How Triton Financial used athletes to attract clients, defraud investors

Triton Financial, an Austin, Texas-based investment firm which boasts prominent ties to the sports world -- including a sponsorship deal with the Heisman Trophy Trust; a three-year contract for a PGA Champions Tour event, the Triton Financial Classic; and a roster of former Heisman Trophy winners and NFL players that were employees of the company -- has been sued in a civil action by the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission for defrauding investors in a multimillion-dollar insurance scam, according to documents filed yesterday at Austin federal court. In connection with the complaint, Triton and its CEO, Kurt Barton, consented to an injunction to put the company into receivership.

The SEC complaint alleges that Triton and Barton had raised more than $50 million for at least 40 limited partnerships since 2004, and that the firm's insurance vehicle at the center of the complaint, Triton Insurance, had raised roughly $8.4 million from 90 people.

"Mr. Barton has consented to a receivership, which essentially means that the receiver now takes over the business," Toby Galloway, an attorney for the SEC's Fort Worth regional office, said. "Mr. Barton is out and will no longer be operating these businesses or stiff-arming investors."

Barton could not be reached for comment on his cell phone yesterday. His attorney, Joe Turner, said the following in a brief press release: "[Barton] intends to work closely with the receiver in an effort to ensure that the investors, many of whom are friends and relatives, do not lose their money."

SI.com has also learned that Triton is the target of a separate class-action lawsuit that was filed on Dec. 14 and newly amended yesterday in Travis County (Texas) District Court. The suit alleges that Barton solicited $12 million from investors, including the named plaintiff, Ryan Shapiro, for the purchase of an underperforming insurance company that it never bought, instead illegally using the money collected to pay bills or other Triton clients under the guise of "returns" on previous investments. The SEC's complaint echoes that same claim.

"What we know is that people trusted their entire financial future to this man and to this company," says Jason Nassour, an Austin-based attorney who is part of Shapiro's legal team. "Kurt Barton should be ashamed of himself on any number of levels."

According to the SEC, the government investigation began after SI first investigated Triton in a March article. SI had discovered several significant misrepresentations, among them false claims of SEC registration (Barton said he had registered in October 2008, whereas the SEC and Texas State Securities Board both attested that none existed); wild exaggerations of the value of Triton's assets under management (Barton touted the total as "over $300 million," while government forms and the firm's then-general counsel revealed that the company in actuality had less than $25 million); and an employee, former NFL quarterback Jeff Blake, who had e-mailed an advertisement -- claiming a jaw-dropping average of 32 percent annual returns on Triton investments over the past five years -- to 102 current and former NFL players without any of the disclaimers legally required by the SEC.

Once the Texas State Securities Board (TSSB) began looking into Triton -- which had been registered as an investment adviser since 2006 -- and requesting documents and information, the SEC complaint says that Barton sent the TSSB "altered and fabricated documents" in an attempt to "conceal the true number of investors and the true amounts of funds raised." The TSSB's own hearing will be held on Feb. 25, 2010.

The SEC complaint also notes that Triton "made most of its offerings through personal contacts," utilizing a sales force that employed football players -- all of whom conspicuously left the company in recent months. Galloway and the SEC's complaint both declined to specifically accuse any salesmen of wrongdoing, but Rose Romero, director of the SEC's Fort Worth office, said that "by associating with former football stars, [Triton was] able to build a facade of legitimacy and gain investor trust."

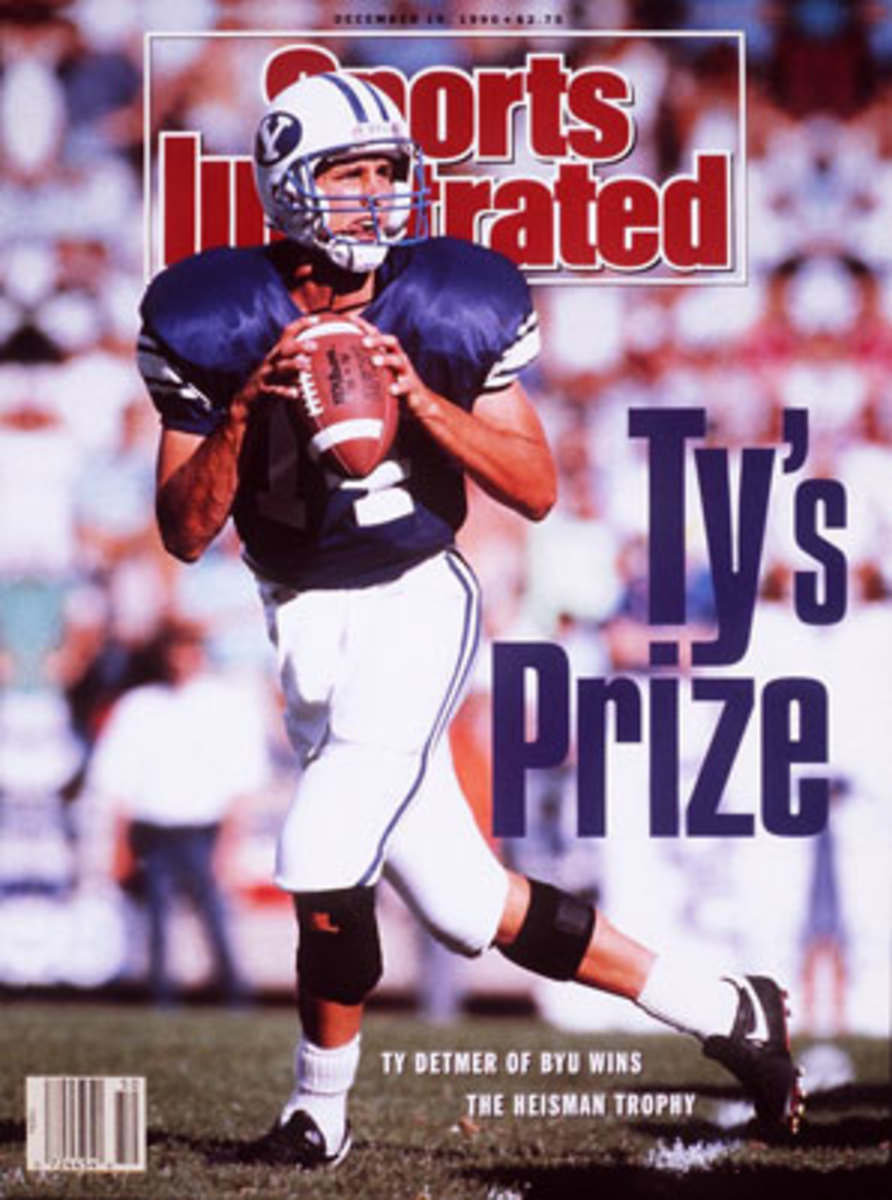

Former employees include Heisman Trophy-winning quarterback Ty Detmer, a longtime friend of Barton and the former "senior vice president of athlete services"; Blake, a former "director of athlete services"; free-agent NFL quarterback Koy Detmer, Ty's brother; former University of Texas quarterback Chance Mock, who left at the start of the year; and Heisman Trophy-winning quarterback Chris Weinke, who was promoted to Ty Detmer's position after Detmer's departure this fall but then also left in the following weeks. A series of testimonials starring Heisman-winning running back Tony Dorsett has also been removed from Triton's Web site. Triton's general counsel and chief compliance officer, David Tuckfield, also left the company in recent months.

"Ty only learned of the SEC's interest in Triton a few weeks ago, and has assisted the agency in its investigation," Ty Detmer's lawyer, Spencer Barasch, told the media. "If the allegations of the SEC's lawsuit are true, Ty, along with his peers, were greatly misled and Ty will continue to cooperate with the SEC in its investigation, if asked to do so."

Messages left with Blake, Weinke, Dorsett and Tuckfield yesterday have not been returned.

The lawsuits are the latest chapter in a saga that has been filled with deception and drama. On the afternoon of Dec. 11, a distressed Triton investor, Christine Cayton, entered the company's offices and allegedly threatened Barton with a handgun. Cayton -- a 46-year-old housewife who was dressed in her pajamas, on prescription stress medication and holding a bottle of wine -- had the weapon forcibly taken from her when she reportedly reached back into her purse for bullets. (Cayton was jailed and posted bond and now awaits trialon Jan. 4 on charges of aggravated assault with a deadly weapon.)

A week before that, on Dec. 4, Travis County court records show that Cayton had filed her own lawsuit alleging that Triton had committed statutory fraud in March by using "false representations of fact" and "false promises" to convince her to invest her family's $125,000 life savings. Cayton also claims that Triton began purposefully avoiding her questions and only arbitrarily sent her dividends.

"Hopefully, [Cayton] will receive the proper treatment and counseling necessary to prevent this from happening again," Barton would later say in a statement. "We would like to take this opportunity to assure our clients that we will continue to provide the same great level of service that they received prior to this unfortunate event."

Says one of Cayton's securities lawyers, Jim George, "All I'd like to say is that it appears that there are a lot of people whose money is at serious risk over there."

*****

On Oct. 21, 2008, at an event celebrating Triton's newly announced sponsorship deal with the PGA Champions Tour, money didn't seem to be a problem. Barton was called a "visionary" and a "leader" by none other than Texas governor Rick Perry, a Texas A&M grad who bantered about the 1990 Holiday Bowl with Ty Detmer, BYU's quarterback in that game, before praising the company's "more than $100 million in assets and revenues this year."

But just last month, the PGA Champions Tour took the Austin-based Triton Financial Classic off its 2010 schedule after only one year of existence. The company had failed to pay its 2009 sponsorship fee of $1.5 million. Triton still has two years remaining on its three-year sponsorship contract, at $2.5 million for 2010 and 2011.

Publicly, Triton blamed the economic climate. "What I hope is going to happen is that the event will continue here, because I think it's a great event," Barton said on Nov. 5, after the tournament was canceled. "But the economy's just tough."

Tom Alter, the Champions Tour's vice president for business affairs, could not be reached for comment yesterday. But Alter told SI.com on Monday, before the SEC had filed its complaint, that the PGA was "continuing to explore our options and hopes to get a return on our investment in that event."

On Monday, Rob Whalen, the director of the Heisman Trophy Trust, told SI.com that its partnership with Triton -- like that of its deals with ESPN, Wendy's and Nissan -- was still intact, and that one reason they had entered into such a partnership was Triton's employment of Heisman winners like Detmer and Weinke.

"There's a perception that if pro athletes invest with a certain company or promote it, that there's some kind of respectability to it," says Dallas-based financial adviser Ed Butowsky, a former senior vice president at Morgan Stanley who manages the portfolios of pro athletes and other high-net-worth individuals. "But it's often not the case. It can divert attention from the facts."

Another fact worth noting is Barton's own background. According to government documents filed by Triton on Oct. 29, Barton -- a former employee of Aragon Financial Services and a frequent guest "financial expert" on Austin's local TV station, KVUE -- lists his formal education as "B.S., Colorado State University, Science, 1991."

But Colorado State University's records office tells SI.com that Kurt Branham Barton, whose date of birth matches that of Kurt Branham Barton, CEO of Triton Financial, never actually graduated from the school, though he did attend from the fall of 1987 to the spring of 1991. (The records offices at CSU-Global, Colorado State's online school, also does not produce any record of a Kurt Barton; nor does that of CSU-Pueblo, the separate but similarly named institution.)

*****

On March 30, 2007, the year before Triton became a paid sponsor of the official Heisman Trophy Trust -- thus allowing their logo to be featured on the ESPN broadcast of the awards ceremony -- the firm decided to purchase a Dallas sports marketing company, The Sports Group, which had launched the Heisman Winners Association (HWA), an organization founded in 2002 to market the players who won the trophy themselves.

By year's end, the images and bios of former college stars such as Archie Griffin adorned 20-page pamphlets for Triton Financial and also appeared on the company's Web site, clearly labeled "TRITON INVESTOR." But Griffin, the only two-time Heisman winner, tells SI.com that he "was never an investor in Triton" and had to ask them to remove his photograph. (Triton did so.) The same went for former Ohio State star and Heisman Trophy winner Eddie George.

Mark Panko, who co-owned the Sports Group with Eric Lindberg, says they agreed to sell the company to Triton because of the "added resources they committed to help fund its growth and expansion." But after the two stayed on as vice presidents of the newly renamed Triton Sports Management, things allegedly turned sour. "In our business, trust means everything," Panko says. "We founded the HWA. We had a client relationship built on six years of trust. It was our job to protect their rights. When I began to see the violation of the various agreements and the liberties being taken with Heisman winners' rights, I had a problem."

Panko and Lindberg, who were ousted from the company in the spring of 2008, filed a breach of contract claim on July 14 of that year alleging that Triton failed to fulfill the terms of their purchase agreement (primarily concerning proposed financial compensation and the degree of control retained over the company). The case is set to go to trial on April 4, 2010.

Meanwhile, the HWA had its own objections with Triton stemming from unpaid funds, and on Aug. 1 of this year ultimately reached a settlement of $50,000 with the company that was to be paid by Aug. 20. But documents filed in Travis County court yesterday claim that the HWA was never paid by Triton and has now filed a motion to enforce that settlement.

A year before that, in August 2007, Triton also opened "Earl Campbell's Pro Player Auto" in Texas City, a car dealership that was supposed to be the first in a series of sports-themed dealerships statewide. It closed within a year and the plan fizzled out.

"It was a total flop," says Jack Pagan, a Texas businessman whose family has more than 50 years of experience in the automobile business. Pagan severed ties with Triton in the spring of 2008 after being hired to run Campbell's dealership. "They said they were going to do 100 dealerships, but that was just the kind of stuff they'd do to get everyone jazzed up. They had great ideas, but they never had the cash to back up those ideas. There was no way I could stay with them and save face anymore."

A message left on Campbell's cell phone earlier this week has not been returned.

Triton, though, continued to tout itself as a favored investment firm among football players. Detmer, Blake and Barton estimated to SI in March that the number of pro athletes who were Triton clients was 30, 70 and 100, respectively. But several former employees who requested anonymity due to ongoing legal proceedings say that the sports sponsorship deals and football players Triton employed most effectively served to boost the confidence of everyday, non-athlete investors.

In fact, at least according to a mailing list of Triton's current investors that was accidentally e-mailed out to clients by Barton on Oct. 30 (and obtained by SI), Triton manages a total of 335 separate accounts. But of those 335, only 12 appear to be current or former pro athletes (all from the NFL). And after Ty Detmer, Koy Detmer, Tony Dorsett and Chris Weinke are subtracted, only eight players -- the first four of whom are Philadelphia Eagles -- remain: quarterback Kevin Kolb, tight end Brent Celek, kicker David Akers, tight end Matt Schobel, defensive end Aaron Schobel, center Matt Birk, running back Earl Campbell (whose listed address, curiously, is Triton's office) and quarterback Brian St. Pierre. Several people who share the players' last names are also investors.

Messages left with those players this week have not yet been returned.

*****

One of those everyday, unsophisticated investors lured by such bold-faced names and faces was Christine Cayton.

Cayton, the wife of a pipe designer, had been reading self-help finance books by Robert T. Kiyosaki (namely Rich Dad, Poor Dad and Rich Dad's Prophecy: Why the Biggest Stock Market Crash in History Is Still Coming...andHow You Can Prepare Yourself and Profit from It!) and wanted to move her family's savings out of Wall Street into something tangible. And then she came into contact with Triton, which pushed a strategy of purchasing "alternative investments" like distressed real estate properties and insurance companies exclusively with cash. At Triton's offices, Heisman winners and NFL players roamed the halls.

"It was like meeting superstars or something," Cayton says of her first visits to Triton. "[Triton employees] asked me, 'Do you know what the Heisman Trophy is?' And I thought to myself, They've got millions. Why would they ever want to do something that would hurt their name or their reputation with my little dinky money?" Cayton says she had a cell phone photo taken with two quarterbacks, Ty Detmer and Jeff Blake, the day she agreed to invest all of her family's $125,000.

But after making the investment, Cayton alleges in her lawsuit, she stopped hearing from Triton. No updates. No dividend checks. After writing a series of letters to the company and repeatedly showing up at the offices herself, Cayton says she threatened to hire a lawyer and contact the Texas State Securities Board if she didn't get her money back. Cayton then says she was personally handed a partial refund check for $25,000 by Chris Weinke. According to one e-mail Cayton saved that was shown to SI.com, Kurt Barton later pledged to refund the rest by Dec. 4, at which point "mutual releases would be signed."

Dec. 4 came, but her money didn't. So she filed her lawsuit. And then -- after one more week of waiting -- she went back to Triton with a gun in tow.

On the Triton Financial Web site, memorably, there had once been a video interview with a grinning Ty Detmer, who, months after leaving the company, became a high school football coach in southwest Austin. The closing lines in his online Triton testimonial -- which has since been taken down -- were as follows:

"For us, it's more than a job. It's putting your reputation on the line that this is a solid company. And you know I wouldn't be involved if I didn't feel really good about it."