'I Hate Tennis'

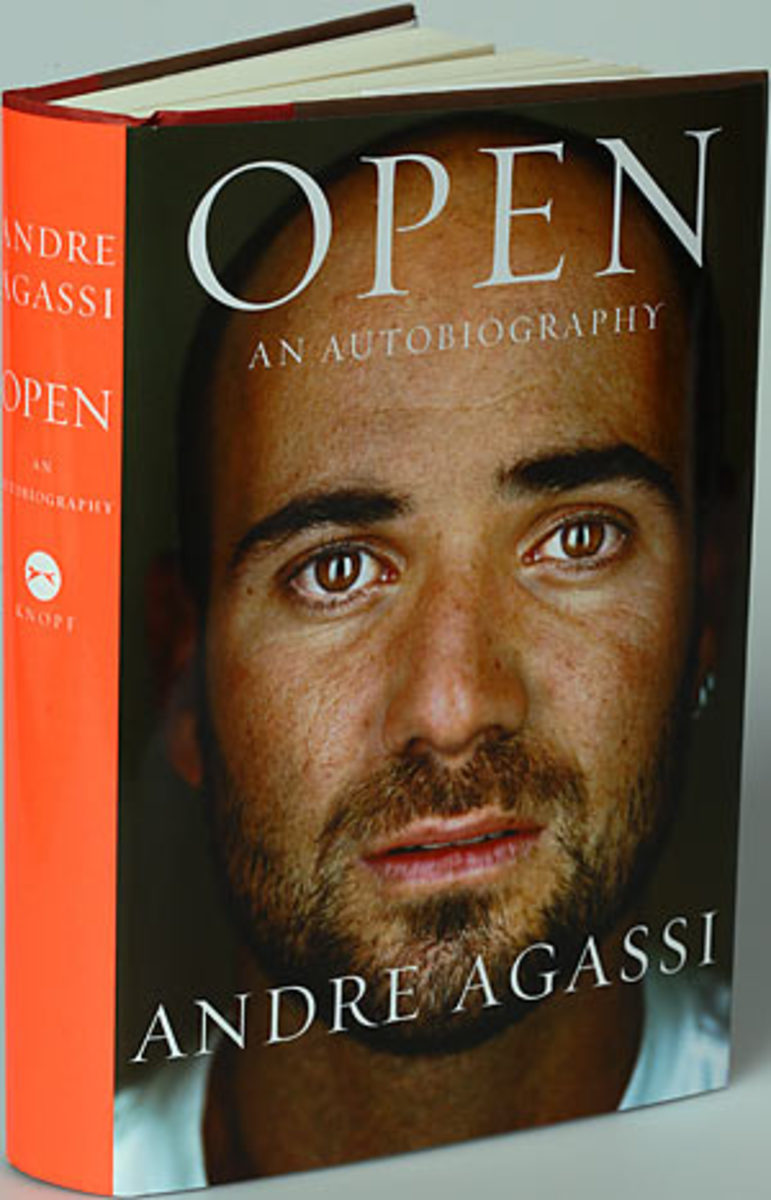

Excerpted from Open: An Autobiography, by Andre Agassi. © 2009 ALA Publishing LLC. Published by arrangement with Alfred A. Knopf, an imprint of The Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Random House Inc.

I open my eyes and don't know where I am or who I am. Not all that unusual -- I've spent half my life not knowing. Still, this feels different. This confusion is more frightening. More total.

I look up. I'm lying on the floor beside the bed. I remember now. I moved from the bed to the floor in the middle of the night. I do that most nights. Better for my back. Too many hours on a soft mattress causes agony.

I count to three, then start the long, difficult process of standing. With a groan, I roll onto my side, then curl into the fetal position, then flip over onto my stomach. Now I wait, and wait, for the blood to start pumping.

I'm a young man, relatively speaking. Thirty-six. But I wake as if 96. After two decades of sprinting, stopping on a dime, jumping high and landing hard, my body no longer feels like my body. Consequently my mind doesn't feel like my mind. I run quickly through the basic facts. My name is Andre Agassi. My wife's name is Stefanie Graf. We have two children, a son and a daughter, five and three. We live in Las Vegas but currently reside in a suite at the Four Seasons Hotel in New York City, because I'm playing in the 2006 U.S. Open. My last U.S. Open. In fact my last tournament ever. I play tennis for a living, even though I hate tennis, hate it with a dark and secret passion, and always have.

As this last piece of identity falls into place, I slide to my knees and wait. In a whisper I say: Please let this be over.

Then: I'm not ready for it to be over.

The fatigue of these final days has been severe. Apart from the physical strain, there is the exhausting torrent of emotions set loose by my pending retirement. Now, rising from the center of the fatigue comes the first wave of pain. I grab my back. It grabs me. I feel as if someone snuck in during the night and attached one of those antitheft steering-wheel locks to my spine. How can I play in the U.S. Open with the Club on my spine?

I was born with spondylolisthesis, meaning that a bottom vertebra parted from the other vertebrae, struck out on its own, rebelled. (It's the main reason for my pigeon-toed walk.) With this one vertebra out of sync, there's less room for the nerves inside the column of my spine, and with the slightest movement the nerves feel that much more crowded. Throw in two herniated disks and a bone that won't stop growing in a futile effort to protect the whole damaged area, and those nerves start to feel downright claustrophobic. When they send out distress signals, a pain runs up and down my leg that makes me suck in my breath and speak in tongues. At such moments the only relief is to lie down and wait. Sometimes, however, the moment arrives in the middle of a match. Then the only remedy is to alter my game -- swing differently, run differently, do everything differently. That's when my muscles spasm. Everyone avoids change; muscles can't abide it. Told to change, my muscles join the spinal rebellion, and soon my whole body is at war with itself.

Gil Reyes, my trainer, my friend, my surrogate father, explains it this way: Your body is saying it doesn't want to do this anymore.

My body has been saying that for a long time, I tell Gil. Since January, however, my body has been shouting it. My body doesn't want to retire -- my body has already retired. My body has moved to Florida and bought a condo and white Sansabelts. So I've been negotiating with my body, asking it to come out of retirement for a few hours here, a few hours there. Much of this negotiation revolves around a cortisone shot that temporarily dulls the pain. Before the shot works, however, it causes its own torments.

I got one yesterday, so I could play tonight. It was the third shot this year, the 13th of my career, and by far the most alarming. The doctor, not my regular doctor, told me brusquely to assume the position. I stretched out on his table, face-down, and his nurse yanked down my shorts. The doctor said he needed to get his seven-inch needle as close to the inflamed nerves as possible. But he couldn't enter directly, because my herniated disks and the bone spur were blocking the path. His attempts to circumvent them, to break the Club, sent me through the roof. First he inserted the needle. Then he positioned a big machine over my back to see how close the needle was to the nerves. In and out and around he maneuvered the needle, until my eyes filled with water.

Finally he hit the spot. Bull's-eye, he said.

In went the cortisone. The burning sensation made me bite my lip. Then came the pressure. I felt infused, embalmed. The tiny space in my spine where the nerves are housed began to feel vacuum packed. The pressure built until I thought my back would burst.

Pressure is how you know everything's working, the doctor said.

Words to live by, Doc.

I'm seven years old, talking to myself, because I'm scared, and because I'm the only person who listens to me. Under my breath I whisper: Just quit, Andre, just give up. Put down your racket and walk off this court, right now. Wouldn't that feel like heaven, Andre? To just quit? To never play tennis again?

But I can't. Not only would my father, Mike, chase me around the house with my racket, but something in my gut, some deep unseen muscle, won't let me. I hate tennis, hate it with all my heart, and still I keep playing, keep hitting all morning, and all afternoon, because I have no choice. No matter how much I want to stop, I don't. I keep begging myself to stop, and still I keep playing, and this gap, this contradiction between what I want to do and what I actually do, feels like the core of my life.

At the moment my hatred for tennis is focused on the dragon, a ball machine modified by my fire-belching father and set up on the court he built in our yard in Las Vegas. Midnight black, mounted on big rubber wheels, the dragon is a living, breathing creature straight out of my comic books. It has a brain, a will, a black heart -- and a horrifying voice. Sucking another ball into its belly, the dragon makes a series of sickening sounds. As pressure builds inside its throat, it groans. As the ball rises slowly to its mouth, it shrieks. And when the dragon takes dead aim at me and fires a ball 110 miles an hour, the sound it makes is a bloodthirsty roar. I flinch every time.

My father has deliberately made the dragon fearsome. He's given it an extra-long neck of aluminum tubing, and a narrow aluminum head, which recoils like a whip every time the dragon fires. He's also set the dragon on a base several feet high and moved it flush against the net, so the dragon towers above me. I'm small for my age, but when standing before the dragon, I look tiny. Feel tiny. Helpless.

My father wants the dragon to tower over me not simply to command my attention and respect. He wants balls that shoot from the dragon's mouth to land at my feet as if dropped from an airplane. The trajectory makes the balls nearly impossible to return in a conventional way: I need to hit every ball on the rise, or else it will bounce over my head. But even that's not enough for my father. Hit earlier, he yells. Hit earlier.

My father yells everything twice, sometimes three times, sometimes 10. Harder, he says, harder. But what's the use? No matter how hard I hit a ball, no matter how early, another ball comes back. Every ball I send across the net joins the thousands that already cover the court. Not hundreds. Thousands. They roll toward me in perpetual waves. I have no room to turn, to step, to pivot. I can't move without stepping on a ball -- yet I can't step on a ball, because my father won't bear it. Step on one of my father's tennis balls and he'll howl as if you stepped on his eyeball.

Every third ball fired by the dragon hits a ball already on the ground, causing a crazy sideways hop. I adjust at the last second, catch the ball early, and hit it smartly across the net. I know this is no ordinary reflex. I know there are few children in the world who could have seen that ball, let alone hit it. But I take no pride in my reflexes, and I get no credit. It's what I'm supposed to do. Every hit is expected, every miss a crisis.

My father says that if I hit 2,500 balls each day, I'll hit 17,500 balls each week, and at the end of one year I'll have hit nearly one million balls. He believes in math. Numbers, he says, don't lie. A child who hits one million balls each year will be unbeatable.

Hit earlier, my father yells. Damn it, Andre, hit earlier. Crowd the ball, crowd the ball.

Now he's crowding me. He's yelling in my ear. It's not enough to hit what the dragon fires at me; my father wants me to hit it harder and faster than the dragon. He wants me to beat the dragon. The thought makes me panicky. How can you beat something that never stops? Come to think of it, the dragon is a lot like my father. Except my father is worse. At least the dragon stands before me, where I can see it. My father stays behind me. I rarely see him, only hear him, day and night, yelling in my ear.

More topspin! Hit harder. Hit harder. Not in the net! Damn it, Andre! Never in the net!

Nothing sends my father into a rage like hitting a ball into the net. Over and over my father says: The net is your biggest enemy.

My father has raised the enemy six inches higher than regulation. If I can clear my father's high net, he figures, I'll have no trouble clearing the net one day at Wimbledon. Never mind that I don't want to play Wimbledon. What I want isn't relevant.

Hit harder, my father yells. Hit harder. Now backhands. Backhands. My arm feels like it's going to fall off. On one swing I surprise myself by how hard I hit, how cleanly. Though I hate tennis, I like the feeling of hitting a ball dead perfect. When I do something perfect, I enjoy a split second of sanity and calm.

Work your volleys, my father yells, or tries to. An Armenian born in Iran, my father speaks five languages, none of them well, and his English is heavily accented. He mixes his v's and w's, so it sounds like this: Vork your wolleys. Of all his instructions, this is his favorite. He yells it until I hear it in my dreams. Vork your wolleys, vork your wolleys.

I get an idea. Accidentally on purpose, I hit a ball high over the fence. I catch it on the wooden rim of the racket, so it sounds like a misfire. I do this when I need a break, and it crosses my mind that I must be pretty good if I can hit a ball wrong at will.

My father hears the ball hit wood and looks up. He sees the ball leave the court. He curses. But he heard the ball hit wood, so he knows it was an accident. He stomps out of the yard, to the desert. I now have 4 1/ 2 minutes to catch my breath and watch the hawks circling lazily overhead.

My father likes to shoot hawks with his rifle. Our house is blanketed with his victims, dead birds that cover the roof as thickly as tennis balls cover the court. My father says he doesn't like hawks because they swoop down on mice and other defenseless desert creatures. He can't stand the thought of something strong preying on something weak. (This also holds true when he goes fishing: Whatever he catches, he kisses its scaly head and throws it back.) Of course he has no qualms about preying on me, no trouble watching me gasp for air on his hook.

Violent by nature, my father is forever preparing for battle. He shadowboxes constantly. He keeps an ax handle in his car. He leaves the house with a handful of salt and pepper in each pocket, in case he's in a street fight and needs to blind someone. Of course some of his most vicious battles are with himself. He has chronic stiffness in his neck, and he's perpetually loosening the neck bones by angrily twisting and yanking his head. When this doesn't work he shakes himself like a dog, whipping his head from side to side until the neck gives and makes a sound like popcorn popping. When even this doesn't work, he resorts to the heavy punching bag that hangs from a harness outside our house. My father stands on a chair, removes the punching bag and places his neck in the harness. He then kicks away the chair and drops a foot through the air, his momentum abruptly halted by the harness. The first time I saw him do this, I had no doubt he'd killed himself. I ran to him, hysterical. Seeing the stricken look on my face, he barked: What the f--- is the matter with you?

Most of his battles, however, are against others, and they typically begin without warning, at the most unexpected times. In his sleep, for instance. He boxes in his dreams and frequently punches my dozing mother. In the car too. If another driver crosses him, if another driver cuts him off or objects to being cut off by my father, everything goes dark.

I'm riding with my father one day, and he gets into a shouting match with another driver. My father stops his car, steps out, orders the man out of his. Because my father is wielding his ax handle, the man refuses. My father whips the ax handle into the man's headlights and taillights, sending sprays of glass everywhere.

Another time my father reaches across me and points his handgun at another driver. He holds the gun level with my nose. I stare straight ahead. I don't move. I don't know what the other driver has done wrong, only that it's the automotive equivalent of hitting into the net. I feel my father's finger tensing on the trigger. Then I hear the other driver speed away, followed by a sound I rarely hear -- my father laughing. He's busting a gut.

Such moments come to mind whenever I think about telling my father that I don't want to play tennis. Besides loving my father and wanting to please him, I don't want to upset him. I don't dare. Bad stuff happens when my father is upset. If he says I'm going to play tennis, if he says I'm going to be No. 1 in the world, that it's my destiny, all I can do is nod and obey.

Besides the occasional exhibition with a top-ranked player, my public matches are mostly hustle jobs. I have a slick routine to lure in the suckers. First, I pick a highly visible court, where I play by myself, knocking the ball all over the place. Second, when some cocky teenager or drunken casino guest strolls by, I invite him to play. Third, I let him beat me, soundly. Finally, in my most pitiful voice I ask if he'd like to play for a dollar. Maybe five? Before he knows what's happening, I'm serving for the match and 20 bucks.

I don't tell my father about my side business. Not that he'd think it was wrong. I just don't feel like talking to my father about tennis any more than is absolutely necessary. Then my father stumbles into his own hustle. It happens at Cambridge Racket Club in Vegas. As we walk in one day, my father points to a man talking with Mr. Fong, the owner.

That's Jim Brown, my father whispers. Greatest football player of all time.

He's an enormous block of muscle wearing tennis whites and tube socks. He's complaining to Mr. Fong about a money match that fell through. My father steps forward.

You looking for a game?

Yeah, Mr. Brown says.

My son Andre will play you.

Mr. Brown turns. He looks at me, then back at my father.

I ain't playing no eight-year-old boy!

Nine.

Look, Mr. Brown says, I don't play for fun, O.K.? I play for money.

My son will play you for money.

I feel a bead of sweat start down my armpit.

Yeah? How much?

My father laughs and says, I'll bet you my f------ house.

I don't need your house, Mr. Brown says. I got a house. Let's say ten grand.

Done, my father says.

I walk toward the court.

Slow down, Mr. Brown says. I need to see some money up front.

I'll go home and get it, my father says. I'll be right back.

My father hurries out the door. I feel a heaviness in the center of my chest. What happens to me, to my father, to my mother and my three siblings, if I lose my father's life savings?

I've played under this kind of pressure before, when my father, without warning, has chosen an opponent and ordered me to beat him. But it's always been another kid, and there's never been money involved. This thing with Mr. Brown is different, and not just because my family's life savings are riding on the outcome. Mr. Brown disrespected my father, and my father can't punch him out. He needs me to do it. So this match will be about more than money. It will be about respect and manhood and honor -- against the greatest football player of all time.

Slowly I become aware that Mr. Brown is watching me. Staring. He walks over and shakes my hand. His hand is one big callus. He asks how long I've been playing, how many matches I've won, how many I've lost.

I never lose, I say quietly.

His eyes narrow. Mr. Fong pulls Mr. Brown aside and says: Don't do this, Jim.

Guy's asking for it, Mr. Brown whispers. Fool and his money.

You don't understand, Mr. Fong says. You are going to lose, Jim.

What the hell are you --? He's a kid.

That's not just any kid.

You must be crazy.

Mr. Brown walks back toward me and starts firing questions.

How much do you play?

Every day.

No -- how long do you play at one time? An hour? Couple of hours?

My father's back. He's got a fistful of hundreds. He waves it in the air. But Mr. Brown has had a change of heart.

Here's what we'll do, Mr. Brown tells my father. We'll play two sets, then decide how much to bet on the third.

Whatever you say.

We play on Court 7, just inside the door. A crowd has gathered, and they cheer themselves hoarse as I win the first set 6--3. Mr. Brown shakes his head. He talks to himself. He bangs his racket on the ground. He's not happy, which makes two of us. I feel as if I might have to stop playing at any moment, because I need to throw up.

Still, I win the second set 6-3.

Now Mr. Brown is furious. He drops to one knee, laces his sneakers. My father approaches him.

So? Ten grand?

Naw, Mr. Brown says. Why don't we just bet $500.

Whatever you say.

My body relaxes. I want to dance along the baseline, knowing I won't have to play for $10,000.

Mr. Brown, meanwhile, is playing a less relaxed game. He's suddenly junking, drop-shotting, lofting lobs, angling the ball at the corners, trying backspin and sidespin and all sorts of trickery. He's also trying to run me back and forth, wear me out. But I can't be worn out, and I can't miss. I beat Mr. Brown 6-2.

Sweat running down his face, he pulls a wad from his pocket and counts out five crisp hundreds. He hands them to my father, then turns to me. Great game, son.

He shakes my hand. His calluses feel rougher -- thanks to me.

He asks what my goals are, my dreams. I start to answer, but my father jumps in.

He's going to be No. 1 in the world.

I wouldn't bet against him, Mr. Brown says.

The talent assembled at Wimbledon is stunning. There's Jim Courier, ranked No. 1, fresh off two Grand Slam victories. There's Pete Sampras, who keeps getting better. There's Stefan Edberg, who's playing out of his mind. I'm the 12th seed, and the way I've been playing I should be seeded lower.

In the quarters I go up against Boris Becker, who's reached six of the last seven Wimbledon finals. This is his de facto home court. But I've been seeing his serve well lately. I win in five sets, played over two days.

In the semis I face John McEnroe, a three-time Wimbledon champion. He's 33, nearing the end of his career, and unseeded. The fans want him to win, of course. Part of me wants him to win also. But I beat him in three sets. I'm in the final.

I'm expecting to face Pete, but he loses his semi to Goran Ivanisevic, a big, strong serving machine from Croatia. I've played him twice before, and both times he's shellacked me in straight sets. I have no chance against him. It's a middleweight versus a heavyweight. The only suspense is whether it will be a knockout or a TKO.

As powerful as Ivanisevic's serve is under normal circumstances, in the final it's a work of art. He's acing me left and right, monster serves that the speed gun clocks as fast as 138 mph. But it's not just the speed, it's the trajectory. They land at a 75-degree angle. Each time he serves a ball past me, I say under my breath that he can't do that every time. The match will be decided on second serves.

He wins the first set 7-6. I don't break him once. I concentrate on breathing in, breathing out, remaining patient. When the thought crosses my mind that I'm on the verge of losing my fourth Grand Slam final without a victory, I casually set it aside.

In the second set Ivanisevic gives me a few freebies, makes a few mistakes, and I break him. I take the second set. Then the third. Which makes me feel almost worse, because once again I'm a set away from a Slam.

Ivanisevic rises up in the fourth set and destroys me. I've made the Croat mad. He loses only a handful of points. As the fifth set begins I run in place to get the blood flowing and tell myself: You want this. The problem in the last three Slams was that you didn't want them enough, and you didn't bring it, so this time you need to let Ivanisevic and everyone else in this joint know you want it.

Now Ivanisevic is serving at 4-5. He double faults. Twice. He's down love-30. He's cracking under the strain. He misses another first serve. I know precisely what's happening inside Ivanisevic's body. His throat is closing. His legs are quivering. But then he quiets his body and hits a second serve to the back of the box, a beam of yellow light that barely nicks the line. A puff of chalk shoots up. Then he hits another unreturnable serve. Suddenly it's 30-all.

He misses another first serve, makes the second. I crush a return, he hits a half volley, I run in and pass him and start the long walk back to the baseline. I tell myself, you can win this thing with one swing. One swing. You've never been this close. You may never be again.

And that's the problem. What if I get this close and don't win? The ridicule. The condemnation. I pause, try to shift my focus back to Ivanisevic. I need to guess which way he's coming with his serve. O.K., a typical lefty, serving to the ad court in a pressure point, will hit a bending slider out wide, to sweep his opponent off the court. But Ivanisevic isn't typical. His serve in a pressure point is usually a flat bomb up the middle. Sure enough, here he comes, but he nets the serve. Good thing, because that thing was a comet, right on the line. Even though I guessed right, I couldn't have put my racket on it.

Now the crowd rises. I call time, to have a talk with myself, saying aloud: Win this point or I'll never let you hear the end of it, Andre. Don't hope he double-faults. You control what you can control. Return this serve with all your strength, and if you return it hard but miss, you can live with that. You can survive that. One return, no regrets.

Hit harder.

He tosses the ball, serves to my backhand. I jump in the air, swing with all my strength, but I'm so tight that the ball to his backhand side has mediocre pace. Somehow he misses the easy volley. His ball smacks the net, and just like that, after 22 years and 22 million swings of a tennis racket, I'm a Grand Slam champion.

Later in the afternoon, trembling, I dial my father in Vegas.

Pops? It's me! Can you hear me? What'd you think?

Silence.

Pops?

You had no business losing that fourth set.

Stunned, I wait, not trusting my voice. Then I say, Good thing I won the fifth set, though, right?

He says nothing. Not because he disagrees or disapproves, but because he's crying. Faintly I hear my father sniffling, and I know he's proud, just incapable of expressing it. I can't fault the man for not knowing how to say what's in his heart. It's the family curse.

I'm at my house in Las Vegas, watching TV with Slim, my assistant. I'm in a bad way. Gil Reyes's 12-year-old daughter, Kacey, who broke her neck in a snow-sledding accident, isn't doing well after surgery. Meanwhile, my wedding to Brooke Shields looms. I think all the time about postponing it, or calling it off, but I don't know how.

Slim is stressed too. He was with his girlfriend recently, he says, and the condom broke. Now she's late. He announces that there's only one thing to do. Get high.

He says, You want to get high with me?

On what?

Gack.

What the hell's gack?

Crystal meth.

Why do they call it gack?

Because that's the sound you make when you're high. Your mind is going so fast, all you can say is gack, gack, gack.

That's how I feel all the time. What's the point?

Make you feel like Superman, dude.

As if they're coming out of someone else's mouth, I hear these words: You know what? F--- it. Yeah. Let's get high.

Slim dumps a small pile of powder on the coffee table. He cuts it, snorts it. He cuts it again. I snort some. I ease back on the couch and consider the Rubicon I've just crossed. There is a moment of regret, followed by vast sadness. Then comes a tidal wave of euphoria that sweeps away every negative thought in my head. I've never felt so alive, so hopeful -- and I've never felt such energy. I'm seized by a desperate desire to clean. I go tearing around my house, cleaning it from top to bottom. I dust the furniture. I scour the tub. I make the beds. I sweep the floors. When there's nothing left to clean, I do laundry. All the laundry. I fold every sweater and T-shirt, and still I haven't made a dent in my energy. I don't want to sit down. If I had table silver I'd polish it. I tell Slim I could do anything right now, anyf----- thing. I could get in the car and drive to Palm Springs and play 18 holes, then drive home and make lunch and go for a swim.

I don't sleep for two days. When I finally do, it's the sleep of the dead and the innocent.

I pull out of the French Open with a tender wrist I'd hurt a few weeks earlier. I go to London for Wimbledon but can't bring myself to practice. I tell my coach, Brad Gilbert, I'm pulling out of the tournament. I'm in vapor lock.

Brad says, What the hell does vapor lock mean?

I've played the game for a lot of reasons, I say, and it just seems like none of them have ever been my own.

After a loss in D.C. in July, I decide to shut down for the summer. Though we were married in April, Brooke is in Los Angeles working and I spend much of the summer in Vegas. Slim is there, and we get high a lot. I like feeling inspired again, even if the inspiration is chemically induced. I stay awake all night, several nights in a row, relishing the silence. No one bothering me. Nothing to do but dance around the house and fold the laundry and think.

Apart from the buzz of getting high, I get an undeniable satisfaction from harming myself and shortening my career. But the physical aftermath is hideous. After two days of being high, of not sleeping, I'm an alien. I have the audacity to wonder why I feel so rotten. I'm an athlete, my body should be able to handle this.

In the fall, I'm walking through New York's LaGuardia Airport when I get a phone call. It's a doctor working with the Association of Tennis Professionals. There is doom in his voice, as if he's going to tell me I'm dying. And that's exactly what he tells me.

It was his job to test my urine sample from a recent tournament. It's my duty, he says, to inform you that you've failed the standard ATP drug test. The urine sample you submitted has been found to contain trace amounts of crystal meth.

I fall onto a chair in the baggage claim area.

Mr. Agassi?

Yes. I'm here. So. What now?

Well, there is a process. You'll need to write a letter to the ATP, admitting your guilt or declaring your innocence.

Uh-huh.

Did you know there was a likelihood that this drug was in your system?

Yes. Yes, I knew.

In that case, you'll need to explain in your letter how the drug got there.

And then?

Your letter will be reviewed by a panel.

And then?

If you knowingly ingested the drug -- if you plead guilty -- you'll be disciplined.

How?

He reminds me that tennis has three classes of drug violation. Performance-enhancing drugs, of course, would constitute a Class 1, he says, which would carry a suspension of two years. However, he adds, crystal meth would seem to be a clear case of Class 2. Recreational drugs.

I say: Meaning?

Three months' suspension.

My name, my career, everything is now on the line. Whatever I've achieved, whatever I've worked for, might soon mean nothing. Part of my discomfort with tennis has always been a nagging sense that it's meaningless. Now I'm about to learn the true meaning of meaninglessness. Serves me right.

Days later I write a letter to the ATP. It's filled with lies interwoven with bits of truth. I acknowledge that the drugs were in my system -- but I assert that I never knowingly took them. I say Slim, whom I've since fired, is a known drug user, and that he often spikes his sodas with meth -- which is true. Then I come to the central lie of the letter. I say that recently I drank accidentally from one of Slim's spiked sodas, unwittingly ingesting his drugs. I ask for understanding and leniency and hastily sign it: Sincerely.

I feel ashamed, of course. I promise myself that this lie is the end of it.

The next April, I'm in Rome, lying on my hotel bed, resting after a match. The phone rings. It's my lawyers; they're on speakerphone. Andre? Can you hear us? Andre?

Yes, I hear you. Go ahead.

Well, the ATP has carefully reviewed your heartfelt assertion of innocence. We're pleased to say that your explanation has been accepted. Your failed test is thrown out.

I hang up and stare into space, thinking again and again: New life.

She spreads a towel on the sand and pulls off her jeans. Underneath she's wearing a white one-piece bathing suit. She walks out into the water, up to her knees. She stands with one hand on her hip, the other shielding her eyes from the sun, scanning the horizon.

She asks, You coming in?

I don't know.

I'm wearing white tennis shorts. I didn't think to bring a bathing suit to San Diego, because I'm a desert kid. I don't do well in the water. But I'll swim to China right now if that's what it takes. In just my tennis shorts I walk out to where Stefanie's standing. She laughs at my swimwear and pretends to be shocked that I'm going commando. I tell her I've done it since winning the French Open that way in June, and I'm never going back.

We talk for the first time about tennis. When I tell her I hate it, she turns to me with a look that says, Of course. Doesn't everybody?

I ask about her conditioning. She mentions that she used to train with Germany's Olympic track team.

What's your best race?

Eight hundred meters.

Whoa. That's a gut check. How fast can you run it?

She smiles shyly.

You don't want to tell me?

No answer.

Come on. How fast are you?

She points down the beach, at a red balloon in the distance.

See that red dot down there?

Yeah.

You'd never beat me to that.

Really.

Really.

She smiles. Off she goes. I go tearing after her. It feels as if I've been chasing her all my life, and now, six months after separating from Brooke, I'm literally chasing her. At first it's all I can do to keep pace, but near the finish line I close the gap. She reaches the red balloon two lengths ahead of me. She turns, and her peals of laughter carry back to me like streamers on the wind.

I've never been so happy to lose.

Stefanie tells me her father is coming to Vegas for a visit. Thus, the unavoidable moment has arrived. Our fathers are going to meet. The prospect unnerves us both.

Peter Graf is suave, sophisticated, well-read. He likes to make jokes, lots of jokes, none of which I get because his English is spotty. I want to like him, and I see that he wants me to like him, but I'm uneasy in his presence because I know the history. He's the German Mike Agassi. A former soccer player, a tennis fanatic, he started Stefanie playing before she was out of diapers. Unlike my father, however, Peter never stopped managing her career and her finances, and he spent two years in jail for tax evasion.

I should have expected it: The first thing Peter wants to see in Nevada isn't Hoover Dam or the Strip but my father's ball machine.

My father doesn't do well with people who don't speak perfect English, and he doesn't do well with strangers, so I know we have two strikes on us as we walk through my parents' front door. I'm relieved, however, to see that sport is a universal language, that these two men, both former athletes, know how to use their bodies to communicate, through swings and gestures and grunts. My father takes us to his backyard court and wheels out the dragon. He revs the motor, raises the pedestal high. He's talking nonstop, shouting to be heard above the dragon -- blissfully unaware that Peter doesn't understand a word.

Go stand there, my father tells me.

He hands me a racket, points me to the other side of the court, aims the machine at my head. Demonstrate, he says.

I'm having shuddering, violent flashbacks. Peter positions himself behind me and watches while I hit. Ahh, he says. Ja. Good.

My father clicks the dial until the balls are coming almost in twos. I don't have time to bring back my racket and hit the second ball. Peter scolds me for missing. He takes the racket, pushes me aside. This, he says, is the shot you should have had. You never had this shot. He shows me the famous Stefanie Slice, which he claims to have taught her.

My father is livid. He comes around the net, shouting: That slice is bulls--- ! If Stefanie had this shot, she would have been better off. He then demonstrates the two-handed backhand he taught me. With this shot, my father says, Stefanie would have won 32 Slams!

The two men can't understand each other, yet they're having a heated argument. I turn my back, concentrate on hitting balls. I hear Peter mention my rivals, Sampras and Patrick Rafter, and my father responds with Stefanie's nemeses, Monica Seles and Lindsay Davenport. My father then uses a boxing analogy, and Peter howls in protest.

I was a boxer, too, Peter says -- and I would have knocked you out.

I cringe, knowing what's coming. I wheel just in time to see Stefanie's 63-year-old father take off his shirt and tell my 69-year-old father: Look at me. Look at the shape I'm in. I'm taller than you. I can keep you at bay with my jab.

My father says, You think so? Come on! You and me.

Peter is trash-talking in German, my father is trash-talking in Assyrian, and they're both putting up their fists. They're circling, feinting, bobbing and weaving, and just before one of them throws hands, I step in, push them apart.

They're winded, sweating. My father's eyes are dilated. Peter's chest is beaded with sweat. They see, however, that I'm not going to let them mix it up, so they go to neutral corners. I turn off the dragon, and we all walk off the court.

At home, Stefanie kisses me and asks how it went.

I'll tell you later, I say, reaching for the tequila.

I don't know when a margarita has ever tasted so good.

Everyone travels to New York for my last U.S. Open. The whole team: Stefanie, our children, my parents, my brother Philly, Gil, my friend Perry Rogers, my coach Darren Cahill. We invade the Four Seasons, colonize my favorite Manhattan restaurant, Campagnola. The children smile to hear the applause as we walk in. To my ear, the applause sounds different this time. It has a subtext. They know this isn't about me, it's about all of us finishing something special together.

In the first round I play Andrei Pavel, from Romania. My back seizes up midway through the match, but despite standing stick straight I tough out a win. I ask Darren to arrange a cortisone shot for the next day. Even with the shot, I don't know if I'll be able to play my next match.

I certainly won't be able to win. Not against Marcos Baghdatis. He's ranked No. 8 in the world. He's a big strong kid from Cyprus, in the midst of a great year. He's reached the final of the Australian Open and the semis of Wimbledon.

And then somehow I beat him, in five furious, agonizing sets. Afterward I'm barely able to stagger up the tunnel and into the locker room before my back gives out. Darren and Gil lift me onto the training table, while Baghdatis's people hoist him onto the table beside me. He's cramping badly. A trainer says the doctors are on the way. He turns on the TV above the table, and everyone clears out, leaving just me and Baghdatis, both of us writhing and groaning in pain.

The TV flashes highlights from our match. SportsCenter. In my peripheral vision I detect slight movement. I turn to see Baghdatis extending his hand. His face says, We did that. I reach out, take his hand, and we remain this way, holding hands, as the TV flickers with highlights of our savage battle. We relive the match, and then I relive my life.

Finally the doctors arrive. It takes them and the trainers half an hour to get Baghdatis and me on our feet. Gil and Darren lead me out to the parking lot. It's two in the morning. Christ, Darren says. The car is several hundred yards away. I tell him I can't make it.

No, of course not, he says. Wait here and I'll bring it around. He runs off.

I need to lie down while we wait. Gil sets my tennis bag on the concrete, and I sit, then lie back, using the bag as a pillow.

I look up at the stars. So many stars. I look at the light stanchions that rim the stadium. They seem like bigger, closer stars.

Suddenly, an explosion. A sound like a giant can of tennis balls being opened. One stanchion goes out. Then another, and another.

I close my eyes. It's over.

No. Hell, no. It will never really be over.

The next morning I'm hobbling through the lobby of the Four Seasons when a man steps out of the shadows. He grabs my arm.

Quit, he says.

What?

It's my father -- or a ghost of my father. He looks ashen. He looks as if he hasn't slept in weeks.

Pops? What are you talking about?

Just quit. Go home. You did it. It's over.

He says he prays for me to retire. He says he can't wait for me to be done, so he won't have to watch me suffer anymore. He won't have to sit through my matches with his heart in his mouth. He won't have to stay up until two in the morning to catch a match from the other side of the world, so he can scout some new wonder boy I might soon have to face. He's sick of the whole miserable thing. He sounds as if -- is it possible?

Yes, I see it in his eyes.

I know that look.

He hates tennis.