With Kalas' death, Phillies lose their voice -- and a true trademark

In a manner of speaking, there have been three emblems of the Phillies in the free-agency era: the team's over-the-top mascot, the Phillie Phanatic; the too-cool Hall of Fame third baseman, Mike Schmidt; and the voice of the Phillies over thousands of games, Harry Kalas, who was both uber-excitable and uber-cool. He died on Monday at age 73, found unconscious in the Washington Nationals' broadcast booth.

What a voice, a Midwestern baritone rendered deeper by so many cigarettes and late nights at hotel bars. He started with the Phillies in 1971 and players trusted him with their private lives and their baseball fears. He was a vault. On the air, it was all baseball, balls and strikes and looking ahead to the next inning. Not the torrent of words that pollutes so many modern broadcasts. Just enough. He took three seconds to say "Michael Jack Schmidt" so that you could feel the awe. Michael Jack Schmidt could do things that you and I and Harry himself could not do. He might as well have been saying, "Jesus, Joseph and Mary." Baseball was his church.

In the hot Philadelphia summers, in the days before cable, you'd hear Harry on transistor radios and car radios and from the top shelves of corner bars. He was so not modern, yet exuded more cool than almost anybody. He was never flustered. He was a straight man for Richie Ashburn in the many years they worked the broadcast booth together but was never the butt of jokes.

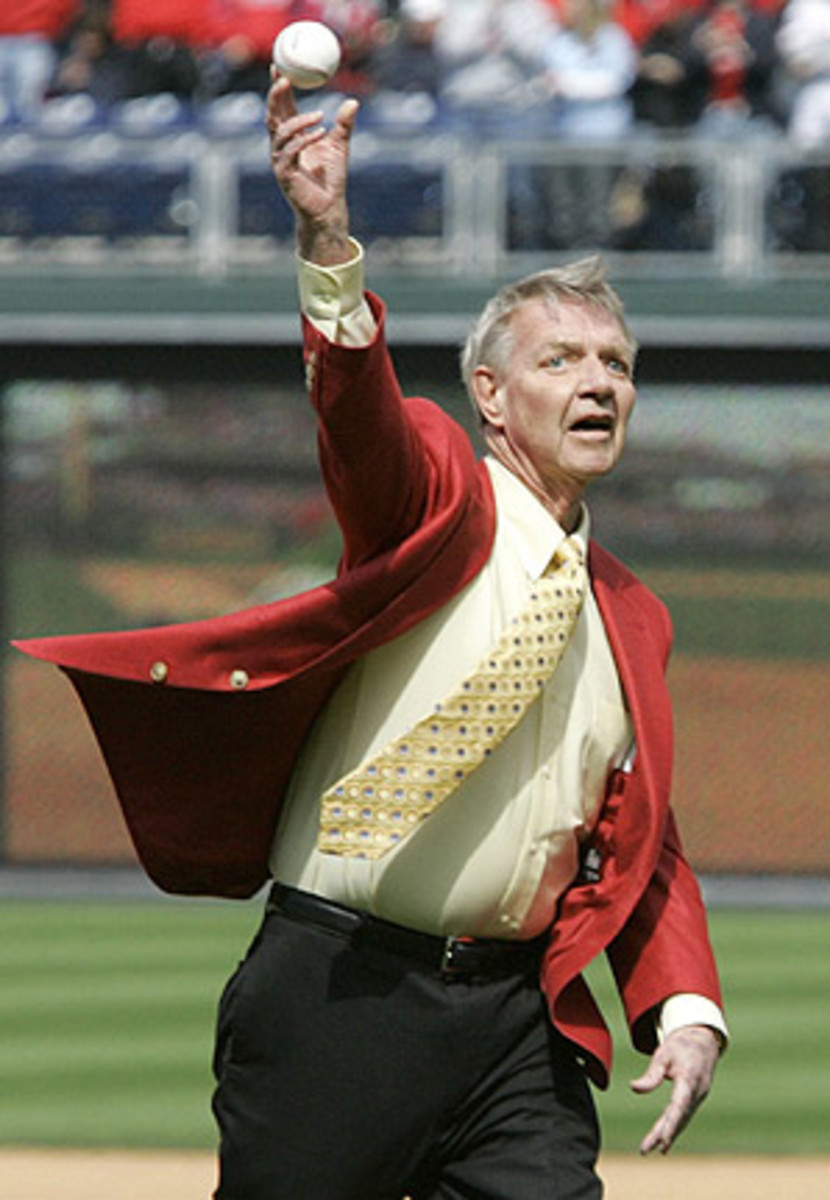

He wore Sans-a-belt trousers long after they had left the scene and came to work way early and always in a sport coat. He knew how to use the stat sheets judiciously. He once said that, while broadcasting, "I think of the shut-ins, an old lady somewhere who would like to come to the game but can't get out of her apartment."

You'd have thought Harry would go on forever, and of course his most famous calls will. You likely know his work in football, the college game and the pro game and in commercials. What a gift, to wake up every morning and have that voice. But it wasn't just the voice. His voice connected generations of Philadelphians to summer, to an unhurried passage of time, to the thrill of the comeback, to the casual boredom of another .475 team, to the thrill of victory. Anybody can say, "Strike three, stuck him out." But say it with meaning, that's a whole 'nother thing. "The World Champion Philadelphia Phillies." He wasn't saying those words for himself. He was saying them for us. He knew the fan suffers, through wins and losses and life itself. Baseball's a valve. Harry the K got that as well as anybody. He wasn't trying to impress his listeners. He was -- in the manner of another Midwesterner, Johnny Carson -- trying to give us a break from the rest of our lives. And he did.