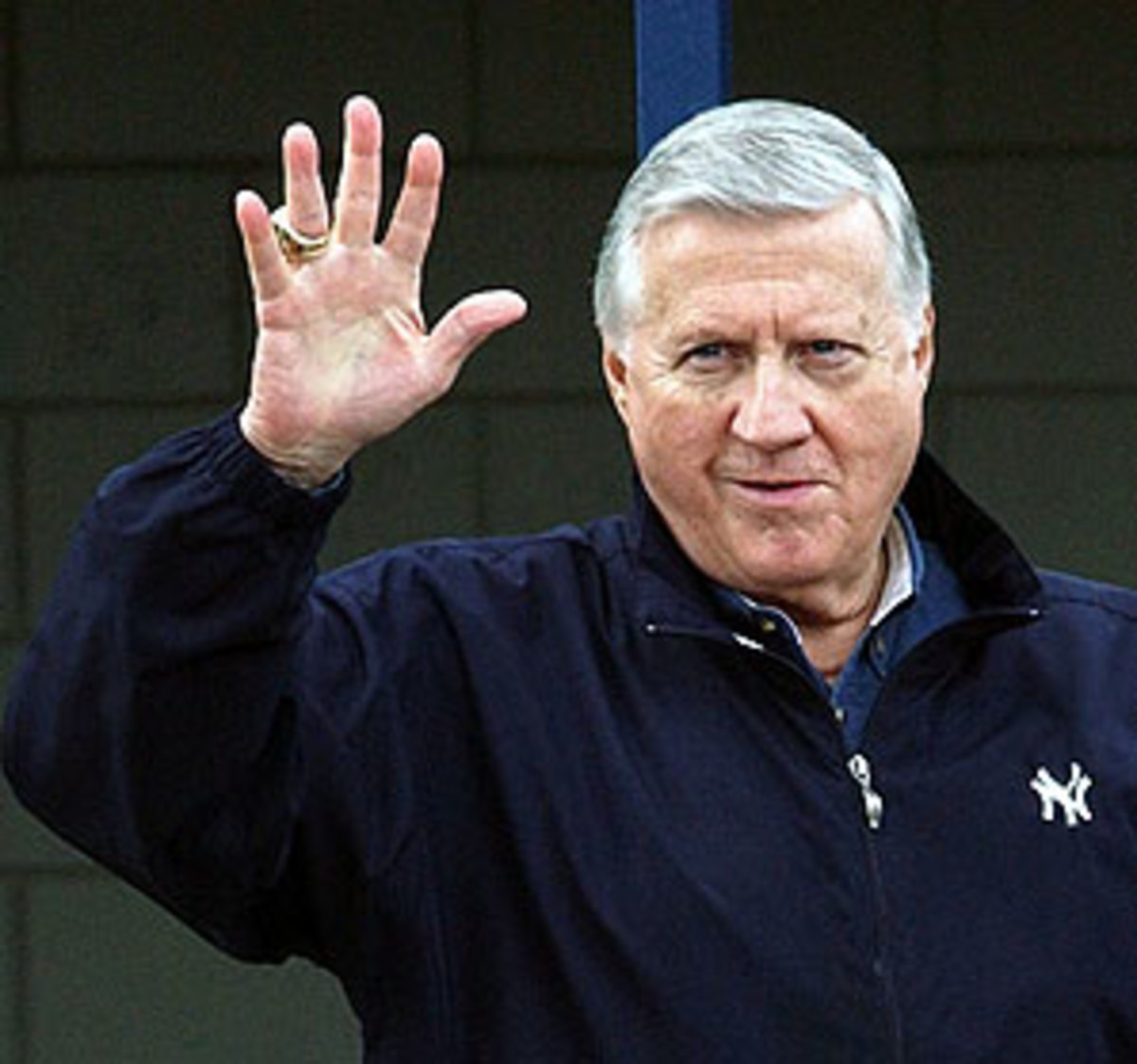

As Yankees owner, Steinbrenner was a bridge to baseball's future

With the death of George Steinbrenner, we will undoubtedly hear endless stories about the imperious nature of the man who called himself The Boss. He was in the words of one writer, "every worker's nightmare, the satanic CEO, a fanatically controlling overlord who borrows his warmed-over rhetoric from Vince Lombardi and his managerial style from Stalin." One of Steinbrenner's favorite lines was, "I don't get heart attacks. I give them."

There was another side to this bombastic man as well: a side that even his detractors acknowledge was always there. When I was 11 years old, the legendary columnist from the New York Daily News and later the Post, Dick Young passed away. Young wore his prejudices on his sleeve, and wrote in a pugnacious style that made you gnash your teeth.

It was announced in the morning paper that the service would be open to the public. I couldn't help but notice that the Manhattan-based funeral home was a mere 10-minute bus ride from my house. Like any normal 12-year-old in New York City, I dressed up in a blue blazer and tie and went to Young's funeral. Everyone from the New York sports scene was present, from St. John's basketball coach Lou Carnesecca to the local sports anchors, perhaps straight from the television stations, the pancake makeup still streaked on their cheeks. I was out of my element. Also for an open service, there were no fans there that I saw, and certainly no unaccompanied minors, both of which made people's stares feel like daggers and the room's soft recessed lighting feel like a spotlight.

As I shuffled my feet, feeling more like a voyeur than a mourner, unsure whether I should make a break for the exit, a meaty hand clamped on my shoulder and started to rub the back of the head. "This guy's here. Now we can get started," he said as he guided me inside. I looked up and it was George Steinbrenner. He then pushed me inside roughly and turned his back to me, resuming his conversation with a big smile and a laugh. Several people then asked me, "Who are you?" I was more than grateful. Steinbrenner was doing what he told sportswriter Ira Berkow he loved most: "Inflicting some joy." As the late sports writer Dick Schaap noted, "that is a rather bizarre phrase: to inflict joy." But that day, upon me, he inflicted a little bit of mercy, if not joy.

It's remarkable how seamlessly this story fits with the Steinbrenner people remember: the kind of guy who would reach out to an awkward kid like some kind of Daddy Warbucks, and then shove him inside. He was a part of that last group of the paternalistic owners, the people who felt like it was their duty in ownership to plow profits back into the team, creating a brand that could change the way a city saw itself.

But before we wax nostalgic, we should remember that Steinbrenner, while being a bridge to the past with his larger than life personality, was also a bridge to the future. This was the kind of man who was the model for owners from coast to coast on how to hold cities hostage for an endless flow of municipal funds. He was the kind of man who demanded costly stadium renovations in the 1970s, when the city was already enduring a fiscal nightmare. He claimed that he needed just $48 million to bring the stadium up to code. It ended up, according to Baseball Statistics, costing $160 million. He periodically threatened to move the Bronx Bombers to New Jersey, Connecticut, and most jarringly, next to Manhattan's West Side highway. He hired a 21-year-old clubhouse gofer with gambling debts by the name of Howie Spira and paid him $40,000 to dig up dirt on Yankees star slugger Dave Winfield.

Steinbrenner justified all his misdeeds by saying, "The reason baseball has its problems is that owners weren't involved 20 years ago. ... I'm an involved owner. I'm like Archie Bunker. I get mad as hell when we blow one." But Archie Bunker never was known as anyone's Boss. He never fired secretaries by the carload. He felt tossed around by a world changing too fast, in his mind, for its own good. George Steinbrenner created that world. Now, we live with the results.

If anyone ever seemed too big for New York, for better and certainly for worse, it was this man. They will say that his death signals the end of an era. But his life signaled the beginning of one.