pop up on his screen. So in the rare instance when he sees a third digit, it is like witnessing the elusive green flash that follows a perfect sunset. After Strasburg touched 101 in the first inning against UNLV, scouts behind home plate reacted with a torrent of hyperbole. Or was it hyperbole? "I've never seen anyone like him," said one. "He's a once-in-a-lifetime talent." "He doesn't need the minor leagues," added another. "He's ready for the majors right now." "The only pitcher I could even compare him to is Roger Clemens in his heyday," offered a third. "This is something you have to see to believe."

Strasburg is famous for those absurd radar-gun readings, for the friction his fingers generate when they rub off the seams, for the hiss the ball makes when it zips out of his hand. There are a handful of major leaguers who reach triple digits (Justin Verlander of the Detroit Tigers, Bobby Jenks of the Chicago White Sox, to name two), but few of them have his delicate touch. Says San Diego Padres general manager Kevin Towers, who watched Strasburg in an intrasquad game this season, "He was dominating, as dominating as anyone I've seen. He really has no flaws. You see guys throw in the high 90s, but they usually have no idea where it's going. He can throw in the high 90s comfortably and locate it." Strasburg fanned 23 batters in a game last season, and at week's end he was 4-0 with a 1.57 ERA, but his most startling stat may be his career strikeout-to-walk ratio: 254 to 38, in 168 2/3 innings.

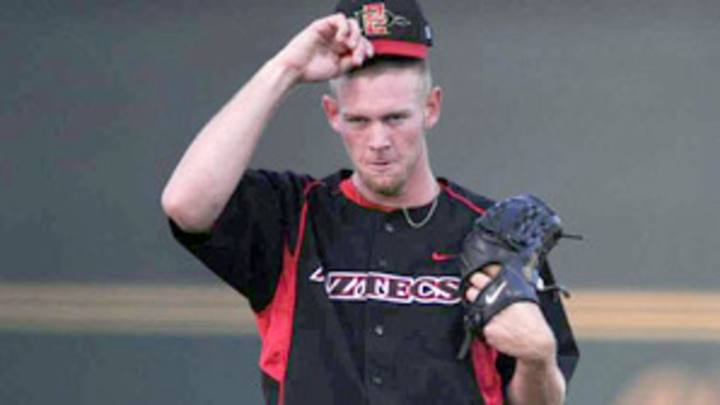

Strasburg cuts a menacing figure on the mound -- 6' 4", 220 pounds, in a black hat, black jersey, black pants, black spikes and bright-red stirrups showing over his calves. He has piercing powder-blue eyes, long blond sideburns and arms that nearly reach his kneecaps. At the top of his delivery he turns his left hip slightly toward third base, as if pulling back a bow and arrow, and then unloads with a high three-quarter release. "It's so smooth," says Aztecs pitching coach Rusty Filter, "it doesn't look like he's throwing as hard as he is." Strasburg has two fastballs, a riding four-seamer that has been clocked at 102 and a sinking two-seamer that tops out only in the mid-90s. That sort of heat can make good hitters look slow; Strasburg's sweeping slider can make them look silly. "We were actually sitting on the fastball," says UNLV designated hitter Ryan Thornton. "I know that sounds crazy, sitting on a pitch that's 100 miles an hour. But it just shows you how tough his slider is."

Strasburg is the consensus No. 1 pick in this year's draft -- if the Washington Nationals don't take him, they might get chased back to Montreal -- but he is almost as unaffected by status as his coach, former Padres star Tony Gwynn. Strasburg was the only collegian on the U.S. Olympic team last summer, but when he got the invitation, he assumed he was just going to be a practice player, not the starter of a semifinal game against Cuba. He has declined to take out an insurance policy on himself, and against UNLV he slid into first base to make a putout, tweaking his hamstring. After San Diego State home games he does fieldwork with his teammates, sweeping dirt off the mound and using his hands to pack it with wet clay. "I'm just a college kid," says Strasburg, albeit one who is advised by superagent Scott Boras.

In the modern sports world it is hard to find a phenom who comes out of nowhere. Professional scouting is too organized, amateur athletics too sophisticated. But Strasburg won just one game as a junior at West Hills High outside San Diego, went undrafted after his senior year and failed to impress Gwynn. "To me, he didn't have a lot of confidence," Gwynn recalls. Strasburg was 250 pounds, had never lifted a weight in his life, and after practice every day went to Estrada's Taco Shop and scarfed down a California burrito, packed with carne asada, and french fries. He could throw 90, but he was so out of shape that his knees would occasionally buckle during games, forcing coaches to help him off the field. "He would just collapse," says his high school coach, Scott Hopgood. "It was scary. His knees couldn't support his weight." When scouts asked Hopgood to name his best pitcher, he pointed them to a polished lefty named Aaron Richardson.

"I know everybody now is asking, 'How did you miss on Stephen Strasburg in high school?' " says a major league scout. "But we didn't miss. He was soft in every way." Strasburg would bark at infielders after errors and at umpires after bad calls. If he gave up a couple of hits and the opposing dugout started to chirp, he had a tendency to overthrow his fastball, which would then flatten out and get smacked even harder. "I told scouts not to draft me," Strasburg says. "I wasn't ready."

Filter saw those radar-gun readings, that swimmer's wingspan, and persuaded Gwynn to take him. During Strasburg's first night on campus it became clear he was a little different. He was living in a dorm at University Towers and was asleep at 10:30 p.m. when his roommate stumbled in with five female students. Strasburg was aghast. A few days later he moved in with his mother and grandmother, who share a nearby house. Then by the end of Strasburg's second week, when conditioning began, he was ready to drop out of school altogether. "I was this close," he says, holding his thumb next to his index finger. "I was going to find a job. We have a Home Depot and a Lowe's near our house."

The man responsible for almost driving Strasburg away, and then for whipping him into shape, is Dave Ohton, the Aztecs' barrel-chested strength coach. When Marshall Faulk was playing football at the school, Ohton called him "a visitor" because he was so extraordinarily gifted and physically mature, he had to be an alien life force. Strasburg was no visitor. When the baseball team convened in September 2007 for preseason workouts on the football field, Ohton had the players warm up by running from the goal line to the 50 and back. Strasburg could not get through four sprints without vomiting. "Is there something wrong with you?" Ohton asked. "Do you have a medical condition?"

Strasburg bowed his head, his chubby cheeks a bright red. "Just out of shape," he said. Ohton nicknamed him Slothburg, which he later shortened to Sloth. "I demoralized this young man," Ohton says. "I didn't even want him around the other players. I had never seen a college athlete who was as far behind as he was. I didn't think it was possible to be that bad." After two weeks of conditioning and purging Strasburg passed Ohton on the stairs in the weight room. "I appreciate your staying on top of me," Strasburg said. Ohton paused at the top of the staircase. "Sloth," he said, "you really should consider quitting. You're not going to make it."

Recalling that exchange, Ohton shakes his head. "Well," he says, "I guess he shoved those words up my ass." Strasburg thought about the scouts who had ignored him, the strength coach who had slighted him, and decided he was not ready to mix paint at Home Depot just yet. Not only did Strasburg stick with Ohton's conditioning program, but he also added Bikram yoga classes to improve his concentration and flexibility. His mother, Kathleen Swett, a retired dietitian, taught him how to cook his own burritos. When Strasburg arrived at San Diego State, he could do one bench press at 115 pounds; now he can do 21 reps at 135 pounds. He leg-pressed 560 pounds; now he leg-presses 1,200 pounds. His vertical jump was 24 inches; now it is 35 inches. His gut turned into a six-pack, then into an eight-pack. "He'd come in the door and lift up his shirt and say, 'Check it out,' " says Swett.

Of course, given baseball's recent history, all radical changes in body type are viewed with suspicion. But Strasburg did not get bigger. He got leaner. "I take a lot of pride in doing this naturally," he says. "It's hard work that's paying off -- not cheating the game."

As the pounds dropped, the velocity rose. He went from the low 90s in the fall of his freshman year to the mid-90s in the spring. He was clocked at 98 in the summer with the Torrington (Conn.) Twisters of the New England Collegiate Baseball League. In the fall of his sophomore year he hit 100 for the first time, and by the fall of his junior year he was at 101. Such spikes are unusual, but not unheard of. Chicago Cubs righthander Rich Harden went from 95 to 100 in one year -- between 2002 and '03, when he was in the A's minor league system -- due mostly to better conditioning and a couple of changes to his mechanics. "At that age a lot of people are still maturing physically," says Rick Peterson, who was Harden's pitching coach with the A's. "You might have a guy who was shaving once a week and is now shaving every day." Indeed, Strasburg said he only started getting facial hair in his senior year of high school. Now he has a goatee.

Given that he is only 20, Strasburg may have a couple of more miles per hour left in his right arm, but nobody with his best interests at heart wants to see him throw any harder. "It's better to throw 105 than 95, but it's better to throw 95 and be on the field than be in a trainer's room telling people you used to throw 105," says Glenn Fleisig, a research director at American Sports Medicine Institute in Birmingham who studies pitching. "The harder you throw, the more success you have, but you're pushing your body to higher demand." Strasburg is already stretching his limits. A person throwing a 90-mph fastball rotates his arm at a rate of 22 times per second. The more rotations, the more strain. As Stephen's father, Jim, a real estate developer, puts it, "I'm hoping he's maxed out." No one understands better than Gwynn what's at stake. He only uses Strasburg once a week and limits him to about 115 pitches. "I won't let him leave his arm here," Gwynn says.

Recession or not, assuming Strasburg is represented by Boras, he should clear $10 million when he is drafted in June, and he could conceivably be in the majors by September. The San Diego area has produced some pitching treasures in the past decade -- Barry Zito, Aaron Harang, Mark Prior, Cole Hamels and Joel Zumaya -- none of whom landed with their hometown team. Missing out on this one would sting the Padres even more. When Strasburg turned two, he wore a Padres helmet and Gwynn wristbands to his birthday party, where he was presented with a Gwynn poster. Two years ago, when Gwynn was inducted into the Hall of Fame, Strasburg took a day off from summer ball to be at the ceremony in Cooperstown, N.Y. His favorite player is San Diego ace Jake Peavy, and after beating UNLV, he wore a Padres hat while signing autographs. If the Padres had lost four more games last season, they would have the first pick and could snag Strasburg. Instead, they pick third and have to hope that the Nationals and the Seattle Mariners get spooked by Boras. "A lot of things can happen before the draft," says Washington G.M. Mike Rizzo. "There is a chance of injury. Other players come to the forefront. But we are scouting him diligently. He is a very impressive package."

The scouts only have one question left: How might Strasburg cope with failure in the big leagues? Will he bark at an infielder or scream at an umpire or overthrow his fastball? When Strasburg has given up hits -- which isn't often, considering he had whiffed 74 batters in 34 1/3 innings through Sunday -- he usually just lashes out at himself, and he does it in the dugout rather than on the mound. That high school kid with the chubby cheeks and rabbit ears is gone, replaced by the best amateur pitcher in the country and perhaps one of the best ever, with a 102-mph fastball and so much else. At San Diego State, there's a name for a person like this.

Visitor.