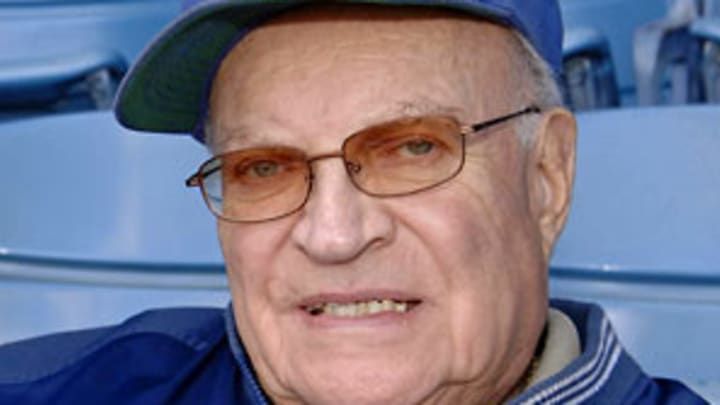

Remembering one of baseball's true characters, Arthur Richman

Arthur Richman never remembered my name.

Never.

I would see him at Yankee Stadium once or twice a year, almost always on the infield during stretching or BP. I'd walk up, tap him on the shoulder and say, "Arthur, I'm Jeff Pearlman.""Jeff who?""Jeff Pearlman. I write for Sports Illustrated.""Jeff Pearlman?""Yes, Jeff Pearlman. We've spoken before.""What was your name?""Jeff Pearlman.""And what have we spoken about?""Shawn Green."

Without fail, Richman, a short wrinkly man with a scratchy voice, would immediately step back and smile. "Shawnie Green?" he'd say. "Let me tell you about Shawnie Green. I told George [Steinbrenner] years ago that we need to sign this Jewish kid from Toronto named Shawnie Green; that the fans in New York would love him because he's Jewish and handsome and ..."

I heard the story once. Twice. Three times. I loved that story -- loved all the stories Arthur Richman, Steinbrenner's longtime special assistant, pulled out from beneath the dust and mildew of his 40-plus years in the game. Yes, the tales could go on and on and on and on. And yes, depending on the day, he would tell the same one repeatedly, whether you asked or not.

But listening to Richman, who died Wednesday at age 83, was never a chore. It was akin to sitting at a table with your Jewish grandparents, hearing them kibitz on about Henry Schwartz, the accountant who plays a mean hand of Canasta, or how the early bird special at Guggenheimer's Cafeteria isn't quite what it used to be. There was a comforting orneriness to Richman; a genuineness that, in this corporate-dominated era of professional sports, is woefully hard to come by. As Jack Curry perfectly wrote in yesterday's New York Times, "to know Richman was to know a one-of-a-kind character, a man who groused about almost everything, who never stopped yammering about money and who seemed to know everyone."

A copy boy with The New York Daily Mirror from 1942 through 1963, Richman -- who grew up a diehard St. Louis Browns fan -- was hired by the New York Mets in 1964 and proceeded to work as an executive with the ballclub for 25 years. It was during one of his final seasons with the Amazin's that Richman, at the time the team's traveling secretary, fell into one of his myriad Forrest Gump moments. After the ball went through Bill Buckner's legs in Game 6 of the 1986 World Series, Richman popped his head into the umpire's locker room, where he was greeted warmly by Ed Montague, who had spent the evening working right field.

Montague extended his hand, which held a soiled baseball. "What's that?" Richman asked.

"It's the last ball of the game," he said. "You're with the Mets. Go get Mookie Wilson to sign it, and you'll have something to treasure."

Shortly thereafter. Wilson signed the ball: "To Arthur: This is the ball that won it. Mookie Wilson."

The baseball sat on a shelf in Richman's apartment for years until, in 1992, actor Charlie Sheen paid $93,500 to purchase it. Richman donated the entire sum to charity.

Richman left the Mets three seasons later to join the cross-town Yankees. Although his main task often seemed, simply, to keep people happy and entertained (which he did very well), he also played a major role in one of the most important decisions in franchise history. Following the 1995 season, as Steinbrenner sought out a managerial replacement for Buck Showalter, Richman all but begged the Boss to take a shot on Joe Torre.

Steinbrenner's reaction was simple: Why would anyone want a retread like Joe Torre? But Richman was insistent. Torre was a winner, he swore; a communicator; a champion.

The results speak for themselves.

Approximately 200 people turned out for Richman's funeral yesterday at New York's Riverside Memorial Chapel, ranging from Lee Mazzilli and Buddy Harrelson to Ralph Branca and Phil Linz. They all had stories to tell about the mensch with the boatload of anecdotes and the uncommon vivaciousness.

Sadly, no one there was telling the story of Shawnie Green.