Hit in the Head

From the forthcoming book HEART OF THE GAME: LIFE, DEATH AND MERCY IN MINOR LEAGUE AMERICA, by S.L. Price. Copyright © 2009 by S.L. Price. To be published on May 12, 2009 by Ecco, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.

This story appears in the April 20, 2009, issue of Sports Illustrated.

Around the beginning of February 2007, as the Cleveland Indians' staff was preparing to leave for spring training, team vice president Bob DiBiasio picked up the ringing phone in his office at Jacobs Field. "You've got to get down here," said Jim Goldwire of the team's operations department. "You won't believe what we just found."

DiBiasio rode an elevator down to the stadium's clubhouse level and walked to a storage room that's known as "the promotional warehouse," a dumping ground for bats, baseball caps, bobblehead dolls and other begrimed giveaways from years past. Goldwire and the head of the mail room, Steve Walters, led DiBiasio to one of the piles. They shoved aside a bunch of CC Sabathia hand puppets, brushed the dirt off a wood crate and removed the top. There it was -- huge, darkened by oxidation, nearly unreadable. "You've got to be kidding," DiBiasio said.

After he joined the club in 1979, DiBiasio received occasional calls from old-timers looking for a four-by-three-foot, 245-pound bronze plaque dedicated to the late Indians shortstop Ray Chapman. The callers said it had hung in League Park in the '20s, then in Municipal Stadium just after the team moved there in '46. DiBiasio asked around. Nobody in the organization had any memory of the plaque. "I've never seen it," DiBiasio would tell the callers. "We've looked. We don't know what you're talking about." Eventually the calls stopped.

Now, after more than 50 years lost, Ray Chapman's memorial was found. Because of the decay, you couldn't see the two-foot-long bat with the glove dangling from it, or the eulogy embossed along the bottom: HE LIVES IN THE HEARTS OF ALL WHO KNEW HIM. In the ensuing weeks, as the plaque's lettering was sandblasted and polished, all those involved in its restoration took pride in rescuing a vital piece of baseball's past. It didn't matter that it marked one of the game's darkest moments.

Chapman, after all, was the most famous example of the damage a thrown or batted baseball can do. On Aug. 16, 1920, the popular ballplayer -- 29 years old, newly married, mulling retirement -- was hit in the left temple by a fastball fired by Yankees pitcher Carl Mays. He was carried off the field at New York's Polo Grounds and died the next morning, the first and last player ever killed on a major league diamond.

The Indians would honor the man they called Chappie by winning their first World Series that year, and some good would come to the sport in response to his death: Because Mays was suspected of having doctored the ball, professional baseball banned the spitball and began requiring umpires to monitor balls and replace dirty ones. Chapman's name was invoked over the ensuing decades whenever baseball suffered other scares.

And they weren't rare. According to researcher Bob Gorman -- who this year published, along with his colleague David Weeks, the definitive account of baseball fatalities, Death at the Ballpark -- nine minor leaguers and 111 amateur baseball players as young as eight years old have died as a result of beanings since 1887. More than 90 other players were killed either by pitches that hit other parts of their bodies, usually the chest, or by balls thrown by other fielders. The last pro beaning fatality occurred in June 1951, when Dothan (Ala.) Browns outfielder Ottis Johnson took a pitch by the Headland Dixie Runners' Jack Clifton in the temple, fell unconscious and expired eight days later. Later that month a catcher for the Twin Falls (Idaho) Cowboys, Richard Conway, was killed during fielding practice by a throw that hit him just below the heart.

Among those who survived injuries from thrown or batted balls were some of the best players on the field. In 1957 Indians left-hander Herb Score, who struck out a total of 508 batters in his first two seasons (tops in the American League), was nearly blinded when a liner by the Yankees' Gil McDougald hit him in the right eye. Score's retina was damaged, and he never came close to dominating again. In July 1962 Twins pitcher and 16-time Gold Glove winner Jim Kaat lost three front teeth to a one-hopper by the Tigers' Bubba Morton. Legend has it that after Kaat cleaned up his bloodied mouth and wiped bits of tooth off his glove, he went to a party and responded to his host's startled look by saying, "I was invited, wasn't I?"

Still, nothing matched Ray Chapman for pathos until Aug. 18, 1967, when the left cheekbone of Red Sox right fielder Tony Conigliaro was pulverized by a rising fastball from the right hand of Angels pitcher Jack Hamilton. Before that night Conigliaro seemed on a sure path to the Hall of Fame: He had homered in his first Fenway Park at bat, in 1964; hit 32 homers in his second season to become, at 20, the youngest home run champ in American League history; and become, at 22, the youngest player ever to reach 100 career home runs. Against Hamilton, Conigliaro was wearing a batting helmet, but not one with a protective earflap, and on impact the ball felt as if, he later said, it would "go in one side of my head and come out the other."

By the time Conigliaro hit the dirt his left eye was purple and swollen to the size of a handball. The retina was permanently damaged; two inches higher, a doctor would later tell him, and he would've been dead. "His whole face was swelling up, blood rushing in there," says Bill Valentine, the home plate umpire that day. "When he hit the ground his eye was completely shut. It was unbelievable."

Hamilton was known for his spitball, and Conigliaro later maintained that the ball had moved unlike any legal pitch. But Hamilton, who had never hit anyone in the head before, has always said that he wasn't throwing at Conigliaro or using his spitter; he blames the shadows and his own incompetence. "The pitch got away from me, in the middle of the afternoon," he says. He tried visiting Conigliaro in the hospital that night but was told only family members could do so. The two men never spoke.

After the incident Conigliaro had some sweet moments -- Comeback Player of the Year in 1969, 36 homers in '70 -- but his eyesight deteriorated. He was traded to the Angels in 1971 and soon retired, came back briefly in '75 and then retired for good. But the black cloud over him never quite lifted. In 1982 he was in Boston interviewing for a Red Sox broadcasting job when he suffered a heart attack, then a coma-inducing stroke. He spent the next eight years in a vegetative state until dying in 1990, at age 45.

Bo McLaughlin can speak matter-of-factly, even laugh a bit, about the night in 1981 when a batted ball ruined his face. He has a tape of the game, and every once in a while at parties he pops it in to liven things up. "You could hear the bones break [through] the microphone hanging from the press box," he says. But in the months immediately following the accident, McLaughlin had little desire to watch baseball, much less play it. The first day he set out for a ball field to work out, he jumped into the front seat of his car, put the keys in the ignition and sat a few minutes before walking back into his house. He tried again the next day, making it out of the driveway and around the block before returning home. On the third day he made it to the field and was able to play catch despite the doubt racking his mind. Do I want to do this? Do I want to put my life out there?

It was a wonder he was even walking. On May 26 of that year, McLaughlin, a relief pitcher for the A's, had started the eighth inning of a losing effort against the White Sox. He got the first two batters out, then threw a 91-mph sinker to Harold Baines, Chicago's second-year right fielder. Baines couldn't have hit it better. The ball blasted off his bat at 104 mph, dipping and rising like a knuckleball. McLaughlin, all 6' 5" of him, rose out of his follow-through to catch it. "Sinker down and away?" Baines says. "That's where I'm supposed to hit the ball: back up the middle. Unfortunately his face was in the way."

The ball shattered McLaughlin's left cheekbone, broke his eye socket in five places and fractured his jaw and nose, spinning him around so that he got a full view of the center fielder before falling on his back. He vomited five dugout towels' worth of blood and went into shock. "That," says Jackie Moore, the Oakland third base coach at the time, "was as bad as I've ever seen."

Doctors at Oakland's Merritt Hospital weren't sure McLaughlin would survive the night. It took two surgeries to wire his cheekbone and left eye socket. For Baines, meanwhile, speaking with McLaughlin by phone in the ensuing days did little to ease his mind. Baines had been hitting over .300 that month, but he immediately fell into a slump -- 6 for 42, .143 -- that ended only when the major league players went on strike 16 days after the accident.

McLaughlin was 27 at the time. A six-year veteran who'd spent most of his career in the bullpen for the Astros and then the A's, winning 10 games and losing 20, he was nobody's idea of special. He came back to pitch for Oakland that September, but the muscles and nerves in his cheek hadn't healed and he couldn't get in shape; when he ran it felt as if a hockey puck were sliding around beneath the skin. He appeared in four games, in which he seemed to be fine until he got two outs; then he fell apart. On Sept. 20 in Chicago he started the eighth inning, got two quick outs, then surrendered three walks and a single, threw a wild pitch and finally saw Baines come to the plate to face him for the first time since the accident. A's catcher Mike Heath gave McLaughlin the sign for a sinker, away, and grinned. McLaughlin backed off and started laughing. "I threw a fastball," he says. "I wasn't interested in getting hit again." Baines popped out to end the inning.

Baines put the accident behind him. He played 20 more years and was one of the best players of his era. He never came close to hitting anyone again. "It's unfortunate," Baines, now a White Sox coach, says of the accident, "but it's part of the game."

McLaughlin played the 1982 season with Oakland. He worked 48 1/3 innings and had a 4.84 ERA. He bounced around the Triple A Pacific Coast League for three more seasons, mostly treating it, he says, "like a beer league." He never had another major league win. He married, had three children, started a real estate business and a baseball camp. In '92 Cubs manager Jim Lefebvre asked him to throw batting practice, and after seven years away it felt O.K. to be on a mound again. McLaughlin coached in the Cubs' minor league system, moved on to Montreal's, then worked as Baltimore's minor league pitching coordinator for three years, from 1999 through 2001. When Baines played for the Orioles in '98 and '99, he and McLaughlin talked a bit, no hard feelings. They played golf. In 2003 McLaughlin joined the Rockies as a pitching coach for the Double A Tulsa Drillers.

There aren't many days that McLaughlin isn't reminded of the accident. When he's home in Phoenix and the temperature hits 113° or so, the metal in his face gets so hot that the whites of his eyes turn red. He's considered a fine coach, committed and communicative, yet he hardly exudes a contagious passion. "I'm not a fan of baseball," he says softly. "Never was."

When the use of plastic batting helmets was mandated at all levels of professional baseball in 1971, serious injuries from pitched balls instantly declined. (Earflaps became mandatory for new players in 1983.) But the case of Astros shortstop Dickie Thon, whose brilliant career was derailed in 1984 by a fastball to his left eye from the Mets' Mike Torrez, was a shocking reminder of the harm that a pitched ball could still do. And the danger of a batted ball, especially to the man standing on the mound, never faded.

In 1987 Mariners pitcher Steve Shields, who a decade earlier had suffered a seizure and memory loss after taking a line drive to the face in Class A ball, had his cheek broken by a rip up the middle from the Twins' Kirby Puckett. In '95 Phillies reliever Norm Charlton fielded a comebacker from the Padres' Steve Finley with his face. A year later pitcher Mark Gubicza had his final season with the Royals cut short when his left leg was broken by a line drive hit by the Twins' Paul Molitor. In April '97 Mariners pitcher Josias Manzanillo, not wearing a protective cup, suffered tears in both testicles when the Indians' Manny Ramirez blasted a shot into his groin. The next month Tigers pitcher Willie Blair had his jaw broken when another Indian, Julio Franco, cracked a liner up the middle at 107 mph. Herb Score, then an Indians broadcaster, sat silently in the booth as that nightmare played out. It had been almost 40 years since his own accident. "You never see the ball," Score finally said into the mike. "You have no chance."

Just last Thursday, Giants reliever Joe Martinez took a line drive to the head from Brewers outfielder Mike Cameron and left the field with a bleeding forehead and a swollen right eye. As of Monday he was still in the hospital with a concussion and three hairline fractures in his skull but was expected to make a full recovery.

Surprisingly, no professional player at any level on the U.S. mainland has been killed by a batted ball. Of the 76 deaths caused in that manner -- five of which involved batters killed by their own foul tips -- all occurred in amateur games and included kids as young as six. In Puerto Rico, meanwhile, a catcher named Raul Cabrera died after he was struck in the throat by a foul tip during an amateur game in the town of Yauco in the early 1970s. Tino Sanchez, father of Rockies minor leaguer Tino Sanchez Jr., was sitting in the stands close to home plate in Ovidio (Millino) Rodriguez Park that day. "He was moving, trying to breathe," Sanchez says of Cabrera. "I thought he was going to be O.K., but the next day they told me the player had passed away. That was the first time that had happened in Puerto Rico."

Of course, coaches, umpires and other on-field personnel also run a risk of injury from batted balls. In 1964, 13-year-old Jerry Highfill died after being hit in the head while retrieving batting-practice balls for the Northwest League's Wenatchee (Wash.) Chiefs. Five years later major league umpire Cal Drummond was hit square on the mask by a foul tip at an Orioles game, injuring his brain, and died a year later from a stroke caused by decreased blood supply to the affected area.

Any career baseball man has a near-miss tale. In April 2002 Jackie Moore, then the manager of the Double A Round Rock (Texas) Express, missed nine games after being laid out by a batting-practice line drive. Moore suffered a broken cheekbone and a concussion and required surgery to repair a detached retina. Three years earlier, then Yankees bench coach Don Zimmer, who as a minor leaguer in 1953 had lain unconscious for 13 days after being beaned, survived a foul ball to the side of his face during a playoff game. The next day he wore an Army helmet.

When questioned on the topic, however, players and coaches say, almost to a man, that they're most concerned about the safety of the fans. Fifty-two spectators are known to have been killed by foul balls since 1887, two in pro games. In 1960 Dominic LaSala, 68, died after he was hit by a foul ball at a minor league game in Miami. Ten years later 14-year-old Alan Fish died five days after getting struck by a Manny Mota foul ball while sitting along the first base line at Dodger Stadium -- the only fatality caused by a batted ball in major league history.

"The first time I took my kids to Yankee Stadium, I was a nervous wreck," says Warren Stephens, whose late father, Jack, the billionaire financier and chairman of Augusta National Golf Club, was knocked out by a line drive while playing third base at Columbia (Tenn.) Military Academy in 1941. "We're just past third base but down really low, and I wouldn't take my eyes off of any pitch. I was scared we would get hammered."

But in the last few decades the sport has done little to shield its oft-distracted spectators. Unlike Japanese ballparks, which have protective screens running from behind the plate all the way to the outfield walls, U.S. major and minor league parks don't even have screens that extend as far as the dugouts -- thus allowing dozens of foul balls to fly into crowds at every game. There are, increasingly, ballparks like Tampa's George M. Steinbrenner Field, which has signs at lower-level entrances reading, CAUTION: WATCH FOR LIVE BATS AND BALLS LEAVING THE FIELD AT ALL TIMES. But with no standard, pro baseball leaves the decision on such signage, as well as the breadth of netting in each park, to the discretion of each team.

"It's about balancing the need to protect the fans with maintaining the baseball atmosphere we traditionally enjoy," says Dan Halem, senior vice president and general counsel of labor for Major League Baseball and a member of the game's Safety and Health Advisory Committee. "Netting in the ball fields would certainly change the experience of the game." What fan, after all, doesn't like to take home a foul ball? "Fans demand seats with no netting in front," Halem says. "That's the reality."

But if professional baseball is protected from legal action because of the 145-word warning on the back of each ticket that shifts all responsibility for injury to the fan, it doesn't lessen the danger. "Somebody's going to get hurt," says Hamilton, the pitcher who beaned Conigliaro. "Somebody's going to get hit with one of those broken bats, too, before long." Indeed, since baseball's Safety and Health Advisory Committee was reconstituted in 2008, all of its time -- and some $500,000 -- has been spent studying the increasing trend of bats splintering into dangerous flying shards. "The foul-ball issue has not been discussed," Halem says.

Veteran ballplayers, though, think about it constantly, and many insist that their loved ones sit behind protective netting. First baseman Alan Zinter, who retired in 2007 after playing nearly all of his 19-year career in the minor leagues, took it a step further; he urged complete strangers to sit behind the screen. "I've seen people get hit in the face, just crushed, blood everywhere," Zinter says. "The worst thing I saw was in Nashville: I was hitting left-handed and I check-swinged and hit a line shot over the dugout that hit a six-year-old boy right in the temple. It was slow motion for me; I'm looking right down the barrel and thinking, Oh, God, and it's heading right toward this family, and the father's not even watching. The kid was looking into leftfield, so he's not watching, and whack! Right in the head. They carried him out of the stadium.

"I couldn't even concentrate after that. I struck out. I kept calling after the game. Kid was in the hospital, and they said he's going to be O.K. Had a concussion, stayed that night. I said, 'Give me his number,' and I ended up calling him when I made it to the big leagues [later that season]." Zinter pauses, watching the moment unreel again in his mind. "His dad ran him up the steps..."

On March 4, 2007, Mike Coolbaugh and his close friend Jay Maldonado walked onto the field at Theodore Roosevelt High in San Antonio. They'd both been baseball stars there in the late 1980s, but this was no exercise in nostalgia. After 17 years in the minor leagues, Coolbaugh's playing options had seemingly dried up, but an offer had suddenly come from a professional team in Tabasco, Mexico: $10,000 just to show up and try out. Coolbaugh needed to get ready, and Maldonado had come to help; he could still roll out of bed and throw 88 mph.

Coolbaugh was one of those players who feared that his wife or children would get hit by a baseball ripped into the stands. "He was more worried about it than anybody I've ever met," says his wife, Mandy. "He was so aware of what a foul ball could do."

Maldonado and Coolbaugh set up the protective L screen in the grass in front of the pitcher's mound. Maldonado began to throw -- slurves, changeups and fastballs, mixing location in and out. His dad, Jesse, who had come along to watch, stood behind home plate, fingers curling through the backstop fencing. The right-handed Maldonado fired one 87-mph fastball and got a bit lazy, stopping on his follow-through so that his head didn't dip behind the high part of the screen. Coolbaugh swung. The ball blazed just over the inside corner of the L. Maldonado saw a flash of white in time to turn his head, and he felt a crack behind his right ear. He dropped to the ground like a sack of stones.

At first Jesse thought his son was gone. Finally Jay sat up, fighting to stay conscious by fixing his eyes on the fence, the bat, Coolbaugh's stricken face -- anything. He and Coolbaugh then sat on a bench, their breathing slowly returning to normal.

The wound left a sizable bruise, but Maldonado refused to see a doctor. Coolbaugh went home that night worried. He always paced when something upset him, and he kept it up that night after telling Mandy what happened, fighting back tears. "That can kill a guy," he said.

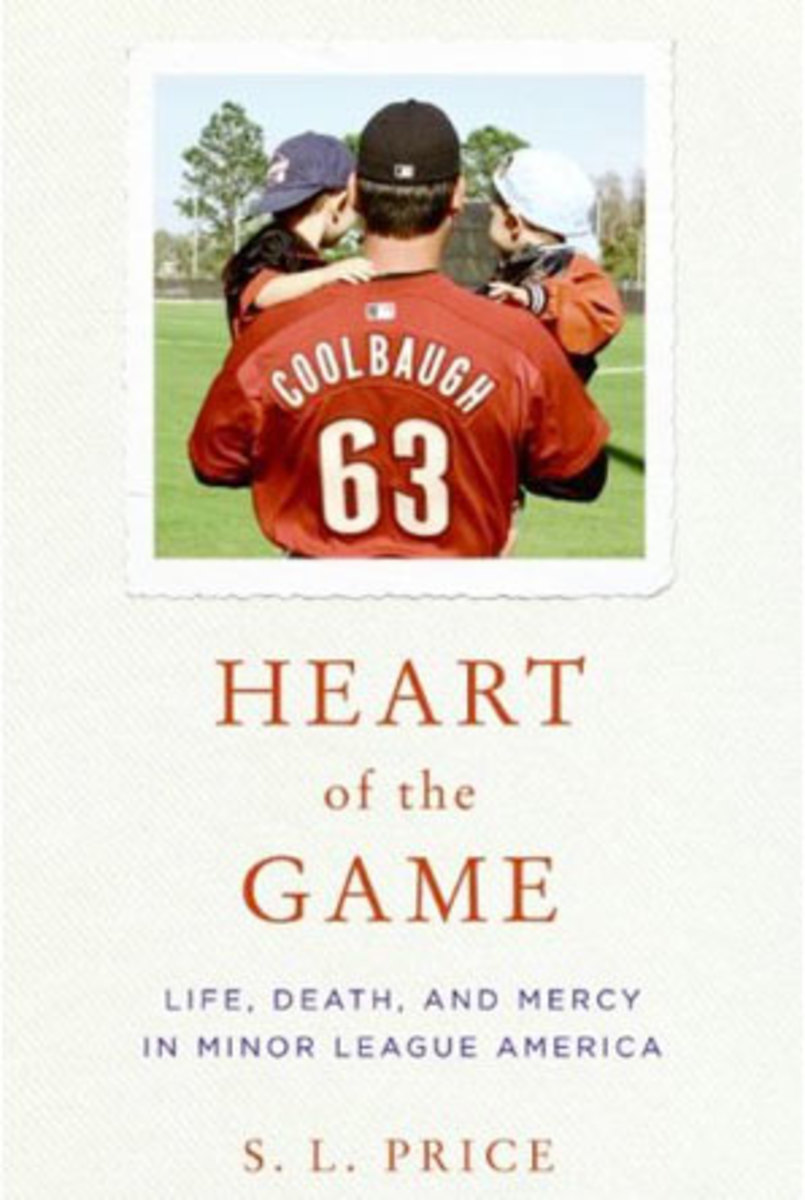

The Mexico tryout didn't lead to a job, but later that season Coolbaugh landed with the Tulsa Drillers as a first base coach. On July 22, 2007, after only 21/2 weeks in that position, Coolbaugh was struck in the back of the neck by a foul ball during a game at Dickey-Stephens Park in North Little Rock, Ark., and died almost instantly. He was 35.

In the park that night were several people who had experienced the harm a thrown or batted ball can do. Bo McLaughlin watched from the top step of the Drillers' dugout. Bill Valentine watched from the park's broadcast booth. Warren Stephens watched from his luxury box behind home plate. Tulsa pitcher Jon Asahina, whose skull had been fractured by a batted ball on the same field three months earlier, watched from the dugout. And 28-year-old Tino Sanchez, whose father had seen a ball kill a man years before, who himself had hit Rockies manager Clint Hurdle in the face with a ball during spring training in 2003, cracked the line drive that left Coolbaugh dead of a crushed left vertebral artery.

Six weeks after Coolbaugh's death, the 11-year career of Cardinals outfielder Juan Encarnacion ended when a foul ball hit by teammate Aaron Miles crushed his left eye socket as he stood in the on-deck circle at Busch Stadium. That November major league general managers approved rules that require base coaches at all levels of pro ball to wear helmets on the field and to stay within the coach's box until a struck ball has passed. According to MLB's Dan Halem, standardizing or expanding the use of protective netting in ballparks was not considered.