Hodge still a staple in Oklahoma

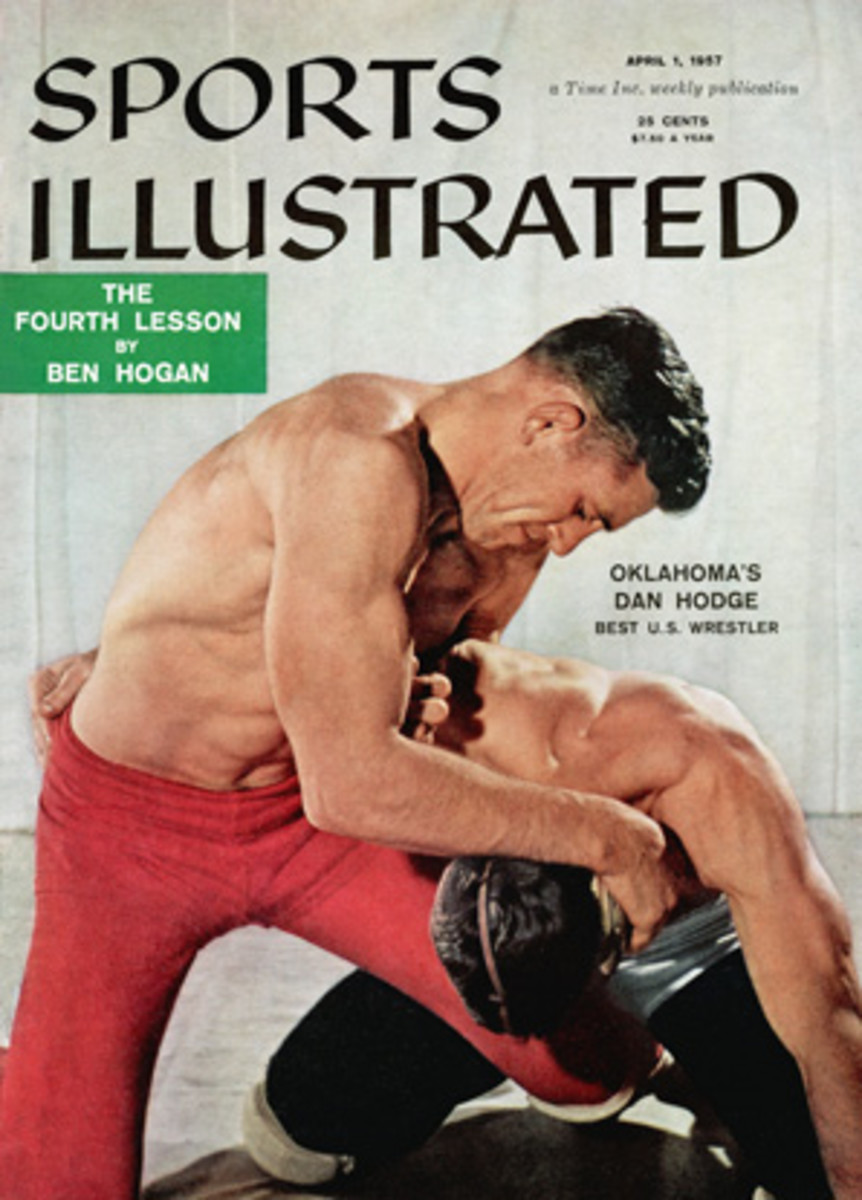

With the gravitas of a man experienced at overcoming challenges and challengers, 77-year-old Dan Hodge says with certainty he would have been a great mixed martial artist. Ask anyone who claims Hodge as a friend to elaborate. They'll tell you the only amateur wrestler to grace the cover of SportsIllustrated knows what he's talking about.

He was just five decades too early.

In April 1957, during the run-up to Hodge's third national collegiate championship at 177 pounds for the University of Oklahoma, writer Don Parker followed the unassuming country boy from Perry, Okla., for a week.

Like many of Hodge's sporting memories, he culls details with expertise. This is the same if he describes circumstances of his first medal in junior high, or the silver at the 1956 Melbourne Olympics. Years of experience in perfecting a craft gave him a gritty, unfettered perspective. The details are vivid and the memories hardly faded, from the violent prizefighting inside a cigar-smoke-filled Madison Square Garden, to the day he first felt strength -- real, raw strength -- rip through his body. And the rare few times it repeated.

"Something jogs my memory and it just comes back," said Hodge

During his reign at Oklahoma, opponents found Hodge to be overwhelming. "He's too good for college boys," one coach said during the wrestler's run of 26 consecutive pins. Forty-six times he stepped on the mat. Forty-six times he won, including an astounding 36 matches by way of forcing shoulders to the mat. There wasn't a man who crossed paths with Hodge that so much as sniffed a standing takedown.

"You can't go anywhere in wrestling circles where people don't know Danny Hodge," said current Oklahoma wrestling coach, Jack Spates. "And even if they don't know the name, they know the stories."

Many don't know, after just six months of training, Hodge was the 1958 Golden Gloves national heavyweight champion, back when it meant something. Eventually he crossed over to pro-wrestling, when it was much more wrestling than entertainment, and learned the application and defense of submissions.

He was, by all accounts, supremely gifted with attributes that made him a terror in one-on-one physical competition. Hodge's fighting instinct is as much a condition of his upbringing as it is a consequence of his DNA. He said he never fit in anywhere after his childhood home burnt to the ground. His mother was badly injured; She needed 52 blood transfusions and countless skin grafts. Without his dad around, Hodge said he "more or less grew up on my own."

"He would flat tell you, when he got on the mat, he was going to hurt you -- and he did," said Joe Miller, executive director for the Oklahoma State Athletic Commission, of which Hodge is chairman.

"I did handle you a little rough," Hodge said. "But that was for a purpose because you weren't lasting until the second period. That was a message I was sending to my opponents."

Hodge's famous grip -- strengthened by pulling double sheets of newspaper into a ball with his fingers, reversing then repeating all day and night Monday through Friday -- was severe enough to leave a scar on fellow Olympian Jim Peckham's arm decades after their last match.

A year and a half ago, during a reconfirmation hearing for his chairmanship, an apple and a pair of pliers were delivered to him on a silver platter. Both items are mainstays in the Hodge mythology. As he's done countless times, Hodge took the apple into one of his paws and juiced the thing without any kind of trouble. Then he ripped the pliers in two.

"This is what Mr. Hodge is capable of," joked the state senator who sponsored him. "We recommend that you confirm him."

While Hodge may not have had the opportunity to fight as a professional mixed martial artist, he played an important part in the legalization of MMA in Oklahoma by personally selling state legislators on the sport.

Hodge's experience in boxing led him to believe fighters needed as much protection as people would be willing to give. After the Golden Gloves, Hodge turned pro, winning eight of 10 fights. However, he never received a dime and felt burned.

"I said I can get all the fights I want in Perry, Okla., for nothing," he laughed. "And don't have to train as near as hard."

Hodge returned home and took out much of his aggression on "the Air Force boys who used to come over here. I said don't come back Saturday. I will take you out of town.

"I've had my share of fights here in Perry and haven't lost one."

Hodge decided pro wrestling was a better option than his previous career: supervising the viscosity of mud in gas wells.

At his peak Hodge earned upwards of $80,000 a year. He may have been away from Perry (the wrestling capital of the world, he claims) more than he wanted, but the allure of the crowd and an insatiable desire to prove he was the best fueled long road trips as much as the gasoline that kept his Volkswagen station wagon humming.

Twenty years after earning a silver in Melbourne, Hodge travelled highways throughout the southeast so regularly that he invested in a CB radio. Truckers working similar routes learned when "ringmaster" -- Hodge's appropriately chosen handle -- was on the line telling stories, an hour's drive could feel like 10 minutes.

On the night of March 15, 1976, though, time stood still.

Driving though Louisiana, Hodge fell asleep at the wheel. He careened off a bridge, plunging nine feet below the surface of an icy creek that quickly filled the space inside his car. The wrestler awoke to two terrifying sensations: the possibility of dying and the searing pain that accompanies a broken neck.

Hodge managed, barely, to squeeze through a mangled space where a windshield once protected him on those long rides. He pulled himself ashore, then up to the side of the road. A trucker before the crash notified anyone within earshot that Hodge's headlights had disappeared behind him. He was found and transported to a hospital.

Doctors were wrong about Hodge never walking again. Just nine months after surgery to remove a chunk of bone from his hip, he reclaimed the pro wrestling championship belt he had held multiple times over a decade.

"I wanted people to know I was the champion," he said.

Hodge's athletic career was over. He relinquished his crown and walked away from competition, and for a time, it left without purpose. But off the road and back in Perry with his wife Dolores, Hodge mustered the discipline to move forward with his life.

Today, much of the pain he accumulated over the years lingers, though it's offset considerably by the usefulness he feels working with the Oklahoma commission, a position he's held since 1997.

MMA in the Oklahoma has steadily increased its footprint beginning in 2001, moving from three events to an all-time high of 42 last year. Wednesday, a moment Miller believes will validate the sport in the state, marks the first fight card in the state under the UFC banner in 15 years.

Nearly three weeks prior to Sept. 16, when UFC Fight Night 19 is scheduled to go down at the Cox Convention Center, the card had already topped the all-time record for ticket sales for a combative sports event in Oklahoma, besting a Tommy Morrison card on HBO in 1993.

Hodge plans to attend the UFC event in his role of chairman, watching men fight in a sport he wishes he could have participated.

And Dan Hodge could have been a great fighter.

"Even today you may not want to test me," he said. "I'll let you choke me. Before you know it, your wrist is broke -- if I want. I take what you give me, but in the long run I make you give me what I want."

VAULT:Hodge is the man to beat (4.1.57)