Hard-working Jordan left quite an impression on his Barons cohorts

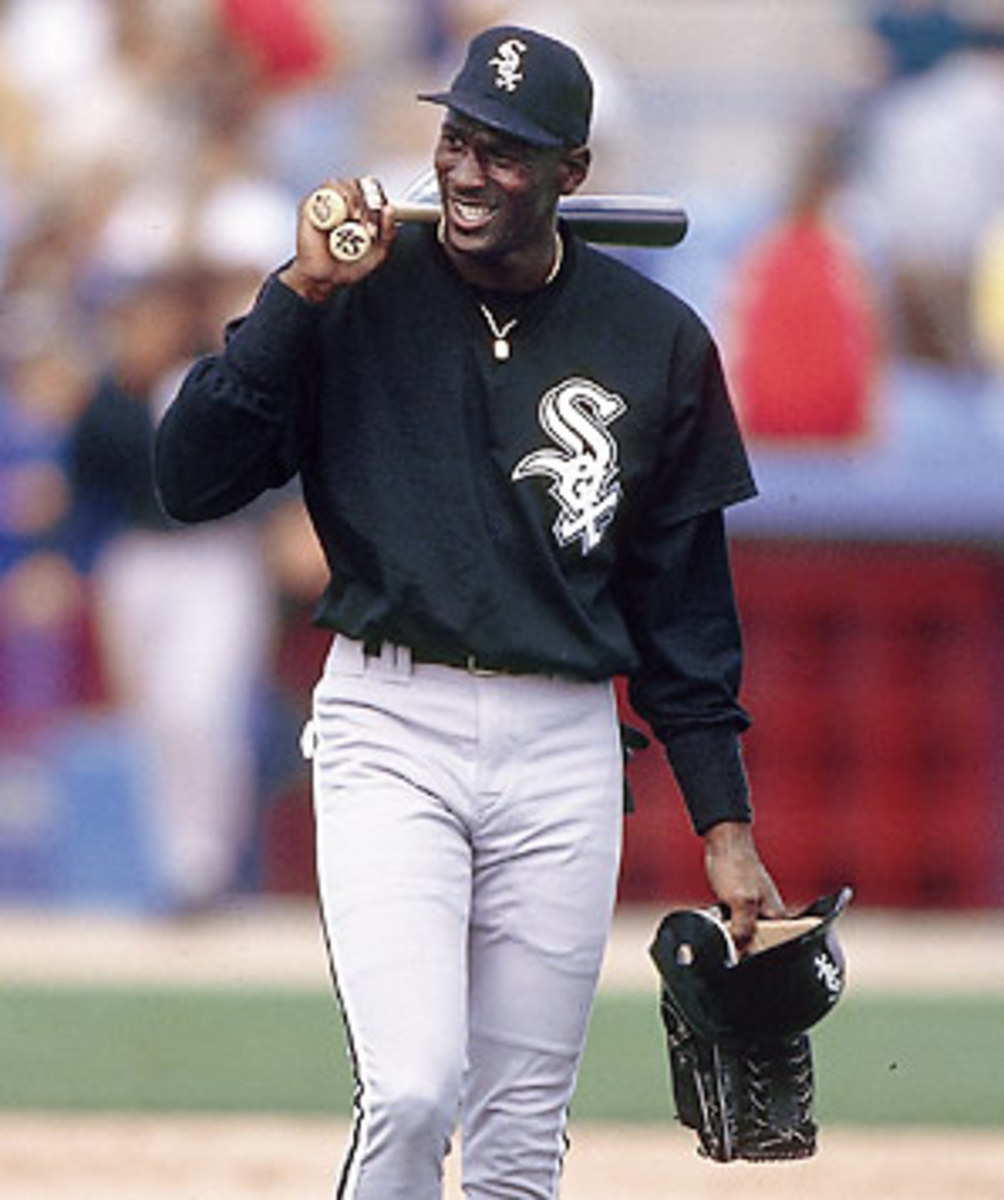

It was Tom Cruise doing dinner theater, Chris Rock performing at open-mike night and Justin Timberlake singing in the church choir. And yet it was none of those things, because when Michael Jordan announced in February 1994, just weeks before his 31st birthday, that he would attempt a career as a baseball player, it was a move so unheard of, so controversial, so odd, there was almost nothing with which to compare it. The greatest basketball player who ever lived, and one of the most famous people on the planet, was opting for a completely different outlet for his competitive fire.

For Jordan, it would be a chance to try something new, pursue a long-lost ambition and perhaps find a different way to deal with his father's recent murder. For the mostly anonymous people suddenly sucked into his orbit, it became a year unlike any they had experienced before, or since. Jonathan Nelson is now the general manager of the Birmingham Barons, but at the time he was entering his first full season with the club. And thinking back, Nelson puts it best: "It was like that REM song: the end of the world as we know it."

Almost overnight, the Barons, for who Jordan played his first game on April 8, 1994, became a staple in SportsCenter highlights. Birmingham and the other small towns of the Southern League -- like Zebulon, N.C., Greenville, S.C., and Huntsville, Ala. -- became destination stops for tourists (and even a few celebrities) all summer.

"We played in front of packed houses all year long," says Glenn DiSarcina, a shortstop on the '94 Barons and the brother of ex-big leaguer Gary DiSarcina. "We'd pull up to a stadium at 2 p.m. and there would be lines out the door to buy tickets. But they weren't true baseball fans. If a pitcher had a no-hitter going in the seventh inning and Jordan made the last out, fans would get up to leave because they knew it was his last at-bat. We couldn't believe it."

That was the common sentiment throughout Jordan's one year of beating the bushes. With his longtime fame, Jordan was fully acclimated to the circus that accompanied his every movement, but it was a new experience for everyone else unaccustomed to watching a teammate schedule a Gatorade commercial shoot around a ball game. Terry Francona, now the Boston Red Sox manager, but at the time the Barons manager, says the craziness began even before Jordan arrived in Birmingham. "We were told about it in the trailer at a 7 a.m. meeting. I was half asleep. It didn't dawn on me yet the magnitude of his life and how much people cared about him. By the time we got outside the trailer people already knew [he was coming]. I remember thinking, 'That's interesting.' "

Even dinners out required special planning. "We would go into restaurants after games and we'd have someone reserve a spot for us because we couldn't just go somewhere with him because it would be a mob scene," says DiSarcina. "The whole place would just be staring at him, like he was a rare zoo animal."

DiSarcina and his teammates sympathized with their new teammate over his fishbowl existence, but they had fun with it, too. "A couple times we would pull into a McDonald's at 11 or midnight and walk in with 25 guys, one of them being Michael Jordan, who was the face of McDonald's at the time," says DiSarcina. "He'd order a Big Mac and people would just stop in their tracks. People were totally amazed. We'd always say, Let's wait and see the reaction when he walked into a room."

Perhaps Jordan's greatest accomplishment that season was the ease with which he assimilated himself into the clubhouse, even as everyone around him struggled to give him his space. "I was amazed at the way he handled things," Francona says. "[Acting like a superstar] is not what he was about. He tried hard, was a good teammate who respected the game and respected other players."

Jordan didn't want the circus. He wanted to be one of the guys. "It was so hard because the public and the media wanted more, they wanted the NBA superstar, they wanted the entourage, the Hollywood stuff, but that's not what he wanted," says Curt Bloom, the team's play-by-play man. "He wanted to be a big-league ballplayer."

DiSarcina echoes that sentiment. "I thought he was just going to hang around and not take it seriously, but he always did," says DiSarcina. "Even though he wasn't a baseball player, he was a great role model."

He was not, however, a great baseball player. Jordan struggled to a .202/.289/.266 hitting line with just three home runs, and his struggles led to the infamous SI cover of a flailing Jordan under the headline Bag It, Michael: Jordan and the White Sox are embarrassing baseball. "It felt like everybody wanted to be his coach," says Francona. "He had a lot to learn as a baseball player and he openly admitted that. People were really critical of him, but he stole 30 bases and drove in [51] runs. It was hard for him, but he tried hard to get better."

At first, teammates marveled at Jordan's seemingly mediocre baseball skills. "But he improved dramatically, he was turning on fastballs at the end of the year," says DiSarcina. "If he came out as an 18-year-old I didn't have any question that he would make the big leagues -- the work ethic, the hand-eye coordination. It was just a little too late for him."

Jordan's struggles, however, made his rare successes all the more thrilling for those who knew him as a superior athlete. Despite his 6-foot-6 frame, he never showed much power at the plate; as the season wore on, people began to wonder if he would ever hit a home run. "That first home run was an incredible moment because we knew how hard he had worked to be successful and try to compete," Bloom says. "As he was coming around third base he pointed to the sky and that was for his father, I believe that was his father's birthday. He had hit the ball hard to the wall two or three times that night, and I remember thinking, 'Can he really do this?,' and he finally did.

"He came upstairs and did the postgame show just as if he was anyone else. Put the headphones on, and the difference was there was a bodyguard and a policeman."

His accompanying protection was only one indication of Jordan's fame, but signs of his largesse were everywhere. "I especially remember how well he treated any of our Chicago-area baseball players and their friends and family, who of course idolized him," says Bloom. "He would go into our waiting area, meet them, shake their hands, sign autographs." Jordan also supplied his teammates with brand new Air Jordans, and famously upgraded the team's bus to include a couch and table to make their lengthy bus rides just a little smoother.

"There were certain moments that were of awe," says Nelson, who said daily Jordan sightings could still shock even those who were supposed to be used to it. "There was one time we were having daily meetings in the GMs office and he parks at the end of the parking lot and just comes strolling by with his equipment bag over his shoulder and waves and we all went, 'Wow.' [He] brought everything to a different level in every sense of the word."

Jordan would join teammates and staff for games of ping-pong or pool, and Nelson remembers seeing him playing Yahtzee with Francona in the manager's office. But there was one game, of course, that everyone still wanted to see him play. Try as he might, Jordan could not change the fact that he was, at heart, a basketball player, and a pretty darn good one at that. His talent and love for the game never wavered during his sabbatical as a Baron. On several occasions Jordan would join the Barons for their semi-regular pick-up games, bringing his all-world talent, his world-renowned competitiveness and, as always, his wagging tongue. "There was a lot of trash-talking going on," said DiSarcina. "He was always going half-speed, but there were times he'd turn it on and let us know who he was."

One such occasion came during an August afternoon on a since-abandoned court at a Birmingham apartment complex. If the Porsche he arrived in didn't give him away at first, the spectacular talent that had made him one of the world's most famous human beings soon would. On the first possession, Bloom, partaking in a moment he said he wanted to "freeze forever," moved over to set a pick on Jordan's man, 35 feet from the basket. "CB, I don't need that," said Jordan. With that, Jordan pulled up on the spot and unleashed the same picture-perfect jump shot that to him was neither rare nor remarkable. To the mere mortals who were getting to see it up close and personal, it was something they'd never forget.

Swish.

After all, basketball, not baseball, always was Michael Jordan's game.