Remembering the game that changed football -- for the better

November 2009 marks the all but forgotten centennial of a moment that could have ended football in America, but instead forced the sport down a different, better path.

Football was so gruesome at the turn of the century that in 1905 President Roosevelt himself demanded the sport clean itself up. The notorious flying wedge was banned, but by ought-nine -- as they said back then -- it was still a brutal battle royal. The New York Times summed up the season's championship match as "an indescribable tangle of bodies, arms and legs."

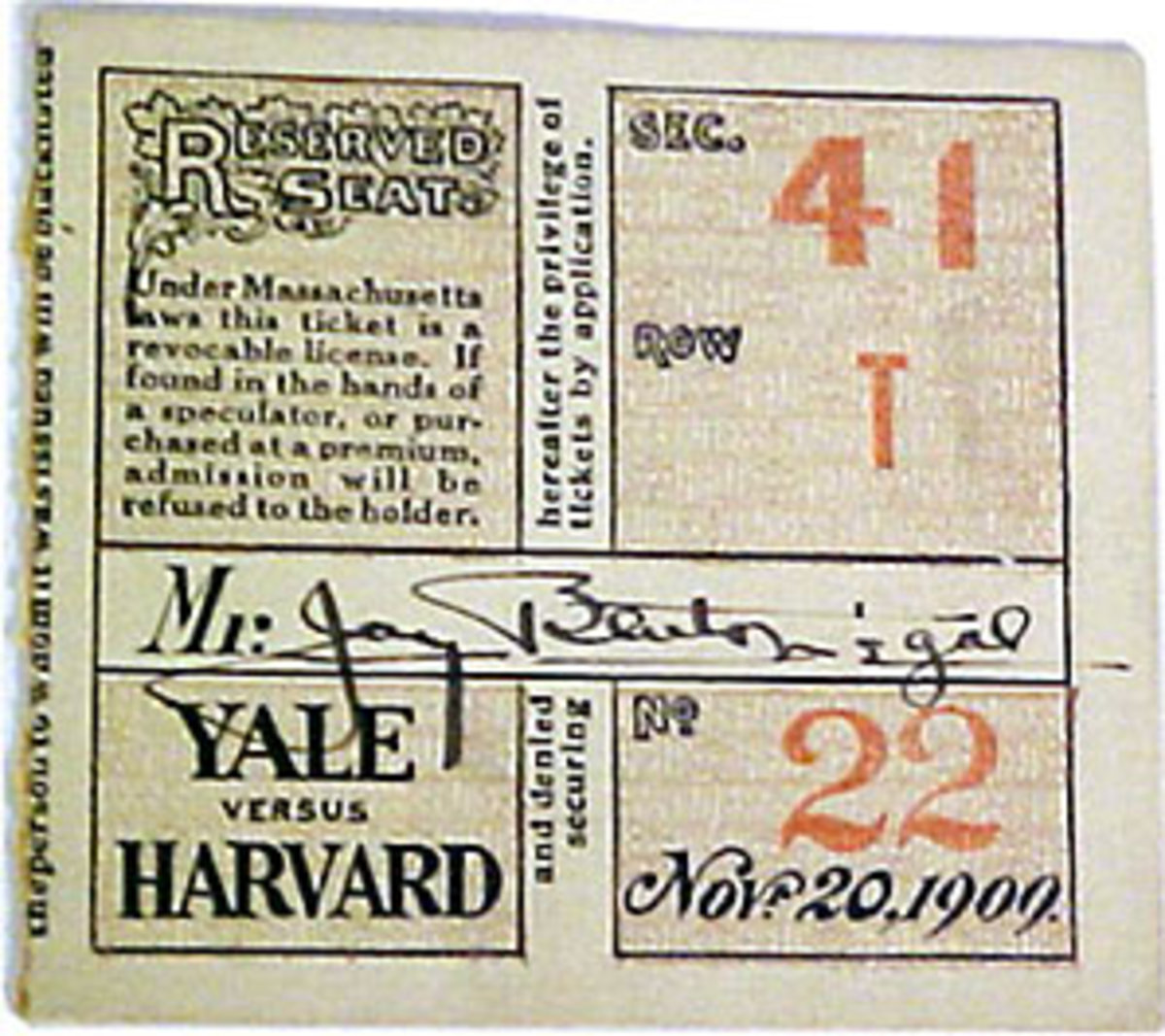

That game, played on November 20 and arguably worthy of the "game of the century" label, pitted undefeated Yale and Harvard against each other. In then typical fashion, there were no touchdowns. In fact, when Yale won 8-0, it finished its whole season without letting up a score. The forward pass had been legalized in a limited fashion, but football remained mostly pounding scrimmage; few players wore helmets, and a close observer declared that as the Harvards and Yales pummeled each other, "It was the most magnificent sight ... Every lineman's face was dripping with blood."

But the great game of a hundred years ago was overshadowed by greater carnage at other major universities. Three weeks before, when Harvard played at West Point, an Army lineman named Eugene Byrne was killed. Then two Saturdays later, against Georgetown, in the nation's capital, Archer Christian, the University of Virginia's star halfback, met his death. The Chicago Tribune reported twenty-six players were killed on the gridiron that year. How long would America allow its youth to perish for a silly game?

The president of Stanford, disgusted, called football "rugby's American pervert." Colonel John Mosby, who as the fabled Confederate "Gray Ghost" had seen his share of death and mayhem during the Civil War, was an even more fascinating critic. The old warrior called football "a barbarous amusement" that "develops the brute dormant in man's nature and puts the player on a level with ... a polar bear."

In the face of such withering widespread criticism, the new NCAA was forced to find ways to reduce the game's dangers. Although some of the game's powers -- not unlike the smug football aristocracy in the Bowl Championship Series today -- were relatively content with the gory status quo, other colleges took a more progressive approach. Rules liberalizing the forward pass were instituted for the 1910 season, and soon it became the weapon that opened up a safer game.

Of course, some things never change for the better. Canny old Colonel Mosby also made this point: "It is notorious that football teams are largely composed of professional mercenaries who are hired to advertise colleges. Gate money is the valuable consideration."

Yes, college football was already an academic fraud when the Gray Ghost wrote that exactly a century ago, and although the NCAA could clean up the game on the field, it never has figured out how to manage the other abuses.