Moneyball opened our eyes, but it wasn't a game-changer

With the 2003 publishing of Michael Lewis' Moneyball, the baseball establishment was turned on its head. Lewis' book chronicled Oakland A's general manager Billy Beane and his organization's successful attempts to outwit teams with far more resources by using the power of advanced statistical analysis. By scooping up undervalued players on the cheap, Oakland was able to compete with the big-market clubs despite suffering major monetary disadvantages. The centerpiece of Beane's strategy, of course, was its emphasis on on-base percentage and drawing walks. Beane was willing to accumulate slower, poor-fielding, unimpressive looking players that other teams had discarded as long as they could get on base. Drawing walks wasn't pretty, but it won ball games, making Oakland one of the premier AL teams during the first decade of the 21st century.

But this was precisely what worried many traditionalist fans and commentators. After all, if every team started playing Moneyball, wouldn't the game essentially turn into a slow-pitch softball league, filled with nonathletic, one-dimensional fat guys who took pitch after pitch? While everybody loves to win, nobody loves walks. Watching 10-pitch at-bat after 10-pitch a-bat end without action isn't anybody's idea of a good time. Traditionalists wondered, if all teams adopted Beane's thinking, emphasizing patience and drawing walks, wouldn't the game's aesthetic appeal be ruined?

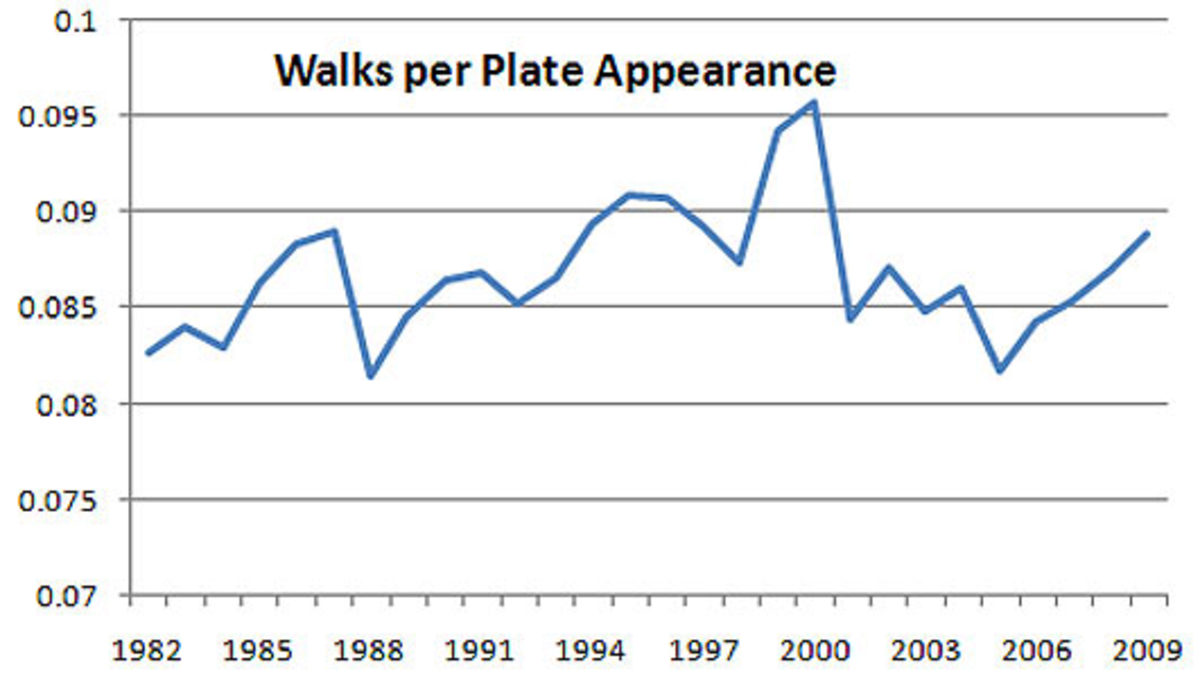

Eight years later, other teams have caught up with Beane's approach. Nearly every team in the majors has come around to see the value of drawing walks and on-base percentage. Mainstream media now routinely quote a player's OBP and OPS, and walks are no longer vastly underrated. So have the fears of a boring Moneyball-style league come to fruition? If teams were now coaching players to draw more walks, we would likely see a rising trend in the number of base on balls since the publication of Lewis' book. Do we?

In fact, the above chart of walks per plate appearance below doesn't support that line of thinking. While the amount of walks has fluctuated over the past 30 years, there's certainly no evidence that walks are overrunning the game. Walk rates peaked in 2000 -- three years before Moneyball hit the shelves. Last season, seven years after the book's debut, players walked no more than they did during parts of the mid-1980's, when nobody had ever heard of OPS and Bill James was just an egghead who couldn't know a thing about the game because he had never played it.

Skeptics will point out that the graph above shows that walks have risen slightly each year since 2005. Fair enough. Perhaps teams are just now catching on and the trend of increasing walks will continue into the future. Perhaps young players are being coached to be more patient, and walks will take over the game when these young players arrive in the big leagues. If this were true, we might see a vastly different game being played in the years to come. For some indication on how the future of the major leagues may look, let's take a look at what's going on in the lower levels of the minors. Are teams building vast armies of Kevin Youkilises and Jack Custs that will grind the fun out of the game by drawing walk after walk?

The above chart shows the number of walks per plate appearance in the Class A Midwest League and South Atlantic League. Far from an increase in plate discipline, there has been a steady decline in the amount of walks taken over the past 20 years at the minor league level. There's certainly no evidence that teams are programming their young players to be more patient and draw more walks. Far from taking over the game, walks are down among Class A teams and the rise of Moneyball, on-base percentage and sabermetrics seems to have had no effect on the habits of young players.

In short, baseball is in no danger of become a league full of unexciting guys who take pitch after pitch. Since the sabermetric revolution, there has been very little change in the walk rate. While teams now value the base on balls to its full extent and players who take walks can earn a lot more money than they used to, this hasn't significantly changed the makeup of major league players. As players such as Ichiro Suzuki, Juan Pierre and Cristian Guzman prove, there is still plenty of room in the game for high-batting-average, low-walk, speedsters. They'll just be earning a bit less money than they might have before.

Another element of the Moneyball approach was its disdain for the speed game. Oakland routinely ranked last in the American League in steals during the early 2000s, preferring instead the lumbering Jeremy Brown types, who were underrated and could get on base. This was cause for concern for some baseball purists, who wanted to see the speed element of the game remain. Stolen bases and daring base runners are exciting to be sure, and if the Moneyball approach squelched this aspect of baseball, it could take some enjoyment out of the game.

The graph below shows the number of stolen base attempts per plate appearance during the past 30 years. While stolen bases are not as ubiquitous as they were during the 1980s, since the book's release the number of attempts has remained flat. There has been no dropoff whatsoever in the number of stolen base attempts since the sabermetric revolution in the early 2000s. I love a daring speedster as much as the next guy, but the continued use of advanced statistics poses no threat to him. Jacoby Ellsbury of the sabermetrically-inclined Red Sox stole 70 bases last year, the second-highest total of any player this decade. Even the Oakland A's had a 40-steal player last year in Rajai Davis. Players with blazing speed are here to stay and, whether they are from Moneyball teams or not, they are going to get the green light. Stolen bases continue to be an integral part of the game and show no sign of decline. Though stealing is down from its peak in the 1980s, the fact remains that teams are stealing far more bases than they did from the 1920s through the 1960s, and with a 72% success rate, are doing so more efficiently than at any time in the game's history.

The feared side effects of advanced statistical analysis have never come to fruition and likely never will. Not only that, but several aspects of sabermetrics are beneficial to the game's aesthetic appeal. For one, Moneyball advocated a reduction in the number of sacrifice bunts. From a fan's point of view, it's hard to make a case that sacrifices are a thrilling part of the game. More likely, fans would rather see their heroes swing away, and that's what sabermetrics generally advocates. Even so, despite the change in thinking, the number of sacrifice bunts during the last decade has changed only slightly.

Another more recent aspect of the sabermetric movement that could potentially help the aesthetic appeal of the game is the renewed emphasis on defense. In Moneyball, Lewis portrayed Beane picking up poor defenders off the scrap heap as long as they could get on base. However, times have changed. With advanced defensive metrics such as Michael Lichtman's Ultimate Zone Rating and John Dewan's Plus/Minus system, defense, especially in the outfield, has been shown to be more important than most people previously realized. As many observers have pointed out, defense is the new on-base percentage, in that some defensive players are undervalued and can sometimes be available for far less than they are worth. The fact that advanced statistical analysis puts a premium on defense certainly fits a purist's ideal vision of the game. Better defense means more exciting plays and hence, sabermetrics is actually pushing baseball towards a more traditionalist, aesthetically pleasing game.

However, the reality is that, like the other sabermetric revelations, the actual effect on the game itself is minimal. Defensive butchers like Adam Dunn will still populate the game, they'll just be paid a bit less. Chances are, the fan in the stands won't notice the game being played very differently at all.

In all, the fact that teams are now using more sophisticated statistical analysis has a very small effect on the look and feel of the game. For fans uninterested in sabermetric ideas, all of that statistical inside baseball can remain, well, inside baseball. The types of players who play the game and the way they perform on the field has remained remarkably constant in the face of this new style of thinking. While teams may now better understand the true value of Franklin Gutierrez's defense in center field or the value of Kevin Youkilis' walks, good players continue to come in all shapes and sizes. The main difference is that rather than being undervalued, these players now earn money in proportion to the value they bring to their club.

Regardless of current statistical thinking, the variety of types of players that populate the major leagues has not and will not change significantly. The only difference is that the advanced numbers have been able to more accurately assess the value of each player. While that's useful, it's not going to affect the view from grandstand. Juiced balls, a changing strike zone, artificial turf, steroids and the height of the mound all changed the aesthetics of the game far more dramatically than subtle shifts in statistical analysis ever will. While Moneyball may have changed the landscape of the game inside front offices and in the media, traditionalists can breathe easy that the sabermetric revolution has not dramatically changed the on-field product, and likely never will.