Glory days of The Boston Globe: the greatest sports staff ever

Call it off. Call the seventh game off. Let the World Series stand this way, three games for the Cincinnati Reds and three for the Boston Red Sox ...-- Ray Fitzgerald after Game 6 of the 1975 World Series

BOSTON -- It was October 21, 1975, and Lesley Visser, then a recent Boston College graduate, sat in the second row of a smoke-filled Fenway Park press box. Game 6 of the World Series between the Hub's Red Sox and Cincinnati's Big Red Machine unfurled on the field beneath, but she fixed her eyes on Ray Fitzgerald, the middle-aged man with the boxer's nose and poet's touch, one seat in front of her. Four days a week Visser read his lyric verses in the sports pages of The Boston Globe. On this night, she peered over his left shoulder to glimpse at an early edition.

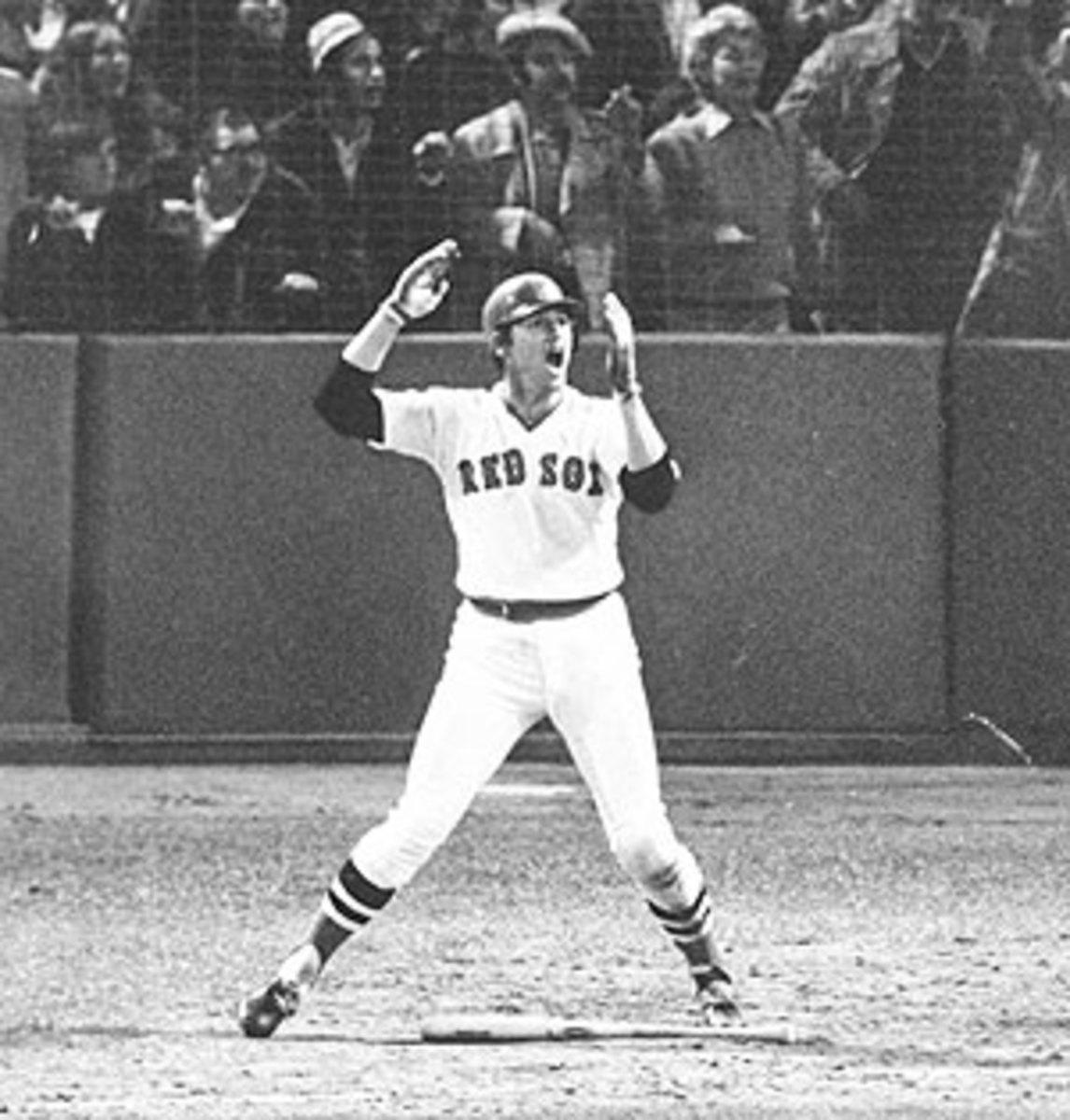

By the time Bernie Carbo came to bat as a pinch-hitter in the bottom of the eighth with two out and two men on, the Sox, trailing 6-3 in the game and 3-2 in the series, faced elimination. The seemingly unhittable Luis (El Tiante) Tiant had been touched for six runs, and had left the game, too late, in the inning's top half. Fitzgerald, a former minor league pitcher, was resigned to eulogizing another season. He began to type: You could feel it slipping away.

History tapped him on the shoulder before he could get any deeper. One of 35,205 bedside mourners, he watched the crowd jump to life as Carbo rocketed a 2-2 fastball into the centerfield seats, tying the game. Ripping the sheet from his typewriter, Fitzgerald let it fall to the floor. Like a groupie filching a lead singer's playlist, Visser snatched the discarded lede. "Ray was a god to me," she says.

Sox fans never read her deity's doubts the next day. After Carlton Fisk hit the game-winning homer in the 12th, Fitzgerald changed tone:

How can there be a topper for what went on last night and early this morning in a ballyard gone mad, madder and maddest while watching well, the most exciting game of baseball I've ever seen.

The next morning's headline read: "THE GREATEST GAME EVER!" Fitz-philes like novelist John Updike found his work infectious. As an entertainer, Fitzgerald played to New England's parochial pockets with humor and an uneven smile. A black-and-white photo of him ran atop his column on the section's front page. The inside pages brought forth the Globe sports staff's full body of work in all its splendor. What they produced each day was nothing less than a revolution of how newspapers covered sports.

From the mid-1970s to the early '80s, the Globe contained arguably the greatest collection of reporting talent ever assembled in a sports section, one that was unrivaled in its time and is sure never to be duplicated in an industry that today is bleeding talent. In those halcyon days, the staff's charge from hard-driving editor Dave Smith was: If a story warranted front-page space, cover it live. Reporter Will McDonough's directive back to Smith was elemental enough to be a Twitter post: "Get us space, money and get out of the way."

Space? They were afforded reams. Money? Smith rarely heard the term "budget" used at the family-owned paper. Editorial guidance? Only this: Reinvent the form. Take risks.

In a Red Sox-crazy town, Smith managed a lineup that was sportswriting's equivalent of the 1927 Yankees. Filing from Fenway was Peter Gammons, a fast-typing twenty-something who shagged flies in the outfield with the team most afternoons and scooped opposing writers in the clubhouse at night. Covering the Celtics courtside at the old Boston Garden above North Station was Bob Ryan, forever talking 75 mph in a 50 mph zone. High above the Hub's happenings was mustachioed columnist Leigh Montville, who, as Gammons says, "saw the world from a hot-air balloon." Blowing in and out of town was the correspondent Bud Collins, who commented on all sports but who was (and is) renowned as the greatest tennis writer extant. Joining Gammons at the Fens was Larry Whiteside, a pioneer by being the only African-American on the beat. Each of these writers contributed coverage for the '75 Series. Six of the Globe's 10 bylined reporters would go on to be honored by various Halls of Fame, with one (John Powers) winning a Pulitzer Prize.

"We had DiMaggio, Gehrig and Ruth," says Smith.

They went national with their endless travel but remained true to the locals. Blue-collar diehards could belly up to a Southie bar and drink in the details. Townies talking hockey scanned the wordage of Francis Rosa. Driving the high school beat were "Neil's Wheels": the trio of Visser, Dan Shaughnessy and Kevin Paul Dupont, working for schools editor Neil Singelais.

"To be in those pages was a dream," says Jim Craig, speaking of his high-school days in Easton, Mass. Craig, of course, later would receive even more play as a star at Boston University and then would crash the paper's front page as the goalie for the 1980 gold-medal-winning U.S, Olympic "Miracle on Ice" hockey team.

The pieces all came together in 1975. As politicians tip-toed around Boston's tinderbox of busing-related racial issues, the Globe prepared for an unprecedented run. The sports department, at the time publishing both morning and evening editions, printed two sections; one for all-non-baseball matters, and one solely for Series coverage. Today, Fitzgerald's Game 6 article hangs framed on a wall in Fenway's press box alongside Gammons' game story, which began: And all of a sudden the ball was there, like the Mystic River Bridge suspended out in the black of the morning.

Shaughnessy, now the lead columnist, can still recite Gammons' intro and keeps the hot-type cube that was used to print Fitzgerald's headshot in his desk at home as a talisman. That lost lede has survived, too. Visser, who left the paper in 1982 for TV, preserves the sheet at her home in Boca Raton, Fla. "We all wanted to write like that," she says. "You never knew what Ray would pull out of his hat."

*****

Want to know the real reason the Patriots' battle with Chuck Fairbanks ended in such haste? The inside story is ... -- Will McDonough, 1980

The linebackers coach, then in his second season as a NFL assistant, needed a seat on the team's flight. The 20-year veteran football reporter, who traveled with the squad, had an opening next to him. It was the fall of 1980 and the ultimate insider would be able to add Bill Parcells' name to his ever-widening network. "Will McDonough was a straight-talking Irishman and that's the kind of guy I liked," says Parcells, who went on to co-author a book with McDonough years later. "I knew Willie in a unique coach-reporter way."

McDonough's access was unmatched. Colleagues would sit within listening distance of his steel desk and marvel at the names on his call list. Raiders owner Al Davis, a friend from McDonough's 10 years covering the AFL, phoned frequently. On another line NFL commissioner Pete Rozelle could be waiting. "Will had more sources than the CIA," says Boston University hockey coach Jack Parker. "You didn't dare cross him."

Though he was cozy with many, the former quarterback from South Boston's Old Colony Projects never muted his competitiveness. In 1979, New England Patriots cornerback Raymond Clayborn, fresh out of his post-game shower, grew upset with a group of reporters standing by wide receiver Harold Jackson's locker. Clayborn bristled as the crowd spilled over by him and McDonough bristled back. Clayborn poked McDonough in the chin, and McDonough pushed him into his locker and punched him until it was clear who the winner was. "I thought, 'Oh, my God, these players are filled with amphetamines and already hate us,'" says Montville, who stood nearby. If he was going to get involved, Montville knew who would do him the least harm. "Where," he asked himself, "is the field goal kicker?"

McDonough punched out stories even quicker than he whipped up on players. To piece together an article, the 1984 Pulitzer Prize finalist would take a rumor, run it through his Rolodex and reveal the inner workings of the day's dealings. His streetwise characteristics played well with his subjects. "The players were drawn to him," says Vince Doria, who became editor in 1978 when Smith left for The Washington Star.

That McDonough's published collections of information were referred to as "Notebooks" was ironic. The man was all but allergic to notepad paper, refusing to write things down. Exclusive information like his drove the section, though. In 1973, the Globe published a 22-page special section called "Sportstown USA", which celebrated the locals' success, but it also pointed to the city's obsessions -- namely, that -- there was no such thing as an offseason. In winter, readers wanted to know what was happening with the Sox. In summer they wanted Celtics news. Year-round, Gammons and Ryan grew their notebook-emptying articles into weekly must-read material. Pathbreaking at the time, theirs was a format that has become standard nationwide. The columns were written in quick-hitting fashion but extended the reach of the paper as fans from across the country wrote to the office seeking copies. "People never lost interest," Smith says.

McDonough wrote for all fan bases. When Harry Sinden, a former Stanley Cup-winning coach of the Boston Bruins who also coached Team Canada in its Summit Series with the USSR, wrote a book on the 1972 event, he collaborated with McDonough. During and after practices Sinden would tape record his thoughts, and McDonough would later sit down with him for interviews. They targeted the Christmas season as a release date, and delivered the finished product in plenty of time. When the sales totals came back they were told they had the all-time best-selling hardcover in Canadian history. Months later, though, they didn't seem to be getting all that much money. Sinden had a lawyer investigate and his report was stunning to both men. Doubleday had not shorted them. The co-authors actually owed $7,000. "I couldn't even talk to [Will] that day," Sinden says. "He was laughing so hard."

It was reporting with a straight face, though, that made McDonough a pioneer. Following in the footsteps of Collins -- the first sportswriter to appear regularly on national television when he went on CBS in 1968 -- McDonough appeared on NBC's football telecasts a decade later. Though Collins eventually left the staff for television, contributing tennis and travel columns, McDonough remained a newspaperman first. On Sundays he showed off his craggy visage and cabbie hat from the Foxboro sidelines or out-of-town stadiums. The added face time grew his name, as well as the Globe's.

When McDonough died of a heart attack at age 67 in 2003, his family worried about how they would accommodate all the readers who would want to pay homage in person. "We figured we could help," Sinden says. On the carpeted floor of the FleetCenter (now T.D. BankNorth Garden), which is owned by the Bruins, friends, family and readers flocked to pay their last respects to McDonough, lying in his coffin like a head of state. "I'm not sure you'll see that again," Parcells says.

*****

They approached the victory stand in various stages of sobriety to meet the Lord himself. A few of them were even as drunk as lords ...-- John Powers, 1980, on the U.S. Olympic hockey team receiving its the gold medals

The job started before dawn, just as his father returned from his 12-hour shift as a city cop. By route's end the lad's hands invariably were always ink-stained. John Powers, the oldest of six children, started as a newspaper delivery boy when he was 11, slinging a bag over his shoulder and marching six blocks. Sundays were always the weightiest because of extra copies of The New York Times that had to be pushed in a shopping cart. "I used to read the papers along the way," says Powers, who carried six different newspapers in his bag. "I absorbed the city that way."

Powers' route took him farther than most. For high school, he attended Boston Latin and gained acceptance to Harvard in 1965. Before moving on, he handed his newsboy duties off to his next younger brother, Billy. At first unbeknownst to John, there was a full scholarship at Harvard for newsboys, which he received. Four years later, he graduated cum laude, then served a stint in the Navy and worked a year in Harvard sports information office. All that worldly training led him back to his original industry. The hiring of Powers prompted Fitzgerald to quip: "We have all the minorities now: a woman, a black and a Harvard grad."

Like the majority of the staff at the time, Powers was a writer, not a talker. Stymied by a stutter, he felt uncomfortable asking questions of athletes. To compensate he cut a wide swath, researching pieces that showed depth and range, spending 19 days per month on the road. After earning Massachusetts writer of the year honors, the frequent flyer was part of a team that won a Pulitzer for international news reporting. "Pound-for-pound he was the best writer," Shaughnessy says.

The Globe sports section was filled with lively language and writers wanted in. Ernie Roberts, the bespectacled, gentlemanly editor used the region's smaller newspapers and college publications as breeding grounds. In 1973, whenDupont, thena student at Boston University, got the call to be a substitute on the night desk, he hopped in his father's Mustang and sped down the Mass Turnpike. When he arrived at the office, he saw his name, his home phone number and the words "Last Resort" written in grease pencil on a piece of pink copy paper. His pay: $58 a night. "I would have worked for free," he says.

Not all aspirants were hired to the staff. Mike Lupica, who wrote features and took dictation from Collins and others while a student at Boston College, wanted to be a columnist when he graduated. Smith thought he was too young, so Lupica left for the New York Post. "I wasn't even junior varsity," Lupica says of his status. "I was like the student manager."

Another future star who got away was Bryant Gumbel, who had worked at Black Sports, a small monthly magazine in New York, where he rose to be editor. During an interview arranged by managing editor Thomas Winship, Smith found him talented, but said he thought his abilities would best fit elsewhere. "He should thank me because if I had hired him he'd be schlepping for six figures instead of millions," Smith says.

Smith, who was not a writer as previous editors had been, made the section easier to read with a scoreboard page and by using larger photos. "Montville painted portraits with words," Smith says. "You don't mess with Van Gogh's strokes. You sell them."

Montville, also a newsboy from New Haven, Conn., wrote long-form pieces that made T riders miss their stops. The staples at his desk were a Coca-Cola, a cheeseburger and the haze of smoke billowing from his burning cigarettes. "I never thought I'd read another Fitz, and then came Leigh," says Jackie MacMullan, who was hired when Fitzgerald, at 55, died in 1982 from a brain tumor and who would go on to become one of the nation's top pro basketball writers, both at the Globe and SI.

When a new byline impressed Winship, he left a note for the writer, requesting that the staffer pay him a visit. He wasn't enamored of everything that drew his attention. Powers and others slipped phrases like "It was as if a right hand came out of the occult" into the paper. By the time 10 to 15 writers had qualified for the occult "secret society" Winship found out and banned the line thereafter.

But shenanigans took a back seat to sophistication. Smith encouraged writers to review games as if they were dramatic shows. Assistant editor Tom Mulvoy would make notes in Visser's text with Latin phrases; Gammons, a frequenter of coffee houses in Cambridge, would lead stories with italicized song lyrics from Jackson Browne, Bob Dylan or whichever group had his ear.

Winship, a Harvard man who admittedly knew little about sports, welcomed outside writers and put their work above the fold. In 1979, Updike tried his hand at daily journalism. On Opening Day, he covered the Sox game with Fitzgerald and returned to the newsroom that evening. Ushered past the paste pots, pneumatic tubes, AP wire room and given a desk to write at, Updike struggled before delivering "First Kiss," which ran on the paper's front page. The many-headed monster called the Fenway Faithful yesterday resumed its romance with twenty-five youngish men in red socks who last year broke its monstrous big heart. Just showing up on so dank an Opening Day was an act of faith.

When finished with his work, Updike asked to stay and see the process through. Exposed to the innards of newspaper production, he walked with Mulvoy to the presses. "There's nothing special here," Mulvoy said, "but feel free to inhale the dust with me." Together they retired to a cup of tea and some toast with Fitzgerald. That evening and into night, Updike was of their nocturnal world. The novelist had learned what it was to be a newspaperman.

*****

What do you say after you've seen the greatest game of professional basketball ever played? That there should have been two winners? That it would have been a bargain at $250 courtside?-- Bob Ryan, June 3, 1976, on the Celtics' triple-overtime win over the Phoenix Suns in the NBA Finals

First pitch on a Sunday night in April at Fenway is 90 minutes away, but there goes Gammons, notepad in hand, pen cocked and ready behind home plate as the Yankees take batting practice. "I still think about those days," says Gammons, who is in his 21st year at ESPN, as he points to the press box. "I miss the competition, the running down to the clubhouse and back up to write."

Gammons arrived as an intern in the summer of 1968 on the same day as Ryan. He was a rising senior at North Carolina; Ryan was a recent Boston College graduate. Their first assignment was to call around to cities with major league baseball teams to gauge how Major League Baseball had reacted to the assassination of RobertF. Kennedy. Ryan was given the American League; Gammons the National. "Ryan was pissed because my name was on top," Gammons says with a smile. Ryan, whose name appeared as "Robert" for the first and only time in his career, clarifies the reason: "The names were arranged alphabetically."

For someone who had realized that he wanted to be a sportswriter while arguing sports in a bar, Gammons could not have found a more able debate partner than Ryan. Both had attended elite prep schools (Gammons, Groton; Ryan, Lawrenceville) but were capable of rolling up their sleeves and throwing down, using encyclopedic and arcane knowledge as haymakers. Verbal jousts were a part of the eccentric Globe sports culture, along with writers who wore slippers and expensed velvet clothes hangers. One day, Tom Fitzgerald, who covered the Bruins, was writing a story when Ryan and Gammons erupted into a spirited back-and forth. "Is my typing bothering you two gentlemen?" Fitzgerald asked.

Clif Keane, an old-time, acerbic baseball scribe, once described what it would be like to assign them to the same game. "Ryan would write about umpires," said Keane, "Gammons would write about wars and symphonies, and you'd need a third f----- guy for game talk."

Ryan's passion was primordial. The son of an athletics promoter who grew up mimicking Princeton star Bill Bradley's jump shot in Trenton, N.J., he did not consider a game complete until he read about it in the next morning's paper. While at Boston College, he did play-by-play for the campus radio station, worked extra shifts in the cafeteria to follow the team to New Orleans one Christmas break and grew to be a minor league baseball junkie. To this day he keeps score at every baseball game he attends. "He's never lost that 12-year-old's enthusiasm," says Celtics legend Bob Cousy, who co-authored a book with Ryan.

Their fervor was revealed in their work habits. Gammons -- who hailed from Groton, Mass., the same small hometown as Shaughnessy -- would arrive at Fenway by noon most days and not leave until after midnight. At 23, Ryan caught on with the Celtics beat, and played catch-up until he became an authority -- perhaps the authority -- himself. Young and enthusiastic, they traveled with the teams and Gammons held a locker in the Sox clubhouse. "Jim Rice would underline a phrase," Gammons recalls, "hand it to me and say, 'Let me know if you took a shot at me.'"

While Gammons left the Globe first for a 16-month stint at Sports Illustrated and then permanently for ESPN in the late '80s, he still receives mail at the Globe and had a crateful until recent years. Over more than four decades, Ryan has remained stationed on Morrissey Blvd. for all but 19 months. Upset that he had been passed over for the columnist position sadly made available by Fitzgerald's 1982 death, Ryan was approached by Channel 5 reporter Clark Booth about shifting roles at Fitzgerald's funeral. Ryan jumped in front of the camera. "He hit me at the right time," said Ryan, who continued to write a weekly column during most of his hiatus and returned after a Thanksgiving eve talk with Winship.

Despite their divergent paths, they've reached unequalled heights. "They weren't just columnists," says retired political columnist Martin F. Nolan. "They were commissioners."

Ryan's cubicle is a reliquary. A photo of Jack Barry, the paper's original Celtics beat writer who all but adopted Ryan when he joined the staff, hangs on one wall. Pictures of Brooklyn's Ebbets Field and Boston's Braves Field appear as well. Attached to a beam nearby is a sign that reads: "Accuracy is the cornerstone of our business". Behind Ryan sits a typewriter. "We keep it as a memento," he says.

In early May, at the National Sportscasters and Sportswriters Hall of Fame in Salisbury, N.C., Ryan received the Sportswriter of the Year honors on the same night that Montville, who left the Globe to write at SI and author four books, was inducted, joining Collins and McDonough on the 40-man writer roster. While at the podium to introduce Montville, Doria, now ESPN's director of news, said the biggest mistake he made as sports editor was not promoting Ryan in 1982. Curious whether Doria ever had made that admission to Ryan, Montville asked his longtime colleague. "No," Ryan said, "he had not."

They all fear the day is coming when there will be no front page of the sports section to commemorate a championship won, no all-scholastic contribution to schoolboy lore and no tout telling you there's more coverage inside. In recent years buyouts have gutted the staff and budget cuts have restricted its travel. The New York Times Co., which bought the paper for $1.1 billion as its "crown jewel" in 1993, threatened to close its doors last month, but later reached an agreement with the paper's unions that spared it for now.

After all the five-hour Yankee/Sox games and the triple-overtime NBA Finals contests, there has always been morning in New England. Talking to Powers about buyouts, Ryan, now 63, said he wasn't interested. Powers, who along with Shaughnessy and Dupont are the only other staffers still left from that '70s golden age, offered that even without the paper, surely Ryan would be comfortable given his television work opportunities. Ryan disagreed. He explained that when he appears on Pardon the Interruption or The Sports Reporters, the most important part of his introduction isn't "Bob Ryan." It is "of The Boston Globe."