Prep icon Hurley impacts countless lives with his old-school mentality

SPRINGFIELD, Mass. -- Some 30 hours before he was formally inducted into the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame (which should've happened a couple of years ago by the way), 63-year-old Bob Hurley Sr. was doing what he was born to do and which he has done with as much success as almost anyone -- preside over chaos. Kids were running this way and that, basketballs were flying off backboards and walls, and Hurley himself lent a note of informality to the proceedings by walking around holding in his arms his sixth and youngest grandchild, Gabriel.

"I always figured that if you can control this mayhem, anything else you do will be easy," said Hurley, shortly after ending a two-hour clinic for Springfield's youth at the Dunbar Community Center. "Organizing your clothes closet, going to the mall with your wife ... you know, all those other things that are not entirely pleasurable."

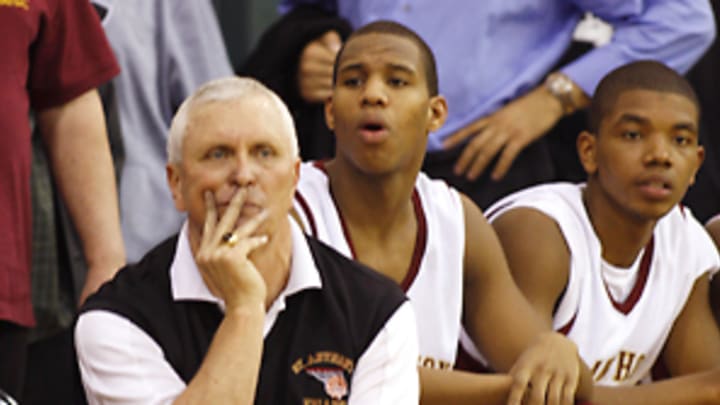

Hurley was smiling. Because for four decades this is exactly how he's gotten his pleasure. He is closing in on the absurd total of 1,000 wins at St. Anthony's High School in his native Jersey City (he has 984), but the foundation of his success has been at clinics like this, doing the dirty, underappreciated work, far from cameras and reporters, his Joisy voice cutting through the mud of limited attention spans, just one man trying to make a difference in kids' lives. The event was staged by Reebok, but it had none of the glamour and gloss often associated with youth basketball. Thank goodness for that.

"What happened here today is that a hundred kids got a T-shirt and a ball, they ran around a little bit, blew off some steam, and -- who knows? -- maybe one of them, maybe more, will get inspired to do something with their life," Hurley said. "It's a lot better way to do things than throwing money at an AAU team or giving money to a street agent."

He pauses amid the din in the crowded gymnasium.

"See, these kids don't know me, so there's a built-in lack of control," Hurley said. "At home, they know if Coach Hurley blows the whistle we all better be quiet. But here ... they don't know what a manic I am."

Maniac is on the outside edge of what Hurley becomes during the basketball season. But not far outside. In his outstanding best-selling book, The Miracle of St. Anthony's, Adrian Wojnarowski spent a season (2003-04) with Hurley and his high school team and chronicled the tale of a man who operates, from dawn to dusk, at the absolute upper edges of intensity. Hurley's zero-tolerance standards and the, well, spicy vocabulary he uses to make sure those standards are understood, were an eye-opening part of Miracle. But Wojnarowski was also able to demonstrate that it requires a 24-hour commitment to not only keep inner-city kids at an inner-city school out of trouble and not only keep them competing at the highest level of scholastic basketball, but also to direct them to college. More than 100 of his grads have earned Division I scholarships, an extraordinary achievement. And while it might be stretching a point to say that most of them would've been lost without this stern, stocky guy with the piercing blue eyes and the foghorn voice, it's not stretching it too far.

Hurley says that reaction to the book was relatively tame, given the glimpse it gave into a world that even basketball people don't see much -- the private lives of young men at a formative age and the tensions that exist among them and the father (and mother) figures who are trying to guide them. "What it did was show people what it was like to play at St. Anthony's," Hurley said. "So if you decide to come to the school you know what you're getting into. If you don't like what's going on, well, take your child and go elsewhere."

Given the race to the top that most basketball coaches engage in, it's astounding that Hurley has never gone elsewhere. In the 1970s, when he was a young coach, he interviewed at Yale and might've considered an offer as an assistant, but it didn't come. In the 1980s, he all but accepted a job as Pete Gillen's assistant at Xavier until he was, in his words, "assaulted by my sons" when he and his wife, Chris, arrived home from the visit to Cincinnati.

"I mean, they brought everything to it," said Hurley, smiling at the memory. "'Dad, we're in our formative years. Dad, how could you have us move when we're at this crucial age? Dad, you're never going to be home because you'll be out recruiting. Dad, we want to play for you at our school.'

"All in all," Hurley said, "it was a rout. I called Pete on Monday and told him I was staying."

Those sons, of course, are Bobby and Danny, both of whom played for their father, the former going on to fame at Duke, the latter to Seton Hall. Bobby had the bigger rep but it's Danny who's in charge now, having taken over the program at Wagner and hired Bobby as his assistant.

As Hurley's teams kept winning state championships (he now has 24), he no doubt could've gotten the Rutgers job or the Seton Hall job or any one of a dozen others. But at that stage in his life it was about something else. "In the early 90s, I wanted to watch Bobby and Danny play ball in college," Hurley said. "It was a great time for me, coaching my team and watching my sons play. Then we hit the late 90s, and I'm getting older. We're starting to get real mileage on the vehicle. So I didn't want to move. And now? I'm 63. You shouldn't want me now."

That's not true, for Hurley could still go in and turn around a program. He has always managed to change with the times. Early in his career he was influenced by John Wooden and Bob Knight (what young coach wasn't?), and Wooden's you-play-like-you-practice fundamentals still dominate his daily basketball life. Yes, his teams play, predictably, rigorous and relentless man-to-man defense. But Hurley never got into this we-play-my-way-and-that's-it mentality on offense. He ran Vince Walberg's dribble-drive that helped make John Calipari successful. (Walberg is an assistant at the University of Massachusetts, one of those guys who is well-known within the game but not outside of it.) This past season Hurley did a lot with the double-post offense popularized by Bill Self. And this year, he says, he'll be including some of the "cut and fill" offense that Bob Huggins runs at West Virginia.

"I think it's very important for an older coach that your players don't see you doing the same stuff," Hurley said. "You don't want to play for the coach who's over there diagramming a play and saying, 'You know, we ran this in 1961 and it worked really well.' Kids don't know from 1961."

At the end of the day, though, there's a lot of 1961 in what Hurley does. The emphasis on fundamentals. The reliance on strict standards. The idea that one person with a whistle can make a profound difference in the lives of kids if he or she is steadfast.

"In a lot of places high school coaches have lost their influence, to AAU coaches, to other people," Wojnarowski said. "But not at St. Anthony's. Bob told me once, 'You know, there's two or three of me in every state.' I don't know about that, but he does exemplify the old-fashioned guy who drove the bus, taped the ankles, swept the floor before practice. The great thing about Bob getting into the Hall of Fame is that it validates the idea of being a high school coach."

For Bob Hurley, being a high school coach was always enough. He loves his home in Jersey City, looking over the water at Manhattan, and he loves that Chris is still the biggest fan of St. Anthony's basketball. He loves that his grandchildren live close to him. He loves that Danny and Bobby will now be working together at Wagner, Danny exacting what the father called "the middle child revenge and sending Bobby out on the road." He loves the fact that, on Sunday morning, hours after he shares the Hall of Fame stage with immortals like Oscar Robertson, Jerry West, Michael Jordan, Magic Johnson and Larry Bird, he'll be climbing into his car and driving to the Poconos for a noisy basketball clinic.

And deep down inside, Bob Hurley still loves the fact that, in a few months, he will once again turn into a maniac. That's just the way it should be.

Special Contributor, Sports Illustrated As a member of the Basketball Hall of Fame, it seems obvious what Jack McCallum would choose as his favorite sport to cover. "You would think it would be pro basketball," says McCallum, a Sports Illustrated special contributor, "but it would be anything where I'm the only reporter there because all the stuff you gather is your own." For three decades McCallum's rollicking prose has entertained SI readers. He joined Sports Illustrated in 1981 and famously chronicled the Celtics-Lakers battles of 1980s. McCallum returned to the NBA beat for the 2001-02 season, having covered the league for eight years in the Bird-Magic heydays. He has edited the weekly Scorecard section of the magazine, written frequently for the Swimsuit Issue and commemorative division and is currently a contributor to SI.com. McCallum cited a series of pieces about a 1989 summer vacation he took with his family as his most memorable SI assignment. "A paid summer va-kay? Of course it's my favorite," says McCallum. In 2008, McCallum profiled Special Olympics founder Eunice Shriver, winner of SI's first Sportsman of the Year Legacy Award. McCallum has written 10 books, including Dream Team, which spent six seeks on the New York Times best-seller list in 2012, and his 2007 novel, Foul Lines, about pro basketball (with SI colleague Jon Wertheim). His book about his experience with cancer, The Prostate Monologues, came out in September 2013, and his 2007 book, Seven Seconds or Less: My Season on the Bench with the Runnin' and Gunnin' Phoenix Suns, was a best-selling behind-the-scenes account of the Suns' 2005-06 season. He has also written scripts for various SI Sportsman of the Year shows, "pontificated on so many TV shows about pro hoops that I have my own IMDB entry," and teaches college journalism. In September 2005, McCallum was presented with the Curt Gowdy Award, given annually by the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame for outstanding basketball writing. McCallum was previously awarded the National Women Sports Foundation Media Award. Before Sports Illustrated, McCallum worked at four newspapers, including the Baltimore News-American, where he covered the Baltimore Colts in 1980. He received a B.A. in English from Muhlenberg College in Allentown, Pa. and holds an M.A. in English Literature from Lehigh University. He and his wife, Donna, reside in Bethlehem, Pa., and have two adult sons, Jamie and Chris.