How Dr. James Andrews went from sports fan to the sports surgeon

He will be at Bryant-Denny Stadium in Tuscaloosa on Friday afternoon, anxiously walking the sidelines, his penetrating green eyes scanning the field for injuries. He is the only man in the state of Alabama who can say he plays for both the Auburn Tigers and the Alabama Crimson Tide. When someone from either team is slow to rise after the whistle blows, the silver-haired 68-year-old who nearly died of a heart attack five years ago will charge forward, and suddenly the most famous sports doctor in America will be on center stage. Look closely into the crowd and, as the man leans down to tend to the fallen athlete, fingers will point and cameras will flash, because in his home state Dr. James Andrews is about as popular -- and well known -- as the two head coaches that will be pacing opposite sidelines.

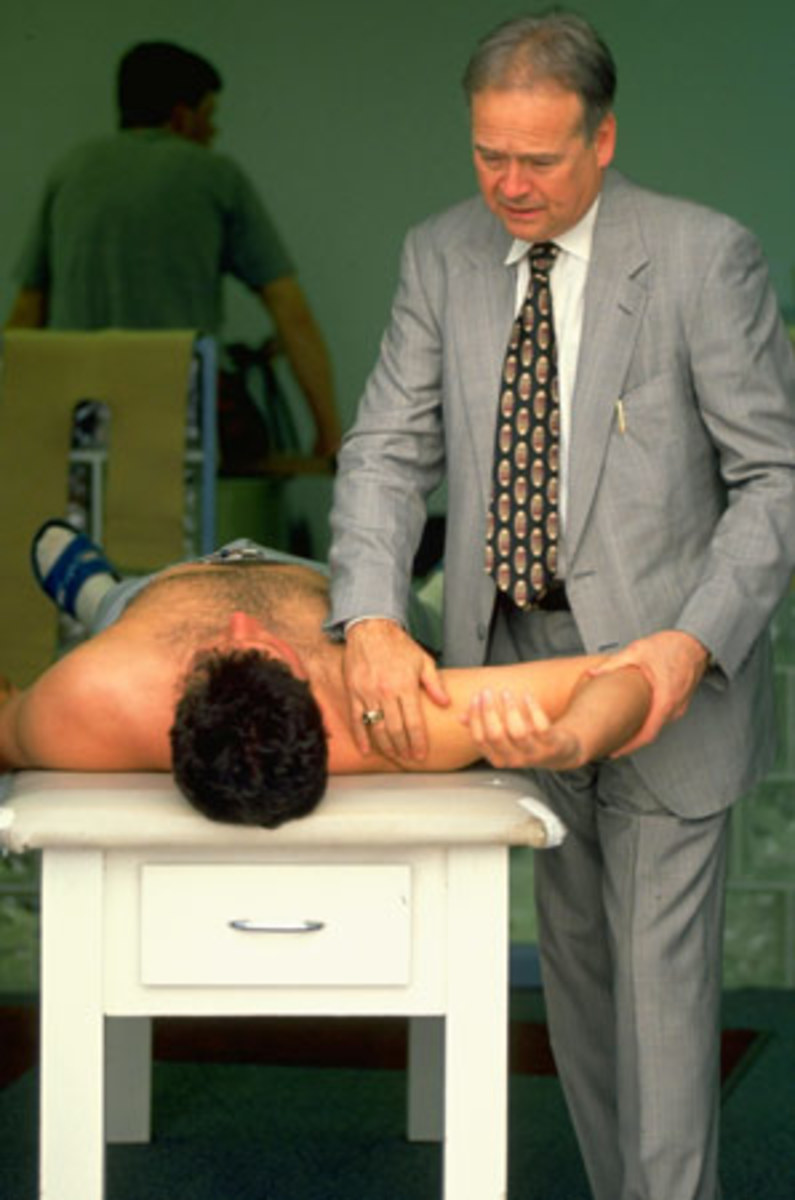

As a team doctor for Alabama Auburn, and the NFL's Washington Redskins, Andrews logs more miles on Saturdays and Sundays each autumn than perhaps any doctor in America -- and that is the slow part of his week. On Monday through Friday, between spending time at the Andrews Sports Medicine and Athletic Center in Birmingham, Ala., and at the Andrews Institute for Orthopedics and Sports Medicine in Pensacola, Fla., Andrews performs as many as 50 surgeries a week, examines as many as 30 X-rays and MRIs that are sent to him each week by team doctors and professional athletes from around the country, and sees as many as 60 patients in the midst of rehabilitation. You think you're busy? Spend a week in the life of Andrews, who has become the sports world's go-to orthopedic surgeon.

So how, exactly, has this happened? How has Andrews, who has performed more than 45,000 surgeries in his career -- mostly on knees, shoulders, and elbows -- become so famous that he's on a first-name basis with nearly half of the starting quarterbacks in the NFL (just last week he consulted with the Vikings' Brett Favre and examined the Lions' Matthew Stafford) and nearly all of the league's head coaches? It's a story that begins, Andrews asserts, very simply.

"You see this," Andrews said on a recent fall morning, holding up his cell phone. "I return calls. Everyone's calls. This morning I had calls in from 10 NFL teams, and I'll get back to all of them today. My whole career I've always tried to be accessible. That's as important to me as anything. If you call me, you know I'll get back to you."

*****

The notes cover the walls at Andrews' clinic in Birmingham that is attached to St. Vincent's hospital:

"Thank you for extending my career. You're the best." -- Zach Thomas

"Thanks for putting me back together." -- Trent Green

"Thanks for everything." -- Donavan McNabb

"My knee is as strong as ever." -- Will Demps

"Thanks for helping me reach my dreams." -- Brodie Croyle

"Thanks to you and your staff for taking me on." -- Daunte Culpepper

The first future Hall of Fame athlete to say thank you to Andrews was Roger Clemens. Indeed, the genesis of Andrews' rise in the world of sports medicine can be traced back to 1986 when Clemens traveled south to meet Andrews. At the time Andrews was a young, sports-crazed orthopedic surgeon in Columbus, Ga. A former pole vaulter at LSU -- as a junior, he won the conference championship with a jump of 15' 1 ½'' -- Andrews inherited his love of sports from his father, Rheuben, who coached football and track in Homer, La., and his interest in medicine from his grandfather James Nolen, who was known as a healer in the woods of rural Louisiana, dispensing ointments and salves to anyone who came to him with a malady. "My dad and grandfather planted the two seeds," says Andrews. "Sports and medicine."

At LSU medical school in New Orleans, Andrews pursued orthopedics, he says, "because that's where the team doctors came from." After graduating, he moved to Columbus, Ga., and in 1973 started practicing with Dr. Jack Hughston, who is known as one of the fathers of modern sports medicine and was Auburn's longtime team doctor.

Some background: Throughout the '60s, '70s, and early '80s most team doctors at the high school, collegiate, and professional level landed their jobs because they were friends with the coaching staff. This, in turn, often compelled the doctors to offer diagnoses that the coaching staff would deem favorable -- one that usually translated into getting the player back onto the field of play as quickly as possible, even if it wasn't in the best interests of the player.

One day in 1986 Andrews received a call from a sports agent searching for a second opinion for an injured client of his. The agent, Randy Hendricks, wanted Clemens to be examined by a doctor who had access to state of the art equipment, and he'd heard about a straight-talking, innovative physician who was treating players on the minor league baseball in the area. Clemens, then in his second year with the Red Sox, was experiencing shoulder pains when he pitched and was losing steam off his fastball after a few innings. So Hendricks sent him to Columbus -- and the world of sports medicine has never been the same.

After examining Clemens, Andrews performed minor -- yet ahead of its time -- arthroscopic surgery and guided Clemens step-by-step through his rehab, teaching the power pitcher a series of simple exercises that would help him maintain the strength of his shoulder. Eight months after going under the knife, Clemens struck out a major-league record 20 batters against the Seattle Mariners. Among those he thanked afterward was Andrews. But Clemens did more than that: He began telling any injured player he came across -- on the Red Sox, on opposing teams, even players from the NFL and other leagues -- that he should go visit that magical doctor in the south who he believed saved his career.

"Word-of-mouth is a powerful thing among athletes," Andrews says. "You could say my life changed after working with Roger."

Soon the biggest stars in sports were coming to see Andrews: Jack Nicklaus, Bo Jackson, Doug Williams, Jimmy Key, Bruce Smith, Charles Barkley, Troy Aikman, Michael Irvin, John Smoltz, Emmitt Smith, Michael Jordan. In the late '80s Andrews left Columbus and started his own practice in Birmingham. How well-known is he in the Magic City today? Recently a college football player walked out of the Birmingham airport and ducked into a cab. His arm was in a sling. "Let me guess," the cab driver said. "I'm taking you to see our friend Dr. Andrews."

The player nodded, and the cab sped toward the Andrews clinic, the wheels of the vehicle rolling along a familiar road to recovery.

*****

He nearly died. That's what the doctors told Andrews on the January 2005 morning when he collapsed in the shower before church. He'd spent the previous night with a Redskins player who had fractured his elbow against the Buccaneers, and Andrews didn't walk out of the Tampa Bay hospital until 4.a.m He then flew on his private jet back to Birmingham, but didn't crawl into bed until the sun was rising. Some two hours later, he was in the shower when, suddenly, he found it hard to breathe.

He fell to the ground. He crawled out of the shower and, struggling for air, told his wife, Jenelle, to call an ambulance. And then, in stroke of luck that surely saved his life, the heart team at St. Vincent's hospital in Birmingham happened to be finishing a procedure -- a rarity for a Sunday morning -- when Andrews arrived. They operated, installing a stent, and then issued an order: No working.

A few days later, Andrews was lying in his hospital bed watching the AFC wild-card game between the Bengals and Steelers. Early in the first quarter he saw Kimo von Oelhoffen of the Steelers roll into the left knee of Bengals quarterback Carson Palmer. It was a gruesome-looking injury. Minutes after it occurred, Andrews' cell phone, which he had smuggled into his room, suddenly rang.

It was Palmer, who was in the Bengals locker room, his knee wrapped in ice. He wanted to know if he could come to Birmingham.

"Well," replied Andrews, "you should know I just had a heart attack."

Palmer never made the trip to Birmingham -- and could that be why he's never been the same player since? -- because Andrews was in no shape to operate. (He's now fully recovered after undergoing quadruple-bypass surgery.) His wife soon took Andrews' cell phone away, but the incident underscored what, at the core, makes Andrews one of a kind: The man, no matter the circumstance, is always on call.

*****

It's a cool autumn afternoon in Birmingham, and the cell phone rarely stops ringing. Andrews, fresh off performing five surgeries this morning -- including an ACL procedure on a 2010 NFL first round draft pick and Tommy John elbow surgery on a Division II linebacker -- is relaxing in a private suite at the Andrews Sports Medicine and Athletic Center. First the Raiders call wanting Andrews' opinion on the X-rays of five players the team sent him this morning; then the Eagles ring; then the Falcons; then the Bills; then an agent; then another agent; then the Portland Trailblazers; then the Rams.

"I don't believe in e-mail," Andrews says as he punches digits into his phone. "I've got to talk to people. Direct communication is the best. I learned that a long time ago."

On this afternoon at the Andrews clinic several NFL players are rehabbing from surgery, including Tennessee Titans cornerback Rod Hood, who tore his ACL in mid-June and was operated on by Andrews. "His reputation among players in the league is second to none," says Hood of Andrews. Hood has been living in Birmingham for three months while strengthening his knee under Andrews' care.

"The thing about Dr. Andrews is that he befriends you, talks to you about your family, your dreams," Hood says. "You can tell he cares and loves sports. So many doctors just aren't like that, even ones that work on NFL players. When Dr. Andrews tells you you're going to be fine, you believe him. And I think that's half of the battle, just believing that you'll get back to where you were."

Not far from Hood is Kiva Thomas, who is touring the rehab room. She plays on professional women's football team in Indianapolis -- the Indiana Speed -- and recently tore the ACL in her right knee. Tomorrow Andrews will repair all that was shredded. "I'm a nobody in the sports world, and I still can't believe that Dr. Andrews is seeing me," says Thomas. "It's so comforting to know that I'm in the hands of the best of the best."

She pauses, looks out a window and then fastens her gaze on her wounded knee. "This might sound weird," she says, a smile slowly rippling across her face. "But it's like it's an honor to be here. It's an honor to have Dr. James Andrews operate on me. I feel so lucky."

Thomas is far from the first to utter those words.