Chargers' Kaeding explains lonely life of kicker, looks to rebound

Until second-year New Orleans kicker Garrett Hartley's dead-center, 40-yard, overtime missile won the NFC Championship Game last Sunday, kickers had been a storyline and a punch line this postseason. In 10 playoff games, kickers have made just 20 of 33 field goal attempts (60.6 percent). You have to go back 25 years to find a worse postseason performance.

The current playoff failure doesn't jibe with the regular season, when kickers made 81.3 percent of their field goal attempts, the fourth-best season ever. But it does jibe with history, and probability. Since 1984, NFL kickers have performed better in the playoffs than in the regular season 10 times, worse 11 times and about the same five times. Given the small sample size of kicks, a really bad postseason, with some prominent misses, was inevitable.

When a kicker fails in the playoffs, it's news. Scott Norwood will forever be known for his Super Bowl-losing miss for Buffalo in 1990. Mike Vanderjagt was run off by Indianapolis after missing a game-tying kick in 2005. Fair? It's human nature to define athletes by their most memorable successes or failures, so that's what fans and media do.

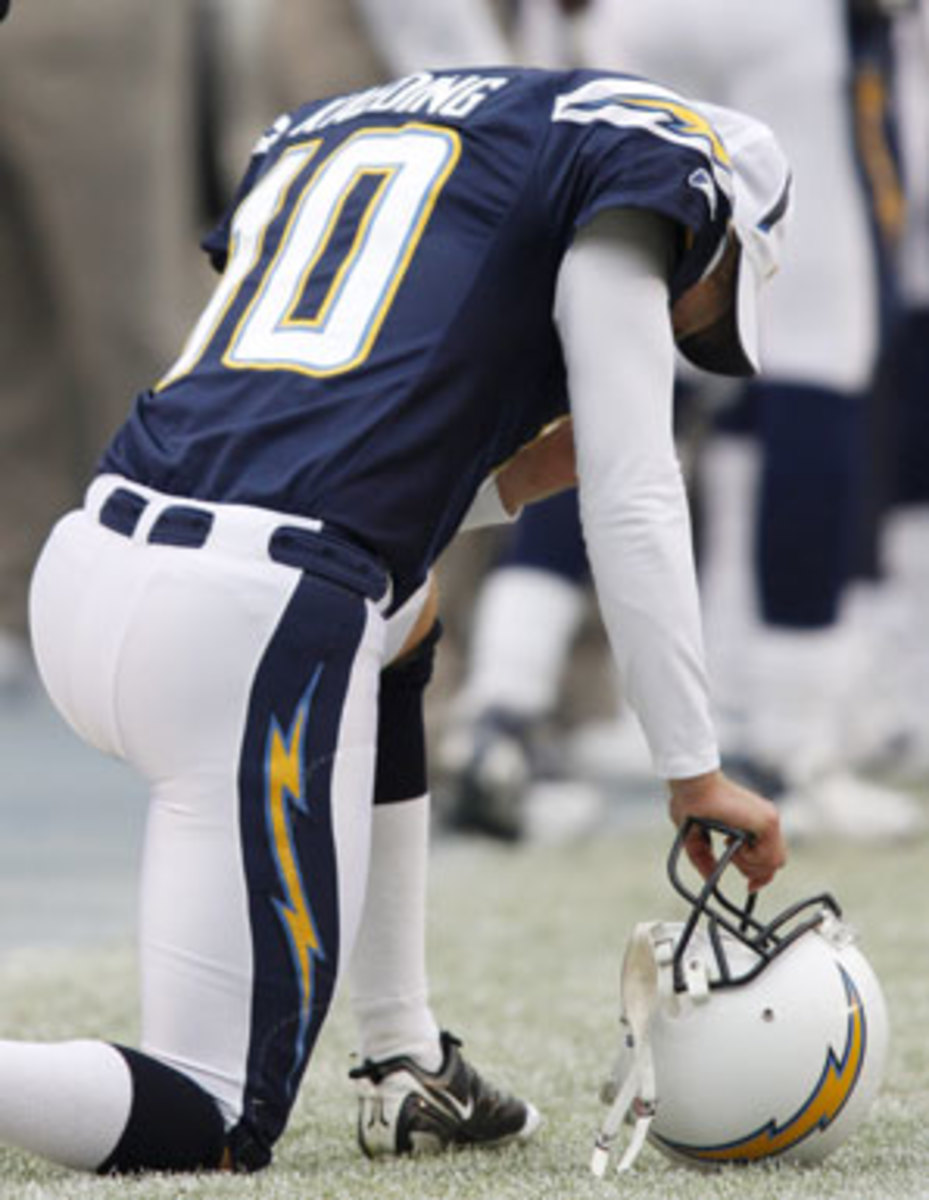

And that's what they are doing now to Nate Kaeding of the San Diego Chargers.

Full disclosure: I first talked to Kaeding last year for a piece in SI explaining why this is the golden age for placekicking. He said he had read my book about spending a training camp with the Denver Broncos as a kicker. After the season, he called to say he was on a board to promote his hometown Iowa City's designation as a UNESCO "City of Literature." He thought the city could host a Scrabble tournament, and wanted to learn more. (My previous book was about that game.) In the offseason, we had lunch in Washington, where Kaeding, a political science major at the University of Iowa, was tagging along with Iowa City officials visiting their congressional delegation. Kaeding is intelligent, friendly and thoughtful, and we've stayed in touch since.

After his 0-for-3 performance against the New York Jets in an AFC divisional playoff game, I sent a condolence e-mail and asked if he'd be willing to talk about what happened, and why. We spoke on Tuesday, after Kaeding arrived in Miami for Sunday's Pro Bowl. He had earned a spot in the game by making 32 of 35 regular-season field goals, increasing his career percentage to an NFL all-time best 87.2 percent. He also led the NFL in scoring with 146 points.

But in the media narrative, Kaeding had a reputation for playoff failure. As a rookie in 2004, he missed a 40-yarder in overtime against the Jets. In 2006, he missed a 54-yarder with three seconds left to tie New England. In 2007, he missed a 45-yarder against Tennessee and a 48-yarder against the Colts. But since then, he had made six playoff kicks in a row: four in the 2007 AFC Championship Game, a 21-12 loss to the Patriots, and two in 2008.

Entering the Jets game, Kaeding didn't give his playoff reputation a thought, because in his mind he didn't have a playoff reputation: The misses were a lifetime ago. After a career-best season, he even was feeling even less than the usual pregame jitters. "I just felt pretty damn good and ready to play," he said. "No nerves whatsoever.''

And then, boom. In the first quarter of a scoreless game, Kaeding missed from 36 yards. It was his first miss after 20 makes and his first miss from inside 40 yards after an NFL-record 69 makes. "I just got blindsided," he said. "It was going so good for so long it was like the world came crashing down on me with that miss. It was so far out of my belief of what would happen in that game."

When he was called on to kick again, Kaeding couldn't suppress those feelings. He missed a 57-yarder before halftime that landed short and right, and a crucial 40-yarder late in the game that went wide right. The mental lapses surprised him. Kaeding is proud of his ability to rebound; he wouldn't have made it this far if he couldn't.

"I learned long ago that the biggest room for improvement I have is in your mind," he said. "That's your biggest obstacle at this point. You're strong and healthy as ever, you're technically refined. Now it's just a matter of handling the variety of mental and emotional situations you're thrown as a kicker.

"There was a situation thrown at me I wasn't prepared to handle. That's tough to admit as an athlete, as a person. I wasn't tough enough to handle it on that particular day. There's no doubt in my mind I could step out there and kick a game-winner in the Super Bowl, no doubt in my mind I could make it.

"I've got some room to improve . I'm not afraid to admit that. This is the reality of my current situation. I'm not one to run and hide from it."

That sort of candor is unusual in an athlete, and refreshing. It may not make fans feel any better about "their" team's big defeat, but it should help them understand sports and athletes better. Failure happens. It'll happen again. Michael Jordan famously said he missed 9,000 shots in his career, 26 with a game on the line. It's not easy to determine why athletes fail. But they try to, because their livelihoods depend on it, because it makes them better.

So what did actually happen to Kaeding, psychologically? Why did he fail? I asked David McDuff, a psychiatrist for the Baltimore Ravens who worked for years with Matt Stover, who will be kicking in the Super Bowl for the Colts, for his take. Kicking involves a highly concentrated form of pressure, McDuff said. The time between the beginning of the act and the result "is as compressed in sports as you get. It's almost like someone puts a cylinder of pressure around the person and just cranks it up."

Missing a kick in a big game results in "an exponential increase in the pressure," McDuff said. "Each miss makes you think more about the importance of the misses. It's not three misses. To me it's nine misses."

Many athletes use physical cues to help override mental distractions. For instance, Stover's need to focus on his bent-over, King Tut stance may help shut out mental noise. In his autobiography Open, Andre Agassi writes that he tried to balance caring and not caring. Caring too much can mean obsessing about the situation or the pressure. Not caring enough can mean failing to pay enough attention to the technical aspects of the physical act. On that Sunday, on those kicks, Kaeding cared too much.

After the game, Kaeding went home with his wife, Samantha, and two boys, 20 months and five months old. He couldn't sleep. He returned to the Chargers' facility at 5 a.m., boxed up his gear and had his end-of-season physical. He received dozens of calls and e-mails and texts from friends, "who know more about me than balls going through the posts." Teammates and coaches, including Chargers coach Norv Turner, were supportive. Kickers as good as Kaeding earn respect. And professionals know that failure happens -- and that Kaeding alone certainly didn't cost the Chargers that game.

"The whole team wasn't playing well," said David Binn, the Chargers' long snapper. "If you're a player or a coach or you know football, there was stuff everywhere. The average fan doesn't know that. Most of the media don't, either. The kicker's the easy one to point at.''

Kaeding didn't watch television or read the papers for a couple of days. Chargers fans were predictably, brutally cruel. When Kaeding did turn on the TV, a promo for the local news showed the Haiti earthquake and then cut to a Chargers fan at a Wal-Mart attempting to get a refund on a Kaeding jersey.

"I wasn't really angry, but it framed it for me," Nate said. "That's the privilege and right fans have. They have the right to buy into what I'm doing when it's going good and sell when it's going bad. I don't have that right. My name's going to be attached to me whether I do good or bad. That was my name on that Sunday in that playoff game. But I have ownership over what I do. It's a reminder of the challenge that lies ahead: More and more of the outside noise coming from people who have that right to give up on you and on any athlete.

"But I'm in this regardless of the good times or bad. You're a kicker. There are going to be down times. Some are going to be extreme like this. You can't just jump out of it when you feel like it."

Kaeding wasn't looking forward to getting on a plane to Miami for the Pro Bowl. But Turner and, eventually, Kaeding agreed that kicking again would help speed his recovery process. ("A. Coming to terms with what happened. B. Deciphering why it happened. C. Formulating an actionable solution/plan to ensure that it doesn't happen again," Kaeding e-mailed me after we spoke.) The Chargers staff was working the game, and Kaeding was friends with the AFC's Pro Bowl punter, Shane Lechler of Oakland. That would help.

On Wednesday, Kaeding kicked a dozen or so balls with Lechler holding. On the next one, he cocked his foot back and felt something strange. An MRI revealed a hamstring injury. He went home to Iowa City on Thursday and will have another MRI to determine the extent of the injury and then begin treatment.

Kaeding explained the news without self-pity. Only resignation and a little disbelief. The Pro Bowl, he said, "was just a good way to kick a few balls and start moving the train forward." The train stopped, and another passenger got on. "It's mystifying for me," he said on Friday morning. "But these things, like life, you can't really know or control. Things just happen."