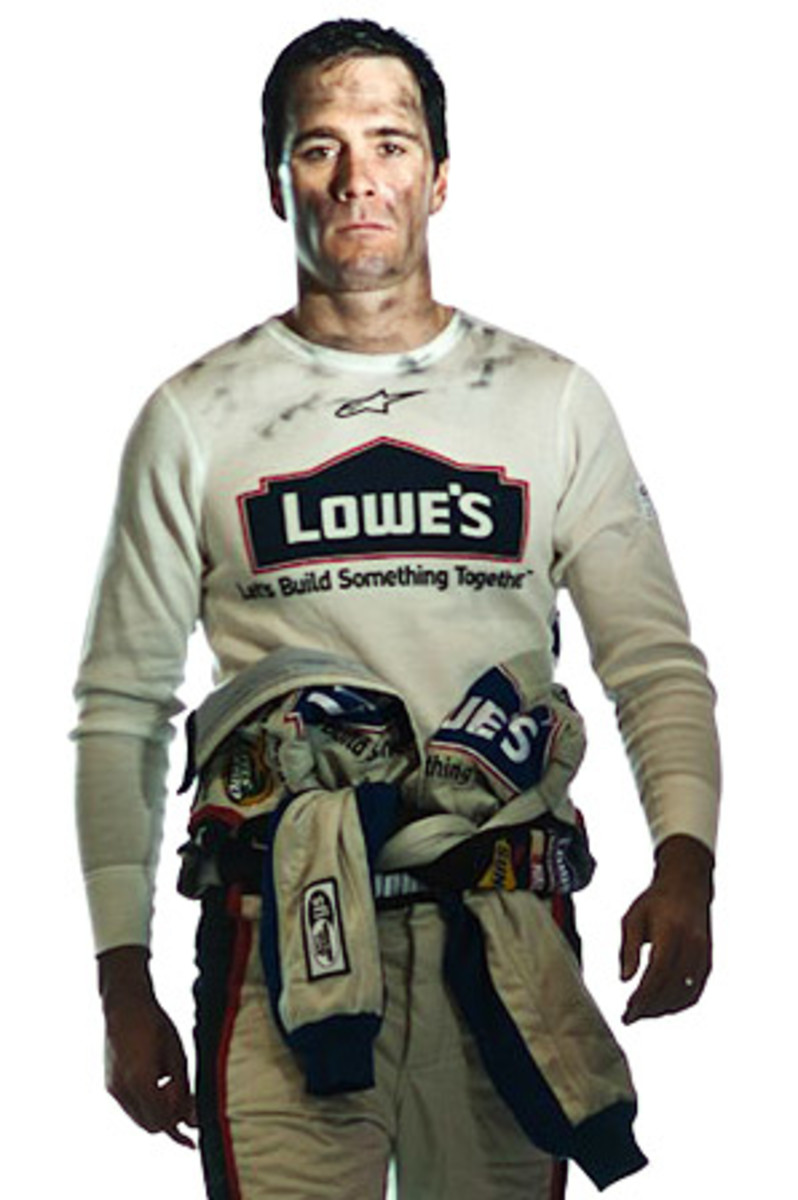

Jimmie Johnson

This article appears in the November 9, 2009 issue of Sports Illustrated.

Then, finally, here comes Junior Johnson. How he does come on. He comes tooling across the infield in a big white dreamboat, a brand-new white Pontiac Catalina four-door hardtop sedan. He pulls up, and as he gets out he seems to get more and more huge. First his crew-cut head and then a big jaw and then a bigger neck and then a huge torso, like a wrestler's, all done up rather modish and California modern, with a red-and-white candy-striped sport shirt, white ducks and loafers.

"How you doing?" says Junior Johnson, shaking hands, and then he says, "Hot enough for ye'uns?"-- Tom Wolfe"The Last American Hero Is Junior Johnson. Yes!" Esquire, March 1965

There are no lasts in American folklore. New times bring new heroes. And the Newest American Hero wears a khaki suit in a dark room under a bright spotlight. The smell of banquet steak lingers in the air. Jimmie Johnson hates wearing suits, of course. When this luncheon ends, he will not wait 10 minutes to tear the suit off. There's nothing interesting or strange about that. Jimmie Johnson drives race cars. Race car drivers do not like wearing suits that can catch fire.

What is interesting is that, uncomfortable or not, Jimmie Johnson looks just right in the suit. His tie does not dangle at an awkward angle. His shirt looks freshly pressed.

His 30-waist pants have creases that could cut through beer cans. He does not sweat under the lights. Every hair stays in place. The Newest American Hero looks like a young entrepreneur. He might be about to make an offer on your company.

"I feel lucky every day," Jimmie Johnson says. His clear voice fills the room; he has used a microphone before. His voice carries no detectable accent other than American. Later he will tell you that only sharks scare him more than talking in front of people, but there is no way the man talking is scared. He looks not merely confident; he looks and sounds as though he was born in a suit and spoke his first words at an awards banquet.

"I'm just so fortunate," he says, and then he casually mentions his sponsor (Lowe's, of course) and his racing team, led by crew chief Chad Knaus ("they are incredible"), and his wife, Chani ("my best friend"). There is applause, a short standing ovation.

That's when Junior Seau takes the stage. This is his fund-raiser -- the Junior Seau Foundation Teammates Luncheon, in San Diego in early October -- and the six-time All-Pro linebacker attacks it with the same ferocity with which he used to attack running backs for the Chargers. Junior bullies people in the crowd to raise their bids on auction items. Junior pokes fun at his mother for not exercising more and at his father for having droned on too long during the invocation. Nobody is out of his reach. Junior Seau is a runaway train, and now he looks over Jimmie Johnson, measures him.

"I don't get you, man," Junior shouts. "You're up here, and you're all humble and meek and stuff. And then you get on the racetrack, and you're the Man! You're out there racing and slamming into cars. You've won three Super Bowls, man. You are the best ever. Thebest ever! And then you're up here, man, and you're like quiet and nice. What's that all about?"

Jimmie Johnson looks at Junior Seau awkwardly and shrugs his shoulders.

"That's what I'm talking about," Junior Seau shouts even louder. "WHAT'S WITH YOU, MAN?"

Seven years old. Jimmie Johnson -- for his Christian name is Jimmie, not James or even Jim -- knew that he could not take the double jump on his motorbike. He was too young, too green, too scared, and yet the voice of his hero echoed in his ears. Rick Johnson was the baddest man in El Cajon, Calif. Rick would win seven national motocross championships. Rick was 18 and the coolest thing going. Jimmie made himself believe that he and Rick were cousins, even though he'd been told they were not related. Jimmie needed to believe he had some of Rick in him.

"If you make that jump," Rick told him just before the under-10 race, "you will win! Do you hear me? You will win!"

Jimmie wanted to win. For himself. For Rick. But he was seven years old. He did not try the jump on his first lap or his second. The third time he approached the double jump, he saw Rick standing on the track -- on the track! -- and Rick was flicking his right wrist, a sign to pound the throttle. Jimmie sped up. The hill approached too fast. Jimmie would remember feeling something -- fear, certainly, but something else too, something harder to describe. Jimmie rushed up the hill, impossibly fast, and his bike took off, and it cleared the valley, and it landed softly on the other side. Impossible! Absurd! Seven years old! A perfect landing on the double jump! Never been done!

Then Jimmie rode off the track and fell off his bike.

"You hurt him!" Jimmie's father, Gary, yelled at Rick as he rushed toward his son. "You pushed him too fast."

"No!" Jimmie shouted as he dusted himself off. "I'm fine. I'm ready to go again."

"What happened?" Rick asked. "Why did you ride off the road?"

Jimmie shrugged. "Well," he said, "I had my eyes closed."

The Vanilla Thing. That's what Jimmie Johnson calls it. He has spent too many hours thinking about it. How could people see him as vanilla? He grew up in a trailer park. He jumped motorbikes and motorcycles, flipped off-road vehicles in the desert, drove trucks and hot rods and buggies. He tempted fate at every stage of his life. He worked his way up in the most American way, using his charm and talent and making friends. Now, at 34, he drives in the NASCAR Sprint Cup Series -- "200 miles per hour with 40 other maniacs," as Rick Johnson describes it -- and nobody in the series drives better. Jimmie Johnson has won three Sprint Cup championships in a row, and with a 184-point lead after seven Chase races this year, he's on course to win his fourth straight, something no one has ever done.

Jimmie Johnson has won 40 Cup races over the last six years, more than have been won by Dale Earnhardt Jr., Mark Martin, Carl Edwards and Denny Hamlin. Combined. Also more than Tony Stewart and Jeff Gordon combined. As Gordon says, "No one is even close." Or as Martin says, "He's Superman." And it grows more apparent, year after year, victory after victory, championship after championship, that no one who has climbed into a stock car -- not the good ol' boys or the moonshiners, not the intimidators or the kings, not the fireballs or the silver foxes or the men named Cale -- has ever driven it better than Jimmie Johnson.

Isn't this the American Dream come to life? Well, isn't it? Poor kid makes good. Thrill-seeker testing the limits. Jimmie Johnson can't help but see it that way. And still: the Vanilla Thing. He knows he bores people. He hears the boos that have followed him in his career. He catches the groans from the racing writers when he walks into the pressroom. He could not help but notice that before the season began, those racing writers -- a bit too enthusiastically, perhaps -- named Carl Edwards the favorite to win the championship this year. Carl Edwards? Johnson had won three in a row. How could he not be the favorite? But he knows: It's the Vanilla Thing.

"Go stand next to your refrigerator, it's more quotable than Jimmie Johnson." That was a line in what was actually a positive story in TheTampa Tribune.

"The dude is more consistent than Wonder Bread -- and about as colorful." That was the review in the Orlando Sentinel.

"It's hard to find NASCAR fans who admit they love Jimmie Johnson." That was the lead for a story in the Las Vegas Review-Journal.

"If Jimmie would just get out of the race car and just slap someone one time," NASCAR pitchman and track owner Bruton Smith announced, "that would help a lot."

Johnson says he won't think about the Vanilla Thing anymore -- he can't think about it, he has races to win -- but he can't quite let it go, either. People seem mad at him because he's not . . . well, what? He's not Junior Johnson, Wolfe's Last American Hero, the moonshiner driving the dirt roads through the night like a demon. He's not Dale Earnhardt Sr., the man in black, his hard look frozen in other drivers' rearview mirrors, the look that said, "Get out of my way, or I'll run you into a wall." He's not Cale Yarborough, the only other man who's won three straight Cup championships, Cale, who wrestled alligators and boxed in the Golden Gloves and took on both the Allison brothers in a brawl in the infield at Daytona. He's not Richard Petty, the King, magnanimous, irrepressible, 200 victories, always in his cowboy hat and sunglasses, speaking in that friendly Southern accent that never left Level Cross, N.C.

No, he's plain old Jimmie Johnson, adrift in a sea of similarly named sportsmen -- the brash football coach who led the Cowboys to dominance (Jimmy Johnson), the Hall of Fame cornerback (Jimmy Johnson), the Northwestern quarterback who made the College Football Hall of Fame (Jimmy Johnson), the NFL tight end (Jimmie Johnson), the late defensive coordinator of the Philadelphia Eagles (Jim Johnson), the relief pitcher for the Baltimore Orioles (Jim Johnson) and the onetime East Carolina football coach (Jim Johnson), not to mention a couple of hockey players named Jim Johnson.

"Is Peyton Manning that interesting?" Johnson asks quietly. "Tom Brady? Derek Jeter? How about Tiger Woods? I guess that's what I don't get about the Vanilla Thing. I guess I've always tried to do the right thing. I thought that's what people wanted."

He shakes his head. It doesn't matter. He has plenty of fans -- "I'm anywhere from second to fifth in popularity, according to our numbers," he says -- and, anyway, what difference does it make? He has a great sponsor (Lowe's, of course) and a great team ("Those guys work so hard,") and a great wife ("I couldn't do it without Chani"). And he's winning. There's nothing in the world like winning.

Eighteen years old. Jimmie Johnson sat on a rock near his truck, or rather the twisted metal sculpture that had only hours before been a full-sized Chevy pickup truck. He thought hard about what kind of man he wanted to become. It was a good time to think. He was lost somewhere near El Arco, Mexico, somewhere on the Baja California peninsula, somewhere in the middle of nowhere. How did he get there? Well, technically, he knew exactly how he had gotten there: He had been racing in the Baja 1000, he had been driving for 20 straight hours on rocks and ridges, and then he'd hit a smooth road, too smooth, and nodded off for an instant. Just an instant. The turn came too fast, the truck hit a rock, the truck jumped the edge, and Jimmie knew that he and his codriver, Tom Geivis, were going to die. They were falling off a mountain. Goners. Only, no, they lucked out. They flipped and flipped, again and again, too many times to count, until the truck crashed in a bed of rocks. Geivis was knocked unconscious but felt O.K. when he got up. Johnson was conscious through it all.

As he sat on that rock -- and he sat there for a long time because it took a full day for a helicopter to spot them -- Johnson had something like a revelation. He could die in a race car. O.K., it might not be the light from heaven flashing about Saint Paul, but it felt pretty important to Jimmie Johnson at that moment. He had always known the danger, and yet he had never known the danger at all.

And in that moment, as rain drizzled in the cool night, he made himself a promise. He would not be reckless. He would not be rash. He would do everything he could to take danger out of race car driving.

Jimmie Johnson drives a golf cart from hole to hole. He's at the Jimmie Johnson Foundation golf tournament in Del Mar, Calif., early last month, and he must mingle. This means one thing: More or less every person he sees will ask him if he plans to surf on top of the cart.

"Goin' surfing, Jimmie?" one golfer asks.

"Watch out for big waves," says another.

"Better get your helmet," says a third.

Johnson smiles each time someone says it, as if it's brand new. Three years ago, only a few days after he won his first Cup championship, he was horsing around at a celebrity golf tournament. He decided (and he readily admits that his decision-making skills might have been slightly impaired by an adult beverage or two) that it would be fun to surf on top of a moving golf cart. This led to him falling off, busting his lip and breaking his wrist. This led to him feeling foolish. This led to him telling people that he was inside the cart when he fell. And that led to his spokesperson, Kristine Curley, phoning him and saying, "Jimmie, the Associated Press called. Were you actually on top of the cart when you fell off?"

He copped to the crime. Word went out. Jimmie Johnson had a few moments as America's sporting goofball.

"I was embarrassed when it happened," he says, "because I thought I had to be perfect. It took me a while to realize, Hey, I can't be perfect. I'm really not embarrassed by it now. It was stupid. I do a lot of stupid stuff. I really don't mind people talking about it. The thing that amazes me is how many people still talk about it."

Maybe people still talk about it because it's the one funny thing they know about him, the one bit of humanity and imperfection they cling to in Jimmie Johnson's windstorm of sponsor-speak ("Lowe's has just treated me so well") and team ("Chad and the guys are amazing") and wife ("I couldn't do any of this without Chani").

"I'm just not good at telling stories," Jimmie says, "and I'm terrible at telling jokes." Only then he tells some stories and a couple of jokes. And, of course, he's as good at that as he is at wearing suits and speaking in front of crowds. Did you know Jimmie Johnson gets carsick when he's not driving? He has suffered from chronic motion sickness his whole life. He gets sick on boats and on merry-go-rounds, and there have been many times when he was being driven somewhere and had to ask the driver to pull over so he could throw up out the window.

That's funny: The world's greatest stock car driver gets carsick. "Really?" Johnson asks. He tells about the time in Charlotte (where he and Chani live year-round) when he ran out of gas on the way to the airport, and people angrily honked their horns and glared as he stood helplessly on the side of the highway, and not one person recognized him and shouted out the window, "Hey, it's harder without a pit crew, isn't it?" He talks about the safari he went on in South Africa, and the crazy diet he just finished (he had to wake up every three hours to take a protein shake), and how he really wants to jump out of a plane but Chani has told him, "You go ahead, but I won't be here when you hit the ground."

He talks about his more fanciful dreams. He wants to start his own ice cream brand. He already has the name of the first flavor -- Jimmie Johnson's Nuts & Bolts. ("The only problem," he says, "is I don't really like nuts in my ice cream.") He wants to create a new kind of racing video game. ("I have a lot of really cool ideas," he says.) He and Chani want to own their own vineyard. ("I wouldn't want to just buy the grapes to make wine. What's the point of that?") He thinks about writing a book, but it would have to be a series of short stories because he reads in bursts. It's no wonder that people who know Jimmie Johnson cannot understand the public persona, and the public knows nothing about this Jimmie Johnson.

"You have to understand something about racing," says Ivan (Ironman) Stewart, one of the legends of off-road racing and another hero of Jimmie Johnson's. "Racing people can talk to other racing people. We know what it's like out there. We know the feeling of being in a race, the way it looks, the way it sounds, the way it smells. Jimmie is a racing guy."

A racing guy. People can't help but wonder, What's left for him to conquer? Once you've won your fourth straight championship, is it that important to win a fifth? A sixth? At some point does it all lose its thrill?

"Jimmie just likes to go fast," Rick Johnson says. "That's what drives him. That will never get boring for him."

Jimmie Johnson nods. "I know this will sound like a cliché, but there's always another challenge," he says. In 2008, when the undefeated New England Patriots played his hometown Chargers, Johnson was asked which team he wanted to win. "The Patriots," he said. Later, his publicist asked why he would say that. Johnson shrugged.

"Perfection," he said. "I always root for perfection."

Twenty-four years old. Jimmie Johnson was driving his black Alltel car in a Busch Series race at Watkins Glen, in the heart of New York State, when a most unexpected thing happened: His brakes went out. It doesn't matter if you're Jimmie Johnson, Junior Johnson or Magic Johnson -- when you push down on the brakes and the car doesn't slow, there's nothing to do but hold on tight and hope against hope that you don't hit anything too hard.

Johnson pulled his car hard to the right, and his tires kicked up grass and mud. But the car didn't slow down any. The only thing that did slow down was time. The next two seconds... Johnson would say a million thoughts coursed through his mind. Then he saw the wall straight ahead, the white wall, concrete for sure, and his body went limp. There was nothing left to do except hit that wall. His car went airborne. Johnson would remember the loudest thought pounding in his head: This is really bad.

And then the car hit the wall. It was not concrete, though. The guard rail had been cushioned by giant white blocks of Styrofoam. After the car hit, Johnson felt shooting pain in his neck. But this comforted him. Dead people don't have pain in their necks. He struggled to get his helmet off; his arms worked! He tried to get out of the car; his legs worked too! He climbed to the top of the car and heard the most enormous sound. Cheering. Wild, unchained, irrepressible cheers. And he raised his arms high above his head like Rocky after he reached the top of the museum steps. There was no lesson in this crash except, perhaps, the greatest lesson of all: He was alive!

Jimmie Johnson sits in the Tonight Show green room. He has the dressing room right across from Christian Slater's. He will race golf carts with Conan O'Brien in a couple of hours. His spokesperson, Curley, is admonishing him for wearing sneakers and no jacket. Johnson says, "This is my image. I worked hard to create this image." And then, as silence fills the little dressing room, he wants to work.

"Name a driver," he says. "Go ahead. Name any driver."

Mark Martin.

"Mark will be the guy on the bottom of the racetrack grinding it out. When he comes on you, you just let him go past because you have so much respect for how hard he works and how much he will grind it out."

He is engaged now. Friends know there are times when you have to leave Johnson alone, when he is beating himself up for a mistake or trying to figure out what went wrong or just crawling into himself. But now he's in the moment. He's racing.

Dale Earnhardt Jr.

"Junior, if he gets a chance, will pass you up on the outside. That's what he wants to do. He wants to pass you on the outside."

Johnson closes his eyes now. He's visualizing. He spends hours visualizing the track, the line he's on, the drivers around him. He never misses a chance to test the car. He never leaves an empty moment. "He will be in bed just staring into space," Chani says, "and I'll say, 'What are you doing?' And he will say, 'Driving laps.' "

Jeff Gordon.

"Oh, man. Jeff will always put you in a position where you have to make a decision. That's what he's so good at. He's so calculating, and he's going to put you in a position where you have to decide what to do."

His voice is getting louder, more excited. The 38-year-old Gordon is Johnson's mentor. At a drivers' meeting years ago Johnson, who was racing in the Busch Series, approached Gordon to ask for advice. They hit it off. Before long, team owner Rick Hendrick wanted to add another driver, and Gordon pushed hard for Johnson. And since then Johnson has spent time watching Gordon, studying him, copying him, asking him for advice (and, inevitably, beating him on the track). He loves Jeff Gordon. And he loves beating him.

Kyle Busch.

"Kyle is undependable. You can't be entirely sure what he's going to do. He's really aggressive. He's going to put pressure on you."

Jimmie Johnson.

He shrugs. People have many opinions as to why he's so good at driving. Some say it's because of the loyalty he inspires in his team. Some say it's because of the preternatural calm he displays no matter the situation. "I just think he works at it all the time," Chani says. "He's so hard on himself, and he just thinks all the time about how to get better."

"Aw," Jimmie Johnson says as he walks to the stage, "I'm easy to figure out."

Thirty-four years old. Jimmie Johnson stands in the Tonight Show parking lot after the taping. There was some sort of mix-up with his car. The Tonight Show people are mortified, and several of them are on cellphones at once. They are all speaking loudly. Every couple of minutes someone wanders over to Johnson to apologize. He shrugs. "It's nice out here," he says.

It is nice. The sun sets over Burbank, and there's a pleasant chill in the air, and somehow the conversation turns to sharks. Turns out Johnson knows quite a bit about sharks. He talks about the sharks he has seen up close. Lemon sharks. Hammerhead sharks. Thresher sharks. He talks about how he would like to see a great white someday. He tells how the first time he went shark diving, he dropped to the ocean floor, and he held on to a rock, and he felt absolute panic as sharks swam over him. Not long after that he went back.

"Why would you do that?" he is asked.

"Because I'm absolutely terrified of sharks," he says. "So I had to go down there. I had to face my fear."

He smiles and nods as another Tonight Show person walks over to say it will be just a few more minutes before the car arrives. The Tonight Show people have been around celebrities. They have been around sports stars. And it's clear: They don't know what to make of Johnson's calm as he waits for a car that should have been here 25 minutes ago.

"Why do you have to face your fear of sharks?" he is asked. "What difference does it make?"

Johnson glances up. "What do you mean?" he asks.

"I mean, what difference does it make? You're a famous race car driver. You're not going to run into any sharks. Why do you have to face your fear of sharks?"

Jimmie Johnson shrugs. He looks curious. "I never really thought about it," he says. And then, finally, the car arrives, a black town car, and the Newest American Hero smiles. He waves off the flood of apologies from the Tonight Show crew, and he promises to do his best in that weekend's race. He climbs into the backseat, and he looks like anybody else as he leans close to the window, just in case the ride makes him sick.