Tenth Inning lacks artistic punch of original but is still a joy

When Ken Burns was making Baseball, his epic PBS series, he once said that his ideal viewer was a middle-aged European woman. Burns knew baseball fans would watch, whether they liked it or not, but he wanted to go beyond that. He wanted to tell America's story through the institution of baseball and for a general audience. The series was a grand and loving tribute to the game but it was also about community and triumph, about hope and loss.

So Burns' audience is the casual fan, not just the fanatic, but at close to 20 hours, Baseball was an orgy for baseball lovers. And what fun would sports be if there wasn't something to argue about? Critics and viewers received the series favorably, but the sports media was often suspect. Veteran Philadelphia columnist Bill Conlin called it "Long with the Wind." On talk radio in New York, Mike and the Mad Dog played Monday morning moviemaker after each episode, harping on errors and pointing out omissions. But nobody was more critical than Keith Olbermann, who amassed a list of mistakes, 160 strong. "Can they suspend your poetic license?" asked Olbermann.

In making The Tenth Inning, a two-part, four-hour follow-up to Baseball covering the last twenty years, Burns' considerable savvy is on display right away: None other than Olbermann himself is the first talking head featured in the new series. Burns might have bristled at Olbermann's critique but he was shrewd enough to enlist his former antagonist this time around.

RELATED: Burns opens up about his new film

Burns is a filmmaker who has long surrounded himself with the best and the brightest, and here he shares writing credit with David McMahon and co-writing and-directing credit with longtime producer Lynn Novick. The film also lists a dozen Program Advisors including Geoffrey C. Ward, John Thorn, Kevin Baker, Howard Bryant and SI's Tom Verducci. One of Burns' great strengths is that rather than insisting on an auteur's singular vision, he seeks input from a braintrust that possesses more collective knowledge of the subject than he could possibly acquire on his own.

The good news is that we're in his capable hands once again and there is plenty to like about The Tenth Inning. The bad news is that the filmmaking isn't up to Burns' usual lofty standards. It won't spoil the experience, but it doesn't feel elevated. Still, Burns creates some fine moments, like the scenes in the Dominican Republic, the most beautiful in the whole show. Burns still has a gimlet eye (the one highlight of Robbie Alomar is right one). There is a small, shirtless boy at the end of "The Star Spangled Banner" in the first segment that is classic Burns. "The Bottom of the Tenth" begins and ends with a montage of Boston sports talk radio over original photography of an empty Fenway Park. It's a masterly touch, perfectly executed.

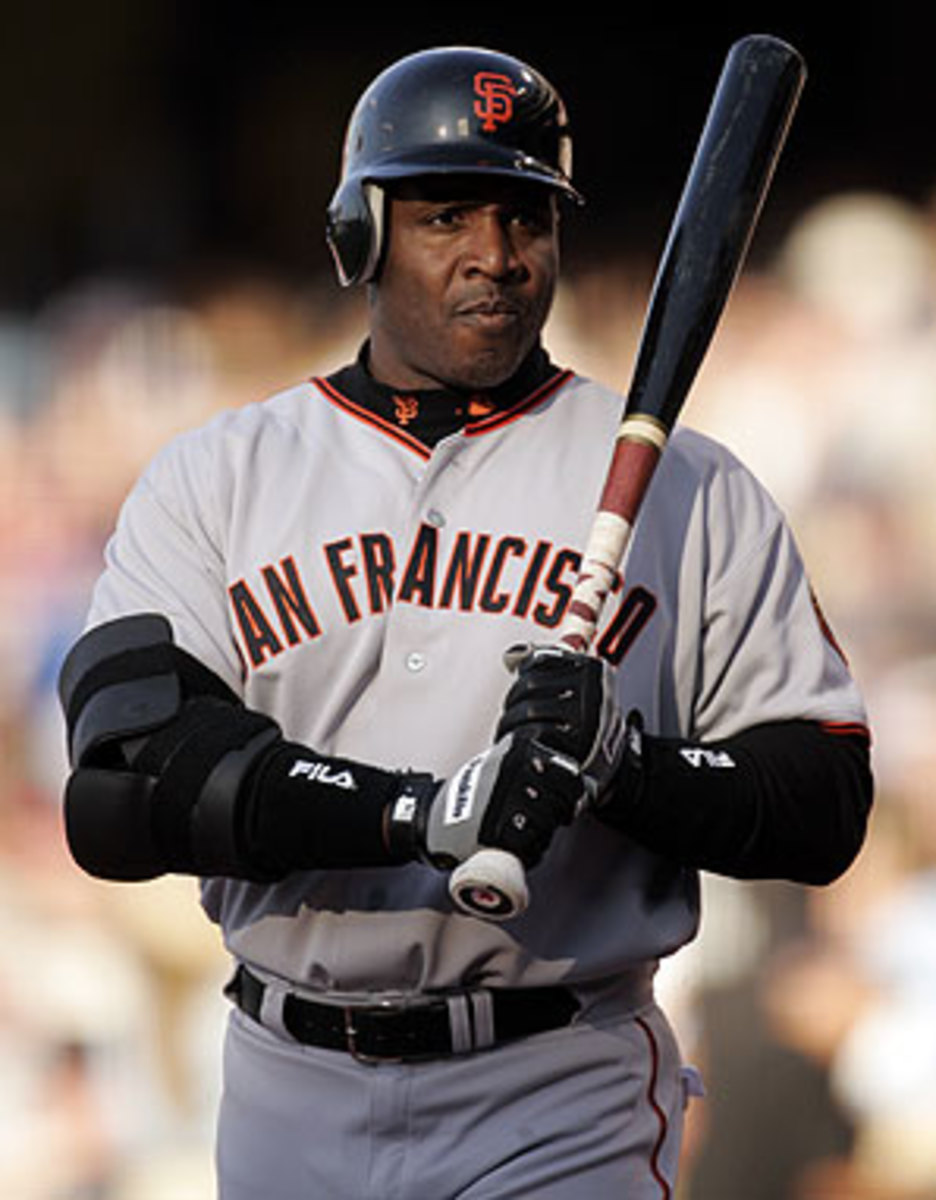

As for the narrative, Burns and company hit all the right notes, presenting their story in a sensitive and balanced fashion. Steroids is a major focus, of course, as are the continuing labor wars, the prominence of Latin stars, Joe Torre's Yankees and the 2004 Red Sox. Cal Ripken, Sammy Sosa, Mark McGwire, Ken Griffey Jr. and Ichiro are all featured players, while Barry Bonds plays the central role.

Some familiar faces like George Will, Dan Okrent, John Thorn, Doris Kearns Goodwin and Bob Costas return from the original series. Tom Boswell might have even more airtime in The Tenth Inning than he did the first time around and he's excellent. Billy Crystal is not here this time but Joe Torre is, and there are also winning contributions from journalists Marcos Breton, Verducci and Bryant, as well as cameos by Chris Rock, Felipe Alou and Omar Vizquel. Jon Miller is funny in a few spots, though his riff on VORP was goofy -- not hostile or unfunny,just goofy (it would have been nice to hear Michael Lewis or Malcolm Gladwell or Bill James here).

RELATED: Verducci: "Tenth" represents an era of sea change

Nobody could ever replace Buck O'Neil, of course, and the first episode is dedicated to O'Neil's memory. Mike Barnicle comes close as the long-suffering Red Sox fan. Barnicle's career as a journalist has been filled with controversy, but he's a great interview. Ichiro makes a scintillating appearance, but the emotional standout is Pedro Martinez. We first see Pedro talk about being a homesick young player in the minors, dreaming about being back home with his mother, working in the garden together. Then in a sequence devoted to Martinez's dominant run with the Red Sox in the "Bottom of the Tenth," he talks about his craft like the showman we know him to be.

"First of all I'm confident, and a lot of people misjudge that," says Pedro as Burns cuts to a classic shot of Pedro in the dugout wearing big, gold-rimmed shades and horsing around. "People might say, 'he's cocky,'" Pedro continues in a flat voice. "I'm fearless, intense. Some people might say, 'He's mean.' And sometimes, since I'm so intense, I'll strike you out, keep looking at you." Pedro tilts his head to the right, as if following a hitter back to the dugout. He blinks slowly. "See because baseball has a little bit of psychology in it. If you see a guy frustrated with the change-up, you have to continue to throw a change-up. You can't hit a change-up, I'm sorry. You're gonna see it again."

Social events still play a role -- the home run chase of '98 during the Monica Lewinsky scandal, the 2001 playoffs against the backdrop of 9/11 -- but the formal structure of the original series has changed. The new episodes do not begin with an accounting of the major events of the day. Other than the dedication to O'Neil, Burns doesn't cover any deaths. In earlier episodes, the deaths of Babe Ruth and Ty Cobb were notable events, but there is not a similar sense of completion with the passing of Mickey Mantle, Joe DiMaggio or Ted Williams. Or Curt Flood. A more pronounced tribute to Buck would have been welcome, too.

Fans will enjoy picking through Burns story to find errors and oversights. Chicago fans won't be thrilled to find the 2003 Cubs relegated to a short segment or the '05 White Sox glossed over completely. There could have been more on sabermetrics, and Dan Okrent could have anchored a terrific segment on fantasy baseball. Bud Selig and Scott Boras could have played bigger roles, and the same goes for Alex Rodriguez, who is neglected in favor of Bonds. Where is Chipper Jones and Trevor Hoffman, and what about more of Junior Griffey?

The only way Burns could satisfy us is to make a 50-hour movie. But the real problem with The Tenth Inning may be that it is a contemporary tale and not a historical one. The filmmakers weren't only faced with figuring out which stories to tell, but which pictures and video and music to use when they had more material available than ever before. Perhaps as a result, Burns seems off. The slow-motion pans and fades are abrupt. With a few exceptions, the music cues are stale and uninspired. Worse, they often distract from the story instead of enhancing it. But if the artistry isn't always extraordinary, The Tenth Inning is still a rich, satisfying experience. It may be short of a grand slam; call it a bases-clearing double and let's count our blessings.