Jorgensen pays critics no mind

Inked on the inside of Scott Jorgensen's right forearm, the words "no mind" sum up pretty well the 27-year-old mixed martial artist's view on life.

"It's my mantra. It keeps me going," said the bantamweight, who meets Japan's Takeya Mizugaki on Saturday in Las Vegas (10 p.m. ET, Versus). "Come the night of the fight, it doesn't matter how many people are in the stands, who's watching, what the implications are. In the end there's two guys standing in a cage. Both of 'em want to win. How bad do you want it? How much will you let the outside world affect that?"

Jorgensen, a three-time Pac-10 champion wrestler, embraced the idea after reading Hagakure: The Book of the Samurai, following his senior year at Boise State University in 2006 -- though he didn't necessarily need Eastern philosophy to overcome adversity.

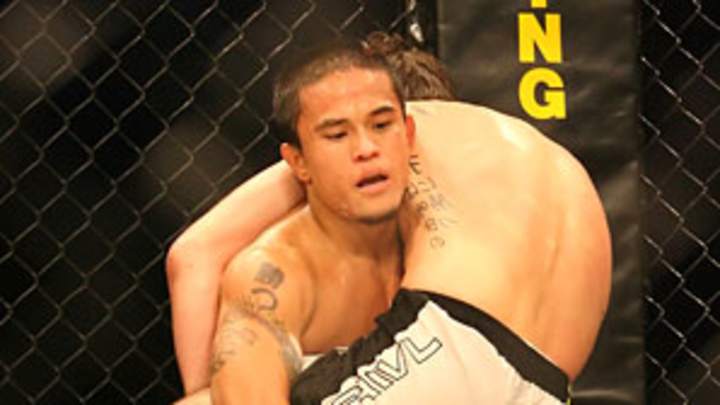

As a high school sophomore in Alaska, where he lived before moving to Idaho for his final year to improve chances of earning a scholarship to a top wrestling program, Jorgensen was diagnosed with vitiligo, a relatively common disorder that destroys or weakens pigment, causing white spots or patches to appear on the skin. It is said that vitiligo isn't so much a physical disorder as a mental one because of the self-esteem issues that are associated with it. Jorgensen couldn't cover up what was happening, not if he was going to be any kind of competitor. Not of he intended to be honest about who he was. So he did his best to let it go, even as patches climbed both arms by the time he was a senior.

(Jorgensen went undefeated during his final high school wrestling season -- no opponent came within eight points of him -- to win the Idaho state tournament.)

Outside of one laser treatment advocated for by his mom, the 5-foot-4, 135-pounder visited a doctor just once about the condition.

"I think he embraced it," said former WEC featherweight champion Urijah Faber, who befriended Jorgensen while coaching at conference rival UC Davis. "The way he dresses, the way his body is, he's a colorful cool-looking dude. I don't think it's been an issue in any way for him. I think it kind of blends in with his style. He's kind of a little work of art."

For many people with vitiligo it's not that simple, Jorgensen acknowledged. Increased television exposure for his fights inside the WEC has invariably led to correspondence from sufferers and parents of sufferers. Often, they ask for encouraging notes.

"The confidence I've gained over all my years wrestling and training, I know what makes a person," he said. "It's not your appearance. It doesn't matter what you look like. If my having white spots can help somebody, then great."

Against Mizugaki, one of the top bantamweights in the world, the aggressive Jorgensen faces perhaps the most important test of his young career. Should things fall in line Saturday at WEC 45, Jorgensen could get former champion Miguel Torres in March. That's looking ahead, though, and he isn't about to do that.

Jorgensen has always grappled with being overly aggressive. Winning wasn't enough. He had to dominate. There were never enough pins or points. For the most part, it served him well, but there are moments when ambition was costly. During his junior year at the NCAAs, a mistake against an unseeded kid from Eastern Michigan in the final 45 seconds of a match he was up cost him the win. That attitude, while making Jorgensen one of the bantamweight division's most exciting fighters, has similarly hampered him in MMA. Against Antonio Banuelos, Jorgensen was angered when he took a shot to the eye and couldn't see until the middle of the second round. He responded by slugging it out, and the split decision count for Banuelos continues to bother him.

Yet Faber, who helped Jorgensen get into MMA and routinely offers him advice on all aspects of the job, and U.S. Olympic wrestler Joe Warren see Jorgensen's get-after-it mentality as one of his best traits.

"He just trains hard and tries to get his technique better everyday, and not worry about what the other guy is doing," said Warren, who spent a week in Colorado with Jorgensen in preparation for Mizugaki (12-3-2). "That guy is going to have to fight him. He's not worried about fighting that guy."

Mizugaki, a quality boxer with a big frame for 135, should expect Jorgensen, a scrambler, to fight. Other than that, he won't walk into the cage with much of a plan. At a time when MMA has never been more competitive, studying the opposition seems mandatory. Not for the instinct-reliant Jorgensen.

In 2003, he passed on living at the U.S. Olympic training center in Colorado Springs, Colo., to train under Terry Brands for remaining in Boise and fighting. "I was happy doing what I was doing in wrestling," Jorgensen said, "but not as happy as I should have been."

He felt drawn to MMA. During his freshman year he met former UFC lightweight champion Jens Pulver, also a Boise State wrestler. Jorgensen toured the Pac-10 conference wearing fight apparel at wrestling tournaments, and trips to Sacramento usually meant a powwow Faber.

"He's got a pretty good business mind," Faber said.

Taking a cue from "The California Kid," Jorgensen is attempting to establish Twisted Genetics, a fight team in Boise and branded MMA apparel line.

"Some are born to build, to discover, to heal; and there are those born to fight," reads a quote on the team's Web page. "They fight for themselves, their families, their God. It is their nature, it is their genetics. Those that cannot understand label it abnormal, deviant ... twisted. It is our twisted genetics that compels us; it is what separates us from them."