After enduring years of ankle problems, Hill's time is now

This story appeared in the May 24 issue of the magazine.

Grant Hill lay in a hospital bed at the Duke Medical Center in the spring of 2003, Kobe Bryant on his television and James Nunley in his ear. Nunley, the chief of orthopedic surgery at Duke, was reminding Hill of all the postretirement options that awaited a magnetic basketball star with a spotless reputation and a gift for public speaking who was educated in art and medicine, connected in media and real estate, at ease in front of politicians and the pope. "I thought he could be president," Nunley says. But Hill's attention kept drifting to the TV, on which Bryant was savaging one foil after another on the way to his third consecutive NBA championship.

Hill was coming off his fifth left-ankle surgery in four years and a staph infection that nearly killed him. He was staring at another long rehab, another lost season. He could not have kept up with Bryant in a sack race, much less a playoff series. His team, the Magic, was trying to buy out his contract. It should have been time for him to listen to Nunley and think about a second career, but the White House would have to wait. Hill still believed he could get to where Bryant was.

Today Hill does not tape the ankle and does not protect it with a brace, and on summer days he does not even cover it with a sock. He appreciates when people do not mention it, because he is no longer Grant Hill with the bad ankle but simply Grant Hill with the Phoenix Suns, and he has been for some time. But when he talks about those days in the hospital at Duke, the beginning of a comeback that is finally nearing its climax, he reflexively looks down and to the left, to the part of his body that once infuriated him and now delights him. He has a pleasant expression on his face, a bemused half-smile, as if he is gazing upon a child who has made him both nuts and proud. The ankle stole his youth, plundered his prime and probably wiped away his spot in the Hall of Fame. And yet, in a twist that only someone as optimistic as Hill could have foreseen, the ankle has also given him the second career he yearned for.

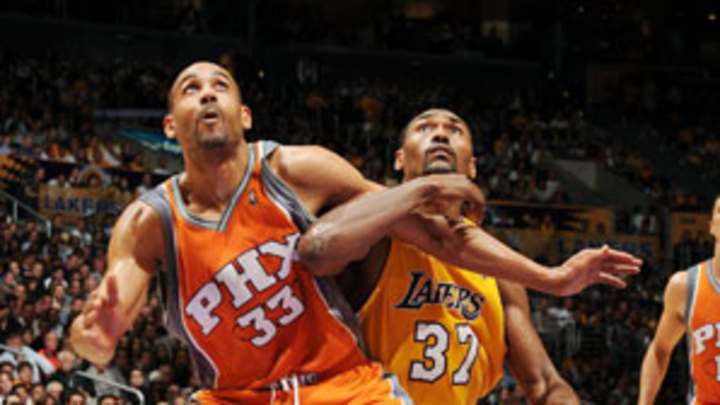

Defense is about determination, guile and, most of all, moving your feet. The ankles, like hinges, control how the feet move. When a defender is caught in the wake of a nasty crossover dribble, players say he had his ankles broken. If he has his ankles broken enough, the only thing he'll be trusted to guard is the Gatorade bucket. But here is Hill, on ankles that have literally been broken and rebroken, assigned to shut down one of the great ankle breakers of all time. Seven years after Hill watched Bryant from his hospital bed, he is shadowing him in the Western Conference finals.

Hill likes to say he is back in the Final Four, a nod to his days at Duke, when he was a regular there. To those over 25, Hill is the consummate winner, a two-time national champion, co--Rookie of the Year with the Pistons in 1995, twice the leading All-Star vote getter, once a third-place MVP finisher behind Karl Malone and Michael Jordan. But many of today's players, who were toddlers when Hill made the heave to Christian Laettner, do not remember all that. "I know he wore Filas, was the second coming of Jordan and couldn't get out of the first round of the playoffs," says Suns guard Jared Dudley, who was six when Laettner's last-second turnaround beat Kentucky in 1992.

Last month Hill, who entered the season winless in six playoff series, was in danger of another premature exit, as Portland's Andre Miller piled up 31 points in Game 1 of the first round to upset the Suns at home. The next day Hill went to coach Alvin Gentry and asked to take Miller. He used to do the same thing in Detroit, begging for a turn on Jordan, but the Pistons needed his 25 points per game, so they refused. In Phoenix, Hill is only the fourth-leading scorer on the team, so Gentry obliged. Miller shot 35 percent for the rest of the series, including 2 for 10 in Game 6, when the Suns clinched. In the next series, against San Antonio, Hill held Manu Ginóbili to 41 percent shooting, and 2 of 11 in Game 4, as the Suns swept. A 37-year-old stopper was born. "He's our Michael Cooper," says Suns general manager Steve Kerr. While some former MVP candidates might bristle at being compared with a career 8.9-point scorer, Hill would be flattered by it.

At Duke he saw Laettner lead by verbal intimidation. Hill leads by quiet example, diving after every loose ball, forcing younger teammates to think, If that old guy can do it, I should too. Until recently the Suns' definition of defense was a quick inbounds pass after giving up a basket. But Hill has goaded them into moving their feet. He is so enamored of this team that he second-guesses himself for not having pursued a book deal last summer to write what he envisioned would be a contemporary version of Bill Bradley's Life on the Run about this season.

After the Suns returned victorious from San Antonio on the morning of May 10, Hill and his wife of 10 years, Tamia, drove home from Sky Harbor Airport. "Can you believe this?" he asked.

"You've come full circle," she said. "Think of what it took to get here."

Hill has been relatively healthy for four years, and the details of his rigorous physical rehabilitation are well chronicled. But there were also psychological obstacles because each time Hill retraced the origins of his ordeal, he became more frustrated.

The first operation was performed in April 2000, when Hill was still playing for the Pistons, by an independent surgeon named John Bergfeld at the Cleveland Clinic. When Hill was traded to the Magic in the first week of August, Bergfeld forwarded the instructions for Hill's rehab to Orlando, where his friend James Barnett was the team's head physician. "You'll be in good hands," Bergfeld said.

Then, in September, Barnett and his wife Missy flew their twin-engine plane to Mississippi. The plan was to visit relatives in Brookhaven and then continue to an Ole Miss football game. The plane went down in a grassy field near the landing strip in Brookhaven and both passengers were killed. Hill arrived in Orlando with a $93 million contract, a mandate to deliver a title, and a medical staff in mourning and in flux. "The lines of communication got crossed," Hill says.

Starting in training camp, the Magic wanted to see what Hill could do. Hill wanted to show them. "There was a shared excitement for him to play," says then Magic general manager John Gabriel, now the Knicks director of scouting. But Hill knew his ankle was still ailing. "I was limping. I was in pain," he says. "It got to the point where people were telling me to play through it. I was shocked at how casual they were. I started questioning myself like, 'Maybe this isn't a big deal, maybe it's just scar tissue.'"

Gabriel disputes the notion that Hill was encouraged to play through pain, "I don't think anybody one way or another could take the blame," he says , and a person familiar with the situation said Gabriel told trainers and coaches that Hill's long-term health was to be the priority.

So Hill played in training camp and the preseason -- until he found out from Bergfeld that he hadn't wanted Hill to play until late November or early December. Soon after, a CT scan revealed a nonunion in the ankle, which meant that two parts of the bone had healed but not healed together. It took three years to fix. "We thought it was a stress-reaction fracture, and he would heal like anybody else and come back," Gabriel says.

The Magic was not alone in its bewilderment. Three years in a row the NBA, presuming Hill was on the verge of a return, denied Orlando an injury exception, which would have allowed the Magic to sign a replacement for Hill. Gabriel called and visited dozens of foot and ankle specialists. "Everyone had a different opinion," he says.

Hill says he deferred to the Magic's choice of surgeon so that "the lines of communication [between doctor and team] would be better than the first time." The team picked Mark Myerson, the president of the American Orthopedic Foot and Ankle Society, to perform Hill's second and third operations, in Baltimore. "After the third one, Dr. Myerson told me that nothing else could be done," Hill says. "So I went back to Duke."

Nunley alleviated pressure on the ankle by removing a wedge of bone from the heel. He ordered Hill to sit out the following season and gave him a piece of news that infused him with hope. Despite everything the ankle had endured, the joints and ligaments were still strong. The only problem was the bone. Once that heals, Hill told himself, I'll have fewer miles on my body than other guys my age. I'm going to be able to make this up on the back end.

As counterintuitive as it sounds, the injuries kept Hill young. If he had not been quarantined for so long, he might not be able to guard the game's best player now. Gentry's daughter has the perfect nickname for him: Benjamin Button.

For those who like their playoff series served up as morality plays, Bryant and Hill form an intriguing matchup: one of the most polarizing figures in sports against one of the most beloved. Kerr still wishes Hill had married his daughter. Gentry compares him to President Obama. This season, after Hill won the NBA Sportsmanship Award for a record third time, Nunley called him and said, "There's no one in the world like you."

Hill has been famous for more than two decades and never generated a whiff of controversy. Growing up in Washington, D.C., he remembers the scandals involving presidential candidate Gary Hart and D.C. mayor Marion Barry, and his mother, Janet Hill, warning him, "Don't fear failure. Success ruins more people."

But even Hill, preternaturally cool, needed time to assuage the bitterness that built up in him in Orlando. "It was hard for me to go to work there every day and be around people who I felt failed me," he says. "Even now, that arena has a lot of dark memories for me." He pauses for a moment, remembering that he might be stepping back into that arena in a couple of weeks for the NBA Finals. "I might have to get over that pretty soon," he says.

Hill arrived in Phoenix three years ago, for the cut rate of $1.9 million per season, and the day he signed his contract he went through a 2½-hour physical assessment with the Suns' renowned medical staff. On the drive back to his hotel he nearly broke down at the wheel, overwhelmed by the care he finally felt he was getting. Last summer Hill had a chance to sign with the Knicks for more money and the Celtics for what seemed like a better chance at a championship, but he re-upped with the Suns in part for their trainers.

Hill has hired a macrobiotic chef, sees an acupuncturist and has bought into the Suns' innovative corrective-exercise program, in which every player is assessed daily and given exercises to address physical imbalances. Last season Hill played all 82 games for the first time. This season he played 81. Others can hog the points and rebounds; to Hill, minutes are the metric that matters most. Each is an unexpected gift.

He prefers to reflect on what the ankle gave him rather than what it took away. It gave him a more thorough knowledge of medicine and the mechanics of movement. It gave him a basis from which to counsel young players such as Jameer Nelson of the Magic and Shaun Livingston of the Wizards through injuries. It put to rest the myth of his perfect life. "It may have been bad for my career," Hill says, "but it was good for my development as a human being. In a weird way I'm glad it happened."

When Hill went to Phoenix, he expected to be retiring around 2010. Instead he has reinvented himself as a player and won a long-awaited turn in the spotlight. He can see himself playing another three years. Political office, which Obama suggested he consider after Hill introduced him at a fund-raiser, can wait. Kobe Bryant cannot.

This is the ultimate challenge in a career defined by them. Hill has seen Bryant enough to know what's coming: the killer crossover, the clever up-and-under, the maddening fadeaway just over everybody's fingertips. "The key is not getting discouraged," Hill says. "You can't ever get discouraged."

That happens to be his forte.