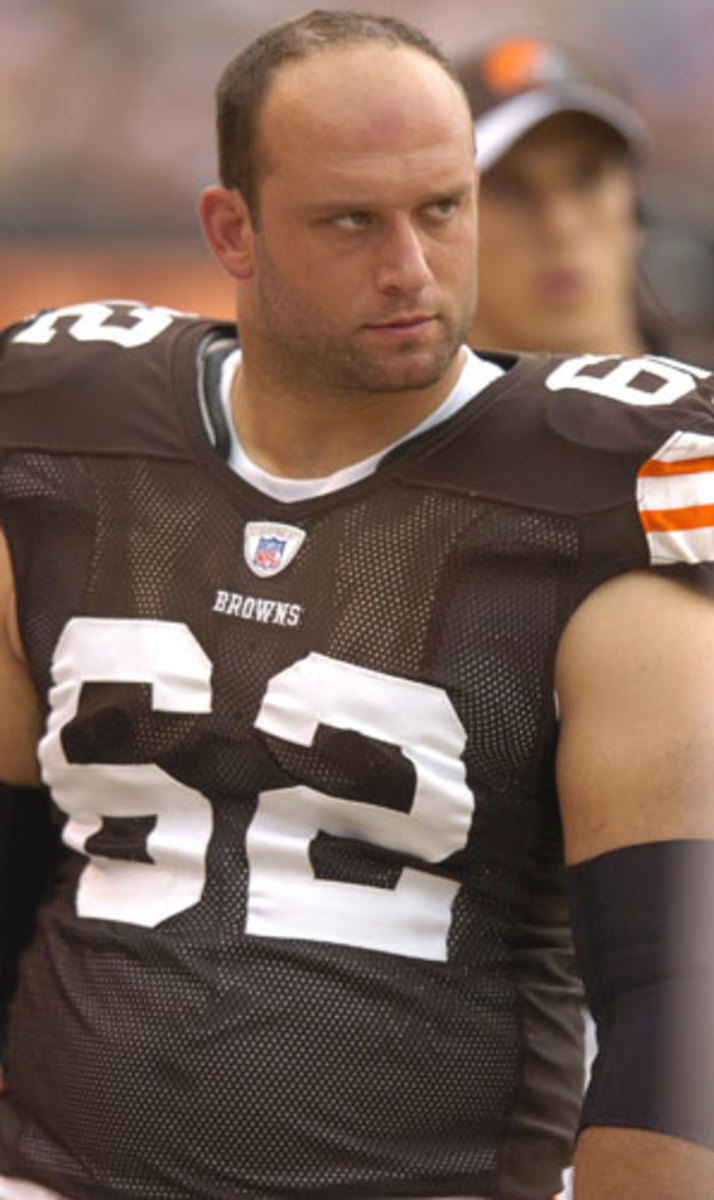

Lennie Friedman goes from professional athlete to regular Joe

Cleveland Browns training camp opened on Aug. 1 and Lennie Friedman didn't care.

There were no heart palpitations. No sweaty palms. No feelings of remorse and no second thoughts and no yearning for a final moment in the Berea, Ohio, sun. As old offensive line chums like Hank Fraley and Ryan Tucker and Joe Thomas slammed into one another as if they were performing some sort of water buffalo mating ritual, Friedman thought to himself ... well, nothing. Not. One. Tiny. Thing.

"Forgot it was taking place," he says. "Honest to goodness."

The oversight is understandable. Friedman, a 32-year-old New Jersey native who recently announced his retirement after a four-team, eight-year NFL career, is now a first-year MBA student at Duke, pursuing his goal of one day becoming an entrepreneur. Though football occ asionally pops into his head, it lingers for as long as a Shannon Hoon solo -- usually tailed off by the thought, "Thank God I'm done."

His odds of returning to the league? "I'd place it at negative 1,000," he says. "Maybe more."

Friedman is anything but bitter. Thanks to the NFL, the former second-round pick out of Duke is financially secure and emotionally content. He lived a dream, and reflects glowingly at past battles with men like Joey Porter and Shawne Merriman. Yet there is also this thing called ... life. For eight years, Lennie Friedman did exactly as he was told. He arrived at this time. Ate this meal. Did this drill and that drill, then lifted this weight this many times before spending this many minutes in a bucket of ice water. Such is the oft-banal existence of the paid athlete, where active brain waves are optional and existence's irksome realities -- doctor appointments, dinner reservations, rental cars -- are neatly handled by others. To work as an American professional athlete is to simultaneously be the king of the world and the most sheltered being on the planet. "You're in a bubble," Friedman says. "No doubt about it."

Now, he feels liberated. Friedman has lost a whopping 70 pounds, eating one or two slices of pizza instead of, oh, eight and no longer merely stuffing (Oreos!), stuffing (ziti!), stuffing (ice cream!) his mouth for the sake of weight maintenance. "I'm able to jog and run and do all sorts of things without soreness," he says. "It's weird, seeing myself in the mirror after all those years of being so big. But I like it. I really like it."

As you read this column, hundreds upon hundreds of anti-Lennie Friedmans are doing everything to hang on. They are engulfing supplements and calling in favors; they are begging promoters for one last fight and convincing general managers that the ol' right arm had a couple of more heaters. Despite 8,000 reasons to do so, Brett Favre can't leave. Neither can Shane Mosley. Or Malik Rose. Or John Smoltz. Or Chris Chelios. Heck, Jason Giambi -- he of 407 career home runs -- just signed to play Triple-A ball in Colorado Springs.

Though happy to be done, Friedman gets it. "Everyone envies your job when you're an athlete," he says. "You're a part of big games and big victories. You run out onto a field and 60,000 people are screaming. I get it, because I've been there.

"But I thought about the decision for a long time," he says. "I have three kids, and I want to be able to play with them. I didn't want my knees and my neck to be destroyed. I was given the chance to play football for a long time, and it was wonderful."

He pauses.

"But it was time to start a new life."